Romanichal

Romanichal Travellers (UK: /ˈrɒmənɪtʃæl/ US: /-ni-/),[6] (more commonly known as English Gypsies or English Travellers) are a Romani sub-group in the United Kingdom and other parts of the English-speaking world.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 290,000 worldwide | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 163,000 (estimate)[1] | |

| 103,000 (estimate)[2] | |

| 14,000 (estimate)[3] | |

| 6,400 (estimate)[4] | |

| 3,800 (estimate)[3] | |

| 1,400 (estimate)[5] | |

| Languages | |

| English and Angloromani | |

| Religion | |

| Evangelicalism, Protestant, Pentecostalism, Atheism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Romani people, Kale (Welsh Romanies), Scottish Gypsy and Traveller groups (specifically Scottish Lowland Travellers), Norwegian and Swedish Travellers, Finnish Kale, Irish Travellers | |

| Part of a series on |

| Romani people |

|---|

|

Diaspora

|

|

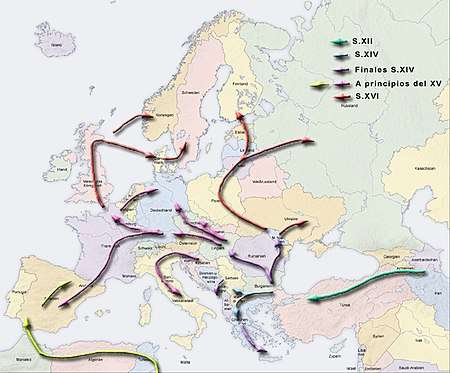

Romanichal Travellers are thought to have arrived in the Kingdom of England in the 16th century. They are very closely related to the Welsh Kale, Scottish Lowland Travellers, Norwegian & Swedish Romanisæl Travellers and Finnish Kale.

Etymology

The word "Romanichal" is derived from Romani chal, where chal is Angloromani for "fellow".[7][8]

Distribution

Nearly all Romanichal Travellers in Britain live in England, with smaller communities in South Wales, Northeast Wales, and the Scottish Borders. They can be found all over these areas, with counties like Kent, Surrey, Hampshire, Cambridgeshire, Gloucestershire and Yorkshire have especially high concentrations of Romanichal communities.[9]

The Romanichal diaspora emigrated from Great Britain to other parts of the English-speaking world. Based on some estimates, there are now more people of Romanichal descent in the United States than in Britain.[10][11] They are also found in smaller numbers in South Africa, Australia, Canada and New Zealand, and there is a small Romanichal community in Malta who are descended from British Romanichal migrants who moved there during colonial times. In the US most Romanichal are in the Deep South and New England regions. Most South African Romanichal are in the Cape region, Most Canadian Romanichal are in the Vancouver region, most New Zealand Romanichal are in the Auckland region and most Australian Romanichal are in the Eastern States of Australia.

In Great Britain, there is a sharp North-South divide between Romanichal Travellers. Southern Romanichal Travellers live in the Southeast, Southwest, Midlands, East Anglia and South Wales, and Northern Romanichal Travellers live in the Northwest, Yorkshire, Scottish Borders and Northeast of Wales. The two groups' dialects differ in accent and vocabulary.[12]

Language

The Romani people in England are thought to have spoken the Romani language until the 19th century, when it was replaced by English and Angloromani, a creole language that combines the syntax and grammar of English with the Romani lexicon.[13] Most Romanichals also speak English.

There are two dialects of Angloromani, Southern Angloromani (Spoken in the Southeast, Southwest, Midlands, East Anglia and South Wales) and Northern Angloromani (Spoken in the Northeast, Northwest, Yorkshire, Scottish Borders and Northeast of Wales). These two dialects along with the accents that accompany them have led to two regional Romanichal Traveller identities forming, these being the Southern Romanichal identity and the Northern Romanichal Traveller identity.[14]

Many Angloromani words have been incorporated into English, particularly in the form of British slang.[15]

History

The Romani people have origins in India, specifically Rajasthan[16] and began migrating westwards from the 11th century. The first groups of Romani people arrived in Great Britain by the end of the 16th century, escaping conflicts in Southeastern Europe (such as the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans).

