Northern Isles

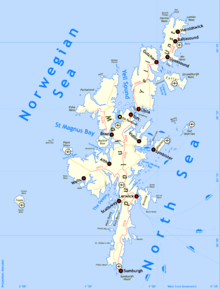

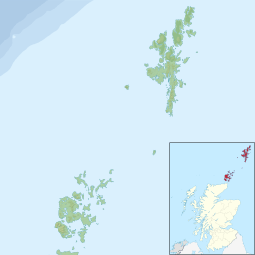

The Northern Isles (Scots: Northren Isles; Scottish Gaelic: Na h-Eileanan a Tuath; Old Norse: Norðreyjar) are a pair of archipelagos off the north coast of mainland Scotland, comprising Orkney and Shetland. The climate is cool and temperate and much influenced by the surrounding seas. There are a total of 26 inhabited islands with landscapes of the fertile agricultural islands of Orkney contrasting with the more rugged Shetland islands to the north, where the economy is more dependent on fishing and the oil wealth of the surrounding seas. Both have a developing renewable energy industry. They also share a common Pictish and Norse history. Both island groups were absorbed into the Kingdom of Scotland in the 15th century and remained part of the country following the formation of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707, and later the United Kingdom after 1801. The islands played a significant naval role during the world wars of the 20th century.

| Location | |

|---|---|

| |

Northern Isles Northern Isles shown within Scotland | |

| OS grid reference | HY99 |

| Coordinates | 59°50′N 2°00′W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | British Isles |

| Area | 2,464 km2[1] |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 44,516[2] |

| Population density | 18/km2 |

| Largest settlement | Kirkwall |

Tourism is important to both archipelagos, with their distinctive prehistoric ruins playing a key part in their attraction, and there are regular ferry and air connections with mainland Scotland. The Scandinavian influence remains strong, especially in relation to local folklore, and both island chains have strong, although distinct, local cultures. The place-names of the islands are dominated by their Norse heritage, although some may retain pre-Celtic elements.

Geography

The phrase "Northern Isles" generally refers to the main islands of the Orkney and Shetland archipelagos. Island of Stroma, which lies between mainland Scotland and Orkney, is part of Caithness, and so falls under Highland council area for local government purposes, not Orkney. It is, however, clearly one of the "northern isles" of Scotland.[3] Fair Isle and Foula are outliers of Shetland, but would normally be considered as part of Shetland and thus the Northern Isles. Similarly, Sule Skerry and Sule Stack, although distant from the main group, are part of Orkney and technically amongst the Northern Isles. However, the other small islands that lie off the north coast of Scotland are in Highland and thus not usually considered to be part of the Northern Isles.[4]

Orkney is situated 16 kilometres (10 mi) north of the coast of mainland Scotland, from which it is separated by the waters of the Pentland Firth. The largest island, known as the "Mainland" has an area of 523.25 square kilometres (202.03 sq mi), making it the sixth largest Scottish island.[5] The total population in 2001 was 19,245 and the largest town is Kirkwall.[6] Shetland is around 170 kilometres (110 mi) north of mainland Scotland, covers an area of 1,468 square kilometres (567 sq mi) and has a coastline 2,702 kilometres (1,679 mi) long.[7] Lerwick, the capital and largest settlement, has a population of around 7,500 and about half of the archipelago's total population of 22,000 people live within 16 kilometres (10 mi) of the town.[8] Orkney has 20 inhabited islands and Shetland a total of 16.[9][10]

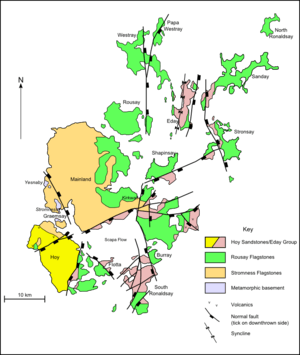

Geology

The superficial rock of Orkney is almost entirely Old Red Sandstone, mostly of Middle Devonian age.[11] As in the neighbouring mainland county of Caithness, this sandstone rests upon the metamorphic rocks of the Moine series, as may be seen on the Orkney Mainland, where a narrow strip of the older rock is exposed between Stromness and Inganess, and again on the small island of Graemsay.[12]

Middle Devonian basaltic volcanic rocks are found on western Hoy, on Deerness in eastern Mainland and on Shapinsay. Correlation between the Hoy volcanics and the other two exposures has been proposed, but differences in chemistry means this remains uncertain.[13] Lamprophyre dykes of Late Permian age are found throughout Orkney.[14] Glacial striation and the presence of chalk and flint erratics that originated from the bed of the North Sea demonstrate the influence of ice action on the geomorphology of the islands. Boulder clay is also abundant and moraines cover substantial areas.[15]

