United States dollar

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, or American dollar) is the official currency of the United States and its territories per the Coinage Act of 1792. One dollar is divided into 100 cents (symbol: ¢), or into 1000 mills for accounting and taxing purposes (symbol: ₥). The Coinage Act of 1792 created a decimal currency by creating the dime, nickel, and penny coins, as well as the dollar, half dollar, and quarter dollar coins, all of which are still minted in 2020.

| United States dollar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| ISO 4217 | |||||

| Code | USD | ||||

| Number | 840 | ||||

| Exponent | 2 | ||||

| Denominations | |||||

| Superunit | |||||

| 4 | stella | ||||

| 10 | eagle | ||||

| 100 | union (slang) | ||||

| 1000 | grand, rack (slang) | ||||

| Subunit | |||||

| 1⁄4 | quarter | ||||

| 1⁄10 | dime | ||||

| 1⁄20 | nickel or half dime | ||||

| 1⁄100 | cent or penny | ||||

| 1⁄1000 | mill | ||||

| Symbol | $, U$, US$ | ||||

| cent or penny | ¢ | ||||

| mill | ₥ | ||||

| Nickname | List of nicknames

| ||||

| Banknotes | |||||

| Freq. used | $1, $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 | ||||

| Rarely used | $2 (still printed); $500, $1,000, $5,000, $10,000 (discontinued, still legal tender) | ||||

| Coins | |||||

| Freq. used | 1¢, 5¢, 10¢, 25¢ | ||||

| Rarely used | 50¢, $1 (still minted); ½¢, 2¢, 3¢, 3¢, 20¢, $2.50, $3, $20 (discontinued, still legal tender); $5, $10 (legal tender, now commemorative only) | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Date of introduction | April 2, 1792 | ||||

| Source | [1] | ||||

| Replaced | Continental currency Various foreign currencies, including: Pound sterling Spanish dollar | ||||

| User(s) | |||||

| Issuance | |||||

| Central bank | Federal Reserve System | ||||

| Website | www | ||||

| Printer | Bureau of Engraving and Printing | ||||

| Website | www | ||||

| Mint | United States Mint | ||||

| Website | www | ||||

| Valuation | |||||

| Inflation | 2.29% (December 2019) | ||||

| Source | inflationdata.com | ||||

| Method | CPI | ||||

| Pegged by | 30 currencies

| ||||

Several forms of paper money were introduced by Congress over the years, the latest of which being the Federal Reserve Note that was authorized by the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. While all existing U.S. currency remains legal tender,[6] issuance of the previous form of the currency (U.S. notes) was discontinued in January 1971.[7] As a result, paper money that is in current circulation consists primarily of Federal Reserve Notes that are denominated in U.S. dollars.[8]

Since the convertibility of paper U.S. currency into any precious metal was suspended in 1971,[9] the U.S. dollar is de facto fiat money.[10] Not only is the U.S. dollar the world's primary reserve currency as the most used in international transactions,[11] it is the official currency in several countries and the de facto currency in many others.[12][13] Aside from the United States itself, the American dollar is also used as the sole currency in two British Overseas Territories in the Caribbean: the British Virgin Islands and Turks and Caicos Islands. A few countries use the Federal Reserve Notes for paper money while still minting their own coins, or also accepting U.S. dollar coins (such as the Sacagawea or Presidential dollar). As of January 31, 2019, there is approximately US$1.7 trillion in circulation, $1.65 trillion of which is in the Federal Reserve Notes (the remaining $50 billion is in the form of U.S. notes and coins).[14]

The U.S. dollar as a currency is sometimes referred to as the greenback by foreign exchange traders and the financial press in other countries, such as Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India.[15][16][17][18][19]

Overview

Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution provides that Congress has the power "[t]o coin money."[20] Laws implementing this power are currently codified in Title 31 of the U.S. Code, under Section 5112, which prescribes the forms in which the United States dollars should be issued.[21] These coins are both designated in the section as "legal tender" in payment of debts.[21] The Sacagawea dollar is one example of the copper alloy dollar, in contrast to the American Silver Eagle which is pure silver. Section 5112 also provides for the minting and issuance of other coins, which have values ranging from one cent (U.S. Penny) to 100 dollars.[21] These other coins are more fully described in Coins of the United States dollar.

Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution provides that "a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time,"[22] which is further specified by Section 331 of Title 31 of the U.S. Code.[23] The sums of money reported in the "Statements" are currently expressed in U.S. dollars, thus the U.S. dollar may be described as the unit of account of the United States.[24] "Dollar" is one of the first words of Section 9, in which the term refers to the Spanish milled dollar, a coin that had a monetary value of 8 Spanish units of currency, or reales.

The Coinage Act

In 1792, the U.S. Congress passed the Coinage Act, of which Section 9 authorized the production of various coins, including:[25]:248

DOLLARS or UNITS—each to be of the value of a Spanish milled dollar as the same is now current, and to contain three hundred and seventy-one grains and four sixteenth parts of a grain of pure, or four hundred and sixteen grains of standard silver.

Section 20 of the Act designates the United States dollar as the unit of currency of the United States:[25]:250–1

[T]he money of account of the United States shall be expressed in dollars, or units…and that all accounts in the public offices and all proceedings in the courts of the United States shall be kept and had in conformity to this regulation.

Denominations

Unlike the Spanish milled dollar, the U.S. dollar has been based upon a decimal system of values since the time of the Continental Congress.[26] This decimal system was again described in the Coinage Act of 1792, which, in addition to the dollar, officially established the following monetary units, with prescribed weights and composition of gold, silver, or copper for each:[27]

- mill (₥), or one-thousandth of a dollar;

- cent (¢), or one-hundredth of a dollar;

- dime, or one-tenth of a dollar; and

- eagle, or ten dollars.

Only cents are in everyday divisions of the dollar: dime is used solely as the name of the coin with the value of 10¢, while eagle is largely unknown to the general public.[28] Though mill is also relatively unknown, it is sometimes used in matters of tax levies, and gasoline prices, which are usually in the form of $ΧΧ.ΧΧ9 per gallon (e.g., $3.599, commonly written as $3.59 9⁄10).[29][28]

When currently issued in circulating form, denominations less than or equal to a dollar are emitted as U.S. coins, while denominations greater than or equal to a dollar are emitted as Federal Reserve Notes (with the exception of gold, silver, platinum, and palladium coins valued up to $100 as legal tender, though worth far more as bullion). Both one-dollar coins and notes are produced today, although the note form is significantly more common.

In the past, "paper money" was occasionally issued in denominations less than a dollar (fractional currency) and gold coins were issued for circulation up to the value of $20 (known as the double eagle, discontinued in the 1930s). The term eagle was used in the Coinage Act of 1792 for the denomination of ten dollars, and subsequently was used in naming gold coins. Paper currency less than one dollar in denomination, i.e. fractional currency, was also sometimes pejoratively referred to as shinplasters.

In 1854, Secretary of the Treasury James Guthrie proposed creating $100, $50, and $25 gold coins, to be referred to as a union, half union, and quarter union, respectively,[30] thus implying a denomination of 1 Union = $100. However, no such coins were ever struck, and only patterns for the $50 half union exist.

