British nationality law

British nationality law details the conditions in which a person holds a type of British nationality. There are six different classes of British nationality, each with varying degrees of civil and political rights, due to the United Kingdom's historical status as a colonial empire.

| British citizenship and nationality law |

|---|

|

| Introduction |

| Nationality classes |

|

| See also |

| Relevant legislation |

History

English law and Scots law have always distinguished between the Monarch's subjects and aliens, but British nationality law was uncodified until the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914 codified existing common law and statute, with a few minor changes.

Some thought the single Imperial status of "British subject" was becoming increasingly inadequate to deal with a Commonwealth of independent member states. In 1948, the Commonwealth Heads of Government agreed that each member would adopt a national citizenship (Canada had already done so), but that the existing status of British subject would continue as a common status held by all Commonwealth citizens.

The British Nationality Act 1948 marked the first time that married British women gained independent nationality, regardless of the citizenship of their spouses.[1] It established the status of Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKC), the national citizenship of the United Kingdom and colonies on 1 January 1949. Until the early 1960s there was little difference, if any, in UK law between the rights of CUKCs and other British subjects, all of whom had the right at any time to enter, live and work in the UK.

Independence acts, passed when the remaining colonies were granted independence, contained nationality provisions. In general, these provisions withdrew CUKC status from anyone who became a citizen of the newly independent country, unless the person had a connection with the UK or a remaining colony (e.g. through birth in the UK). Exceptions were sometimes made in cases where the colonies did not become independent (notable cases include the Crown Colony of Penang and the Crown Colony of Malacca, which were made part of the Federation of Malaya in 1957; CUKC status was not withdrawn from CUKCs from Penang and Malacca even though they automatically acquired Malayan citizenship at the time of independence).

Between 1962 and 1971, as a result of fears about increasing immigration by Commonwealth citizens, the UK gradually tightened controls on immigration by British subjects from other parts of the Commonwealth, which included CUKCs without familial or residential ties to the UK. The Immigration Act 1971 introduced the concept of patriality, by which only British subjects (i.e. CUKCs and Commonwealth citizens) with sufficiently strong links to the British Islands (e.g. being born in the islands or having a parent or a grandparent who was born there) had right of abode, meaning they were exempt from immigration control and had the right to enter, live and work in the islands. The act, therefore, had de facto created two types of CUKCs: those with right of abode in the UK, and those without right of abode in the UK (who might or might not have right of abode in a Crown colony or another country). Despite differences in immigration status being created, there was no de jure difference between the two in a nationality context, as the 1948 Act still specified one tier of citizenship throughout the UK and its colonies. This changed in 1983, when the 1948 Act was replaced by a multi-tier nationality system.

The current principal British nationality law in force, since 1 January 1983, is the British Nationality Act 1981, which established the system of multiple categories of British nationality. To date, six tiers were created: British citizens, British Overseas Territories citizens, British Overseas citizens, British Nationals (Overseas), British subjects, and British protected persons. Only British citizens and certain Commonwealth citizens have the automatic right of abode in the UK, with the latter holding residual rights they had prior to 1983.

Aside from different categories of a nationality, the 1981 Act also ceased to recognise Commonwealth citizens as British subjects. There remain only two categories of people who are still British subjects: those (formerly known as British subjects without citizenship) who acquired British nationality through a connection with former British India, and those connected with the Republic of Ireland before 1949 who have made a declaration to retain British nationality. British subjects connected with former British India lose British nationality if they acquire another citizenship.

In spite of the fact that the 1981 Act repealed most of the provisions of the 1948 Act and the nationality clauses in subsequent independence acts, the acquisition of new categories of British nationality created by the 1981 Act was often dependent on nationality status prior to 1 January 1983 (the date the 1981 Act entered into force), so many of the provisions of the 1948 Act and subsequent independence acts are still relevant. Not taking this into account might lead to the erroneous conclusion, for example, that the 1981 Act's repeal of the nationality clauses in the Kenya Independence Act of 1963 restored British nationality to those who lost their CUKC status as a result of Kenya's independence in 1963. This is one of the reasons for the complexity of British nationality law; in complicated cases, determining British nationality status requires an examination of several nationality acts in their original form.

Classes of British nationality

As of August 2019, there are six classes of British nationality.[2]

| Category | Active | British passport |

Consular assistance from UK diplomatic posts |

Exempt from UK immigration control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Citizen | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ |

| British Overseas Territories citizen | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️(Gibraltar) |

| ❌(other territories) | ||||

| British Overseas citizen | ❌ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ❌ |

| British subject | ❌ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️(with right of abode) |

| ❌(without right of abode) | ||||

| British National (Overseas) | ❌ | ✔️ | ❌(Chinese dual nationals in China, including Hong Kong & Macau) | ❌ |

| ✔️(other nationalities and/or other places) | ||||

| British protected person | ❌ | ✔️ | ✔️ | ❌ |

Active categories

The following two classes of British nationality are "active", meaning that they can be acquired by any eligible person at birth or by naturalisation or registration.

- British citizen

- Persons who are British citizens usually hold this status through a connection with the United Kingdom, Channel Islands and Isle of Man ("United Kingdom and Islands"); the Falkland Islands; or, since 2002, one of the remaining British Overseas Territories (BOTs), except Akrotiri and Dhekelia.[3] Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKCs) who possessed right of abode under the Immigration Act 1971 through a connection with the UK and Islands generally became British citizens on 1 January 1983. This status was also retroactively extended to British Dependent Territories citizens with a connection to the Falkland Islands on 28 March 1983, while the remaining British Dependent Territories citizens who were not solely connected with Akrotiri and Dhekelia acquired the status on 21 May 2002.

- British citizenship is the most common type of British nationality, and the only one that bestows automatic right of abode in the UK.

- Other rights can vary depending on how the British citizenship was acquired. In particular, there are restrictions for "British citizens by descent" when transmitting British citizenship to children born outside the UK. These restrictions do not apply to "British citizens otherwise than by descent".

- British Overseas Territories citizen (formerly British Dependent Territories citizen) (BOTC)

- BOTC (formerly BDTC) is the form of British nationality held through connection with any British Overseas Territory (BOT). It is possible to hold BOTC and British citizenship simultaneously. Nearly all BOTCs are now also British citizens as a result of the British Overseas Territories Act 2002.

Residual categories

The four residual categories are expected to lapse with the passage of time. They can be passed to children only in exceptional circumstances, e.g., if the child would otherwise be stateless. There is consequently little provision for the acquisition of these classes of nationality by people who do not already have them. To reduce de facto statelessness, most are allowed to be registered as British citizens as long as they hold no other citizenship or nationality.

- British Overseas citizen (BOC)

- In general, most BOCs are CUKCs who did not qualify for British citizenship or British Dependent Territories citizenship. Most derived their status as CUKCs from former colonies, such as Malaysia and Kenya, because of quirks and exceptions in the law that resulted in their retaining CUKC status in spite of the independence of their colonies. This is fairly uncommon: most CUKCs (including those from Malaysia and Kenya) lost their CUKC status upon independence.