The geology of Shetland is quite different. It is extremely complex, with numerous faults and fold axes. These islands are the northern outpost of the Caledonian orogeny and there are outcrops of Lewisian, Dalriadan and Moine metamorphic rocks with similar histories to their equivalents on the Scottish mainland. There are also small Old Red Sandstone deposits and granite intrusions. The most distinctive feature is the ultrabasic ophiolite, peridotite and gabbro on Unst and Fetlar, which are remnants of the Iapetus Ocean floor.[16] Much of Shetland's economy depends on the oil-bearing sediments in the surrounding seas.[17]

Geological evidence shows that at around 6100 BC a tsunami caused by the Storegga Slides hit the Northern Isles, (as well as much of the east coast of Scotland), and may have created a wave of up to 25 metres (82 ft) high in the voes of Shetland where modern populations are highest.[18]

Climate

The Northern Isles have a cool, temperate climate that is remarkably mild and steady for such a northerly latitude, due to the influence of the surrounding seas and the Gulf Stream.[19] In Shetland average peak temperatures are 5 °C (41 °F) in February and 15 °C (59 °F) in August and temperatures over 21 °C (70 °F) are rare.[20][21] The frost-free period may be as little as 3 months.[22]

The average annual rainfall is 982 millimetres (38.7 in) in Orkney[19] and 1,168 millimetres (46.0 in) in Shetland.[21] Winds are a key feature of the climate and even in summer there are almost constant breezes. In winter, there are frequent strong winds, with an average of 52 hours of gales being recorded annually in Orkney.[23] Burradale wind farm in Shetland, which operates with five Vestas V47 660 kW turbines, achieved a world record of 57.9% capacity over the course of 2005 due to the persistent strong winds.[24]

Snowfall is usually confined to the period of November to February and seldom lies on the ground for more than a day. Less rain falls from April to August although no month receives less than an average of 50 mm (2.0 in).[19][20][21] Annual bright sunshine averages 1082 hours in Shetland and overcast days are common.[20]

To tourists, one of the fascinations of the islands is their "nightless" summers. On the longest day in Shetland there are over 19 hours of daylight and complete darkness is unknown. This long twilight is known in the Northern Isles as the "simmer dim". Winter nights are correspondingly long with less than six hours of daylight at midwinter.[25][26] At this time of year the aurora borealis can occasionally be seen on the northern horizon during moderate auroral activity.[27]

Prehistory

There are numerous important prehistoric remains in Orkney, especially from the Neolithic period, four of which form the Heart of Neolithic Orkney UNESCO World Heritage Site that was inscribed in 1999: Skara Brae; Maes Howe; the Stones of Stenness; and Ring of Brodgar.[28] The Knap of Howar Neolithic farmstead situated on the island of Papa Westray is probably the oldest preserved house in northern Europe. This structure was inhabited for 900 years from 3700 BC but was evidently built on the site of an even older settlement.[29][30][31] Shetland is also extremely rich in physical remains of the prehistoric eras and there are over 5,000 archaeological sites all told.[32] Funzie Girt is a remarkable Neolithic dividing wall that ran for 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) across the island of Fetlar,[33][34] although the Iron Age has provided the most outstanding archaeology in Shetland. Numerous brochs were erected at that time of which the Broch of Mousa is the finest preserved example of these round towers.[35] In 2011 the collective site, "The Crucible of Iron Age Shetland" including Broch of Mousa, Old Scatness and Jarlshof joined the UK's "Tentative List" of World Heritage Sites.[36][37]

History, culture and politics

Pictish times

The culture that built the brochs is unknown, but by the late Iron Age the Northern Isles were part of the Pictish kingdom.[38] The main archaeological relics from these times are symbol stones. One of the best examples is located on the Brough of Birsay; it shows three warriors with spears and sword scabbards combined with traditional Pictish symbols.[39][40] The St Ninian's Isle Treasure was discovered in 1958. The silver bowls, jewellery and other pieces are believed to date from approximately 800 AD. O'Dell (1959) stated that "the treasure is the best survival of Scottish silver metalwork from the period" and that "the brooches show a variety of typical Pictish forms, with both animal-head and lobed geometrical forms of terminal".[41][42]

Christianity probably arrived in Orkney in the 6th century and organised church authority emerged in the 8th century. The Buckquoy spindle-whorl found at a Pictish site on Birsay is an Ogham–inscribed artefact whose interpretation has caused controversy although it is now generally considered to be of Irish Christian origin.[43][44]

Norse era

The 8th century was also the time the Viking invasions of the Scottish seaboard commenced and with them came the arrival of a new culture and language for the Northern Isles,[46] the fate of the existing indigenous population being uncertain. According to the Orkneyinga Saga, Vikings then made the islands the headquarters of pirate expeditions carried out against Norway and the coasts of mainland Scotland. In response, Norwegian king Harald Hårfagre ("Harald Fair Hair") annexed the Northern Isles in 875 and Rognvald Eysteinsson received Orkney and Shetland from Harald as an earldom as reparation for the death of his son in battle in Scotland. (Some scholars believe that this story is apocryphal and based on the later voyages of Magnus Barelegs.)[47]

