Transport in the United Kingdom

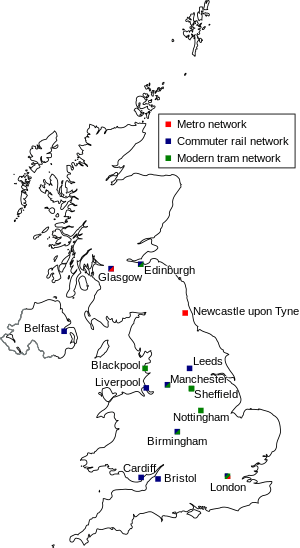

Transport in the United Kingdom is facilitated with road, air, rail, and water networks. A radial road network totals 29,145 miles (46,904 km) of main roads, 2,173 miles (3,497 km) of motorways and 213,750 miles (344,000 km) of paved roads. The National Rail network of 10,072 route miles (16,116 km) in Great Britain and 189 route miles (303 route km) in Northern Ireland carries over 18,000 passenger and 1,000 freight trains daily. Urban rail networks exist in Belfast, Birmingham, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Liverpool, London, Manchester and Newcastle. There are many regional and international airports, with Heathrow Airport in London being one of the busiest in the world.[1] The UK also has a network of ports which received over 558 million tons of goods in 2003–2004. Transport is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions by the United Kingdom.

Transport trends

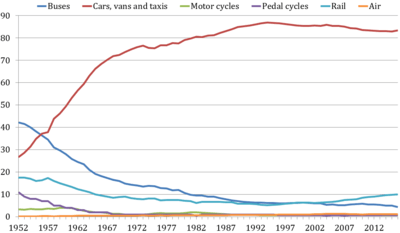

Since 1952 (the earliest date for which comparable figures are available), the United Kingdom saw a growth of car use, which increased its modal share, while the use of buses declined, and railway use has grown more slowly.[3][4] However, since the 1990s, rail has started increasing its modal share at the expense of cars, increasing from 5% to 10% of passenger-kilometres travelled.[2] This coincided with the privatisation of British Rail, but its impact is heavily debated.

In 1952, 27% of distance travelled was by car or taxi; with 42% being by bus or coach and 18% by rail. A further 11% was by bicycle and 3% by motorcycle. The distance travelled by air was negligible.

By 2015 83% of distance travelled was by car or taxi; with 5% being by bus and 10% by rail. Air, pedal cycle and motorcycle accounted for roughly 1% each.[2] In terms of passenger-kilometres, slightly over 662 billion were made by cars, motorcycles vans and taxis, 78 billion by rail, 39 billion by bus, 5 billion by pedal cycle and 9 billion on domestic air flights.[2]

Passenger transport has grown in recent years. Figures from the DfT show that total passenger travel inside the United Kingdom has risen from 403 billion passenger kilometres in 1970 to 793 billion in 2015.[2]

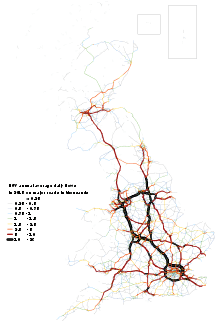

Freight transport has undergone similar changes, increasing in volume and shifting from railways onto the road. In 1953 89 billion tonne kilometres of goods were moved, with rail accounting for 42%, road 36% and water 22%. By 2010 the volume of freight moved had more than doubled to 222 billion tonne kilometres, of which 9% was moved by rail, 19% by water, 5% by pipeline and 68% by road.[5] Despite the growth in tonne kilometres, the environmental external costs of trucks and lorries in the UK have reportedly decreased. Between 1990 and 2000, there has been a move to heavier goods vehicles due to major changes in the haulage industry including a shift in sales to larger articulated vehicles. A larger than average fleet turnover has ensured a swift introduction of new and cleaner vehicles in the UK.[6]

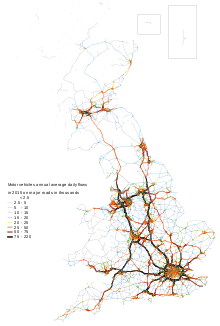

Although the decline in railway use led to a reduction in the length of the rail network, the length of the road network has not increased in proportion to the increase in road use. Whereas the rail network has halved from 19,471 mi (31,336 km) in 1950 to 10,014 mi (16,116 km) today, the major road network only increased from 44,710 mi (71,950 km) in 1951 to 50,893 mi (81,904 km) in 1990, and reduced slightly to 50,265 mi (80,894 km) by 2010. In 2008, the Department for Transport stated that traffic congestion is one of the most serious transport problems facing the United Kingdom.[7] According to the government-sponsored Eddington report of 2006, bottleneck roads are in serious danger of becoming so congested that it may damage the economy.[8]