Physical attributes

Today, USD notes are made from cotton fiber paper, as opposed to wood fiber, which is most often used to make common paper. U.S. coins are produced by the U.S. Mint. USD banknotes are printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and, since 1914, have been issued by the Federal Reserve. The "large-sized notes" issued before 1928 measured 7.42 in × 3.125 in (188.5 mm × 79.4 mm), while small-sized notes introduced that year measure 6.14 in × 2.61 in × 0.0043 in (155.96 mm × 66.29 mm × 0.11 mm).

When the current, smaller sized U.S. currency was introduced it was referred to as Philippine-sized currency, as the Philippines had previously adopted the same size for its legal currency, the Philippine peso.

Etymology

In the 16th century, Count Hieronymus Schlick of Bohemia began minting coins known as joachimstalers, named for Joachimstal, the valley in which the silver was mined. In turn, the valley's name is titled after Saint Joachim, whereby thal or tal, a cognate of the English word dale, is German for 'valley.'[31] The joachimstaler was later shortened to the German taler, a word that eventually found its way into many languages, including:[31]

- Danish and Swedish as daler;

- Norwegian as dalar and daler;

- Dutch as daler or daalder;

- Ethiopian as talari;

- Hungarian as tallér;

- Italian as tallero; and

- English as dollar.

Alternatively, thaler is said to come from the German coin guldengroschen ('great guilder', being of silver but equal in value to a gold guilder), minted from the silver of Joachimsthal. The coins minted in the valley soon lent their name to other coins of similar size and weight from other places. The Dutch coin depicting a lion, for instance, was thus named leeuwendaler ('lion dollar'). The leeuwendaler was authorized to contain 427.16 grains of .75 fine silver and passed locally for between 36 and 42 stuivers. Being lighter than the large-denomination coins then in circulation, it was more advantageous for Dutch merchants to pay foreign debt in leeuwendalers, therefore making such the coin of choice for foreign trade.

The leeuwendaler was popular in the Dutch East Indies and in the Dutch North American New Netherland Colony (today the New York metropolitan area), and circulated throughout the Thirteen Colonies during the 17th and early 18th centuries. It was also separately popular throughout Eastern Europe, where it led to the current Romanian and Moldovan currency, leu ('lion').

Among the English-speaking community, the Dutch coin came to be popularly known as lion dollar—what would become the origin of the English dollar.[32] The modern American-English pronunciation of dollar is still remarkably close to the 17th-century Dutch pronunciation of daler.[33] By analogy with this lion dollar, Spanish pesos—with the same weight and shape as the lion dollar—came to be known as Spanish dollars.[33] By the mid-18th century, the lion dollar had been replaced by the Spanish dollar, famously known as the 'piece of eight,' which was distributed widely in the Spanish colonies of the New World and in the Philippines.[34] Eventually, dollar became the name of the official American currency.

Nicknames

Dollars in general

The colloquialism buck(s) (much like the British quid for the pound sterling) is often used to refer to dollars of various nations, including the U.S. dollar. This term, dating to the 18th century, may have originated with the colonial leather trade, or it may also have originated from a poker term.[35] Likewise, the $1 note has been nicknamed buck, as well as single.

Greenback is another nickname, originally applied specifically to the 19th-century Demand Note dollars, which were printed black and green on the back side, created by Abraham Lincoln to finance the North for the Civil War.[36] It is still used to refer to the U.S. dollar (but not to the dollars of other countries). The term greenback is also used by foreign exchange traders in reference to the U.S. dollar as a currency,[15] and by the financial press in other countries, such as Australia,[16] New Zealand,[17] South Africa,[18] and India.[19]

Other well-known names of the dollar as a whole in denominations include greenmail, green, and dead presidents, the latter of which referring to the deceased presidents pictured on most bills. Dollars in general have also been known as bones (e.g. "twenty bones" = $20). The newer designs, with portraits displayed in the main body of the obverse (rather than in cameo insets), upon paper color-coded by denomination, are sometimes referred to as bigface notes or Monopoly money.

Piastre was the original French word for the U.S. dollar, used for example in the French text of the Louisiana Purchase. Calling the dollar a piastre is still common among the speakers of Cajun French and New England French. Modern French uses dollar for this unit of currency as well. The term is still used as slang for U.S. dollars in the French-speaking Caribbean islands, most notably Haiti.

Specific to denomination

The infrequently-used $2 note is sometimes called deuce, Tom, or Jefferson (after Thomas Jefferson). Contrastly, the $5 bill has been called Lincoln, fin, fiver, and five-spot. The $50 bill is occasionally called a yardstick, or a grant, after President Ulysses S. Grant, pictured on the obverse. The $20 note has been referred to as a double sawbuck, Jackson (after Andrew Jackson), and double eagle. The $10 note can be referred to as a sawbuck, ten-spot, or Hamilton (after Alexander Hamilton).

Benjamin, Benji, Ben, or Franklin, refers to the $100 bill, which features the likeness of the eponymous Benjamin Franklin. Other nicknames include C-note (C being the Roman numeral for 100), century note, and bill (e.g. two bills = $200).

A grand (sometimes shortened to simply G) is a common term for the amount of $1,000, though the thousand-dollar note is no longer in general use. The suffix K or k (from kilo) is also commonly used to denote this amount (e.g. $10k = $10,000). Likewise, a large or stack usually references to a multiple of 1,000 (e.g. "fifty large" = $50,000).

Dollar sign

The symbol $, usually written before the numerical amount, is used for the U.S. dollar (as well as for many other currencies). The sign was the result of a late 18th-century evolution of the scribal abbreviation ps for the peso, the common name for the Spanish dollars that were in wide circulation in the New World from the 16th to the 19th centuries. These Spanish pesos or dollars were minted in Spanish America, namely in Mexico City; Potosí, Bolivia; and Lima, Peru. The p and the s eventually came to be written over each other giving rise to $.[37][38][39][40]

Another popular explanation is that it is derived from the Pillars of Hercules on the Spanish Coat of arms of the Spanish dollar. These Pillars of Hercules on the silver Spanish dollar coins take the form of two vertical bars (||) and a swinging cloth band in the shape of an S.

Yet another explanation suggests that the dollar sign was formed from the capital letters U and S written or printed one on top of the other. This theory, popularized by novelist Ayn Rand in Atlas Shrugged,[41] does not consider the fact that the symbol was already in use before the formation of the United States.[42]

History

The American dollar coin was initially based on the value and look of the Spanish dollar or piece of eight, used widely in Spanish America from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The first dollar coins issued by the United States Mint (founded 1792) were similar in size and composition to the Spanish dollar, minted in Mexico and Peru. The Spanish, U.S. silver dollars, and later, Mexican silver pesos circulated side by side in the United States, and the Spanish dollar and Mexican peso remained legal tender until the Coinage Act of 1857. The coinage of various English colonies also circulated. The lion dollar was popular in the Dutch New Netherland Colony (New York), but the lion dollar also circulated throughout the English colonies during the 17th century and early 18th century. Examples circulating in the colonies were usually worn so that the design was not fully distinguishable, thus they were sometimes referred to as "dog dollars".[43]

On the 6th of July 1785, the Continental Congress resolved that the money unit of the United States, the dollar, would contain 375.64 grains of fine silver; on the 8th of August 1786, the Continental Congress continued that definition and further resolved that the money of account, corresponding with the division of coins, would proceed in a decimal ratio, with the sub-units being mills at 0.001 of a dollar, cents at 0.010 of a dollar, and dimes at 0.100 of a dollar.[26]

After the adoption of the United States Constitution, the U.S. dollar was defined by the Coinage Act of 1792, which specified a "dollar" to be based in the Spanish milled dollar and of 371 grains and 4 sixteenths part of a grain of pure or 416 grains (27.0 g) of standard silver and an "eagle" to be 247 and 4 eighths of a grain or 270 grains (17 g) of gold (again depending on purity).[44] The choice of the value 371 grains arose from Alexander Hamilton's decision to base the new American unit on the average weight of a selection of worn Spanish dollars. Hamilton got the treasury to weigh a sample of Spanish dollars and the average weight came out to be 371 grains. A new Spanish dollar was usually about 377 grains in weight, and so the new U.S. dollar was at a slight discount in relation to the Spanish dollar.

