Owain Lawgoch

Owain Lawgoch (English: Owain of the Red Hand, French: Yvain de Galles), full name Owain ap Thomas ap Rhodri (c. 1330 – July 1378), was a Welsh soldier who served in Spain, France, Alsace, and Switzerland. He led a Free Company fighting for the French against the English in the Hundred Years' War. As the last politically active descendant of Llywelyn the Great in the male line, he was a claimant to the title of Prince of Gwynedd and of Wales.

Genealogy

Following the death of Llywelyn the Last in 1282 and the execution of his brother and successor Dafydd ap Gruffudd in 1283, Gwynedd paid fealty to and accepted English rule. Llywelyn's daughter Gwenllian ferch Llywelyn was committed to a nunnery at Sempringham, while the sons of Dafydd were kept in Bristol Castle until their deaths. Another of Llywelyn's brothers, Rhodri ap Gruffydd, renounced his rights in Gwynedd and spent much of his life in England as a royal pensioner.[1] His son Thomas inherited lands in England in Surrey, Cheshire and Gloucestershire.[1]

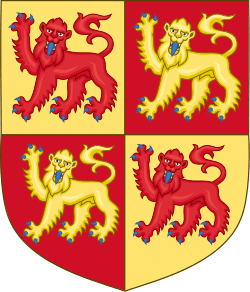

Rhodri was content to end his life as a country gentleman in England, and though his son Thomas ap Rhodri used the four lions of Gwynedd on his seal he made no attempt to win his inheritance.[1] Owain, his only son, was born in Surrey, where his grandfather had acquired the manor of Tatsfield. Tatsfield, a small village only 17 miles from the centre of London, still has Welsh place names e.g. Maesmawr Road (trans: Great Field Road). Thomas died in 1363 and Owain returned from abroad to claim his patrimony in 1365. Owain Lawgoch was in French service by 1369 and his lands in Wales and England were confiscated.[2]

Family tree

| Llywelyn the Great 1173–1195–1240 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gruffydd ap Llywelyn 1198–1244 | Dafydd ap Llywelyn 1212–1240–1246 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owain Goch ap Gruffydd d. 1282 | Llywelyn ap Gruffudd 1223–1246–1282 | Dafydd ap Gruffydd 1238–1282–1283 | Rhodri ap Gruffudd 1230–1315 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gwenllian of Wales 1282–1337 | Llywelyn ap Dafydd 1267–1283–1287 | Owain ap Dafydd 1265–1287–1325 | Tomas ap Rhodri 1300–1325–1363 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owain Lawgoch 1330–1378 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Military career

The year in which Owain entered the service of the king of France is uncertain. Froissart claims that he fought on the French side at the Battle of Poitiers, but there is no other evidence to support this. He was however deprived of his English lands in 1369, suggesting he was in the service of the French as leader of a Free Company when the period of truce between France and England following the Treaty of Brétigny ended and hostilities resumed in 1369.[1][2] His French name was Yvain de Galles (Owen of Wales).[2]

Owain's company consisted largely of Welshmen, many of whom remained in French service for many years.[3] The second in command of this company was Ieuan Wyn, known to the French as le Poursuivant d'Amour, a descendant of Ednyfed Fychan, Seneschal of Gwynedd under Owain's ancestors. Owain also received financial support while in France from Ieuan Wyn's father, Rhys ap Robert. While in French service Owain had good relations with Bertrand du Guesclin and others and gained the support of Charles V of France.[3]

Welsh soldiery and longbowmen who had fought for Edward I in his campaigns in North Wales remained armed and sold their services to Norman kings in their battles in Scotland and at Crecy and Poitiers. Ironically, the Norman attempt to conquer Wales set in train events which reignited Welsh identity and raised up new Welsh military leaders such as Owain claiming descent from the ancient Princes of Wales.[4]