The islands were fully Christianised by Olav Tryggvasson in 995 when he stopped at South Walls on his way from Ireland to Norway. The King summoned the jarl Sigurd the Stout and said, "I order you and all your subjects to be baptised. If you refuse, I'll have you killed on the spot and I swear I will ravage every island with fire and steel." Unsurprisingly, Sigurd agreed and the islands became Christian at a stroke,[45] receiving their own bishop in the early 11th century.[48]

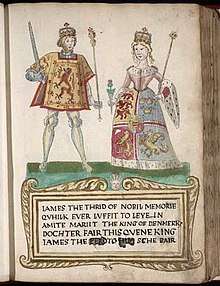

Annexation by Scotland

In the 14th century, Orkney and Shetland remained a Norwegian province, but Scottish influence was growing. Jon Haraldsson, who was murdered in Thurso in 1231, was the last of an unbroken line of Norse jarls,[49] and thereafter the earls were Scots noblemen of the houses of Angus and St. Clair.[50] In 1468 Shetland was pledged by Christian I, in his capacity as King of Norway, as security against the payment of the dowry of his daughter Margaret, betrothed to James III of Scotland. As the money was never paid, the connection with the crown of Scotland became permanent. In 1470 William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness ceded his title to James III and the following year the Northern Isles were directly annexed to Scotland.[51]

17th, 18th and 19th Centuries

From the early 15th century on the Shetlanders had sold their goods through the Hanseatic League of German merchantmen.[52][53] This trade with the North German towns lasted until the 1707 Act of Union when high salt duties prohibited the German merchants from trading with Shetland. Shetland then went into an economic depression as the Scottish and local traders were not as skilled in trading with salted fish. However, some local merchant-lairds took up where the German merchants had left off, and fitted out their own ships to export fish from Shetland to the Continent. For the independent farmer/fishermen of Shetland this had negative consequences, as they now had to fish for these merchant-lairds.[54]

British rule came at a price for many ordinary people as well as traders. The Shetlanders' nautical skills were sought by the Royal Navy: some 3,000 served during the Napoleonic Wars from 1800 to 1815 and press gangs were rife. During this period 120 men were taken from Fetlar alone and only 20 of them returned home. By the late 19th century 90% of all Shetland was owned by just 32 people, and between 1861 and 1881 more than 8,000 Shetlanders emigrated.[55][56] With the passing of the Crofters' Act in 1886 the Liberal prime minister William Gladstone emancipated crofters from the rule of the landlords. The Act enabled those who had effectively been landowners' serfs to become owner-occupiers of their own small farms.[57]

The Orcadian experience was somewhat different. An influx of Scottish entrepreneurs helped to create a diverse and independent community that included farmers, fishermen and merchants that called themselves comunitatis Orcadie and who proved themselves increasingly able to defend their rights against their feudal overlords.[58][59] In the 17th century, Orcadians formed the overwhelming majority of employees of the Hudson's Bay Company in Canada. The harsh climate of Orkney and the Orcadian reputation for sobriety and their boat-handling skills made them ideal candidates for the rigours of the Canadian north.[60] During this period, burning kelp briefly became a mainstay of the islands' economy. For example, on Shapinsay over 3,048 tonnes (3,000 long tons) of burned seaweed were produced per annum to make soda ash, bringing in £20,000 to the local economy.[61] Agricultural improvements beginning in the 17th century coincided with the enclosure of the commons and in the Victorian era the emergence of large and well-managed farms using a five-shift rotation system and producing high-quality beef cattle.[62] There is little evidence of an Orcadian fishing fleet until the 19th century but it grew rapidly and 700 boats were involved by the 1840s with Stronsay and then later Stromness becoming leading centres of development.[63][Note 1] Many Orcadian seamen became involved in whaling in Arctic waters during the 19th century, although the boats were generally based elsewhere in Britain.[64]

World Wars

Orkney was the site of a naval base at Scapa Flow, which played a major role in World War I. After the Armistice in 1918, the German High Seas Fleet was transferred in its entirety to Scapa Flow while a decision was to be made on its future; however, the German sailors opened the sea-cocks and scuttled all the ships. During World War I the 10th Cruiser Squadron was stationed at Swarbacks Minn in Shetland and during a single year from March 1917 more than 4,500 ships sailed from Lerwick as part of an escorted convoy system. In total, Shetland lost more than 500 men, a higher proportion than any other part of Britain, and there were waves of emigration in the 1920s and 1930s.[65][66]

One month into World War II, the Royal Navy battleship HMS Royal Oak was sunk by a German U-boat at Scapa Flow. As a result barriers were built to close most of the access channels; these had the advantage of creating causeways enabling travellers to go from island to island by road instead of being obliged to rely on ferries. The causeways were constructed by Italian prisoners of war, who also constructed the ornate Italian Chapel.[67] The Scapa Flow base was neglected after the war, eventually closing in 1957.[68]

