British Sign Language

British Sign Language (BSL) is a sign language used in the United Kingdom (UK), and is the first or preferred language of some deaf people in the UK. There are 125,000[5] deaf adults in the UK who use BSL, plus an estimated 20,000 children. In 2011, 15,000 people living in England and Wales reported themselves using BSL as their main language.[6] The language makes use of space and involves movement of the hands, body, face, and head. Many thousands of people who are not deaf also use BSL, as hearing relatives of deaf people, sign language interpreters or as a result of other contact with the British deaf community.

| British Sign Language (BSL) | |

|---|---|

| Breetish Sign Leid Iaith Arwyddion Prydain Cànan Soidhnidh Bhreatainn Teanga Comhartha na Breataine | |

| |

| Native to | United Kingdom |

Native speakers | 77,000 (2014)[1] 250,000 L2 speakers (2013) |

BANZSL

| |

| none widely accepted SignWriting[2] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Scotland,[3] England, European Union |

Recognised minority language in | Wales |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | bfi |

| Glottolog | brit1235[4] |

History

| BANZSL family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History records the existence of a sign language within deaf communities in England as far back as 1570. British Sign Language has evolved, as all languages do, from these origins by modification, invention and importation.[7][8] Thomas Braidwood, an Edinburgh teacher, founded 'Braidwood's Academy for the Deaf and Dumb' in 1760 which is recognised as the first school for the deaf in Britain. His pupils were the sons of the well-to-do. His early use of a form of sign language, the combined system, was the first codification of what was to become British Sign Language. Joseph Watson was trained as a teacher of the deaf under Thomas Braidwood and he eventually left in 1792 to become the headmaster of the first public school for the deaf in Britain, the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb in Bermondsey.

In 1815, an American Protestant minister, Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, travelled to Europe to research teaching of the deaf. He was rebuffed by both the Braidwood schools who refused to teach him their methods. Gallaudet then travelled to Paris and learned the educational methods of the French Royal Institution for the Deaf, a combination of Old French Sign Language and the signs developed by Abbé de l’Épée. As a consequence American Sign Language today has a 60% similarity to modern French Sign Language and is almost unintelligible to users of British Sign Language.

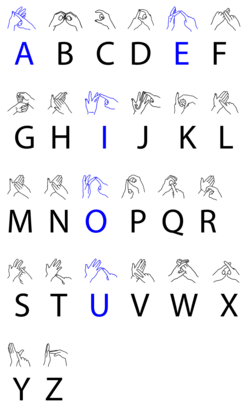

Until the 1940s sign language skills were passed on unofficially between deaf people often living in residential institutions. Signing was actively discouraged in schools by punishment and the emphasis in education was on forcing deaf children to learn to lip read and finger spell. From the 1970s there has been an increasing tolerance and instruction in BSL in schools. The language continues to evolve as older signs such as alms and pawnbroker have fallen out of use and new signs such as internet and laser have been coined. The evolution of the language and its changing level of acceptance means that older users tend to rely on finger spelling while younger ones make use of a wider range of signs.[9]

On 18 March 2003 the UK government formally recognised that BSL is a language in its own right.[10]

Linguistics

Linguistics are an integral component to any language because this allows for languages to be understood in a more efficient manner when taught.[11] In general, sign languages have their own 'words' (hand gestures) that could not be understood in other dialects.[11] How one language signs a certain number would be different than how another language signs it.[11] British Sign Language is described as a 'spatial language' as it "moves signs in space.[11]"

Phonology

Like many other sign languages, BSL phonology is defined by elements such as handshape, orientation, location, movement, and non-manual features. There are phonological components to sign language that have no meaning alone but work together to create a meaning of a signed word: hand shape, movement, location, orientation and facial expression.[12][11] The meanings of words differ if one of these components is changed.[12][11] Signs can be identical in certain components but different in others, giving each a different meaning.[11] Facial expression falls under the 'non-manual features' component of phonology.[13] These include "eyebrow height, eye gaze, mouthing, head movement, and torso rotation.[13]"

Grammar

In common with other languages, whether spoken or signed, BSL has its own grammar which govern how phrases are signed.[11] BSL has a particular syntax.[11] One important component of BSL is its use of proforms.[11] A proform is “...any form that stands in the place of, or does the job of, some other form."[11] Sentences are composed of two parts, in order: the subject and the predicate.[11] The subject is the topic of the sentence, while the predicate is the commentary about the subject.[11]

BSL uses a topic–comment structure.[14] Topic-comment means that the topic of the signed conversation is first established, followed by an elaboration of the topic, being the 'comment' component.[11] The canonical word order outside of the topic–comment structure is object–subject–verb (OSV), and noun phrases are head-initial.[15]

Relationships with other sign languages

Although the United Kingdom and the United States share English as the predominant oral language, British Sign Language is quite distinct from American Sign Language (ASL) - having only 31% signs identical, or 44% cognate.[16] BSL is also distinct from Irish Sign Language (ISL) (ISG in the ISO system) which is more closely related to French Sign Language (LSF) and ASL.