The same coinage act also set the value of an eagle at 10 dollars, and the dollar at 1⁄10 eagle. It called for 90% silver alloy coins in denominations of 1, 1⁄2, 1⁄4, 1⁄10, and 1⁄20 dollars; it called for 90% gold alloy coins in denominations of 1, 1⁄2, 1⁄4, and 1⁄10 eagles. The value of gold or silver contained in the dollar was then converted into relative value in the economy for the buying and selling of goods. This allowed the value of things to remain fairly constant over time, except for the influx and outflux of gold and silver in the nation's economy.[45]

The early currency of the United States did not exhibit faces of presidents, as is the custom now;[46] although today, by law, only the portrait of a deceased individual may appear on United States currency.[47] In fact, the newly formed government was against having portraits of leaders on the currency, a practice compared to the policies of European monarchs.[48] The currency as we know it today did not get the faces they currently have until after the early 20th century; before that "heads" side of coinage used profile faces and striding, seated, and standing figures from Greek and Roman mythology and composite Native Americans. The last coins to be converted to profiles of historic Americans were the dime (1946) and the Dollar (1971).

For articles on the currencies of the colonies and states, see Connecticut pound, Delaware pound, Georgia pound, Maryland pound, Massachusetts pound, New Hampshire pound, New Jersey pound, New York pound, North Carolina pound, Pennsylvania pound, Rhode Island pound, South Carolina pound, and Virginia pound.

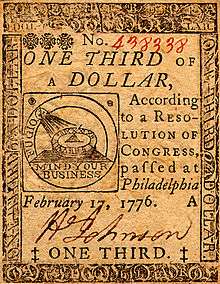

Continental currency

During the American Revolution the thirteen colonies became independent states. Freed from British monetary regulations, they each issued £sd paper money to pay for military expenses. The Continental Congress also began issuing "Continental Currency" denominated in Spanish dollars. The dollar was valued relative to the states' currencies at the following rates:

- 5 shillings – Georgia

- 6 shillings – Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Virginia

- 7 1⁄2 shillings – Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania

- 8 shillings – New York, North Carolina

- 32 1⁄2 shillings – South Carolina

Continental currency depreciated badly during the war, giving rise to the famous phrase "not worth a continental".[49] A primary problem was that monetary policy was not coordinated between Congress and the states, which continued to issue bills of credit. Additionally, neither Congress nor the governments of the several states had the will or the means to retire the bills from circulation through taxation or the sale of bonds.[50] The currency was ultimately replaced by the silver dollar at the rate of 1 silver dollar to 1000 continental dollars.

Silver and gold standards

From 1792, when the Mint Act was passed, the dollar was defined as 371.25 grains (24.056 g) of silver. The gold coins that were minted were not given any denomination and traded for a market value relative to the Congressional standard of the silver dollar. 1834 saw a shift in the gold standard to 23.2 grains (1.50 g), followed by a slight adjustment to 23.22 grains (1.505 g) in 1837 (16:1 ratio).

In 1862, paper money was issued without the backing of precious metals, due to the Civil War. Silver and gold coins continued to be issued and in 1878 the link between paper money and coins was reinstated. This disconnection from gold and silver backing also occurred during the War of 1812. The use of paper money not backed by precious metals had also occurred under the Articles of Confederation from 1777 to 1788. With no solid backing and being easily counterfeited, the continentals quickly lost their value, giving rise to the phrase "not worth a continental". This was a primary reason for the "No state shall... make any thing but gold and silver coin a tender in payment of debts" clause in article 1, section 10 of the United States Constitution.

In order to finance the War of 1812, Congress authorized the issuance of Treasury Notes, interest-bearing short-term debt that could be used to pay public dues. While they were intended to serve as debt, they did function "to a limited extent" as money. Treasury Notes were again printed to help resolve the reduction in public revenues resulting from the Panic of 1837 and the Panic of 1857, as well as to help finance the Mexican–American War and the Civil War.

In addition to Treasury Notes, in 1861, Congress authorized the Treasury to borrow $50 million in the form of Demand Notes, which did not bear interest but could be redeemed on demand for precious metals. However, by December 1861, the Union government's supply of specie was outstripped by demand for redemption and they were forced to suspend redemption temporarily. The following February, Congress passed the Legal Tender Act of 1862, issuing United States Notes, which were not redeemable on demand and bore no interest, but were legal tender, meaning that creditors had to accept them at face value for any payment except for public debts and import tariffs. However, silver and gold coins continued to be issued, resulting in the depreciation of the newly printed notes through Gresham's Law. In 1869, Supreme Court ruled in Hepburn v. Griswold that Congress could not require creditors to accept United States Notes, but overturned that ruling the next year in the Legal Tender Cases. In 1875, Congress passed the Specie Payment Resumption Act, requiring the Treasury to allow US Notes to be redeemed for gold after January 1, 1879. The Treasury ceased to issue United States Notes in 1971.

The Gold Standard Act of 1900 abandoned the bimetallic standard and defined the dollar as 23.22 grains (1.505 g) of gold, equivalent to setting the price of 1 troy ounce of gold at $20.67. Silver coins continued to be issued for circulation until 1964, when all silver was removed from dimes and quarters, and the half dollar was reduced to 40% silver. Silver half dollars were last issued for circulation in 1970. Gold coins were confiscated by Executive Order 6102 issued in 1933 by Franklin Roosevelt. The gold standard was changed to 13.71 grains (0.888 g), equivalent to setting the price of 1 troy ounce of gold at $35. This standard persisted until 1968.

Between 1968 and 1975, a variety of pegs to gold were put in place, eventually culminating in a sudden end, on August 15, 1971, to the convertibility of dollars to gold later dubbed the Nixon Shock. The last peg was $42.22 per ounce before the U.S. dollar was allowed to freely float on currency markets.

According to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the largest note it ever printed was the $100,000 Gold Certificate, Series 1934. These notes were printed from December 18, 1934, through January 9, 1935, and were issued by the Treasurer of the United States to Federal Reserve Banks only against an equal amount of gold bullion held by the Treasury. These notes were used for transactions between Federal Reserve Banks and were not circulated among the general public.