In 1506 there are recorded Romani persons in Scotland,[17] arrived from Spain and to England in 1512.[17] Soon the leadership passed laws aimed at stopping the Romani immigration and at the assimilation of those already present.

During the reign of Henry VIII, the Egyptians Act (1530) banned Romanies from entering the country and required those living in the country to leave within 16 days. Failure to do so could result in confiscation of property, imprisonment and deportation. During the reign of Mary I the act was amended with the Egyptians Act (1554), which removed the threat of punishment to Romanies if they abandoned their "naughty, idle and ungodly life and company" and adopted a settled lifestyle, but it increased the penalty for noncompliance to death.

In 1562 a new law offered Romanies born in England and Wales the possibility of becoming English subjects if they assimilated into the local population. Despite persecution and this new option, the Romani were forced into a marginal lifestyle and subjected to continuous discrimination from the state authorities and many non-Romanies. In 1596, 106 men and women were condemned to death at York just for being Romani, and nine were executed.[18] Samuel Rid authored two early works about them in the early 17th century.[19]

From the 1780s, gradually, the anti-Romani laws were repealed, although not all. The identity of the Romanichals was formed between the years 1660 and 1800, as a Romani group living in Britain.

Persecution

Racism against Romanichal and other travelling peoples is still endemic within Britain.[20] In 2008 the Romani experienced a higher degree of racism than any other group in the UK, including asylum-seekers, and a Mori poll indicated that a third of UK residents admitted to being prejudiced against Romani.[20]

Shipments to the Americas, Caribbean and Australia

England began to deport Romanichals, principally to Norway, as early as 1544.[21][22] The process was continued and encouraged by Elizabeth I and James I.[23]

The Finnish Kale, a Romani group in Finland, maintain that their ancestors had originally been a Romani group who travelled from Scotland,[24] supporting the idea that they and the Scandinavian Travellers/Romani are distantly related to present-day Scottish Romani and English Romanichals.[25][26]

In 1603 an Order in Council was made for the transportation of Romanichal to the Low Countries, France, Newfoundland, Spain, and the West Indies. Other European countries forced the further transport of the Romani of Britain to the Americas.

Many times those deported in this manner did not survive as an ethnic group, because of the separations after the round up, the sea passage and the subsequent settlement as slaves, all destroying their social fabric. At the same time, voluntary emigration began to the English overseas possessions. Romani groups which survived continued the expression of the Romani culture there.

In the years following the American War of Independence, Australia was the preferred destination for Romanichal transportation due to its use as a penal colony. The exact number of British Romani deported to Australia is unknown. It has been suggested that three Romanichal were present on the First Fleet,[27] one of whom was thought to be James Squire[27] who founded Australia's first commercial brewery in 1798, and whose grandson James Farnell who became the first native-born Premier of New South Wales in 1877. The total Romani population seems to be an extremely low number when we consider that British Romani people made up just 0.01% of the original 162,000 convict population.[27] However, it has been suggested that Romanichal were one of the main target groups and were discriminated against due to the transportation laws of England in the mid-18th century.[28]

It is often difficult to distinguish British Romani people of Wales and England from the majority of non-Romani convicts at the time, therefore the precise number of British Romanies transported is not known, although there are occurrences of Romani names and possible families within the convict population; however it is unclear if such people were members of the established Romani community.[28] Fragmentary records do exist and it is thought with confidence at least fifty or more British Romanies may have been transported to Australia, although the actual figure could be higher.[27] What is clear is that such deportation (as for all convicts) was particularly harsh:

"For Romani convicts transportation meant social and psychological death; exiled they had little hope of returning to England to re-establish family ties, cultural roots, continuous expression and validation that would have revived their Romani identity in the convict era."[27]

One, however, is known to have returned. Henry Lavello (or Lovell) was repatriated with a full pardon with a son born to an Aboriginal woman who accompanied him back to England.[27][28]

Slavery

In the 17th century Oliver Cromwell shipped Romanichals as slaves to the American southern plantations[29] and there is documentation of English Romanies being owned by freed black slaves in Jamaica, Barbados, Cuba, and Louisiana.[23][29][30] Gypsies, according to the legal definition, were anyone identifying themselves to be Egyptians or Gypsies.[31][32] The works of George Borrow reflect the influences this had on the Romani Language of England and others contain references to Romanies being bitcheno pawdel or Bitchade pardel, to be "sent across" to America or Australia, a period of Romani history not forgotten by Romanies in Britain today.