- In 1997, BDTCs with a connection to Hong Kong became BOCs if they did not register as British Nationals (Overseas) and would have become stateless after the withdrawal of BDTC status from Hong Kong residents.

- British subject

- British subjects (as defined in the 1981 Act) are British subjects who were not CUKCs or citizens of any other Commonwealth country. Most derived their status as British subjects from British India or the Republic of Ireland as they existed before 1949.

- British National (Overseas) (BN(O))

- The status of BN(O) was created by the Hong Kong Act 1985 and the British Nationality (Hong Kong) Order 1986. BN(O)s are BDTCs with a connection to Hong Kong who applied for registration as BN(O)s before the handover of Hong Kong to the People's Republic of China. It was announced on the 1 July 2020 that, following the imposition of the national security law in Hong Kong, the UK would grant BN(O) passport holders, and those who would have been eligible but did not apply, would be granted limited leave to remain in the UK for 5 years. After which, they can apply for settled status and citizenship a year thereafter.[4]

- British protected person (BPP)

- BPPs derive from parts of the British Empire that were protectorates or protected states with nominally independent rulers under the "protection" of the British Crown, not officially part of the Crown's dominions. The status of BPP is sui generis – BPPs are not Commonwealth citizens ("British subjects", in the old sense) and were not traditionally considered British nationals, but are not aliens either.

Relationship with right of abode

Only the status of British citizen carries with it the right of abode in a certain country or territory (in this case, the UK).

In practice, BOTCs (except those associated with the Sovereign bases in Cyprus) were granted full British citizenship in 2002; BN(O)s have right of abode or right to land in Hong Kong (note: not conferred by the status itself, but by the Immigration Ordinance of Hong Kong) and are eligible for registration as British citizens if they hold no other nationality under the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009; BSs and BPPs lose their statuses upon acquiring another nationality (except BSs connected with the Republic of Ireland) and so should be eligible for registration as British citizens under the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

British Overseas citizens are unique in that their nationality status is not associated with a right of residence, and only certain types of BOCs are eligible to be registered as British citizens under the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Acquisition of British citizenship

British Citizenship can be acquired in the following ways:

- lex soli: By birth in the UK or a qualified British Overseas Territory to a parent who is a British citizen at the time of the birth, or to a parent who is settled in the UK or that Overseas Territory

- lex sanguinis: By birth abroad, which constitutes "by descent" if one of the parents is a British citizen otherwise than by descent (for example by birth, adoption, registration or naturalisation in the UK). British citizenship by descent is only transferable to one generation down from the parent who is a British citizen otherwise than by descent, if the child is born abroad.

- By naturalisation

- By registration

- By adoption

For nationality purposes, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man are generally treated as if they were part of the UK.[5]

Information about British citizenship and other kinds of British nationality is available from Her Majesty's Government.[6] Information is also available on provisions for reducing statelessness.[7]

Persons acquiring citizenship by method (2) are called British citizens by descent; those acquiring citizenship by methods (1), (3) or (5) are called British citizens otherwise than by descent. British citizens by registration, method (4), may be either, depending on the circumstances. Only citizens otherwise than by descent can pass on their citizenship to their children born outside the UK or a British Overseas Territory automatically; British citizens by descent can pass on citizenship to their non-UK born children only by meeting certain UK residence requirements and registering them before the age of 18.

British citizenship by birth in the United Kingdom or a qualified British Overseas Territory

From 1 January 1983, a child born in the UK or the Falkland Islands[8] to a parent who is a British citizen or "settled" in the UK or the Falkland Islands is automatically a British citizen by birth. This provision is extended to children born to such parents in any remaining British Overseas Territory other than Akrotiri and Dhekelia after 21 May 2002. Since 13 January 2010, a child born to a parent who is a member of the British Armed Forces at the time of birth also automatically acquires British citizenship if he or she was born in the UK or a qualified British Overseas Territory.

- Only one parent needs to meet this requirement.

- "Settled" status usually means the parent is resident in the UK or a British Overseas Territory and has the right of abode (or similar status), or holds Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR), or is a citizen of an EU/EEA Member State and has permanent residence, or is otherwise unrestricted by immigration laws to remain in the UK or that Overseas Territory.[9] Irish citizens in the UK are deemed settled for this purpose.

- To qualify under the armed forces provision, the parent must be a member of the armed forces at the time of the child's birth.

- Special rules exist for cases where a parent of a child is a citizen of a European Union or European Economic Area Member State, or Switzerland. The law in this respect was changed on 2 October 2000 and 30 April 2006. See below for details.

- For children born before 1 July 2006, if only the father meets this requirement, the parents must be married. Marriage subsequent to the birth is normally enough to confer British citizenship from that point.

- Where the father is not married to the mother, the Home Office usually registers the child as British provided an application is made and the child would have been British otherwise. The child must be under 18 on the date of application.

- Where, after the child's birth, a parent subsequently acquires British citizenship or "settled" status, the child can be registered as a British citizen using Form MN1 provided he/she is aged under 18.[10][11]

- If the child lives in the UK until the age of 10, there is a lifetime entitlement to register as a British citizen using Form T. The immigration status of the child and his/her parents is irrelevant. During each of the first 10 years of the child's life, he/she must not have spent over 90 days outside the UK (unless there were "special circumstances"). The applicant must be of good character at the time the application is made.[12][11]

- A child born in the United Kingdom who is and has always been stateless may also qualify on the basis of a period of 5 years' residence, rather than 10, using Form S3.[13]

- Special provisions may apply for the child to acquire British citizenship if a parent is a British Overseas citizen or British subject, or if the child is stateless.

Even if a child is born in the UK on or after 1 January 1983 but does not acquire British citizenship at birth, the child is considered a lawful resident in the UK and is not required to apply for leave to remain.[14][15] The child, however, is subject to immigration control and the child's parent(s) can choose to apply to regularise the child's immigration status through the granting of leave to remain (for the same period as that held by the parent(s)). If the child leaves the UK, he/she must hold leave to enter or remain in order to return to the UK.[16]

Before 1983

Between 1949 and 1982, birth in the UK or a Crown Colony was sufficient in itself to confer the status of Citizen of United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKC), regardless of the parents' status, although only CUKCs with a connection to the UK (i.e. birth in the UK or has a UK-born parent or grandparent) had right of abode in the UK after 1971 and would eventually become British citizens in 1983. CUKCs without a connection to the UK became either British Overseas Territories citizens or British Overseas citizens in 1983, depending on whether they had a connection to another BOT.

The only exception to this rule were children of diplomats and enemy aliens. This exception did not apply to most visiting forces, so, in general, children born in the UK before 1983 to visiting military personnel (e.g. US forces stationed in the UK) were CUKCs connected to the UK and would become British citizens in 1983, albeit as a second nationality.

British citizenship by descent

"British citizenship by descent" is the category for children born outside the UK or an Overseas Territory to a British citizen. Rules for acquiring British citizenship by descent depend on when the person was born.

From 1983

A child born outside the UK, Gibraltar or the Falkland Islands on or after 1 January 1983 (or outside another British Overseas Territory on or after 21 May 2002) automatically acquires British citizenship by descent if either parent is a British citizen otherwise than by descent at the time of the child's birth.