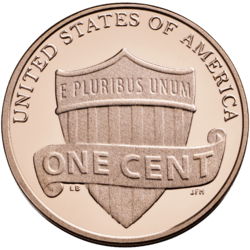

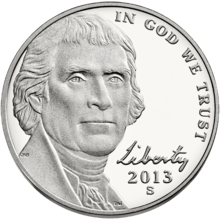

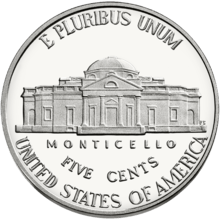

Coins

Official United States coins have been produced every year from 1792 to the present. From 1934 to present, the only denominations produced for circulation have been the familiar penny, nickel, dime, quarter, half dollar and dollar. The nickel is the only coin still in use today that is essentially unchanged (except in its design) from its original version. Every year since 1866, the nickel has been 75% copper and 25% nickel, except for 4 years during World War II when nickel was needed for the war.

Due to the penny's low value, some efforts have been made to eliminate the penny as circulating coinage.[51][52]

| Denomination | Common name | Front | Reverse | Portrait and design date | Reverse motif and design date | Weight | Diameter | Material | Edge | Circulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cent 1¢ |

penny |  |

|

Abraham Lincoln | Union Shield | 2.5 g (0.088 oz) |

0.75 in (19.05 mm) |

97.5% Zn covered by 2.5% Cu | Plain | Wide |

| Five cents 5¢ |

nickel |  |

|

Thomas Jefferson | Monticello | 5.0 g (0.176 oz) |

0.835 in (21.21 mm) |

75% Cu 25% Ni |

Plain | Wide |

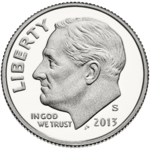

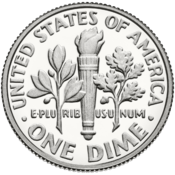

| Dime 10¢ |

dime |  |

|

Franklin D. Roosevelt | olive branch, torch, oak branch | 2.268 g (0.08 oz) |

0.705 in (17.91 mm) |

91.67% Cu 8.33% Ni |

118 reeds | Wide |

| Quarter dollar 25¢ |

quarter |  |

|

George Washington | Various; five designs per year | 5.67 g (0.2 oz) |

0.955 in (24.26 mm) |

91.67% Cu 8.33% Ni |

119 reeds | Wide |

| Half dollar 50¢ |

half |  |

|

John F. Kennedy | Presidential Seal | 11.34 g (0.4 oz) |

1.205 in (30.61 mm) |

91.67% Cu 8.33% Ni |

150 reeds | Limited |

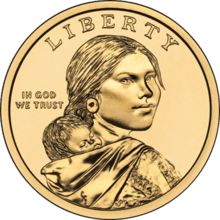

| Dollar coin $1 |

dollar coin, golden dollar |  |

|

Profile of Sacagawea with her child, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau | Bald eagle in flight (2000–2008), Various; new design per year | 8.10 g (0.286 oz) |

1.043 in (26.50 mm) |

88.5% Cu 6% Zn 3.5% Mn 2% Ni |

Lettered | Limited |

Discontinued and cancelled denominations

Discontinued and canceled coin denominations include:

- Half cent: 1⁄2¢, 1793–1857

- Silver center cent: 1¢, 1792 (not circulated)

- Ring cent: 1¢, 1850–1851, 1853, 1884–1885 (not circulated)

- Two-cent billon: 2¢, 1836 (not circulated)

- Two-cent bronze: 2¢, 1863–1873

- Two and a half cent piece: 2.5¢ (planned but not minted)

- Three-cent bronze: 3¢, 1863 (not circulated)

- Three-cent nickel: 3¢, 1865–1889

- Trime (Three-cent silver): 3¢, 1851–1873

- Half dime: 5¢, 1792–1873

- Twenty-cent piece: 20¢, 1875–1878

- Gold dollar: $1.00, 1849–1889

- Two dollar piece: $2.00 (planned but not minted)

- Quarter eagle: $2.50, 1792–1929

- Three-dollar piece: $3.00, 1854–1889

- Stella: $4.00, 1879–1880 (not circulated)

- Half eagle: $5.00, 1795–1929 (some modern commemoratives are minted in this denomination)

- Eagle: $10.00, 1795–1933 (some modern commemoratives are minted in this denomination)

- Double eagle: $20.00, 1849–1933, 2009

- Half-union: $50.00, 1877 (not circulated)

- Union (coin): $100.00 (planned but not minted)

Collector coins

Collector coins for which everyday transactions are non-existent.[53]

- American Eagles originally were not available from the Mint for individuals but had to be purchased from authorized dealers. In 2006, the Mint began direct sales to individuals of uncirculated bullion coins with a special finish, and bearing a "W" mintmark.

- American Silver Eagle $1 (1 troy oz) Silver bullion coin 1986–present

- American Gold Eagle $5 (1⁄10 troy oz), $10 (1⁄4 troy oz), $25 (1⁄2 troy oz), and $50 (1 troy oz) Gold bullion coin 1986–present

- American Platinum Eagle $10 (1⁄10 troy oz), $25 (1⁄4 troy oz), $50 (1⁄2 troy oz), and $100 (1 troy oz) Platinum bullion coin 1997–present

- American Palladium Eagle $25 (1 troy oz) Palladium bullion coin 2017–present

- United States commemorative coins—special issue coins

- $50.00 (Half Union) 1915

- Presidential Proofs (see below) 2007–present

Technically, all these coins are still legal tender at face value, though some are far more valuable today for their numismatic value, and for gold and silver coins, their precious metal value. From 1965 to 1970 the Kennedy half dollar was the only circulating coin with any silver content, which was removed in 1971 and replaced with cupronickel. However, since 1992, the U.S. Mint has produced special Silver Proof Sets in addition to the regular yearly proof sets with silver dimes, quarters, and half dollars in place of the standard copper-nickel versions. In addition, an experimental $4.00 (Stella) coin was also minted in 1879, but never placed into circulation, and is properly considered to be a pattern rather than an actual coin denomination.

The $50 coin mentioned was only produced in 1915 for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (1915) celebrating the opening of the Panama Canal. Only 1,128 were made, 645 of which were octagonal; this remains the only U.S. coin that was not round as well as the largest and heaviest U.S. coin ever produced. A $100 gold coin was produced in High relief during 2015, although it was primarily produced for collectors, not for general circulation.[54]

Proof Sets

The United States Mint produces Proof Sets specifically for collectors and speculators. Silver Proofs tend to be the standard designs but with the dime, quarter, and half dollar containing 90% silver. Starting in 1983 and ending in 1997, the Mint also produced proof sets containing the year's commemorative coins alongside the regular coins. Another type of proof set is the Presidential Dollar Proof Set where the four special $1 coins are minted each year featuring a president. Because of budget constraints and increasing stockpiles of these relatively unpopular coins, the production of new Presidential dollar coins for circulation was suspended on December 13, 2011, by U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner. Presidential dollars (along with all other dollar coin series) minted from 2012 onward were made solely for collectors.[55]

- 2007 had George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison

- 2008 had James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, and Martin Van Buren

- 2009 had William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor

- 2010 had Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan, and Abraham Lincoln

- 2011 had Andrew Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, and James A. Garfield

- 2012 had Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland (1st term), Benjamin Harrison, and Grover Cleveland (2nd term)

- 2013 had William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson

- 2014 had Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, and Franklin D. Roosevelt

- 2015 had Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson

- 2016 had Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, James E. Carter and Ronald Reagan.