Air transport

There are 471 airports and airfields in the UK, of which 334 are paved. There are also 11 heliports. (2004 CIA estimates)

Heathrow Airport is the largest airport by traffic volume in the UK, is owned by Heathrow Airport Holdings, and is one of the world's busiest airports. Gatwick Airport, the second largest, and is owned by Global Infrastructure Partners. The third largest is Manchester Airport, in Manchester, which is run by Manchester Airport Group, which also owns various other airports.

Other major airports include Stansted Airport in Essex and Luton Airport in Bedfordshire, both about 30 miles (48 km) north of London, Birmingham Airport in Solihull, Newcastle Airport, Liverpool Airport, and Bristol Airport.

Outside England, Cardiff, Edinburgh and Belfast, are the busiest airports serving Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland respectively.

The largest airline in the United Kingdom by passenger traffic is easyJet, whereas British Airways is largest by fleet size and international destinations. Others include Jet2, TUI Airways and Virgin Atlantic.

Rail transport

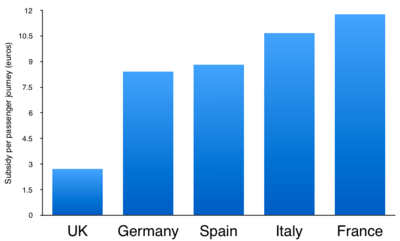

The rail network in the United Kingdom consists of two independent parts, that of Northern Ireland and that of Great Britain. Since 1994, the latter has been connected to mainland Europe via the Channel Tunnel. The network of Northern Ireland is connected to that of the Republic of Ireland. The National Rail network of 10,072 miles (16,209 km) in Great Britain and 189 route miles (303 route km) in Northern Ireland carries 1.7 billion passengers and 110 million tonnes of freight annually.[9][10] Urban rail networks are also well developed in London and several other cities. There were once over 30,000 miles (48,000 km) of rail network in the UK; however, most of this was reduced over a time period from 1955 to 1975, much of it after a report by a government advisor Richard Beeching in the mid-1960s (known as the Beeching cuts). The UK was ranked eighth among national European rail systems in the 2017 European Railway Performance Index assessing intensity of use, quality of service and safety.[11] While the rail system in the UK had an excellent rating for safety, its rating for intensity of use was only good, owing to a low level of freight utilization, and its quality of service was rated poor because of high fares and the relatively low punctuality of regional trains.[11]

Great Britain

The rail network in Great Britain is the oldest such network in the world. The system consists of five high-speed main lines (the West Coast, East Coast, Midland, Great Western and Great Eastern), which radiate from London to the rest of the country, augmented by regional rail lines and dense commuter networks within the major cities. High Speed 1 is operationally separate from the rest of the network, and is built to the same standard as the TGV system in France.

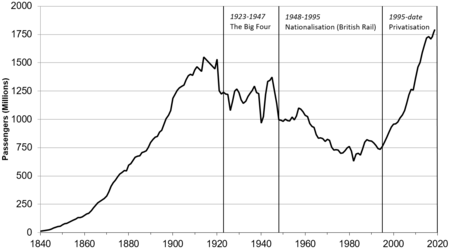

The world's first passenger railway running on steam was the Stockton and Darlington Railway, opened on 27 September 1825. Just under five years later the world's first intercity railway was the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, designed by George Stephenson and opened by the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington on 15 September 1830. The network grew rapidly as a patchwork of literally hundreds of separate companies during the Victorian era, which eventually was consolidated into just four by 1922, as the boom in railways ended and they began to lose money. Eventually, the entire system came under state control in 1948, under the British Transport Commission's Railway Executive. After 1962 it came under the control of the British Railways Board; then British Railways (later British Rail), and the network was reduced to less than half of its original size by the infamous Beeching cuts of the 1960s when many unprofitable branch lines were closed. Several stations have been reopened in Wales.