It is also distinct from Signed English, a manually coded method expressed to represent the English language.

The sign languages used in Australia and New Zealand, Auslan and New Zealand Sign Language, respectively, evolved largely from 19th century BSL, and all retain the same manual alphabet and grammar and possess similar lexicons. These three languages may technically be considered dialects of a single language (BANZSL) due to their use of the same grammar and manual alphabet and the high degree of lexical sharing (overlap of signs). The term BANZSL was coined by Trevor Johnston[17] and Adam Schembri.

In Australia deaf schools were established by educated deaf people from London, Edinburgh and Dublin. This introduced the London and Edinburgh dialects of BSL to Melbourne and Sydney respectively and Irish Sign Language to Sydney in Roman Catholic schools for the deaf. The language contact post secondary education between Australian ISL users and 'Australian BSL' users accounts for some of the dialectal differences we see between modern BSL and Auslan. Tertiary education in the US for some deaf Australian adults also accounts for some ASL borrowings found in modern Auslan.

Auslan, BSL and NZSL have 82% of signs identical (using concepts from a Swadesh list). When considering similar or related signs as well as identical, they are 98% cognate. Further information will be available after the completion of the BSL corpus is completed and allows for comparison with the Auslan corpus and the Sociolinguistic Variation in New Zealand Sign Language project . There continues to be language contact between BSL, Auslan and NZSL through migration (deaf people and interpreters), the media (television programmes such as See Hear, Switch, Rush and SignPost are often recorded and shared informally in all three countries) and conferences (the World Federation of the Deaf Conference – WFD – in Brisbane 1999 saw many British deaf people travelling to Australia).

Makaton, a communication system for people with cognitive impairments or other communication difficulties, was originally developed with signs borrowed from British Sign Language. The sign language used in Sri Lanka is also closely related to BSL despite the oral language not being English, demonstrating the distance between sign languages and spoken ones.

BSL users campaigned to have BSL recognised on an official level. BSL was recognised as a language in its own right by the UK government on 18 March 2003, but it has no legal protection. There is, however, legislation requiring the provision of interpreters such as the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984.

Usage

BSL has many regional dialects. Certain signs used in Scotland, for example, may not be understood immediately, or not understood at all, by those in Southern England, or vice versa. Some signs are even more local, occurring only in certain towns or cities (such as the Manchester system of number signs). Likewise, some may go in or out of fashion, or evolve over time, just as terms in oral languages do.[18] Families may have signs unique to them to accommodate for certain situations or to describe an object that may otherwise require fingerspelling.

Many British television channels broadcast programmes with in-vision signing, using BSL, as well as specially made programmes aimed mainly at deaf people such as the BBC's See Hear and Channel 4's VEE-TV.

BBC News broadcasts in-vision signing at 07:00-07:45, 08:00-08:20 and 13:00-13:45 GMT/BST each weekday. BBC Two also broadcasts in-vision signed repeats of the channel's primetime programmes between 00:00 and 02:00 each weekday. All BBC channels (excluding BBC One, BBC Alba and BBC Parliament) provide in-vision signing for some of their programmes.

BSL is used in some educational establishments, but is not always the policy for deaf children in some local authority areas. The Let's Sign BSL and fingerspelling graphics are being developed for use in education by deaf educators and tutors and include many of the regional signs referred to above.

In Northern Ireland, there are about 4,500 users of BSL and 1,500 users of Irish Sign Language, an unrelated sign language. A hybrid version, dubbed "Northern Ireland Sign Language" is also used.[19][20][21]

In 2019, over 100 signs for scientific terms, including 'deoxyribonucleotide' and 'deoxyribonucleoside', were added to BSL, after being conceived by Liam Mcmulkin, a deaf graduate of the University of Dundee, who had found finger-spelling such words tiresome, during his degree course.[22]

Number of BSL users

In 2016 the British Deaf Association says that, based on official statistics, it believes there are 151,000 people who use BSL in the UK, and 87,000 of these are deaf. This figure does not include professional BSL users, interpreters, translators, etc. unless they use BSL at home.[23]

Learning British Sign Language

British Sign Language can be learnt throughout the UK and three examination systems exist. Courses are provided by community colleges, local centres for deaf people and private organisations. Most tutors are native users of sign language and hold a relevant teaching qualification.

Becoming a BSL / English interpreter

There are two qualification routes: via post-graduate studies, or via National Vocational Qualifications. Deaf Studies undergraduate courses with specific streams for sign language interpreting exist at several British universities; post-graduate level interpreting diplomas are also on offer from universities and one private company. Course entry requirements vary from no previous knowledge of BSL to NVQ level 6 BSL (or equivalent).