Dollar coins

The first United States dollar was minted in 1794. Known as the Flowing Hair Dollar, it contained 416 grains of "standard silver" (89.25% silver and 10.75% copper), as specified by Section 13[56] of the Coinage Act of 1792. It was designated by Section 9 of that Act as having "the value of a Spanish milled dollar."

Dollar coins have not been very popular in the United States.[57] Silver dollars were minted intermittently from 1794 through 1935; a copper-nickel dollar of the same large size, featuring President Dwight D. Eisenhower, was minted from 1971 through 1978. Gold dollars were also minted in the 19th century. The Susan B. Anthony dollar coin was introduced in 1979; these proved to be unpopular because they were often mistaken for quarters, due to their nearly equal size, their milled edge, and their similar color. Minting of these dollars for circulation was suspended in 1980 (collectors' pieces were struck in 1981), but, as with all past U.S. coins, they remain legal tender. As the number of Anthony dollars held by the Federal Reserve and dispensed primarily to make change in postal and transit vending machines had been virtually exhausted, additional Anthony dollars were struck in 1999. In 2000, a new dollar coin featuring Sacagawea was introduced, which corrected some of the problems of the Anthony dollar by having a smooth edge and a gold color, without requiring changes to vending machines that accept the Anthony dollar. However, this new coin has failed to achieve the popularity of the still-existing dollar bill and is rarely used in daily transactions. The failure to simultaneously withdraw the dollar bill and weak publicity efforts have been cited by coin proponents as primary reasons for the failure of the dollar coin to gain popular support.[58]

In February 2007, the U.S. Mint, under the Presidential $1 Coin Act of 2005,[59] introduced a new $1 U.S. Presidential dollar coin. Based on the success of the "50 State Quarters" series, the new coin features a sequence of presidents in order of their inaugurations, starting with George Washington, on the obverse side. The reverse side features the Statue of Liberty. To allow for larger, more detailed portraits, the traditional inscriptions of "E Pluribus Unum", "In God We Trust", the year of minting or issuance, and the mint mark will be inscribed on the edge of the coin instead of the face. This feature, similar to the edge inscriptions seen on the British £1 coin, is not usually associated with U.S. coin designs. The inscription "Liberty" has been eliminated, with the Statue of Liberty serving as a sufficient replacement. In addition, due to the nature of U.S. coins, this will be the first time there will be circulating U.S. coins of different denominations with the same president featured on the obverse (heads) side (Lincoln/penny, Jefferson/nickel, Franklin D. Roosevelt/dime, Washington/quarter, Kennedy/half dollar, and Eisenhower/dollar). Another unusual fact about the new $1 coin is Grover Cleveland will have two coins with two different portraits issued due to the fact he was the only U.S. president to be elected to two non-consecutive terms.[60]

Early releases of the Washington coin included error coins shipped primarily from the Philadelphia mint to Florida and Tennessee banks. Highly sought after by collectors, and trading for as much as $850 each within a week of discovery, the error coins were identified by the absence of the edge impressions "E PLURIBUS UNUM IN GOD WE TRUST 2007 P". The mint of origin is generally accepted to be mostly Philadelphia, although identifying the source mint is impossible without opening a mint pack also containing marked units. Edge lettering is minted in both orientations with respect to "heads", some amateur collectors were initially duped into buying "upside down lettering error" coins.[61] Some cynics also erroneously point out that the Federal Reserve makes more profit from dollar bills than dollar coins because they wear out in a few years, whereas coins are more permanent. The fallacy of this argument arises because new notes printed to replace worn out notes, which have been withdrawn from circulation, bring in no net revenue to the government to offset the costs of printing new notes and destroying the old ones. As most vending machines are incapable of making change in banknotes, they commonly accept only $1 bills, though a few will give change in dollar coins.

Mint marks

| Mint | Mint mark | Metal minted | Year established | Current status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denver | D | All metals | 1906 | Facility open |

| Philadelphia | P or none[lower-alpha 4] | All metals | 1792 | Facility open |

| San Francisco | S | All metals | 1854 | Facility open (mainly produces proof) |

| West Point | W or none[lower-alpha 5] | Gold, Silver, Platinum and Palladium | 1973 | Facility open (mainly produces bullion) |

| Carson City | CC | Gold and Silver | 1870 | Facility closed, 1893[lower-alpha 6] |

| Charlotte | C | Gold only | 1838 | Facility closed, 1861 |

| Dahlonega | D[lower-alpha 7] | Gold only | 1838 | Facility closed, 1861 |

| Manila[lower-alpha 8] | M or none[lower-alpha 9] | All metals | 1920 | Facility closed, 1922; re-opened 1925–1941 |

| New Orleans | O | Gold and Silver | 1838 | Facility closed, 1861; re-opened 1879–1909[lower-alpha 10] |

Banknotes

| Denomination | Front | Reverse | Portrait | Reverse motif | First series | Latest series | Circulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One Dollar |  |

|

George Washington | Great Seal of the United States | Series 1963[lower-alpha 11] Series 1935[lower-alpha 12] |

Series 2017A[62] | Wide |

| Two Dollars |  |

|

Thomas Jefferson | Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull | Series 1976 | Series 2017A | Limited |

| Five Dollars |  |

|

Abraham Lincoln | Lincoln Memorial | Series 2006 | Series 2017A | Wide |

| Ten Dollars |  |

|

Alexander Hamilton | U.S. Treasury | Series 2004A | Series 2017A | Wide |

| Twenty Dollars |  |

|

Andrew Jackson | White House | Series 2004 | Series 2017A | Wide |

| Fifty Dollars |  |

|

Ulysses S. Grant | United States Capitol | Series 2004 | Series 2013 | Wide |

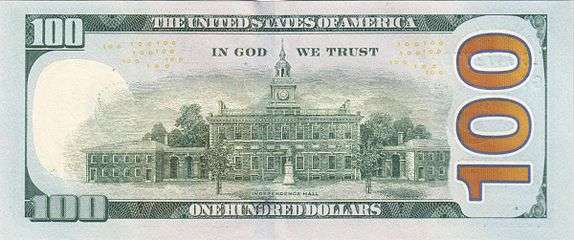

| One Hundred Dollars |  |

|

Benjamin Franklin | Independence Hall | Series 2009 | Series 2017A | Wide |

The U.S. Constitution provides that Congress shall have the power to "borrow money on the credit of the United States."[63] Congress has exercised that power by authorizing Federal Reserve Banks to issue Federal Reserve Notes. Those notes are "obligations of the United States" and "shall be redeemed in lawful money on demand at the Treasury Department of the United States, in the city of Washington, District of Columbia, or at any Federal Reserve bank".[64] Federal Reserve Notes are designated by law as "legal tender" for the payment of debts.[65] Congress has also authorized the issuance of more than 10 other types of banknotes, including the United States Note[66] and the Federal Reserve Bank Note. The Federal Reserve Note is the only type that remains in circulation since the 1970s.