- At least one parent must be a British citizen otherwise than by descent.

- As a general rule, an unmarried father cannot pass on British citizenship automatically in the case of a child born before 1 July 2006. If the parents marry subsequent to the birth, the child normally becomes a British citizen at that point if legitimated by the marriage and the father was eligible to pass on British citizenship. If the unmarried British father was residing in a country that treated (at the date of birth of the child born before 1 July 2006) a child born to unmarried parents in the same way as a child born to married parents, then the father passed on British citizenship automatically to his child, even though the child was born before 1 July 2006 to unmarried parents.[17] Such countries are listed in the UK Home Office Immigration and Passport Services publication "Legitimation and Domicile".[18]

- Where the parent is a British citizen by descent, additional requirements apply. In the most common scenario, the parent is normally expected to have lived in the UK for three consecutive years and apply to register the child as a British citizen while the child is a minor (clause 43, Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009, effective from 13 January 2010). Prior to this date, the age limit was 12 months.

- Before 21 May 2002, all British Overseas Territories except two were treated as 'overseas' for nationality purposes. The exceptions were Gibraltar, where residents are eligible to register as British citizens under section 5 of the British Nationality Act 1981; and the Falkland Islands, granted British citizenship following the Falklands War under the British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act 1983. Hence, children born to such parents on a British Overseas Territory other than those listed above acquired British citizenship by descent if they were born prior to 21 May 2002, while children born on or after that day on a British Overseas Territory (other than Akrotiri and Dhekelia) acquired British citizenship otherwise than by descent as UK-born children.

- Children born overseas to parents on Crown Service are normally granted British citizenship otherwise than by descent, so their status is the same as it would have been had they been born in the UK.

- In exceptional cases, the Home Secretary may register a child of parents who are British by descent as a British citizen under discretionary provisions, for example if the child is stateless, or a second or subsequent generation born abroad into a British citizen family with strong links with the UK, or in 'compassionate circumstances'.[19]

Before 1983

Before 1983, as a general rule CUKC status was transmitted automatically only for one generation, with registration in infancy possible for subsequent generations. Transmission was from the father only, and only if the parents were married. (See History of British nationality law.)

In 1979 the Home Office had begun to take quiet steps to address this gender discrimination by allowing British citizen mothers to register children born abroad at the local British consulate within one year of birth, just as British citizen fathers could.[20][21] However, the change was without great publicity and was largely unnoticed, and in 2002, Parliament formalized the approach in law, by enacting amendments to the British Nationality Act 1981 allowing children who had been covered by the 1979 procedural change (because they were under 18 years old at that time) to register themselves at any point later in life.[20][21] The class of eligible registrants was later expanded in 2009, and was upheld by a 2018 UK Supreme Court ruling.[20][21]

Several laws also accorded a right of registration to children born of unmarried British citizen fathers.

Children ineligible for British citizenship at birth

Children born outside the UK before 1 January 1983 to a CUKC mother who became a British citizen on 1 January 1983 and a foreign father are not British citizens by birth, and neither are children born between 1 January 1983 to 1 July 2006 to a British citizen father and a foreign mother out of wedlock.

In the face of various concerns over gender equality, human rights, and treaty obligations, Parliament moved to act on these situations.[21]

The Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 inserted a section 4C into the British Nationality Act 1981 allowing for registration as a British citizen of any person born between 7 February 1961 and 1 January 1983 who would have become a CUKC if the British Nationality Act 1948 had provided for mothers to transmit citizenship in the same way that fathers could.[22] The Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 then expanded the earliest date of birth covered from 1961 to 1 January 1949, and elaborated in "a dense and at times impenetrable piece of drafting"[23][21] on the section's approach, while also covering numerous additional and less common situations, and adding a good character requirement.[24]

Registration through this method is performed with Form UKM. After approval, the registrant must attend a citizenship ceremony. Since 2010, there is no longer an application fee (of £540). Applicants do however still have to pay £80 for the citizenship ceremony.[25]

From 6 April 2015, a child born out of wedlock before 1 July 2006 to a British father is entitled to register as a British citizen by descent under the Immigration Act 2014 using form UKF.[26] Such child must also meet character requirements, pay relevant processing fees and attend a citizenship ceremony.[27] However, if the applicant has a claim to register as a British citizen under other clauses of the British Nationality Act 1981, or has already acquired British citizenship after being legitimised, the application will be refused.

Alternatively, if already resident in the UK, these children may seek naturalisation as a British citizen, which gives transmissible British citizenship otherwise than by descent.

For descendants of pre-1922 Irish emigrants

Under section 5 of the Ireland Act 1949, a person who was born in the territory of the future Republic of Ireland as a British subject, but who did not receive Irish citizenship under the Ireland Act's interpretation of either the 1922 Irish constitution or the 1935 Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act (because he or she was no longer domiciled in the Republic on the day the constitution came into force and was not permanently resident there on the day of the 1935 law's enactment and was not otherwise registered as an Irish citizen) was deemed to be a Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies.[28][29]

As such, many of those individuals and some of the descendants in the Irish diaspora of an Irish person who left Ireland before 1922 (and who was also not resident in 1935) may both be registrable for Irish citizenship and be a British citizen,[30] through either:

- birth to the first generation emigrant,

- registration of later generation births by the married citizen father at the local British consulate within one year of birth, prior to the British Nationality Act (BNA) 1981 taking effect,

- by registration, at any time in life, with Form UKF, of birth to an unwed citizen father, or

- by registration, at any time in life, with Form UKM, of birth to a citizen mother between the BNA 1948 and the BNA 1981 effective dates, under the UK Supreme Court's 2018 Romein principle.[31][32]

In some cases, British citizenship may be available to these descendants in the Irish diaspora when Irish citizenship registration is not, as in instances of failure of past generations to timely register in a local Irish consulate's Foreign Births Register before the 1986 changes to Irish nationality law and before births of later generations.[30]

British citizenship by adoption

A child adopted by a British citizen acquires British citizenship automatically only if:

- the adoption order is made by a court in the UK, Channel Islands, Isle of Man or Falkland Islands on or after 1 January 1983, or in another British Overseas Territory on or after 21 May 2002; or

- it is a Convention adoption under the 1993 Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption effected on or after 1 June 2003 and the adopters are habitually resident in the UK on that date.

In both cases, at least one adoptive parent must be a British citizen on the date of the adoption.

The requirements are different for persons adopted before 1983.

In all other cases, an application for registration of the child as a British citizen must be made before the child is 18. Usually this is granted provided the Secretary of State accepts the adoption is bona fide and the child would have been a British citizen if the natural child of the adopters. Usually the adoption must have taken place under the law of a 'designated country' (most developed nations along with some others are 'designated' for this purpose) and be recognised in the UK. This is the standard method for children adopted by British citizens permanently resident overseas to acquire British citizenship.

The cancellation or annulment of an adoption order does not cause loss of British citizenship acquired by that adoption.