In 1994 and 1995, British Rail was split into infrastructure, maintenance, rolling stock, passenger and freight companies, which were privatised from 1996 to 1997. The privatisation has delivered very mixed results, with healthy passenger growth, mass refurbishment of infrastructure, investment in new rolling stock, and safety improvements being offset by concerns over network capacity and the overall cost to the taxpayer, which has increased due to growth in passenger numbers. It has also led to some confusion as to who looks after different aspects of the rail service among the general public. This is because, for example, different companies run the tracks to those that run the trains and locomotives. Since privatisation, passenger levels have more than doubled and have surpassed the level they had been at in the late 1940s. But while the price of anytime and off-peak tickets has increased, the price of Advance tickets has dramatically decreased in real terms: the average Advance ticket in 1995 cost £9.14 (in 2014 prices) compared to £5.17 in 2014.[18] Subsidies to the rail industry have slightly increased from £3.7bn in 1992–93 to £3.9bn in 2012–13 (in 2013 prices) but more than halved in terms of subsidy per journey from £4.98 to £2.46.[19]

In Britain, the infrastructure (track, stations, depots and signalling chiefly) is owned and maintained by Network Rail, a not-for-profit company. Network Rail replaced Railtrack, which became bankrupt in 2002 following the Hatfield rail crash in 2000. Passenger services are operated by train-operating companies (TOCs), which are franchises awarded by the United Kingdom Government or the Scottish government. Examples include Avanti West Coast and East Midlands Railway. Freight trains are operated by freight operating companies, such as DB Cargo UK, which are commercial operations unsupported by the government. Most train operating companies do not own the locomotives and coaches that they use to operate passenger services. Instead, they are required to lease these from the three rolling stock companies (ROSCOs), with train maintenance carried out by companies such as Bombardier and Alstom.

In Great Britain there are 10,274 miles (16,534 km) of 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) gauge track, reduced from a historic peak of over 30,000 miles (48,000 km). Of this, 3,062 miles (4,928 km) is electrified and 7,823 miles (12,590 km) is double or multiple tracks. The maximum scheduled speed on the regular network has historically been around 125 miles per hour (201 km/h) on the InterCity lines. On High Speed 1, trains are now able to reach the speeds of French TGVs.

A High Speed 2 line running north from London has been proposed and the legislation needed for the first phase is (as of May 2014) proceeding through parliament. Network Rail are considering reopening a railway in south-west England connecting Tavistock to Okehampton and Exeter as an alternative to the coastal mainline which was damaged at Dawlish by coastal storms in February 2014, causing widespread disruption.[20]

To cope with increasing passenger numbers, there is a large ongoing programme of upgrades to the network, including Thameslink, Crossrail, electrification of lines, in-cab signalling, new inter-city trains and a new high-speed line.

The Office of Rail & Road (ORR) is the regulator for Network Rail, they are currently overseeing funding for Control Period 6 (CP6) – from 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2024.

Northern Ireland

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1503708.jpg)

In Northern Ireland, Northern Ireland Railways (NIR) both owns the infrastructure and operates passenger rail services. The Northern Ireland rail network is one of the few networks in Europe that carry no freight. It is publicly owned. NIR was united in 1996 with Northern Ireland's two publicly owned bus operators – Ulsterbus and Metro (formally Citybus) – under the brand Translink.

In Northern Ireland there is 212 miles (341 km) of track at 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in) gauge. 118 miles (190 km) of it is double track.

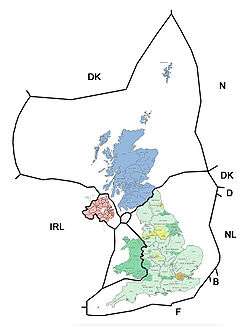

International rail services

Eurostar operates trains via the Channel Tunnel to France and Belgium and the joint Northern Ireland Railways/Iarnród Éireann Enterprise trains link Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland as well as one Iarnród Éireann train per weekday in the morning from Dublin to Newry.