During World War II a Norwegian naval unit nicknamed the "Shetland Bus" was established by the Special Operations Executive in the autumn of 1940 with a base first at Lunna and later in Scalloway to conduct operations around the coast of Norway. About 30 fishing vessels used by Norwegian refugees were gathered and the Shetland Bus conducted covert operations, carrying intelligence agents, refugees, instructors for the resistance, and military supplies. It made over 200 trips across the sea with Leif Larsen, the most highly decorated allied naval officer of the war, making 52 of them.[69][70]

The problem of a declining population was significant in the post-war years, although in the last decades of the 20th century there was a recovery and life in the islands focused on growing prosperity and the emergence of a relatively classless society.[68]

Modern times

Politics

Due to their history, the islands have a Norse, rather than a Gaelic flavour, and have historic links with the Faroes, Iceland, and Norway. The similarities of both geography and history are matched by some elements of the current political process. Both Orkney and Shetland are represented in the House of Commons as constituting the Orkney and Shetland constituency, which elects one Member of Parliament (MP), the current incumbent being Alistair Carmichael.[71][72][73] Both are also within the Highlands and Islands electoral region for the Scottish Parliament.

However, there are also two separate constituencies that elect one Member of the Scottish Parliament each for Orkney and Shetland by the first past the post system.[74][75] Orkney and Shetland also have separate local Councils which are dominated by independents, that is they are not members of a political party.[76][77][78]

The Orkney Movement, a political party that supported devolution for Orkney from the rest of Scotland, contested the 1987 general election as the Orkney and Shetland Movement (a coalition of the Orkney movement and its equivalent for Shetland). Their candidate, John Goodlad, came 4th with 3,095 votes, 14.5% of those cast, but the experiment has not been repeated.[79]

Transport

Ferry services link Orkney and Shetland to the rest of Scotland, the main routes being Scrabster harbour, Thurso to Stromness and Aberdeen to Lerwick, both operated by NorthLink Ferries.[80][81] Inter-island ferry services are operated by Orkney Ferries and SIC Ferries, which are operated by the respective local authorities and Northlink also run a Lerwick to Kirkwall service.[81][82] The archipelago is exposed to wind and tide, and there are numerous sites of wrecked ships. Lighthouses are sited as an aid to navigation at various locations.[83]

The main airport in Orkney is at Kirkwall, operated by Highland and Islands Airports. Loganair provides services to the Scottish mainland (Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Inverness), as well as to Sumburgh Airport in Shetland. Similar services fly from Sumburgh to the Scottish mainland.[81][84]

Inter-Island flights are available from Kirkwall to several Orkney islands and from the Shetland Mainland to most of the inhabited islands including those from Tingwall Airport. There are frequent charter flights from Aberdeen to Scatsta near Sullom Voe, which are used to transport oilfield workers and this small terminal has the fifth largest number of international passengers in Scotland.[85] The scheduled air service between Westray and Papa Westray is reputedly the shortest in the world at two minutes' duration.[86]

Economics

The very different geologies of the two archipelagos have resulted in dissimilar local economies. In Shetland, the main revenue producers are agriculture, aquaculture, fishing, renewable energy, the petroleum industry (offshore crude oil and natural gas production), the creative industries and tourism.[87] Oil and gas was first landed at Sullom Voe in 1978, and it has subsequently become one of the largest oil terminals in Europe.[88] Taxes from the oil have increased public sector spending in Shetland on social welfare, art, sport, environmental measures and financial development. Three-quarters of the islands' workforce is employed in the service sector[89][90] and Shetland Islands Council alone accounted for 27.9% of output in 2003.[91][92] Fishing remains central to the islands' economy today, with the total catch being 75,767 tonnes (74,570 long tons; 83,519 short tons) in 2009, valued at over £73.2 million.[93]

By contrast, fishing has declined in Orkney since the 19th century and the impact of the oil industry has been much less significant. However, the soil of Orkney is generally very fertile and most of the land is taken up by farms, agriculture being by far the most important sector of the economy and providing employment for a quarter of the workforce.[94] More than 90% of agricultural land is used for grazing for sheep and cattle, with cereal production utilising about 4% (4,200 hectares or 10,000 acres), although woodland occupies only 134 hectares or 330 acres.[95]

Orkney and Shetland have significant wind and marine energy resources, and renewable energy has recently come into prominence. The European Marine Energy Centre is a Scottish Government-backed research facility that has installed a wave testing system at Billia Croo on the Orkney Mainland and a tidal power testing station on the island of Eday.[96] This has been described as "the first of its kind in the world set up to provide developers of wave and tidal energy devices with a purpose-built performance testing facility."[97] Billia Croo also houses an experimental underwater data center run by Microsoft.[98]

Culture

.jpg)