The qualification process allows interpreters to register with the National Registers of Communication Professionals with Deaf and Deafblind People (NRCPD), a voluntary regulator. Registrants are asked to self-certify that they have both cleared a DBS (Disclosure and Barring Service) check and are covered by professional indemnity insurance. Completing a level 3 BSL language assessment and enrolling on an approved interpreting course allows applications to register as a TSLI (Trainee Sign Language Interpreter). After completing an approved interpreting course, trainees can then apply to achieve RSLI (Registered Sign Language Interpreter) status. RSLIs are currently required by NRCPD to log Continuous Professional Development activities. Post-qualification, specialist training is still considered necessary to work in specific critical domains.

Communication Support Workers

Communication Support Workers (CSWs) are professionals who support the communication of deaf students in education at all ages, and deaf people in many areas of work, using British Sign Language and other communication methods such as Sign Supported English. The qualifications and experience of CSWs varies: some are fully qualified interpreters, others are not.

Let Sign Shine

Let Sign Shine is a campaign started by Norfolk teenager Jade Chapman to raise the awareness of British Sign Language (BSL) and attract signatures for a petition for BSL to be taught in schools. The campaign's petition to the Parliament of the United Kingdom has attracted support from over four thousand people.

Chapman was nominated for the Bernard Matthews Youth Award 2014 for her work and devotion to raising awareness of the importance of sign language. Chapman won the education award category and was presented with an award by Olympic swimmer Rebecca Adlington.[24]

Chapman was also awarded an Outstanding Achievement Award from the Radio Norwich 99.9 Local Hero Awards on 7 October 2015. The award ceremony featured a performance by Alesha Dixon.[25]

Having been donated £1,000 from the Bernard Matthews Youth Award, Let Sign Shine used this to start a British Sign Language course at Dereham Neatherd High School.[26]

See also

- Languages in the United Kingdom

References

- British Sign Language (BSL) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- "BSL on paper" (PDF). Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- "British Sign Language Legislation". Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "British Sign Language". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- IPSOS Mori GP Patient Survey 2009/10

- 2011 Census: Quick Statistics for England and Wales, March 2011, Accessed 17 February 2013.

- Deaf people and linguistic research Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine, Professor Bencie Woll, Director of the Deafness, Cognition and Language Research Centre based at University College London. British Science Association. Accessed October 2010.

- Kyle & Woll (1985).Sign Language: the study of deaf people and their language Cambridge University Press, p. 263

- Sign Language: The Study of Deaf People and Their Language, J. G. Kyle, B. Woll, G. Pullen, F. Maddix, Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0521357179

- "Official recognition of British Sign Language 1987-2003 – suggested reading | UCL UCL Ear Institute & Action on Hearing Loss Libraries". Blogs.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Sutton-Spence, Rachel (1999). The Linguistics of British Sign Language. University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

- Morgan, Gary (October 2006). "'Children Are Just Lingual': The Development of Phonology in British Sign Language (BSL)". Lingua. 116.

- McArthur, Tom (January 2018). "British Sign Language". The Oxford Companion to the English Language.

- "Grammatical Structure of British Sign Language · coHearentVision". archive.is. 23 April 2013. Archived from the original on 23 April 2013.

- Sutton-Spence, R.; Woll, B. (1999). The Linguistics of British Sign Language: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521637183. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- McKee, D. & G. Kennedy (2000). Lexical Comparison of Signs from American, Australian, British, and New Zealand Sign Languages. In K. Emmorey and H. Lane (Eds), "The signs of language revisited: an anthology to honor Ursula Bellugi and Edward Klima". Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Johnston, T. (2002). BSL, Auslan and NZSL: Three sign languages or one? In A. Baker, B. van den Bogaerde & O. Crasborn (Eds.), "Cross-linguistic perspectives in sign language research: Selected papers from TISLR 2000" (pp. 47-69). Hamburg: Signum Verlag.

- Sutton-Spence, Rachel; Woll, Bencie (1998). The Linguistics of British Sign Language: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0521631424.

- "BSL Northern Ireland Sign Language at all public Masses. Archives".

- "Sign language is needed more than Irish: TUV's Allister" – via www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk.

- Gordon, Gareth (29 April 2020). "Bringing coronavirus news to the deaf community" – via www.bbc.com.

- Martin, Hazel (21 July 2019). "What's deoxyribonucleotide in sign language?". Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- "Help & Resources".

- East Anglian Daily Press, , Photo Gallery: Incredible young people from Norfolk and Suffolk are honoured with special awards.

- Let Sign Shine, Archived 8 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Norwich Radio Local Hero Award.

- BBC News, , Teenage campaigner Jade Chapman sets up sign language course with prize.