Rapid transit

Three cities in the United Kingdom have rapid transit systems. The most well known is the London Underground (commonly known as the Tube), the oldest rapid transit system in the world (opened 1863). Another system also in London is the separate Docklands Light Railway (opened 1987). Although this is more of an elevated light metro system due to its lower passenger capacities; further, it is integrated with the Underground in many ways). Outside London, there is the Glasgow Subway which is the third oldest rapid transit system in the world (opened 1896). One other system, the Tyne & Wear Metro (opened 1980), serves Newcastle, Gateshead, Sunderland, North Tyneside and South Tyneside, and has many similarities to a rapid transit system including underground stations, but is sometimes considered to be light rail.[21]

Urban rail

Urban commuter rail networks are focused on many of the country's major cities:

- Belfast – Belfast Suburban Rail

- Birmingham – West Midlands Railway

- Bristol – Great Western Railway and proposed MetroWest

- Cardiff – Valley Lines including proposed South Wales Metro

- Edinburgh – Abellio ScotRail

- Glasgow – Abellio ScotRail

- Leeds – MetroTrain

- Liverpool – Merseyrail

- London – London Underground and London Overground (with Crossrail under construction)

- Manchester – Northern and TransPennine Express

- Newcastle – Tyne & Wear Metro

They consist of several railway lines connecting city centre stations of major cities to suburbs and surrounding towns. Train services and ticketing are fully integrated with the national rail network and are not considered separate.

In London, a route for Crossrail 2 has been safeguarded.

Trams and light rail

Tram systems were popular in the United Kingdom in the late 19th and early 20th century. However, with the rise of the car they began to be widely dismantled in the 1950s. By 1962 only the Blackpool tramway and the Glasgow Corporation Tramways remained; the final Glasgow service was withdrawn on 2 September 1962. Recent years have seen a revival the United Kingdom, as in other countries, of trams together with light rail systems.

| Primary location |

System | Date opened |

Line(s) | Stations | System length |

Passenger Revenue |

Passengers (2018/19)[22] |

Change from previous year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blackpool | Blackpool Tramway | 1885 | 1 | 38 | 17 km | £6.8m | 5.2 m | |

| Newcastle / Tyne & Wear | Tyne & Wear Metro | 1980 | 2 | 60 | 74 km | £51.9m | 36.4 m | |

| London | Docklands Light Railway | 1987 | 7 | 45 | 34 km | £176.5m | 119.6 m | |

| Greater Manchester | Manchester Metrolink | 1992 | 8 | 99 | 105 km | £82.1m | 41.2 m | |

| Sheffield | Sheffield Supertram | 1994 | 4 | 50 | 34 km | £14.0m | 11.9m | |

| West Midlands | West Midlands Metro | 1999 | 1 | 26 | 21 km | £10.7m | 5.9m | |

| London | Tramlink | 2000 | 4 | 39 | 28 km | £23.5m | 28.7m | |

| Nottingham | Nottingham Express Transit | 2004 | 2 | 51 | 32 km | £20.6m | 18.8m | |

| Edinburgh | Edinburgh Trams | 2014 | 1 | 16 | 14 km | £5.4 m[23] | 15.7m[24] |

Road transport

The road network in Great Britain, in 2006, consisted of 7,596 miles (12,225 km) of trunk roads (including 2,176 miles (3,502 km) of motorway), 23,658 miles (38,074 km) of principal roads (including 34 miles (55 km) of motorway), 71,244 miles (114,656 km) of "B" and "C" roads, and 145,017 miles (233,382 km) of unclassified roads (mainly local streets and access roads) – totalling 247,523 miles (398,350 km).[25][26]

Road is the most popular method of transport in the United Kingdom, carrying over 90% of motorised passenger travel and 65% of domestic freight.[26] The major motorways and trunk roads, many of which are dual carriageway, form the trunk network which links all cities and major towns. These carry about one third of the nation's traffic, and occupy about 0.16% of its land area.[26]

The motorway system, which was constructed from the 1950s onwards, is stated by the British Chambers of Commerce to be, by virtually every measurement of motorway capacity, well below the capacity of other leading European nations,[27] They give comparative figures for a selection of nations of (units = km/million population): United Kingdom 60, Luxembourg 280, Spain 225, Austria 200, France 185, Belgium 165, Denmark 165, Sweden 165, Netherlands 140, Germany 140, Italy 115, Finland 100, Portugal 80, Greece 45 and Ireland 30.[27] although many other roads are of near motorway standard.