Culture

Historically, Romanichals earned a living doing agricultural work and would move to the edges of towns for the winter months. There was casual work available on farms throughout the spring, summer and autumn months; spring would start with seed sowing, planting potatoes and fruit trees, early summer with weeding, and there would be a succession of harvests of crops from summer to late autumn. Of particular significance was the hop industry, which employed thousands of Romanichals both in spring for vine training and for the harvest in early autumn. Winter months were often spent doing casual labour in towns or selling goods or services door to door.[33]

Mass industrialisation of agriculture in the 1960s led to the disappearance of many of the casual farm jobs Romanichals had traditionally carried out.[34]

During the 20th century onwards Romanichals became, and remain, the mainstay of asphalt paving, hawking, horse dealing, fortune telling, scrap metal dealing, tree surgery, tarmacking, travelling funfairs, and wooden rose making.[35] They have also produced notable boxers such as Henry Wharton and Billy Joe Saunders as well as some notable footballers like Freddy Eastwood Ben Hughes Australian and World Whip Cracking champion, and journalists, psychotherapists, nurses and all manner of professions.[36]

A didicoy (Angloromani; didikai, also diddicoy, diddykai) is a person of mixed Romany and Gorger (non-Romanichal) blood. [37]

Travel

Originally, Romanichals would travel on foot, or with light, horse-drawn carts, and would build bender tents where they settled for a time, as is typical of other Romani groups. A Bender is a type of tent constructed from a frame of bent hazel branches (hazel is chosen for its straightness and flexibility), covered with canvas or tarpaulin.

Around the mid- to late 19th century, Romanichals started using wagons that incorporated living spaces on the inside. These they called Vardos and were often brightly and colorfully decorated on the inside and outside. In the present day, Romanichals are more likely to live in caravans or houses.

Over 60% of 21st-century Romanichal families live in houses of bricks and mortar whilst the remaining 40% still live in various forms of traditional Traveller modes of transport, such as caravans, trailers or static caravans (a small minority still live in Vardos).

According to the Regional Spatial Strategy caravan count for 2008, there were 13,386 caravans owned by Romani in the West Midlands region of England, whilst a further 16,000 lived in bricks and mortar. Of the 13,386 caravans, 1,300 were parked on unauthorised sites (that is, on land where Romani were not given permission to park). Over 90% of Britain's travelling Romanichals live on authorised sites where they pay full rates (council tax).[7][38]

On most Romanichal Traveller sites there are usually no toilets or showers inside caravans because in Romanichal culture this is considered unclean, or 'mochadi'. Most sites have separate utility blocks with toilets, sinks and electric showers. Many Romanichals will not do their laundry inside, especially not underwear, and subsequently many utility blocks also have washing machines. In the days of horse-drawn wagons and Vardos, Romanichal women would do their laundry in a river, being careful to wash upper body garments further upstream from underwear and lower body garments, and personal bathing would take place much further downstream. In some modern trailers, a double wall separates the living areas from the toilet and shower.[36]

Due to the (British) Caravan Sites Act 1968 which greatly reduced the number of caravans allowed to be pitched on authorised sites, many Romanichals cannot find legal places on sites with the rest of their families.

Like most Itinerant groups, Romanichals travel around for work, usually following set routes and set stopping places (called ‘atching tans’) which have been established for hundreds of years. Many traditional stopping places were established before land ownership changed and any land laws were in place. Many atching tans were established by feudal land owners in the Middle Ages, when Romani would provide agricultural or manual labour services in return for lodgings and food.