British children adopted by non-British nationals do not lose British nationality, even if they acquire a foreign nationality as a result of the adoption.

Any person who obtains British nationality by this method is British otherwise than by descent, which means they have the same status as those born or naturalised in the UK and can pass on British nationality to their children.

British citizenship by naturalisation

Naturalisation as a British citizen is at the discretion of the Home Secretary, who may grant British citizenship to anyone they "think fit".[33] Although the Home Office sets down official requirements for naturalisation they may waive any of them, or may refuse citizenship to a person even if they meet all of the requirements.[34] However, applications for naturalisation are normally granted if the requirements are met.

Requirements for the applicants

The requirements for naturalisation as a British citizen depend on whether or not one is the spouse or civil partner of a British citizen.

For those married to or in a civil partnership with a British citizen, the applicant must:

- Have held indefinite leave to remain in the UK (or an "equivalent" for this purpose, such as the right of abode, Irish citizenship, or permanent residency as a citizen of an EU/EEA country or a family member of one) at the time they apply for naturalisation. As of 12 November 2015, EEA nationals are explicitly required to obtain a proof of permanent residency in the UK (in the form of permanent residency certificate) if they are to become a British citizen by naturalisation[35] Proof of permanent residence is obtained by completing form EEA (PR) for Home Office approval.[36]

- Have lived legally in the UK for three years

- Be of "good character", as deemed by the Home Office (in practice the Home Office carries out checks with the police and with other Government departments)

- Show sufficient knowledge of life in the UK, either by passing the Life in the United Kingdom test or by attending combined English language and citizenship classes. Proof of this must be supplied with one's application for naturalisation. Exemption from this and the language requirement (see below) is normally granted for those aged 65 or over, and may be granted to those aged between 60 and 65. Note that this is required for permanent residency, not just for citizenship, and married partners may be deported if they are unable to pass the test. The test has attracted controversy for being "like a bad pub quiz"[37] and the subject of a critical, comprehensive report by Thom Brooks.[38]

- Meet specified English, Welsh or Scottish Gaelic language competence standards. Those who pass the Life in the UK test are deemed to meet English language requirements

For those not married to or in a civil partnership with a British citizen, the requirements are:[39][40]

- Five years' legal residence in the UK

- Indefinite leave to remain or "equivalent" for this purpose (see above) must have been held for 12 months

- the applicant must intend to continue to live in the UK or work overseas for the UK government or a British corporation or association

- the same "good character" standards apply as for those married to British citizens

- the same language and knowledge of life in the UK standards apply as for those married to British citizens

Differences of requirements, if applying from outside the UK

Those applying for British citizenship in the Channel Islands and Isle of Man (where the application is mainly based on residence in the Crown Dependencies rather than the UK) do not have to sit the Life in the UK Test. In the Isle of Man, there is a Life in the Isle of Man Test, consisting of certain questions taken from the Life in the UK Test syllabus and certain questions taken from a separate syllabus relating to matters specific to the Isle of Man. In due course it is expected that Regulations will be introduced to that effect in the Channel Islands. The provisions for proving knowledge of English, Welsh or Scottish Gaelic remain unchanged until that date for applicants in the Crown Dependencies. In the rare cases where an applicant is able to apply for naturalisation from outside the United Kingdom, a paper version of the Life in the UK Test may be available at a British diplomatic mission.[41]

Referees

The applicant for naturalisation as a British citizen must provide two referees. One referee should be a professional person, who can be of any nationality. The other referee must normally have a British passport and be either a professional person or more than 25 years old.[42] The official list of persons, who are considered as accepted professional referees, is very limited, but many other professions are usually accepted too.[43][44]

Waiting times

As of 11 February 2009, wait times for naturalisation applications were reportedly up to 6 months.[45] The UK Border Agency stated that this was occurring because of the widespread changes proposed to the immigration laws expected to take effect in late 2009.[46]

Fees

Fees for naturalisation (including Citizenship ceremony fee) have been rising steadily faster than inflation;

- In 2013 the fee for a single applicant increased to £874.

- In 2014 the fee for a single applicant increased to £906.

- In 2015 the fee for a single applicant increased to £1005.

- In 2016 the fee for a single applicant increased to £1236.

- In 2017 the fee for a single applicant increased to £1282.

- In 2018 the fee for a single applicant increased to £1330.

Citizens of EEA States and Switzerland

The immigration status for citizens of European Economic Area states and Switzerland has changed since 1983. This is important in terms of eligibility for naturalisation, and whether the UK-born child of such a person is a British citizen.[47]

Before 2 October 2000

In general, before 2 October 2000, any EEA citizen exercising Treaty rights in the United Kingdom was deemed "settled" in the United Kingdom. Hence a child born to that person in the United Kingdom would normally be a British citizen by birth.

2 October 2000 to 29 April 2006

The Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations[48] provided that with only a few exceptions, citizens of EU and European Economic Area states were not generally considered "settled" in the UK unless they applied for and obtained permanent residency. This is relevant in terms of eligibility to apply for naturalisation or obtaining British citizenship for UK born children (born on or after 2 October 2000).

30 April 2006 to 31 December 2020

On 30 April 2006, the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2006 came into force, with citizens of EEA states and Switzerland automatically acquiring permanent residence after 5 years' residence in the UK exercising Treaty rights.

Children born in the UK to EEA/Swiss parents are normally British citizens automatically if at least one parent has been exercising Treaty rights for five years. If the parents have lived in the UK for less than five years when the child is born, the child may be registered as British under section 1(3) of the British Nationality Act once the parents complete five years' residence.

Children born between 2 October 2000 and 29 April 2006 may be registered as British citizens as soon as one parent has completed five years' residence exercising Treaty rights in the UK.

2021 onwards

Special immigration rights for citizens of the EU, EEA and Switzerland have been abolished starting 1 January 2021 by an Act of Parliament dated 18 May 2020 as part of Brexit. The act doesn't detail the new immigration criteria for those people.[49]

Irish citizens

Because of section 2(1) of the Ireland Act 1949 (which states that the Republic of Ireland would not be treated as a foreign country for the purposes of British law), Irish citizens are exempt from these restrictions and are normally treated as "settled" in the UK immediately upon taking up residence.[50] In March 2020, the British government published a draft law that protects Irish citizens’ right to work and live in the UK following Brexit. The draft legislation says: ‘An Irish citizen does not require leave to enter or remain in the United Kingdom.’[51]

Swiss citizens

From 1 June 2002, citizens of Switzerland are accorded EEA rights in the UK.

Citizens of Greece, Spain and Portugal

Greek citizens did not acquire full Treaty rights in the UK until 1 January 1988[52] and citizens of Spain and Portugal did not acquire these rights until 1 January 1992.[52]

Ten years rule

Non-British children with an EEA or Swiss parent may be registered as British once the parent becomes "settled" in the UK under the terms of the Immigration Regulations dealing with EEA citizens.

A separate entitlement exists for any such UK-born child registered as British if they live in the UK until age 10, regardless of their or their parent's immigration status.