Highways England (a government-owned company) is responsible for maintaining motorways and trunk roads in England. Other English roads are maintained by local authorities. In Scotland and Wales roads are the responsibility of Transport Scotland, an Executive Agency of the Scottish government, and the Welsh Government respectively.[28] Northern Ireland's roads are overseen by the Roads Service Northern Ireland, a section of the Department for Regional Development.[28][29] In London, Transport for London is responsible for all trunk roads and other major roads, which are part of the Transport for London Road Network.[28]

Toll roads are rare in the United Kingdom, though there are a number of toll bridges. Road traffic congestion has been identified as a key concern for the future prosperity of the United Kingdom, and policies and measures are being investigated and developed by the government to reduce congestion.[7] In 2003, the United Kingdom's first toll motorway, the M6 Toll, opened in the West Midlands area to relieve the congested M6 motorway.[30] Rod Eddington, in his 2006 report Transport's role in sustaining the UK's productivity and competitiveness, recommended that the congestion problem should be tackled with a "sophisticated policy mix" of congestion-targeted road pricing and improving the capacity and performance of the transport network through infrastructure investment and better use of the existing network.[4][31] Congestion charging systems do operate in the cities of London[32] and Durham[33] and on the Dartford Crossing. In 2005, the Government published proposals for a United Kingdom-wide road pricing scheme. This was designed to be revenue neutral with other motoring taxes to be reduced to compensate.[34] The plans were extremely controversial; 1.8 million people signed a petition against them.[35]

Driving is on the left.[36] The usual maximum speed limit is 70 miles per hour (112 km/h) on motorways and dual carriageways.[37]

On 29 April 2015, the UK Supreme Court ruled that the government must take immediate action to cut air pollution,[38] following a case brought by environmental lawyers at ClientEarth.[39]

Segregated bicycle paths

These are being installed in some cities in the UK such as London, Glasgow, Manchester, Bristol, Cardiff for example. In London Transport for London has installed Cycleways.[40]

Cycle lanes

The National Cycle Network, created by the charity Sustrans, is the UK's major network of signed routes for cycling. It uses dedicated bike paths as well as roads with minimal traffic, and covers 14,000 miles, passing within a mile of half of all homes.[41] Other cycling routes such as The National Byway, the Sea to Sea Cycle Route and local cycleways can be found across the country.

Road passenger transport

Buses

Local bus services cover the whole country. Since deregulation the majority (80% by the late 1990s[42]) of these local bus companies have been taken over by one of the "Big Five" private transport companies: Arriva, FirstGroup, Go-Ahead Group, National Express and Stagecoach Group. In Northern Ireland coach, bus (and rail) services remain state-owned and are provided by Translink.

Coaches

Coaches provide long-distance links throughout the UK: in England and Wales the majority of coach services are provided by National Express. Flixbus and Megabus run no-frills coach services in competition with National Express, the latter's services in Scotland are operated in co-operation with Scottish Citylink. BlaBlaBus also operate to France and the Low Countries from London.

Road freight transport

In 2014, there were around 285,000 HGV drivers in the UK and in 2013 the trucking industry moved 1.6 billion tonnes of goods, generating £22.9 billion in revenue.[43]

Water transport

Due to the United Kingdom's island location, before the Channel Tunnel the only way to enter or leave the country (apart from air travel) was on water, except at the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Ports and harbours

About 95% of freight enters the United Kingdom by sea (75% by value). Three major ports handle the most freight traffic:

- Grimsby & Immingham on the east coast.[44]

- Port of London, on the River Thames.[44]

- Milford Haven, in south-west Wales.[44]

There are many other ports and harbours around the United Kingdom, including the following:

Aberdeen, Avonmouth, Barrow, Barry, Belfast, Boston, Bristol, Cairnryan, Cardiff, Dover, Edinburgh/Leith, Falmouth, Felixstowe, Fishguard, Glasgow, Gloucester, Grangemouth, Grimsby, Harwich, Heysham, Holyhead, Hull, Kirkwall, Larne, Liverpool, Londonderry, Manchester, Oban, Peterhead, Plymouth, Poole, Port Talbot, Portishead, Portsmouth, Scapa Flow, Southampton, Stornoway, Stranraer, Sullom Voe, Swansea, Tees (Middlesbrough), Tyne (Newcastle).