In May 1372 in Paris, Owain announced that he intended to claim the throne of Wales. He set sail from Harfleur with money borrowed from Charles V.[2] Owain first attacked the island of Guernsey, and was still there when a message arrived from Charles ordering him to abandon the expedition in order to go to Castile to seek ships to attack La Rochelle.[1] Owain defeated an English and Gascon force at Soubise later that year, capturing Sir Thomas Percy and Jean de Grailly, the Captal de Buch. Another invasion of Wales was planned in 1373 but had to be abandoned when John of Gaunt launched an offensive. In 1374 he fought at Mirebau and at Saintonge. In 1375 Owain was employed by Enguerrand de Coucy to help win Enguerrand's share of the Habsburg lands due to him as nephew of the former Duke of Austria. However, during the Gugler War they were defeated by the forces of Bern and had to abandon the expedition.[1][2]

In 1377 there were reports that Owain was planning another expedition, this time with help from Castile. The alarmed English government sent a spy, the Scot John Lamb, to assassinate Owain, who had been given the task of besieging Mortagne-sur-Gironde in Poitou.[1] Lamb gained Owain's confidence and became his chamberlain, which gave him the opportunity to stab Owain to death in July 1378, something Walker described as 'a sad end to a flamboyant career'.[2] The Issue Roll of the Exchequer dated 4 December 1378 records "To John Lamb, an esquire from Scotland, because he lately killed Owynn de Gales, a rebel and enemy of the King in France ... £20".

With the assassination of Owain Lawgoch the senior line of the House of Aberffraw became extinct.[1][4] As a result, the claim to the title 'Prince of Wales' fell to the other royal dynasties, of Deheubarth and Powys. The leading heir in this respect was Owain ap Gruffudd of Glyndyfrdwy, who was descended from both dynasties.[2][4]

Owain in legend

A number of legends grew around Owain, of which one version from Cardiganshire runs as follows. Dafydd Meurig of Betws Bledrws was helping to drive cattle from Cardiganshire to London. On the way he cut himself a hazel stick, and was still carrying it when he encountered a stranger on London Bridge. The stranger asked Dafydd where he had cut the stick, and ended up accompanying him back to Wales to the place where the stick had been cut. The stranger told Dafydd to dig under the bush, and this revealed steps leading down to a large cave illuminated by lamps, where a man seven feet tall with a red right hand was sleeping. The stranger told Dafydd that this was Owain Lawgoch "who sleeps until the appointed time; when he wakes he will be king of the Britons".[1]

The quarry reservoir at Aberllefenni in Gwynedd was once known as Llyn Owain Lawgoch and there is a story linking him with the nearby mansion, Plas Aberllefenni, recorded in "Trem Yn Ol" by J. Arthur Williams.

In Guernsey, Owain is remembered as Yvon de Galles. He and his Aragonese mercenaries have been absorbed into the island's folklore as an invasion of diminutive but handsome fairies from across the sea. The story goes that the shipwrecked king of the fairies was found unconscious on a Guernsey shore by a girl named Lizabeau. When he awoke, he fell in love with her and carried her across the sea to be his queen. However, the other fairies soon decided that they wanted Guernsey brides, and invaded the island. The men of the island fought bravely but were slaughtered wholesale, except for two men who hid in an oven. The fairies then took Guernsey wives, which is said to be the reason for the typical Guernseyman's dark hair and short stature.[5]

Further reading

- A. D. Carr (1991). Owen of Wales: The End of the House of Gwynedd. University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-1064-8.

- R. R. Davies (1991). The age of conquest: Wales 1063–1415. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820198-2.

References

- Carr, Antony (1995). Medieval Wales. Basingstoke: Macmillan. pp. 103–6.

- Walker, David (1990). Medieval Wales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–167.

- Davies, R R (1997). The Revolt of Owain Glyndwr. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 86–87.

- Davies, R R (2000). The Age of Conquest: Wales 1063–1415 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 436.

- Folklore of Guernsey by Marie de Garis (1986) ASIN: B0000EE6P8