British citizenship by registration

Registration is a simpler method of acquiring citizenship than naturalisation, but only certain people holding a form of British nationality or having a connection to the UK are eligible. In general, language proficiency and knowledge requirements do not apply to applicants for registration.[53]

BOTCs who acquired their citizenship after 21 May 2002 (except for those connected solely with the Akrotiri and Dhekelia) may request registration under section 4A of the 1981 Act without further conditions other than the good character requirement. Registration under section 4A grants citizenship otherwise than by descent.[54] Those connected with Gibraltar may also elect to apply for registration under section 5 of the 1981 Act which grants citizenship by descent.[54]

British nationals who are not British citizens (other than BOTCs solely connected with Akrotiri and Dhekelia) have an entitlement for registration as British citizens under s4 of the 1981 Act provided the following requirements are met:

- have held indefinite leave to remain or right of abode for more than 12 months

- have resided in the UK for five years or more with no more than 450 days' absence from the UK in the last five years (when absent from the UK, only Crown service for a BOT counts toward the residence period)

- have not been absent from the UK for more than 90 days in the last 12 months immediately before the application

- have not breached any immigration laws in the five-year period immediately before the application

This confers citizenship otherwise than by descent.[54]

However, BOTCs solely connected with Akrotiri and Dhekelia are not eligible for registration and must apply for naturalization instead. Naturalization also grants citizenship otherwise than by descent.

Other cases where British nationals who are eligible to register without residency requirements are:

- British Overseas citizens, British subjects and British protected persons who have no other citizenship or nationality before 4 July 2002 (or, if born after that date, have no other citizenship at birth),[55][56] this confers citizenship by descent[54]

- British Nationals (Overseas) who do not hold any other citizenship or nationality before 19 March 2009 (see Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 regarding the extension of section 4B registration), this also confers citizenship by descent[54]

- Certain British nationals from Hong Kong who meet the requirements of the Hong Kong (War Wives and Widows) Act 1996 (otherwise than by descent)[57] or the British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1997 (otherwise than by descent if applicant was a BDTC otherwise than by descent; by descent for others)[58]

Other cases where non-British nationals may be entitled to registration (either as a matter of law or policy) include:

- Born in the UK or a qualified BOT (otherwise than by descent):

- Where a parent obtains British citizenship or 'settled' status (for example, indefinite leave to remain) after the child is born, provided he/she is under the age of 18[59][10][11]

- Those who lived in the UK until the age of 10[60][12][11]

- Where a parent became a member of the armed forces after the child's birth, if the child was born on or after 13 January 2010[61]

- Those who are stateless (i.e., not entitled to either parents' nationality) if they have resided in the UK for 5 years and the application was made before they turned 22 years of age[62]

- Born outside the UK or a qualified BOT:

- Where a parent was a member of the armed forces at the time of the child's birth and stationed outside the UK or a qualified BOT, if the child was born on or after 13 January 2010 (otherwise than by descent)[63]

- Born before 1 July 2006 to a British citizen father who was not married to the non-British mother at the time of the child's birth (only applies to those who are not subsequently legitimized by their parents' marriage after birth depending on father's domicile),[64][65][66] may confer citizenship by descent or otherwise than by descent depending on whether the child would become a citizen by descent or otherwise than by descent had the parents been married

- Born between 1 January 1949 and 31 December 1982 to a CUKC mother who would have been considered a CUKC by descent under section 5 of the British Nationality Act 1948 if the provision had been gender-neutral, and a non-British father[20]

- Certain children born outside the UK to a British citizen by descent (applicant must be a minor at the time of registration), confers citizenship by descent:

- the British citizen parent has resided for at least 3 years in the UK or a qualified BOT and has a parent who was a British citizen otherwise than by descent (residence requirement is waived when the minor would be otherwise stateless)[67]

- both the British citizen parent and their spouse have resided for 3 years in the UK or a qualified BOT[68]

- A former British citizen who renounced British citizenship and subsequently made an application to resume their British citizenship (by descent if applicant was a British citizen by descent; otherwise than by descent for others)[69]

The Home Secretary can exercise discretion under section 3(1) of the 1981 Act and register any child as a British citizen even if they may not meet the formal criteria.[70] Certain adopted children would also be registered under this provision if their adoptions were not made in accordance with the Hague Convention.[71] Registration under section 3(1) confers citizenship otherwise than by descent if neither parent was a British citizen at the time of registration, or by descent if either parent was a British citizen at that time.[54]

Acquisition of British Overseas Territories citizenship

The British Nationality Act 1981 contains provisions for acquisition and loss of British Dependent Territories citizenship (BDTC) (renamed British Overseas Territories citizenship (BOTC) in 2002) on a similar basis to those for British citizenship. The Home Secretary has delegated his powers to grant BOTC to the Governors of the Overseas Territories. Only in exceptional cases is a person naturalised as a BOTC by the Home Office in the UK.

Acquisition of other categories of British nationality

It is unusual for a person to be able to acquire British Overseas citizenship, British subject or British protected person status. They are not generally transmissible by descent, nor are they open to acquisition by registration, except for certain instances to prevent statelessness. It is also not possible for any person to acquire British National (Overseas) status as the registration period for such status had permanently ended on 31 December 1997.

The Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 granted British Overseas Citizens, British Subjects and British Protected Persons the right to register as British citizens if they have no other citizenship or nationality and have not after 4 July 2002 renounced, voluntarily relinquished or lost through action or inaction any citizenship or nationality. Previously such persons would have not had the right of abode in any country, and would have thus been de facto stateless. Despite strong resistance from senior officials at the Home Office,[72] the then Home Secretary, David Blunkett, said on 3 July 2002 that this would "right a historic wrong" that left stateless tens of thousands of Asian people who had worked closely with British colonial administrations.[73] This provision was extended to British Nationals (Overseas) in 2009.

Persons connected with former British colonies

British Overseas citizenship is generally held by persons connected with former British colonies and who did not lose their British Nationality upon the independence of those colonies.

British Nationals (Overseas) and Hong Kong

After the withdrawal of BDTC status from all BDTCs by virtue of a connection with Hong Kong on 30 June 1997, most of them are now either British Nationals (Overseas) and/or British citizens (with or without nationality of China), or Chinese nationals only. The remaining few became British Overseas citizens.

Before the handover in 1997, former BDTCs from Hong Kong had been able to acquire British citizenship under legislation passed in 1990, 1996 and 1997. In other cases, certain persons may already hold British citizenship as a matter of entitlement or through registration under normal procedures.

Although it is no longer possible to acquire British National (Overseas) status after 31 December 1997, stateless children born to such parents are entitled to British Overseas citizenship and can subsequently apply to register as British citizens under the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Since 2009, BN(O)s without other nationalities or citizenship are able to register as British citizens under the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 as well.

British citizens and BN(O)s who are of full or partial Chinese descent are also Chinese nationals under Chinese law unless they have renounced their Chinese nationality with the Hong Kong SAR Government. As China does not recognise multiple nationality, those persons are considered by China as solely Chinese nationals before and after the handover of Hong Kong and hence are not eligible for consular protection when on Chinese soil. Although holding the same nationality under the Chinese nationality law, Chinese nationals with a connection to Hong Kong or Macau have been categorised differently from Chinese nationals domiciled in Mainland China.