Today, most Romani travel within the same areas that were established generations ago. Most people can trace their presence in an area back over a hundred or two hundred years. Many traditional stopping places were taken over by local government or by settled individuals decades ago and have subsequently changed hands numerous times; however Romani have long historical connections to such places and do not always willingly give them up. Most families are identifiable by their traditional wintering base, where they will stop travelling for the winter, and this place will be technically where a family is ‘from’.

British acts of legislation

The Enclosure Act of 1857 created the offence of injury or damage to village greens and interruption to its use or enjoyment as a place of exercise and recreation. The Commons Act 1876 makes encroachment or inclosure of a village green, and interference with or occupation of the soil unlawful unless it is with the aim of improving enjoyment of the green.

The Caravan Sites and Control of Development Act 1960 states that no occupier of land shall cause or permit the land to be used as a caravan site unless he is the holder of a site licence. It also enables a district council to make an order prohibiting the stationing of caravans on common land, or a town or village green. These acts had the overall effect of preventing travellers using the vast majority of their traditional stopping places.

The Caravan Sites Act 1968 required local authorities to provide caravan sites for travellers if there was a demonstrated need. This was resisted by many councils who would claim that there were no Romanichals living in their areas.[39] The result was that insufficient pitches were provided for travellers, leading to a situation whereby holders of a pitch could no longer travel, for fear of losing it.

The crisis of the 1960s decade, caused by the Caravan Sites Act 1968 (stopping new private sites being built until 1972), led to the appearance of the "British Gypsy Council" to fight for the rights of the Romanichals.[40]

In the UK, the issue of "Travellers" (referring to Romanichal Travellers, Irish Travellers, Funfair Travellers (Showman) as well as other groups) became a 2005 general election issue, with the leader of the Conservative Party promising to review the Human Rights Act 1998. This law, which absorbs the European Convention on Human Rights into UK primary legislation, is seen by some to permit the granting of retrospective planning permission. Severe population pressures and the paucity of greenfield sites have led to travellers purchasing land and setting up residential settlements very quickly, thus subverting the planning restrictions.[36]

Romanichal Travellers and Irish Travellers argued in response that thousands of retrospective planning permissions are granted in Britain in cases involving non-Romani applicants each year and that statistics showed that 90% of planning applications by Travellers were initially refused by local councils, compared with a national average of 20% for other applicants, disproving claims of preferential treatment favouring Travellers.[41]

They also argued that the root of the problem was that many traditional stopping-places had been barricaded off and that the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 passed by the previous Conservative government had effectively criminalized their community, for example by removing local authorities’ responsibility to provide sites, thus leaving the travellers with no option but to purchase unregistered new sites themselves.[42]

See also

- Didicoy, a mixed-blooded Romanichal

- Gordon Boswell Romany Museum

- Jumping the broom (Romani people)

- List of Romanichals

- List of Romanichal-related depictions & documentaries

- Vardoes

- Gypsy Cob

Groups:

References

- (Ethnic origin) The shows 153,000 people claiming English Romanichal ancestry.

- The shows 170,000 people claiming English Romanichal ancestry.

- shows 14,000 people claiming English Romanichal ancestry.

- (Ancestry) The reports 5,300 people of English Romanichal ancestry.

- shows 1,200 people claiming English Romanichal ancestry.

- Oxford English Dictionary (2003)

- Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition 1989, "Romany3, n. and a."

- Borrow, George Henry (2007). Romano Lavo-Lil. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1434679260.

- "Gypsies and Traveller Policy in Wales" (PDF). ec.europa.eu.

- Joshua Project, 2010, Gypsy, English, Romanichal of South Africa.

- "Angloromani". Ethnologue. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- https://www.salford.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1155666/Migrant_Roma_in_the_UK_final_report_October_2013.pdf

- University of Manchester Romani Project. "The Anglo-Romani project". Archived from the original on 18 February 2007.

- https://www.equalrightstrust.org/ertdocumentbank/ERR8_Brian_Foster_and_Peter_Norton.pdf

- John Ayto (2006). Movers and Shakers: A Chronology of Words that Shaped Our Age. Oxford University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-19-861452-4.