The Northern Isles have a rich folklore. For example, there are many Orcadian tales concerning trows, a form of troll that draws on the islands' Scandinavian connections.[99] Local customs in the past included marriage ceremonies at the Odin Stone that forms part of the Stones of Stenness.[100] The best known literary figures from modern Orkney are the poet Edwin Muir, the poet and novelist George Mackay Brown and the novelist Eric Linklater.[101]

Shetland has a strong tradition of local music. The Forty Fiddlers was formed in the 1950s to promote the traditional fiddle style, which is a vibrant part of local culture today.[102] Notable exponents of Shetland folk music include Aly Bain and the late Tom Anderson and Peerie Willie Johnson. Thomas Fraser was a country musician who never released a commercial recording during his life, but whose work has become popular more than 20 years after his untimely death in 1978.[103]

Language

The Norn language formerly spoken in the islands, a descendant of Old Norse, a language of the Norse people, brought in by the Vikings, became extinct in the 18th or 19th century.[104][105] The local dialects of the Scots language, collectively known as Insular Scots, are highly distinctive and retain strong Norn influences.[106]

Island names

The etymology of the island names is dominated by Norse influence. There follows a listing of the derivation of all the inhabited islands in the Northern Isles.

Shetland

The oldest version of the modern name Shetland is Hetlandensis recorded in 1190 becoming Hetland in 1431 after various intermediate transformations.[107][108] This then became Hjaltland in the 16th century.[109] As Shetland's Norn was gradually replaced by Scots Hjaltland became Ȝetland. When use of the letter yogh was discontinued, it was often replaced by the similar-looking letter z, hence Zetland, the mispronounced form used to describe the pre-1975 county council. However the earlier name is Innse Chat – the island of the cats (or the cat tribe) as referred to in early Irish literature and it is just possible that this forms part of the Norse name.[107][108] The Cat tribe also occupied parts of the northern Scottish mainland – hence the name of Caithness via the Norse Katanes ("headland of the cat"), and the Gaelic name for Sutherland, Cataibh, meaning "among the Cats".[110][111]

The location of "Thule", first mentioned by Pytheas of Massilia when he visited Britain sometime between 322 and 285 BC[112] is not known for certain. When Tacitus mentioned it in AD 98 it is clear he was referring to Shetland.[113]

| Island | Derivation | Language | Meaning | Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bressay | Breiðøy | Norse | broad island[114] | |

| Bruray | Norse | east isle[115] | Norse: bruarøy – "bridge island"[115] | |

| East Burra | Scots/Norse | east broch island[116] | ||

| Fair Isle | Frioarøy | Norse | fair island[117] | Norse: feoerøy – "far-off isle".[117] |

| Fetlar | Unknown | Pre-Celtic? | Unknown | Norse: fetill – "shoulder-straps"[118] or "fat land".[119] See also Funzie Girt. |

| Foula | Fugløy | Norse | bird island[120] | |

| Housay | Húsøy | Norse | house isle[115] | |

| Shetland Mainland | Hetlandensis | Norse/ Gaelic | island of the cat people?[110] | Perhaps originally from Gaelic: Innse Chat – see above[110] |

| Muckle Roe | Rauðey Milkla | Scots/Norse | big red island[116] | |

| Papa Stour | Papøy Stóra | Celtic/Norse | big island of the priests[121] | |

| Trondra | Norse | boar island[122] | Norse: "Þrondr's isle" or "Þraendir's isle". The first is a personal name, the second a tribal name from the Trondheim area.[122] | |

| Unst | Unknown | Pre-Celtic? | Unknown | Norse: omstr – "corn-stack"[118] or ørn-vist – "home of the eagle"[123] |

| Vaila | Valøy | Norse | falcon island[124] | Norse: "horse island", "battlefield island" or "round island"[124] |

| West Burra | Scots/Norse | west broch island[116] | ||

| Whalsay | Hvalsey | Norse | whale island[125] | |

| Yell | Unknown | Pre-Celtic? | Unknown | Norse: í Ála – "deep furrow"[118] or Jala – "white island"[126] |

Orkney

Pytheas described Great Britain as being triangular in shape, with a northern tip called Orcas.[112] This may have referred to Dunnet Head, from which Orkney is visible.[127] Writing in the 1st century AD, the Roman geographer Pomponius Mela called the Orkney islands Orcades, as did Tacitus in AD 98[127][128] "Orc" is usually interpreted as a Pictish tribal name meaning "young pig" or "young boar".[129] The old Irish Gaelic name for the islands was Insi Orc ("island of the pigs").[130][131][Note 2] The ogham script on the Buckquoy spindle-whorl is also cited as evidence for the pre-Norse existence of Old Irish in Orkney.[133] The Pictish association with Orkney is lent weight by the Norse name for the Pentland Firth – Pettaland-fjörðr i.e "Pictland Firth.[111]

The Norse retained the earlier root but changed the meaning, providing the only definite example of an adaption of a pre-Norse place name in the Northern Isles. The islands became Orkneyar meaning "seal islands".[134] An alternative name for Orkney is recorded in 1300—Hrossey, meaning "horse isle" and this may also contain a Pictish element of ros meaning "moor" or "plain".[107]