In February 2006, in response to extensive representations made by Lord Avebury and Tameem Ebrahim,[74] British authorities announced that 600 British citizenship applications of ethnic minority children of Indian descent from Hong Kong were wrongly refused.[75] The applications dated from the period July 1997 onwards. Where applicants in such cases confirm that they still wish to receive British citizenship, the decision is reconsidered on request. No additional fee is required in such cases. A template to request reconsideration is available for those who want a prior application reconsidered.[76]

Persons born in the Republic of Ireland

Approximately 800,000 persons born before 1949 and connected with the Republic of Ireland remain entitled to claim British subject status under section 31 of the 1981 Act.

Descendants of the Electress Sophia of Hanover

Eligible descendants from the Electress Sophia of Hanover may hold British Overseas citizenship based on their status as British subjects before 1949. Where such a person acquired a right of abode in the UK before 1983, it is possible for British citizenship to have been acquired. See also History of British nationality law and Sophia Naturalization Act 1705.

Loss of British nationality

Renunciation and resumption of British nationality

All categories of British nationality can be renounced by a declaration made to the Home Secretary. A person ceases to be a British national on the date the Home Secretary registers the declaration of renunciation. If a declaration is registered in the expectation of acquiring another citizenship but one is not acquired within six months of the registration, it does not take effect and the person remains a British national.

Renunciations made to other authorities (such as the general renunciation made as part of the US naturalisation ceremony) are not recognised by the UK. The forms must be sent through the UK Border Agency's citizenship renunciation process.[77] There are provisions for the resumption of British citizenship or British overseas territories citizenship renounced for the purpose of gaining or retaining another citizenship. This can generally only be done once as a matter of entitlement. Further opportunities to resume British citizenship are discretionary.

British subjects, British Overseas citizens and British Nationals (Overseas) cannot resume their British nationality after renunciation.

Automatic loss of British nationality

British subjects (other than British subjects by virtue of a connection with the Republic of Ireland) and British protected persons lose British nationality upon acquiring any other form of nationality.

- These provisions do not apply to British citizens.

- British Overseas Territories citizens (BOTCs) who acquire another nationality do not lose their BOTC status but they may be liable to lose belonger status in their home territory under its immigration laws. Such persons are advised to contact the governor of that territory for information.

- British Overseas citizens (BOCs) do not lose their BOC status upon acquisition of another citizenship, but any entitlement to registration as a British citizen on the grounds of having no other nationality no longer applies after acquiring another citizenship.

Deprivation of British nationality

After the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 came into force British nationals could be deprived of their citizenship if and only if the Secretary of State was satisfied they were responsible for acts seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the United Kingdom or an Overseas Territory.

This was extended under the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006; people with dual nationality who are British nationals can be deprived of their British citizenship if the Secretary of State is satisfied that "deprivation is conducive to the public good",[78] or if nationality was obtained by means of fraud, false representation or concealment of a material fact.[79] There is a right of appeal. This provision has been in force since 16 June 2006 when the Immigration, Nationality and Asylum Act 2006 (Commencement No 1) Order 2006 came into force.[80] Loss of British nationality in this way applies also to dual nationals who are British by birth.[78][81] The Secretary of State may not deprive a person of British nationality, unless obtained by means of fraud, false representation or concealment of a material fact, if they are satisfied that the order would make a person stateless. This provision was modified by the Immigration Act 2014 so as not to require that a third country would actually grant nationality to a person; British nationality can be revoked if "the Secretary of State has reasonable grounds for believing that the person is able, under the law of a country or territory outside the United Kingdom, to become a national of such a country or territory."[82] The powers to strip citizenship were initially very rarely used. Between 2010 and 2015, 33 dual nationals had been deprived of their British citizenship.[83] In the two years to 2013 six people were deprived of citizenship; then in 2013, 18 people were deprived, increasing to 23 in 2014. In 2017, over 40 people had been deprived as of July (at this time increased numbers of British citizens went to join "Islamic State" and then tried to return).[84]

The Home Office does not issue information on these cases and is resistant to answering questions,[78] for example under the Freedom of Information Act 2000.[85] It appears that the government usually waits until the person has left Britain, then sends a warning notice to their British home and signs a deprivation order a day or two later.[78] Appeals are heard at the highly secretive Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC), where the government can submit evidence that cannot be seen or challenged by the appellant.[78]

Home Secretary Sajid Javid said in 2018 that until then deprivation of nationality had been restricted to "terrorists who are a threat to the country", but that he intended to extend it to "those who are convicted of the most grave criminal offences". The acting director of Liberty responded "The home secretary is taking us down a very dangerous road. ... making our criminals someone else’s problem is ... the government washing its hands of its responsibilities ... Banishment belongs in the dark ages."[83]

Multiple nationality and multiple citizenship

As of August 2018, there is no restriction in UK law on a British national simultaneously holding citizenship of other countries; indeed the Good Friday Agreement explicitly recognises the right of qualified residents of Northern Ireland to be British, Irish, or both.

Different rules apply to British protected persons and certain British subjects (that do not apply to British citizens). A person who is a British subject other than by connection with the Republic of Ireland loses that status on acquiring any other nationality or citizenship,[86] and a British protected person ceases to be such on acquiring any other nationality or citizenship. Although British Overseas citizens are not subject to loss of citizenship, British Overseas citizens may lose an entitlement to register as a British citizen under s4B of the 1981 Act if they acquire any other citizenship.

A number of other countries do not allow multiple citizenship. If a person has British nationality and is also a national of a country that does not allow dual nationality, the authorities of that country may regard the person as having lost that nationality or may refuse to recognise the British nationality. British nationals who acquire the nationality of a country that does not allow dual nationality may be required by the other country to renounce British nationality to retain the other citizenship. None of this affects a person's national status under UK law.

Under the international Master Nationality Rule a state may not give diplomatic protection to one of its nationals with dual nationality in a country where the person also holds citizenship.

A British subject who acquired foreign citizenship by naturalisation before 1949 was deemed to have lost his or her British subject status at the time. No specific provisions were made in the 1948 legislation for such former British subjects to acquire or otherwise resume British nationality, and hence such a person would not be a British citizen today. However, women who lost British nationality on marriage to a foreign man before 1949 were deemed to have reacquired British subject status immediately before the coming into force of the 1948 act.

The UK is a signatory to the Convention on the Reduction of Cases of Multiple Nationality and on Military Obligations in Cases of Multiple Nationality (1963 Strasbourg Convention). Chapter 1 requires that persons naturalised by another European member country automatically forfeit their original nationality[87] but the UK ratified only Chapter 2, so the convention does not limit the ability of British citizens to become dual citizens of other European countries.[88]

British citizenship ceremonies

From 1 January 2004, all new applicants for British citizenship by naturalisation or registration aged 18 or over if their application is successful must attend a citizenship ceremony and either make an affirmation or take an oath of allegiance to the monarch, and make a pledge to the UK.