Merchant marine

For long periods of recent history, Britain had the largest registered merchant fleet in the world, but it has slipped down the rankings partly due to the use of flags of convenience. There are 429 ships of 1,000 gross tonnage (GT) or over, making a total of 9,181,284 GT (9,566,275 tonnes deadweight (DWT)). These are split into the following types: bulk carrier 18, cargo ship 55, chemical tanker 48, container ship 134, liquefied gas 11, passenger ship 12, passenger/cargo ship 64, petroleum tanker 40, refrigerated cargo ship 19, roll-on/roll-off 25, vehicle carrier 3. There are also 446 ships registered in other countries, and 202 foreign-owned ships registered in the United Kingdom. (2005 CIA)

Ferries

Ferries, both passenger only and passengers and vehicles, operate within the United Kingdom across rivers and stretches of water. In east London the Woolwich Ferry links the North and South Circular Roads. Gosport and Portsmouth are linked by the Gosport Ferry; Southampton and Isle of Wight are linked by ferry and fast Catamaran ferries; North Shields and South Shields on Tyneside are linked by the Shields Ferry; and the Mersey has the Mersey Ferry.

In Scotland, Caledonian MacBrayne provides passenger and RO-RO ferry services in the Firth of Clyde, to various islands of the Inner and Outer Hebrides from Oban and other ports. Orkney Ferries provides services within the Orkney Isles; and NorthLink Ferries provides services from the Scottish mainland to Orkney and Shetland, mainly from Aberdeen although other ports are also used. Ferries operate to Northern Ireland from Stranraer and Cairnryan to Larne and Belfast.

Holyhead, Pembroke Dock and Fishguard are the principal ports for ferries between Wales and Ireland. Heysham and Liverpool/Birkenhead have ferry services to the Isle of Man.

Passenger ferries operate internationally to nearby countries such as France, the Republic of Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Spain. Ferries usually originate from one of the following:

- Dover with services to Calais operated by P&O Ferries, My Ferry Link and DFDS Seaways.

- Portsmouth International Port is the main hub for longer services on the Western Channel to Ouistreham, Le Havre, Cherbourg and Saint Malo in France, and Santander and Bilbao in Spain. Most services are operated by French company Brittany Ferries with some to Cherbourg and Le Havre by Condor Ferries and DFDS Seaways.

- Services from Plymouth operate to Santander (Spain) and Roscoff (France) with Brittany Ferries.

- Services from Weymouth and Poole operate to the Channel Islands with Condor Ferries and to Cherbourg (from Poole) with Brittany Ferries.

- Holyhead is the principal ferry port for services to Ireland, operated by Irish Ferries and Stena Line with some services originating from Pembroke.

- Hull and Harwich are the main hubs for services to the Netherlands.

More services from Ramsgate, Newhaven, Southampton, and Lymington operate to France, Belgium and the Isle of Wight.

Waterbuses operate on rivers in some of the country's largest cities such as London (London River Services and Thames Clippers), Cardiff (Cardiff Waterbus) and Bristol (Bristol Ferry Boat).

Other shipping

Cruise ships depart from the United Kingdom for destinations worldwide, many heading for ports around the Mediterranean and Caribbean. The Cunard Line still offer a scheduled transatlantic service between Southampton and New York City with RMS Queen Mary 2. The Solent is a world centre for yachting and home to largest number of private yachts in the world.

Inland waterways

Major canal building began in the United Kingdom after the onset of the Industrial revolution in the 18th century. A large canal network was built and it became the primary method of transporting goods throughout the country; however, by the 1830s with the development of the railways, the canal network began to go into decline.

There are currently 1,988 miles (3,199 km) of waterways in the United Kingdom and the primary use is recreational. 385 miles (620 km) is used for commerce. (2004 CIA estimate)

Education and professional development

The United Kingdom also has a well-developed network of organisations offering education and professional development in the transport and logistics sectors.

Educational organisations

A number of Universities offer degree programmes in transport, usually covering transport planning, engineering of transport infrastructure, and management of transport and logistics services. The Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds is one such organisation.