Currently printed denominations are $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100. Notes above the $100 denomination stopped being printed in 1946 and were officially withdrawn from circulation in 1969. These notes were used primarily in inter-bank transactions or by organized crime; it was the latter usage that prompted President Richard Nixon to issue an executive order in 1969 halting their use. With the advent of electronic banking, they became less necessary. Notes in denominations of $500, $1,000, $5,000, $10,000, and $100,000 were all produced at one time; see large denomination bills in U.S. currency for details. With the exception of the $100,000 bill (which was only issued as a Series 1934 Gold Certificate and was never publicly circulated; thus it is illegal to own), these notes are now collectors' items and are worth more than their face value to collectors.

Though still predominantly green, post-2004 series incorporate other colors to better distinguish different denominations. As a result of a 2008 decision in an accessibility lawsuit filed by the American Council of the Blind, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing is planning to implement a raised tactile feature in the next redesign of each note, except the $1 and the current version of the $100 bill. It also plans larger, higher-contrast numerals, more color differences, and distribution of currency readers to assist the visually impaired during the transition period.[67]

Means of issue

The monetary base consists of coins and Federal Reserve Notes in circulation outside the Federal Reserve Banks and the U.S. Treasury, plus deposits held by depository institutions at Federal Reserve Banks. The adjusted monetary base has increased from approximately 400 billion dollars in 1994, to 800 billion in 2005, over 3000 billion in 2013.[68] The amount of cash in circulation is increased (or decreased) by the actions of the Federal Reserve System. Eight times a year, the 12-person Federal Open Market Committee meets to determine U.S. monetary policy.[69] Every business day, the Federal Reserve System engages in Open market operations to carry out that monetary policy.[70] If the Federal Reserve desires to increase the money supply, it will buy securities (such as U.S. Treasury Bonds) anonymously from banks in exchange for dollars. Conversely, it will sell securities to the banks in exchange for dollars, to take dollars out of circulation.[71]

When the Federal Reserve makes a purchase, it credits the seller's reserve account (with the Federal Reserve). This money is not transferred from any existing funds—it is at this point that the Federal Reserve has created new high-powered money. Commercial banks can freely withdraw in cash any excess reserves from their reserve account at the Federal Reserve. To fulfill those requests, the Federal Reserve places an order for printed money from the U.S. Treasury Department.[72] The Treasury Department in turn sends these requests to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (to print new dollar bills) and the Bureau of the Mint (to stamp the coins).

Usually, the short-term goal of open market operations is to achieve a specific short-term interest rate target. In other instances, monetary policy might instead entail the targeting of a specific exchange rate relative to some foreign currency or else relative to gold. For example, in the case of the United States the Federal Reserve targets the federal funds rate, the rate at which member banks lend to one another overnight. The other primary means of conducting monetary policy include: (i) Discount window lending (as lender of last resort); (ii) Fractional deposit lending (changes in the reserve requirement); (iii) Moral suasion (cajoling certain market players to achieve specified outcomes); (iv) "Open mouth operations" (talking monetary policy with the market).

Value

|

|

|

The 6th paragraph of Section 8 of Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution provides that the U.S. Congress shall have the power to "coin money" and to "regulate the value" of domestic and foreign coins. Congress exercised those powers when it enacted the Coinage Act of 1792. That Act provided for the minting of the first U.S. dollar and it declared that the U.S. dollar shall have "the value of a Spanish milled dollar as the same is now current".[73]

The table to the right shows the equivalent amount of goods that, in a particular year, could be purchased with $1. The table shows that from 1774 through 2012 the U.S. dollar has lost about 97.0% of its buying power.[74]

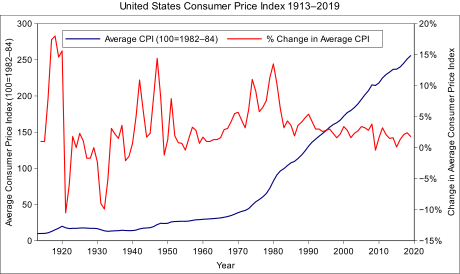

The decline in the value of the U.S. dollar corresponds to price inflation, which is a rise in the general level of prices of goods and services in an economy over a period of time.[75] A consumer price index (CPI) is a measure estimating the average price of consumer goods and services purchased by households. The United States Consumer Price Index, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, is a measure estimating the average price of consumer goods and services in the United States.[76] It reflects inflation as experienced by consumers in their day-to-day living expenses.[77] A graph showing the U.S. CPI relative to 1982–1984 and the annual year-over-year change in CPI is shown at right.

The value of the U.S. dollar declined significantly during wartime, especially during the American Civil War, World War I, and World War II.[78] The Federal Reserve, which was established in 1913, was designed to furnish an "elastic" currency subject to "substantial changes of quantity over short periods", which differed significantly from previous forms of high-powered money such as gold, national bank notes, and silver coins.[79] Over the very long run, the prior gold standard kept prices stable—for instance, the price level and the value of the U.S. dollar in 1914 was not very different from the price level in the 1880s. The Federal Reserve initially succeeded in maintaining the value of the U.S. dollar and price stability, reversing the inflation caused by the First World War and stabilizing the value of the dollar during the 1920s, before presiding over a 30% deflation in U.S. prices in the 1930s.[80]

Under the Bretton Woods system established after World War II, the value of gold was fixed to $35 per ounce, and the value of the U.S. dollar was thus anchored to the value of gold. Rising government spending in the 1960s, however, led to doubts about the ability of the United States to maintain this convertibility, gold stocks dwindled as banks and international investors began to convert dollars to gold, and as a result the value of the dollar began to decline. Facing an emerging currency crisis and the imminent danger that the United States would no longer be able to redeem dollars for gold, gold convertibility was finally terminated in 1971 by President Nixon, resulting in the "Nixon shock".[81]

The value of the U.S. dollar was therefore no longer anchored to gold, and it fell upon the Federal Reserve to maintain the value of the U.S. currency. The Federal Reserve, however, continued to increase the money supply, resulting in stagflation and a rapidly declining value of the U.S. dollar in the 1970s. This was largely due to the prevailing economic view at the time that inflation and real economic growth were linked (the Phillips curve), and so inflation was regarded as relatively benign.[81] Between 1965 and 1981, the U.S. dollar lost two thirds of its value.[74]

In 1979, President Carter appointed Paul Volcker Chairman of the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve tightened the money supply and inflation was substantially lower in the 1980s, and hence the value of the U.S. dollar stabilized.[81]

Over the thirty-year period from 1981 to 2009, the U.S. dollar lost over half its value.[74] This is because the Federal Reserve has targeted not zero inflation, but a low, stable rate of inflation—between 1987 and 1997, the rate of inflation was approximately 3.5%, and between 1997 and 2007 it was approximately 2%. The so-called "Great Moderation" of economic conditions since the 1970s is credited to monetary policy targeting price stability.[82]

There is ongoing debate about whether central banks should target zero inflation (which would mean a constant value for the U.S. dollar over time) or low, stable inflation (which would mean a continuously but slowly declining value of the dollar over time, as is the case now). Although some economists are in favor of a zero inflation policy and therefore a constant value for the U.S. dollar,[80] others contend that such a policy limits the ability of the central bank to control interest rates and stimulate the economy when needed.[83]