- Carol Silverman (14 February 2012). Romani Routes: Cultural Politics and Balkan Music in Diaspora. Oxford University Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-19-991022-9.

- Smart, B C; Crofton, H T (1875). The Dialect of the English Gypsies (2nd ed.). Covent Garden: Asher & Company.

- Timbers, Frances (20 April 2016). 'The Damned Fraternitie': Constructing Gypsy Identity in Early Modern England, 1500–1700. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-317-03651-7.

- "Gypsies in England". Notes and Queries. London: George Bell. Eleventh (287): 326. 28 April 1855.

- Shields, Rachel (6 July 2008). "No blacks, no dogs, no Gypsies". The Independent. London.

- Weyrauch, Walter Otto (2001). Gypsy Law: Romani Legal Traditions and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520924277. OCLC 49851981.

- Bergman, Nils Gösta (1964). Slang och hemliga språk (in Swedish). Stockholm : Prisma.

- MacRitchie, David (1894). Scottish Gypsies under the Stewarts. Edinburgh: David Douglas. hdl:2027/mdp.39015027038119. ISBN 0766175839. OCLC 1083268040.

- "Romani, Kalo Finnish". Ethnologue.

- Fraser, Angus M (1995). The Gypsies. Mazal Holocaust Collection. (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 120. ISBN 0631196056. OCLC 32128826.

- Allan Etzler (1944). Zigenarna och deras avkomlingar i Sverige: Historia och språk. H. Geber. cited in: Fraser (1995)

- Acton, Thomas Alan; Mundy, Gary (1997). Romani culture and Gypsy identity. Hatfield, Hertfordshire: University of Hertfordshire Press. ISBN 0900458763. OCLC 37396992.

- Donohoe, James Hugh (1991). The Forgotten Australians: The Non Anglo or Celtic Convicts and Exiles. North Sydney: J.H. Donohoe. ISBN 0731651294. OCLC 29430393.

- Hancock, Ian F (1988). The Pariah Syndrome: An Account of Gypsy Slavery and Persecution (2nd rev. ed.). Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers. ISBN 0897200799. OCLC 16071858.

- Chambers, Robert (1858). Domestic annals of Scotland from the Reformation to the Revolution. II. Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers. hdl:2027/mdp.39015011674614.

- Smith, Abbot Emerson (1947). Colonists in Bondage: White Servitude and Convict Labor in America, 1607–1776. New York: Norton. ISBN 0393005925. OCLC 31734445.

- Beier, A L (1985). Masterless Men: The Vagrancy Problem in England 1560–1640. London: Methuen. ISBN 0416390102. OCLC 11971210.

- "Twelfth Generation". weareallrelated.info. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- BBC Kent Romany Roots. "Romany History".

- https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/iris/2014/Experts-by-Experience--JRTF-Report-Oct-2014.pdf

- Thomas Alan Acton; David Gallant (2008). Romanichal Gypsies. Wayland. ISBN 978-0-7502-5578-3.

- "Didicoy definition and meaning". Collins English Dictionary. 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Diacon, Diane (2007). Out in the Open: Providing Accommodation, Promoting Understanding and Recognising Rights of Gypsies and Travellers. Coalville: Building and Social Housing Foundation. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-901742-02-2. OCLC 572779016.

- "The Patrin Web Journal - Timeline of Romani (Gypsy) History". OoCities.org. Archived from the original on October 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- "Gypsies and Irish Travellers: The facts". Commission on Racial Equality (UK). Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- "Gypsies". Inside Out - South East. BBC. 19 September 2005.

External links

- 'Gypsies' in the United States

- Salo, M., 'Romnichel economic and social organization in urban New England, 1850–1930,' in Salo, M. ed. Urban Gypsies, special issue of Urban Anthropology, 2.3/4 (1982), 273-313

- Places in London associated with Romany Gypsies

- Romani Cymru Project (Wales UK) - An archival Initiative of Sipsi Cymreig, Welsh Gypsies

- Gypsywaggons.co.uk

- Hamilton, Rachel Segal (8 July 2019). "The private world of London's Traveler community". CNN.