Professional development

Professional development for those working in the transport and logistics sectors is provided by a number of Professional Institutes representing specific sectors. These include:

- Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport (CILT(UK))

- Chartered Institution of Highways and Transportation (CIHT)

- Institution of Railway Operators

- Transport Planning Society (TPS)

Through these professional bodies, transport planners and engineers can train for a number of professional qualifications, including:

- Chartered engineer

- Incorporated engineer

- Transport planning professional

See also

- Air transport of the Royal Family and government of the United Kingdom

- Royal Train

- Transport Direct

- Transport in the Republic of Ireland

- United Kingdom

- Climate Change Act 2008

References

- "Where Are the 30 Busiest Airports in the World?". Geography.about.com.

- "Department for Transport Statistics: Passenger transport: by mode, annual from 1952".

- "EU Transport in Figures; Statistical Pocketbook". European Commission Directorate-General for Energy and Transport; Eurostat. 2007. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008.

- Rod Eddington (December 2006). "The Eddington Transport Study". UK Treasury.

- "Department for Transport statistics" (PDF). Gov.uk.

- L. Int Panis; P. Waktiss; L. De Nocker; R. Torfs (October 2000). "A comparative analysis of trends in environmental externalities of road transport (1990–2010) in Belgium and the UK". TERA2K.

- "Tackling congestion on our roads". Department for Transport. Archived from the original on 23 April 2008.

- "Delivering choice and reliability". Department for Transport. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008.

- "Previous statistical releases | Office of Rail and Road". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 5 June 2018.

- "Railway Statistics – 2014 Synopsis" (PDF). Paris, France: UIC (International Union of Railways). 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- "the 2017 European Railway Performance Index". Boston Consulting Group.

- "German Railway Financing" (PDF). Deutschebahn.com.

- "Efficiency indicators of Railways in France" (PDF). Internationaltransportforum.org.

- "Rail industry financial information 2014-15" (PDF). Orr.gov.uk.

- "ORR report" (PDF). Orr.gov.uk.

- "Spanish rail subsidies". Railway-technology.com.

- "Public subsidies and transfers to Italian transport sector" (PDF). Sipotra.it. pp. 5 & 10.

- "How do fares here compare with the rest of Europe?". Raildeliverygroup.com.

- "Have train fares gone up or down since British Rail?". Bbc.co.uk. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "Network Rail chooses Dawlish alternative route". BBC News. 10 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Michael Taplin (March 2013). "Home – World Systems List index – World List U-Z – United Kingdom (GB)". Light Rail Transit Association (LRTA). Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- "Light Rail and Tram Statistics - England 2018-19" (PDF). Department for Transport. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Edinburgh trams carry 5.38m passengers in a year". BBC News. 6 June 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- "Annual passenger revenue of Edinburgh Trams in the United Kingdom (UK) from 2014/15 to 2018/19". statista.com. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Transport Statistics Great Britain: 2007 Edition". UK Department for Transport. September 2007. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Banks, Bayliss and Glaister (December 2007). "Motoring towards 2050: Roads and Reality". RAC Foundation. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The ROAD to SUCCESS?: Transport Manifesto 2004". The British Chambers of Commerce. 2004. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "How roads are managed in the UK". Department for Transport. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- "What We Do". Roads Service Northern Ireland. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- "M6 Toll (formerly Birmingham Northern Relief Road)". The Motorway Archive. The Motorway Archive Trust. Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- Rod Eddington (December 2006). "Speech by Rod Eddington to the Commonwealth Club in London on 1 December 2006". Department for Transport. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008.

- "Smooth start for congestion charge". BBC News. 18 February 2003. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- "Toll road lawyers in award hope". BBC News. 9 April 2006. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- "'Pay-as-you-go' road charge plan". BBC News. 6 June 2005. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- "PM denies road toll 'stealth tax'". BBC News. 21 February 2007. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- "159–161: General rules". The Highway Code. HMSO. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- "117–126: Control of the vehicle". The Highway Code. HMSO. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- "Court orders UK to cut NO2 air pollution". BBC News. BBC. 29 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- "UK Supreme Court orders Government to take "immediate action" on air pollution". ClientEarth. 29 April 2015. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- Matters, Transport for London | Every Journey. "Cycleways". Transport for London.

- "About the National Cycle Network". Sustrans.org.uk. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "Department for Transport – GOV.UK" (PDF). Dft.gov.uk.

- Williams, Francesca (17 June 2015). "Lorry driving: The logistics of keeping logistics on the road". Bbc.co.uk.

- "Statistical data set PORT01 – UK ports and traffic". Department for Transport.

![]()