Exchange rates

Historical exchange rates

| 1970[lower-roman 1] | 1980[lower-roman 1] | 1985[lower-roman 1] | 1990[lower-roman 1] | 1993 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2018[87] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro | — | — | — | — | — | 0.9387 | 1.0832 | 1.1171 | 1.0578 | 0.8833 | 0.8040 | 0.8033 | 0.7960 | 0.7293 | 0.6791 | 0.7176 | 0.6739 | 0.7178 | 0.7777 | 0.7530 | 0.7520 | 0.9015 | 0.8504 |

| Japanese yen | 357.6 | 240.45 | 250.35 | 146.25 | 111.08 | 113.73 | 107.80 | 121.57 | 125.22 | 115.94 | 108.15 | 110.11 | 116.31 | 117.76 | 103.39 | 93.68 | 87.78 | 79.70 | 79.82 | 97.60 | 105.74 | 121.05 | 111.130 |

| Pound sterling | 8s 4d =0.4167 | 0.4484[lower-roman 2] | 0.8613[lower-roman 2] | 0.6207 | 0.6660 | 0.6184 | 0.6598 | 0.6946 | 0.6656 | 0.6117 | 0.5456 | 0.5493 | 0.5425 | 0.4995 | 0.5392 | 0.6385 | 0.4548 | 0.6233 | 0.6308 | 0.6393 | 0.6066 | 0.6544 | 0.7454 |

| Swiss franc | 4.12 | 1.68 | 2.46[88] | 1.39 | 1.48 | 1.50 | 1.69 | 1.69 | 1.62 | 1.40 | 1.24 | 1.15 | 1.29 | 1.23 | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.98 |

| Canadian dollar[89] | 1.081 | 1.168 | 1.321 | 1.1605 | 1.2902 | 1.4858 | 1.4855 | 1.5487 | 1.5704 | 1.4008 | 1.3017 | 1.2115 | 1.1340 | 1.0734 | 1.0660 | 1.1412 | 1.0298 | 0.9887 | 0.9995 | 1.0300 | 1.1043 | 1.2789 | 1.2842 |

| Mexican peso[90] | 0.01250–0.02650[lower-roman 3] | 2.80[lower-roman 3] | 2.67[lower-roman 3] | 2.50[lower-roman 3] | 3.1237 | 9.553 | 9.459 | 9.337 | 9.663 | 10.793 | 11.290 | 10.894 | 10.906 | 10.928 | 11.143 | 13.498 | 12.623 | 12.427 | 13.154 | 12.758 | 13.302 | 15.837 | 19.911 |

| Renminbi yuan[91] | 2.46 | 1.7050 | 2.9366 | 4.7832 | 5.7620 | 8.2783 | 8.2784 | 8.2770 | 8.2771 | 8.2772 | 8.2768 | 8.1936 | 7.9723 | 7.6058 | 6.9477 | 6.8307 | 6.7696 | 6.4630 | 6.3093 | 6.1478 | 6.1620 | 6.2840 | 6.383 |

| Pakistani rupee | 4.761 | 9.9 | 15.9284 | 21.707 | 28.107 | 51.9 | 51.9 | 63.5 | 60.5 | 57.75 | 57.8 | 59.7 | 60.4 | 60.83 | 67 | 80.45 | 85.75 | 88.6 | 90.7 | 105.477 | 100.661 | 104.763 | 139.850 |

| Indian rupee | 7.56 | 8.000 | 12.38 | 16.96 | 31.291 | 43.13 | 45.00 | 47.22 | 48.63 | 46.59 | 45.26 | 44.00 | 45.19 | 41.18 | 43.39 | 48.33 | 45.65 | 46.58 | 53.37 | 58.51 | 62.00 | 64.1332 | 68.11 |

| Singapore dollar | — | — | 2.179 | 1.903 | 1.6158 | 1.6951 | 1.7361 | 1.7930 | 1.7908 | 1.7429 | 1.6902 | 1.6639 | 1.5882 | 1.5065 | 1.4140 | 1.4543 | 1.24586 | 1.2565 | 1.2492 | 1.2511 | 1.2665 | 1.3748 | 1.343 |

Current exchange rates

| Current USD exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY RUB INR CNY |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY RUB INR CNY |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY RUB INR CNY |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY RUB INR CNY |

| From fxtop.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY RUB INR CNY |

See also

Notes

- Alongside East Timor centavo coins

- Alongside Ecuadorian centavo coins

- Alongside Panamanian balboa coins

- The letter "P" is used for the Philadelphia mint mark on all coins (except cents) released from 1980 onward. Before this it had only been used on silver Jefferson nickels from 1942 to 1945.

- Between 1973 and 1986 there was no mint mark (these coins are indistinguishable from coins produced at the Philadelphia Mint from 1973 to 1980); after 1988 the letter "W" was used for coinage, except for the 2009 Ultra High Relief Double Eagle.

- It is now the home of the Nevada State Museum, which still strikes commemorative medallions with the "CC" mint mark (most recently in 2014 commemorating the Nevada Sesquicentennial), using the former mint's original coin press.

- Although the mint mark "D" has been used by two separate mints, it is easy to distinguish between the two, as any 19th‑century coinage is Dahlonega, and any 20th- or 21st‑century coins are Denver.

- During the period in which this mint branch was operational, The Philippines was an insular territory and then commonwealth of the U.S.; it was the first (and to date only) U.S. branch mint located outside the Continental United States.

- The letter "M" was used for the Manila mint mark on all coins released from 1925 onward; before this it had produced its coins with no mintmark.

- During the Civil War, this mint operated under the control of the State of Louisiana (February 1861) and the Confederate States of America (March 1861) until it ran out of bullion later in that year; some Half Dollars have been identified as being the issue of the State of Louisiana and the Confederacy.

- Obverse

- Reverse

- Mexican peso values prior to 1993 revaluation

- 1970–1992. 1980 derived from AUD–USD=1.1055 and AUD–GBP=0.4957 at end of Dec 1979: 0.4957/1.1055=0.448394392; 1985 derived from AUD–USD=0.8278 and AUD–GBP=0.7130 at end of Dec 1984: 0.7130/0.8278=0.861319159.

- Value at the start of the year

References

- "Coinage Act of 1792" (PDF). United States Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2004. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- "Central Bank of Timor-Leste". Retrieved March 22, 2017.

The official currency of Timor-Leste is the United States dollar, which is legal tender for all payments made in cash.

- "Ecuador". CIA World Factbook. October 18, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

The dollar is legal tender

- "El Salvador". CIA World Factbook. October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

The US dollar became El Salvador's currency in 2001

- "Zimbabwe". CIA World Factbook. June 30, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

The US dollar was adopted as legal currency in 2009

Used alongside several other currencies. - "FAQs". BOARD OF GOVERNORS of the FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM. October 8, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

All U.S. currency remains legal tender, regardless of when it was issued.

- "Legal Tender Status". U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY. January 4, 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

United States notes serve no function that is not already adequately served by Federal Reserve notes. As a result, the Treasury Department stopped issuing United States notes, and none have been placed into circulation since January 21, 1971.

- 12 U.S.C. § 418

- "Nixon Ends Convertibility of US Dollars to Gold and Announces Wage/Price Controls". Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "Is U.S. currency still backed by gold?". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "The Implementation of Monetary Policy – The Federal Reserve in the International Sphere" (PDF). Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Cohen, Benjamin J. 2006. The Future of Money, Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11666-0.