Unlike most of the larger Orkney islands, the derivation of the name "Shapinsay" is not obvious. The final 'ay' is from the Old Norse for island, but the first two syllables are more difficult to interpret. Haswell-Smith (2004) suggests the root may be hjalpandis-øy (helpful island) due to the presence of a good harbour, although anchorages are plentiful in the archipelago.[135] The first written record dates from 1375 in a reference to Scalpandisay, which may suggest a derivation from "judge's island". Another suggestion is "Hyalpandi's island", although no one of that name is known to have been associated with Shapinsay.[136]

| Island | Derivation | Language | Meaning | Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auskerry | Østr sker | Norse | east skerry[137] | |

| Burray | Borgrøy | Norse | broch island[138] | |

| Eday | Eidøy | Norse | isthmus island[139] | |

| Egilsay | Égillsey | Norse or Gaelic | Egil's island[140] | Possibly from Gaelic eaglais – church island[141] |

| Flotta | Flottøy | Norse | flat, grassy isle[142] | |

| Gairsay | Gáreksøy | Norse | Gárekr's isle[143] | |

| Graemsay | Grims-øy | Norse | Grim's island[144] | |

| Holm of Grimbister | Norse | Small and rounded islet of Grim's farm | ||

| Hoy | Háøy | Norse | high island[145] | |

| Inner Holm | English/Norse | inner rounded islet | ||

| North Ronaldsay | Rinansøy | Norse | Uncertain – possibly "Ringa's isle"[146] | |

| Orkney Mainland | Orcades | Various | isle(s) of the young pig[129] | See above |

| Papa Stronsay | Papey Minni | Norse | priest isle of Stronsay[147] | The Norse name is literally "little priest isle"[147] |

| Papa Westray | Papey Meiri | Norse | priest isle of Westray[148] | The Norse name is literally "big priest isle"[148] |

| Rousay | Hrólfsøy | Norse | Hrólfs island[149] | |

| Sanday | Sandøy | Norse | sand island[150] | |

| Shapinsay | Unknown | Possibly "helpful island"[135] | See above | |

| South Ronaldsay | Rognvaldsey | Norse | Rognvald's island[138] | |

| South Walls | Sooth Was | Scots/Norse | "southern voes" | "Voe" means fjord. Possibly "south bays". |

| Stronsay | Possibly Strjónsøy | Norse | good fishing and farming island[151] | |

| Westray | Vestrøy | Norse | western island[152] | |

| Wyre | Vigr | Norse | spear-like island[153] |

Uninhabited islands

Stroma, from the Norse Straumøy[154] means "current island"[155] or "island in the tidal stream",[154] a reference to the strong currents in the Pentland Firth. The Norse often gave animal names to islands and these have been transferred into English in, for example, the Calf of Flotta and Horse of Copinsay. Brother Isle is an anglicisation of the Norse breiðareøy meaning "broad beach island".[156] The Norse holmr, meaning "a small islet" has become "Holm" in English and there are numerous examples of this use including Corn Holm, Thieves Holm and Little Holm. "Muckle" meaning large or big is one of few Scots words in the island names of the Nordreyar and appears in Muckle Roe and Muckle Flugga in Shetland and Muckle Green Holm and Muckle Skerry in Orkney. Many small islets and skerries have Scots or Insular Scots names such as Da Skerries o da Rokness and Da Buddle Stane in Shetland, and Kirk Rocks in Orkney.

See also

References

- Notes

- Footnotes

- General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Clarence G Sinclair: Mell Head, Stroma, Pentland Firth" Archived 6 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Scotland's Places. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- "Northern Isles" Archived 11 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine. MSN Encarta. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 334, 502

- "Orkney Islands" Vision of Britain. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) p. 4

- "Visit Shetland". Visit.Shetland.org Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 336–403

- General Register Office for Scotland (2003)

- Marshall, J.E.A., & Hewett, A.J. "Devonian" in Evans, D., Graham C., Armour, A., & Bathurst, P. (eds) (2003) The Millennium Atlas: petroleum geology of the central and northern North Sea.

- Hall, Adrian and Brown, John (September 2005) "Basement Geology". Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- Odling, N.W.A. (2000) "Point of Ayre". (pdf) "Caledonian Igneous Rocks of Great Britain: Late Silurian and Devonian volcanic rocks of Scotland". Geological Conservation Review 17 : Chapter 9, p. 2731. JNCC. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- Hall, Adrian and Brown, John (September 2005) "Orkney Landscapes: Permian dykes" Archived 21 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- Brown, John Flett "Geology and Landscape" in Omand (2003) p. 10.

- Gillen (2003) pp. 90–91

- Keay & Keay (1994) p. 867

- Smith, David "Tsunami hazards". Fettes.com. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- Chalmers, Jim "Agriculture in Orkney Today" in Omand (2003) p. 129.