Citizenship ceremonies are normally organised by:

- local councils in England, Scotland, and Wales

- the Northern Ireland Office

- the governments of the Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey

- the Governors of British Overseas Territories

- British consular offices outside the United Kingdom and territories.

Persons from the Republic of Ireland born before 1949 reclaiming British subject status under section 31 of the 1981 Act do not need to attend a citizenship ceremony. If such a person subsequently applies for British citizenship by registration or naturalisation, attendance at a ceremony is required.

For those who applied for British citizenship before 2004:

- the oath of allegiance was administered privately through signing a witnessed form in front of a solicitor or other accredited person

- those who already held British nationality (other than British protected persons) were exempt, as were those citizens of countries with the Queen as Head of State (such as Australia and Canada).

Citizenship of the European Union

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

British nationals who are "United Kingdom nationals for European Union purposes", namely:

- British citizens;

- British subjects with the right of abode; and

- British Overseas Territories citizens connected to Gibraltar

have become citizens of the European Union under European Union law and enjoy rights of free movement and the right to vote in elections for the European Parliament.[89] When in a non-EU country where there is no British embassy, British citizens have the right to get consular protection from the embassy of any other EU country present in that country.[90][91] British citizens can live and work in any country within the EU as a result of the right of free movement and residence granted in Article 21 of the EU Treaty.[92]

By virtue of a special provision in the UK Accession Treaty, British citizens who are connected with the Channel Islands and Isle of Man (i.e. "Channel Islanders and Manxmen") do not have the right to live in other European Union countries (except the Republic of Ireland through the long-established Common Travel Area) unless they have connections through descent or residence in the United Kingdom.

In 2020, with Brexit, United Kingdom nationals have lost their citizenship of the European Union when the UK ceased to be a member state. However the withdrawal agreement maintains some of those rights for some of the United Kingdom nationals. This is dealt with in the Part 2 of the agreement named "CITIZENS' RIGHTS", including a sub-title "Rights and obligations".[93]

Statistics on British Citizenship: 1998 to 2009

The Home Office Research and Statistics Division publishes an annual report with statistics on grants of British citizenship broken down by type and former nationality. Since 2003, the report has also included research on take-up rates for British citizenship.

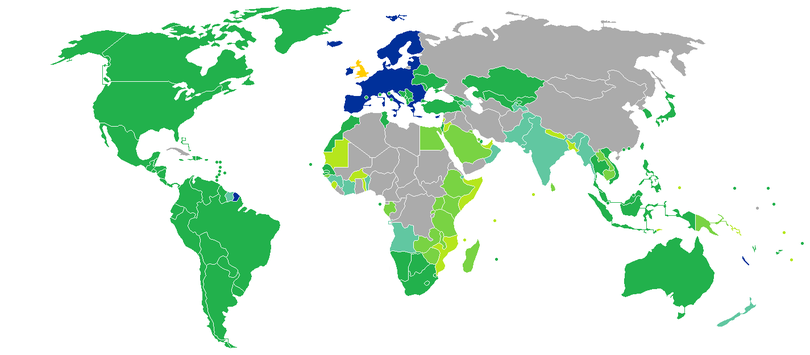

Travel freedom of British citizens

Visa requirements for British citizens are administrative entry restrictions by the authorities of other states placed on citizens of the United Kingdom. In 2017, British citizens had visa-free or visa on arrival access to 173 countries and territories, ranking the British passport 4th in terms of travel freedom (tied with the Austrian, Belgian, Dutch, French, Luxembourgish, Norwegian and Singaporean passports) according to the Henley visa restrictions index.[94] Additionally, the World Tourism Organization also published a report on 15 January 2016 ranking the British passport 1st in the world (tied with Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and Singapore) in terms of travel freedom, with a mobility index of 160 (out of 215 with no visa weighted by 1, visa on arrival weighted by 0.7, eVisa by 0.5, and traditional visa weighted by 0).[95]

Visa requirements for other classes of British nationals such as British Nationals (Overseas), British Overseas Citizens, British Overseas Territories Citizens, British Protected Persons or British Subjects are different.

The British nationality is ranked eighth in Nationality Index (QNI). This index differs from the Visa Restrictions Index, which focuses on external factors including travel freedom. The QNI considers, in addition, to travel freedom on internal factors such as peace & stability, economic strength, and human development as well.[96]

See also

Notes

- Baldwin, M. Page (October 2001). "Subject to Empire: Married Women and the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act". Journal of British Studies. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. 40 (4): 553–554. doi:10.1086/386266. ISSN 0021-9371. JSTOR 3070746. PMID 18161209.

- Lord Goldsmith citizenship review

- British Overseas Territories Act 2002, c.8.

- "Hong Kong: Dominic Raab offers citizenship rights to 2.9 million British nationals". Sky News. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Naturalisation Booklet – The Requirements" (PDF).

- "Types of British nationality". UK Government. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Register as a British Citizen - Stateless People". Gov.uk. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- S2(1) of the British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act 1983

- "Settled" outlined in section 50 of the British Nationality Act 1981 http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1981/61#commentary-c1925606

- British Nationality Act 1981, Section 1(3)

- "Register as a British citizen - GOV.UK".

- British Nationality Act 1981, Section 1(4)

- "UK Government - UK Visas and Immigration: Guidance on registering a stateless person born in the UK or a British overseas territory on or after 1 January 1983 as a British citizen or a British overseas territories citizen using form S3" (PDF). www.gov.uk.

- "Immigration Directorates' Instructions, Chapter 08, Section 4A (Children born in the United Kingdom who are not British citizens)" (PDF). Home Office. November 2009.

- Akinyemi v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2017] EWCA Civ 236

- "Immigration Rules, paragraphs 304-309". Home Office.

- See chapter on "Legitimacy" in UK Border Agency Nationality Instructions, Volume 2, Section 2, paragraphs 1.1, 1.2 and 5.1.2 (second example). http://www.ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk/sitecontent/documents/policyandlaw/nationalityinstructions/nisec2gensec/legitimacy?view=Binary

- "Legitimation and domicile".

- "Home Office Nationality Instructions (Chapter 9: Registration of Minors at Discretion), Section 9.12" (PDF).

- Under the UK Supreme Court's 2018 Romein interpretation of section 4C of the British Nationality Act 1981. Khan, Asad (23 February 2018). "Case Comment: The Advocate General for Scotland v Romein (Scotland) [2018] UKSC 6, Part One". UK Supreme Court Blog. The Advocate General for Scotland (Appellant) v Romein (Respondent) (Scotland) [2018] UKSC 6, [2018] A.C. 585 (8 February 2018), Supreme Court (UK)

- Shelley Elizabeth Romein v The Advocate General for Scotland on behalf of The Secretary of State for the Home Department [2016] CSOH 24, [2017] INLR 76, 2016 SCLR 789, [2016] Imm AR 909 (1 April 2016), Court of Session (Scotland) http://www.bailii.org/scot/cases/ScotCS/2016/[2016]CSIH24.html

- "Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002: Section 13", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 2002 c. 41 (s. 13)

- "U.S. woman wins appeal against 'unlawful' decision to refuse British citizenship". Scottish Legal News Ltd. 4 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "newbook.book" (PDF). Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "Register as a British citizen: Born before 1983 to a British mother". gov.uk. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- "S65 of Immigration Act 2014". Legislation.gov.uk.