- Agar, Charles. 2006. Vietnam, (Frommer's). ISBN 0-471-79816-9. p. 17: "the dollar is the de facto currency in Cambodia."

- "How much U.S. currency is in circulation?". Federal Reserve. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- "Definition of "Greenback " in Forex Trading". Forex trading charts BV. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- Scutt, David (June 3, 2019). "The Australian dollar is grinding higher as expectations for rate cuts from the US Federal Reserve build". Business Insider. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- Tappe, Anneken (August 9, 2018). "New Zealand dollar leads G-10 losers as greenback gains strengt". MarketWatch. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- "UPDATE 1-South Africa's rand firms against greenback, stocks rise". Reuters. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- "Why rupee is once again under pressure". Business Today. April 22, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section 8. para. 5.

- Denominations, specifications, and design of coins. 31 U.S.C. § 5112.

- U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section 9. para. 7.

- Reports. 31 U.S.C. § 331.

- "Financial Report of the United States Government" (PDF). Department of the Treasury. 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- U.S. Congress. 1792. Coinage Act of 1792. 2nd Congress, 1st Session. Sec. 9, ch. 16. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Fitzpatrick, John C., ed. (1934). "TUESDAY, AUGUST 8, 1786". Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789. XXXI: 1786: 503–505. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- Peters, Richard, ed. (1845). "SECOND CONGRESS. Sess. I. Ch. 16". The Public Statues at Large of the United States of America, etc. etc. 1: 246–251. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "Mills Currency". Past & Present. Stamp and Coin Place Blog. September 26, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- Langland, Connie (May 27, 2015). "What is a millage rate and how does it affect school funding?". WHYY. PBS and NPR. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- Mehl, B. Max. "United States $50.00 Gold Pieces, 1877", in Star Rare Coins Encyclopedia and Premium Catalogue (20th edition, 1921)

- "Ask US." National Geographic. June 2002. p. 1.

- "Dutch Colonial – Lion Dollar". Coins.lakdiva.org. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "etymologiebank.nl". etymologiebank.nl. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Julian, R.W. (2007). "All About the Dollar". Numismatist: 41.

- "Buck". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "Paper Money Glossary". Littleton Coin Company. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Cajori, Florian ([1929]1993). A History of Mathematical Notations (Vol. 2). New York: Dover, 15–29. ISBN 0-486-67766-4

- Aiton, Arthur S.; Wheeler, Benjamin W. (1931). "The First American Mint". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 11 (2). p. 198 and note 2 on p. 198. JSTOR 2506275.

- Nussbaum, Arthur (1957). A History of the Dollar. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 56.

The dollar sign, $, is connected with the peso, contrary to popular belief, which considers it to be an abbreviation of 'U.S.' The two parallel lines represented one of the many abbreviations of 'P,' and the 'S' indicated the plural. The abbreviation '$.' was also used for the peso, and is still used in Argentina.

- "U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing - FAQs". www.bep.gov.

- Rand, Ayn. [1957] 1992. Atlas Shrugged. Signet. p. 628.

- James, James Alton (1970) [1937]. Oliver Pollock: The Life and Times of an Unknown Patriot. Freeport: Books for Libraries Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-8369-5527-9.

- "The Lion Dollar: Introduction". Coins.nd.edu. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Mint, U.S. "Coinage Act of 1792". U.S. treasury.

- See .

- "United States Dollar". OANDA. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "Engraving and printing currency and security documents:Article b". Legal Information Institute. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- Matt Soniak (July 22, 2011). "On the Money: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Coin Portraits". Mental Floss. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Newman, Eric P. (1990). The Early Paper Money of America (3 ed.). Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 17. ISBN 0-87341-120-X.

- Wright, Robert E. (2008). One Nation Under Debt: Hamilton, Jefferson, and the History of What We Owe. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-0-07-154393-4.

- Christian Zappone (July 18, 2006). "Kill-the-penny bill introduced". CNN Money. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Weinberg, Ali (February 19, 2013). "Penny pinching: Can Obama manage elimination of one-cent coin?". NBC News. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "IRS Court Case Shakes the Foundations of the Debt Money System". Beyondmoney.net. November 8, 2007. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "2015 $100 American Liberty High Relief Gold Coin Photos". July 31, 2015.

- "The United States Mint Coins and Medals Program". Department of the Treasury. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "Section 13 of the Coinage Act of 1792". Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Anderson, Gordon T. 25 April 2005. "Congress tries again for a dollar coin." CNN Money.

- "Report to the Subcommittee on Treasury and General Government, Committee on Appropriations, U.S. Senate" (PDF). USGAO. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Pub. L. No. 109-145, 119 Stat. 2664 (December 22, 2005).

- "United States Mint Releases 2012 Presidential $1 Four–Coin Set on June 26". Usmint.com. June 19, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Godless Dollars

- "USPaperMoney.Info: Series 2017A $1". www.uspapermoney.info.

- "Paragraph 2 of Section 8 of Article 1 of the United States Constitution". Topics.law.cornell.edu. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "Section 411 of Title 12 of the United States Code". Law.cornell.edu. June 22, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "Section 5103 of Title 31 of the United States Code". Law.cornell.edu. August 6, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "Section 5115 of Title 31 of the United States Code". Law.cornell.edu. August 6, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- See Federal Reserve Note for details and references

- "St. Louis Adjusted Monetary Base". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "The Federal Reserve's Beige Book". The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Davies, Phil. "Right on Target". Retrieved October 17, 2018.

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

- "Open Market Operations". Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

Open market operations enable the Federal Reserve to affect the supply of reserve balances in the banking system.

- "Fact Sheets: Currency & Coins". United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "Section 9 of the Coinage Act of 1792". Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- "Measuring Worth – Purchasing Power of Money in the United States from 1774 to 2010". Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- Olivier Blanchard (2000). Macroeconomics (2nd ed.), Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-013306-X

- "Consumer Price Index Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- "Consumer Price Index Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Milton Friedman, Anna Jacobson Schwartz. A monetary history of the United States, 1867–1960. p. 546. ISBN 978-0691003542.

- Friedman 189–190

- "Central Banking—Then and Now". Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- "Controlling Inflation: A Historical Perspective" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2010. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- "Monetary Credibility, Inflation, and Economic Growth". Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- "U.S. Monetary Policy: The Fed's Goals". Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- U.S. Federal Reserve: Last 4 years, 2009–2012, 2005–2008, 2001–2004, 1997–2000, 1993–1996; Reserve Bank of Australia: 1970–present

- 2004–present

- "FRB: Foreign Exchange Rates – G.5A; Release Dates". Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- "Historical Exchange Rates Currency Converter - TransferMate". www.transfermate.com.

- "Exchange Rates Between the United States Dollar and the Swiss Franc." Measuring Worth. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- 1977–1991

- 1976–1991

- 1974–1991, 1993–1995

Further reading

- Prasad, Eswar S. (2014). The Dollar Trap: How the U.S. Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16112-9.

External links

- U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing

- U.S. Currency and Coin Outstanding and in Circulation

- American Currency Exhibit at the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank

- Relative values of the U.S. dollar, from 1774 to present

- Historical Currency Converter

- Summary of BEP Production Statistics