- "Shetland, Scotland Climate" climatetemp.info Retrieved 26 November 2010. Archived 15 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Shetland Islands Council (2005) pp. 5–9

- "Northern Scotland: climate" Archived 13 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Met office. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- "The Climate of Orkney" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- "Burradale Wind Farm Shetland Islands". REUK.co.uk. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- "About the Orkney Islands". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- "The Weather!". shetlandtourism.com. Retrieved 14 March 2011. Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- John Vetterlein (21 December 2006). "Sky Notes: Aurora Borealis Gallery". Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- "Heart of Neolithic Orkney" UNESCO. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- Wickham-Jones (2007) p. 40

- Armit (2006) pp. 31–33

- "The Knap of Howar" Archived 8 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine Orkney Archaeological Trust. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Turner (1998) p. 18

- Turner (1998) p. 26

- "Feltlar, Funziegirt" Archived 6 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine ScotlandsPlaces. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Fojut, Noel (1981) "Is Mousa a broch?" Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 111 pp. 220–228

- "From Chatham to Chester and Lincoln to the Lake District – 38 UK places put themselves forward for World Heritage status" (7 July 2010) Department for Culture, Media and Sport. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- "Sites make Unesco world heritage status bid shortlist" (22 March 2011) BBC Scotland. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- Hunter (2000) pp. 44, 49

- Wickham-Jones (2007) pp. 106–07

- Ritchie, Anna "The Picts" in Omand (2003) p. 39

- O'Dell, A. et al (December 1959) "The St Ninian's Isle Silver Hoard". Antiquity 33 No 132.

- O'Dell, A. St. Ninian's Isle Treasure. A Silver Hoard Discovered on St. Ninian's Isle, Zetland on 4th July, 1958. Aberdeen University Studies. No. 141.

- Wickham-Jones (2007) p. 108

- Ritchie, Anna "The Picts" in Omand (2003) p. 42

- Thomson (2008) p. 69. quoting the Orkneyinga Saga chapter 12.

- Schei (2006) pp. 11–12

- Thomson (2008) p. 24-27

- Watt, D.E.R., (ed.) (1969) Fasti Ecclesia Scoticanae Medii Aevii ad annum 1638. Scottish Records Society. p. 247

- Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) pp. 72–73

- Nicolson (1972) p. 44

- Nicolson (1972) p. 45

- Schei (2006) pp. 14–16

- Nicolson (1972) pp. 56–57

- "History". visit.shetland.org. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- "Ursula Smith" Shetlopedia. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- Schei (2006) pp. 16–17, 57

- "A History of Shetland" Visit.Shetland.org

- Thompson (2008) p. 183

- Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) pp. 78–79

- Thompson (2008) pp. 371–72

- Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 364–65

- Thomson, William P. L. "Agricultural Improvement" in Omand (2003) pp. 93, 99

- Coull, James "Fishing" in Omand (2003) pp. 144–55

- Troup, James A. "Stromness" in Omand (2003) p. 238

- Schei (2006) p. 16

- Nicolson (1972) pp. 91, 94–95

- Thomson (2008) pp. 434–36.

- Thomson (2008) pp. 439–43.

- "Shetlands-Larsen – Statue/monument" Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Kulturnett Hordaland. (Norwegian.) Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "The Shetland Bus" Archived 23 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine scotsatwar.org.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- "Alistair Carmichael: MP for Orkney and Shetland" alistaircarmichael.org.uk. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- "Candidates and Constituency Assessments". alba.org.uk – "The almanac of Scottish elections and politics". Retrieved 9 February 2010. Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Untouchable Orkney & Shetland Isles " (1 October 2009) www.snptacticalvoting.com Retrieved 9 February 2010. Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Highlands and Islands-Constituencies and members: Orkney Islands". Scottish Parliament. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- "Highlands and Islands-Constituencies and members: Shetland Islands". Scottish Parliament. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- "Social Work Inspection Agency: Performance Inspection Orkney Islands Council 2006. Chapter 2: Context." The Scottish Government. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- MacMahon, Peter and Walker, Helen (18 May 2007) "Winds of change sweep Scots town halls". Edinburgh. The Scotsman.

- "Political Groups" Shetland Islands Council. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- "Candidates and Constituency Assessments: Orkney (Highland Region)" alba.org.uk. Retrieved 11 January 2008. Archived 15 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Corporate information: About us". Serco NorthLink Ferries. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- "Travel: To Scotland: Orkney: Getting Here". Visit Scotland. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- "Ferries". Shetland.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- "Lighthouse Library" Northern Lighthouse Board. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- "Sumburgh Airport" Highlands and Islands Airports. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- "UK Airport Statistics: 2005 – Annual" Archived 11 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine Table 10: EU and Other International Terminal Passenger Comparison with Previous Year. (pdf) CAA. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- "Getting Here" Westray and Papa Westray Craft and Tourist Associations. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- "Economy". move.shetland.org Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- "Asset Portfolio: Sullom Voe Termonal" (pdf) BP. Retrieved 19 March 2011. Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) p. 13

- "Shetland's Economy". Visit.Shetland.org. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Shetland Islands Council (2005) p. 13

- "Public Sector". move.shetland.org. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) pp. 16–17

- Chalmers, Jim "Agriculture in Orkney Today" in Omand (2003) p. 127, 133 quoting the Scottish Executive Agricultural Census of 2001 and stating that 80% of the land area is farmed if rough grazing is included.