- "Register as a British citizen: Born before 1 July 2006 to a British father". Gov.uk.

- R. F. V. Heuston (January 1950). "British Nationality and Irish Citizenship". International Affairs. 26 (1): 77–90. doi:10.2307/3016841. JSTOR 3016841.

- "Ireland Act: Section 5", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1949 c. 41 (s. 5)

- Daly, Mary E. (May 2001). "Irish Nationality and Citizenship since 1922". Irish Historical Studies. Cambridge University Press. 32 (127): 395, 400, 406. doi:10.1017/S0021121400015078. JSTOR 30007221.

- Khan, Asad (23 February 2018). "Case Comment: The Advocate General for Scotland v Romein (Scotland) [2018] UKSC 6, Part One". UK Supreme Court Blog.

- The Advocate General for Scotland (Appellant) v Romein (Respondent) (Scotland) [2018] UKSC 6, [2018] A.C. 585 (8 February 2018), Supreme Court (UK)

- "British Nationality Act 1981 (c. 61) - Statute Law Database". Statutelaw.gov.uk. 5 December 2005. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "British Nationality Act 1981 (c. 61) - Statute Law Database". Statutelaw.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- Michael Pumo. "New requirement for EEA British citizenship applicants". Smith Stone Walters.

- Anne Morris. "EEA PR". DavidsonMorris.

- Parkinson, Justin (13 June 2013). "British citizenship test 'like bad pub quiz'". BBC News.

- Brooks, Thom (13 June 2013). "The 'Life in the United Kingdom' Citizenship Test: Is it Unfit for Purpose?". Social Science Research Network. SSRN 2280329. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Become a British Citizen". gov.uk. UK government. 10 June 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "British Nationality Act 1981, SCHEDULE 1, Naturalisation as a British citizen under section 6(1)". The National Archives. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Details (pdf) Archived 14 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Application for naturalisation as a British citizen" (PDF). GOV.UK. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Nationality Policy: general information – all British nationals" (PDF). GOV.UK. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Accepted Professions". Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Link to notice regarding wait times on the UK Border Agency website as of 11 February 2009". Ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- Link to news report on UK Border Agency website dated 11 February 2009 Archived 14 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "European Economic Area and Swiss nationals". Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office.

- "Statutory Instrument 2000 No. 2326". Opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- Brexit : la réforme de l'immigration post-Brexit qui met fin à la libre circulation des travailleurs est adoptée, on rtbf.be (in French), dated 19 May 2020, after Belga.

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/common-travel-area-guidance

- https://extra.ie/2020/03/06/must-see/draft-laws-irish-uk-brexit

- "Passport policy - Treaty Rights" (PDF).

- sections 1, 3, 4, 4A-4I and 5 of the British Nationality Act 1981

- Section 14 of the British Nationality Act 1981

- Section 4B of the British Nationality Act 1981

- "Guide B(OS) Registration as a British citizen" (PDF). Gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Section 2 of the Hong Kong (War Wives and Widows) Act 1996

- Section 2(1) of the British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1997

- Section 1(3) of the British Nationality Act 1981

- Section 1(4) of the British Nationality Act 1981

- Section 1(3A) of the British Nationality Act 1981

- Paragraph 2 of schedule 2 of the British Nationality Act 1981

- Section 4D of the British Nationality Act 1981

- section 4F-4I of the British Nationality Act 1981

- "Legitimation and Domicile" (PDF). Gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Nationality policy: children of unmarried parents" (PDF). Gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Section 3(2) of the British Nationality Act 1981

- Section 3(5) of the British Nationality Act 1981

- Section 13 of the British Nationality Act 1981

- "Home Office Nationality instructions (Chapter 9: Registration of Minors at Discretion)" (PDF).

- "Guidance: Intercountry adoption and British citizenship". Gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Letter from the Director of the INPD to the Home Secretary" (PDF). 19 June 2002. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "UK | UK Politics | UK to right 'immigration wrong'". BBC News. 5 July 2002. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "britishcitizen.info" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200506/ldlwa/060228wa1.pdf

- "britishcitizen.info" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- "UK Border Agency | How do I give up British citizenship or another form of British nationality?". Bia.homeoffice.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- Ian Cobain. "Obama's secret kill list – the disposition matrix". the Guardian.

- CITIZENSHIP REMOVAL RESULTING IN STATELESSNESS - FIRST REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT REVIEWER ON THE OPERATION OF THE POWER TO REMOVE CITIZENSHIP OBTAINED BY NATURALISATION FROM PERSONS WHO HAVE NO OTHER CITIZENSHIP, DAVID ANDERSON Q.C., April 2016

- "The Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006 (Commencement No. 1) Order 2006". Opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "Apply to the Special Immigration Appeals Commission - GOV.UK" (PDF).

- "British Nationality Act 1981". UK Government. 40(2)(c). Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- Jamie Grierson (7 October 2018). "Sajid Javid 'taking UK down dangerous road' by expanding citizenship stripping". The Obsever. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Kamila Shamsie (17 November 2018). "Exiled: the disturbing story of a citizen made unBritish". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "Deprivation of citizenship". WhatDoTheyKnow. 14 July 2010.

- "Multiple nationality and multiple citizenship". Richmond Chambers.

- "Liste complète". Bureau des Traités.

- "Recherches sur les traités". Bureau des Traités.

- "United Kingdom". European Union. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Article 20(2)(c) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- Rights abroad: Right to consular protection: a right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other Member States when in a non-EU Member State, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state (Article 23): this is due to the fact that not all member states maintain embassies in every country in the world (14 countries have only one embassy from an EU state). Antigua and Barbuda (UK), Barbados (UK), Belize (UK), Central African Republic (France), Comoros (France), Gambia (UK), Guyana (UK), Liberia (Germany), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (UK), San Marino (Italy), São Tomé and Príncipe (Portugal), Solomon Islands (UK), Timor-Leste (Portugal), Vanuatu (France)

- "Treaty on the Function of the European Union (consolidated version)". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1580206007232&uri=CELEX%3A12019W/TXT%2802%29

- "Global Ranking - Visa Restriction Index 2017" (PDF). Henley & Partners. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- "Visa Openness Report 2016" (PDF). World Tourism Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "The 41 nationalities with the best quality of life". www.businessinsider.de. 6 February 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

External links

- Home Office Nationality Instructions: Volume 1, Volume 2

- British Nationality Acts: 1981, 1965, 1964, 1958, 1948, 1772, 1730

- Thom Brooks - The 'Life in the United Kingdom' Citizenship Test: Is It Unfit for Purpose? report 2013

- British Nationality Acts, summary at www.gov.uk of the main Acts from 1844 to 2002 relevant to British nationality and their principal effects, identifying provisions still in force. Includes Acts named "Aliens Act", "Naturalization Act", etc., not restricted to those named "British Nationality Act".

- Online tool to check if one is a British citizen by the British government