- "Orkney Economic Review No. 23." (2008) Kirkwall. Orkney Islands Council.

- "European Marine Energy Centre". Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- "Pelamis wave energy project Information sheet" Archived 15 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. (pdf) E.ON Climate and Renewables UK Ltd. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- "Underwater data centre installed on the seabed off Orkney". The Orcardian. 6 June 2018. Archived from the original on 8 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "The Trows". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- Muir, Tom "Customs and Traditions" in Omand (2003) p. 270

- Drever, David "Orkney Literature" in Omand (2003) p. 257

- "The Forty Fiddlers" Shetlopedia. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- Culshaw, Peter (18 June 2006) " The Tale of Thomas Fraser" guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "Insular Scots". Scots Language Centre. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Glanville Price, The Languages of Britain (London: Edward Arnold 1984, ISBN 978-0-7131-6452-7), p. 203

- McColl Millar. 2007. Northern and Insular Scots. Edinburgh: University Press Ltd. p.5

- Gammeltoft (2010) p. 21

- Sandnes (2010) p. 9

- Gammeltoft (2010) p. 22

- Gammeltoft (2010) p. 9

- Watson (1994) p. 30

- Breeze, David J. "The ancient geography of Scotland" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 11–13

- Watson (1994) p. 7

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 425

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 459

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 433

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 408

- Gammeltoft (2010) pp. 19–20

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 471

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 419

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 449

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 434

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 481

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 430

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 452

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 467

- "Early Historical References to Orkney" Orkneyjar.com. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- Tacitus (c. 98) Agricola. Chapter 10. "ac simul incognitas ad id tempus insulas, quas Orcadas vocant, invenit domuitque".

- Waugh, Doreen J. "Orkney Place-names" in Omand (2003) p. 116

- Pokorny, Julius (1959) Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- "The Origin of Orkney" Orkneyjar.com. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- "Proto-Celtic – English Word List" (pdf) (12 June 2002) University of Wales. p. 101

- Forsyth, Katherine (1995). "The ogham-inscribed spindle-whorl from Buckquoy: evidence for the Irish language in pre-Viking Orkney?". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. ARCHway. 125: 677–96. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- Gammeltoft (2010) pp. 8–9

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 364

- "Orkney Placenames" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 363

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 354

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 386

- Gammeltoft (2010) p. 16

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 379

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 341

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 367

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 352

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 343

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 400

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 376

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 397

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 383

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 392

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 370

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 394

- Gammeltoft (2010) p. 18

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 336

- Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 109

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 465

- General references

- Armit, Ian (2006) Scotland's Hidden History. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3764-X

- Ballin Smith, B. and Banks, I. (eds) (2002) In the Shadow of the Brochs, the Iron Age in Scotland. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2517-X

- Clarkson, Tim (2008) The Picts: A History. Stroud. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4392-8

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Gammeltoft, Peder (2010) "Shetland and Orkney Island-Names – A Dynamic Group". Northern Lights, Northern Words. Selected Papers from the FRLSU Conference, Kirkwall 2009, edited by Robert McColl Millar.

- General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- Gillen, Con (2003) Geology and landscapes of Scotland. Harpenden. Terra Publishing. ISBN 1-903544-09-2

- Keay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255082-2

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Omand, Donald (ed.) (2003) The Orkney Book. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-254-9

- Nicolson, James R. (1972) Shetland. Newton Abbott. David & Charles.

- Sandnes, Berit (2003) From Starafjall to Starling Hill: An investigation of the formation and development of Old Norse place-names in Orkney. (pdf) Doctoral Dissertation, NTU Trondheim.

- Sandnes, Berit (2010) "Linguistic patterns in the place-names of Norway and the Northern Isles" Northern Lights, Northern Words. Selected Papers from the FRLSU Conference, Kirkwall 2009, edited by Robert McColl Millar.

- Schei, Liv Kjørsvik (2006) The Shetland Isles. Grantown-on-Spey. Colin Baxter Photography. ISBN 978-1-84107-330-9

- Shetland Islands Council (2010) "Shetland in Statistics 2010" (pdf) Economic Development Unit. Lerwick. Retrieved 6 March 2011

- Thomson, William P. L. (2008) The New History of Orkney Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-696-0

- Turner, Val (1998) Ancient Shetland. London. B. T. Batsford/Historic Scotland. ISBN 0-7134-8000-9

- Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2007) Orkney: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-596-3

- Watson, W. J. (1994) The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-323-5. First published 1926.