Great Seal of the United States

The Great Seal is a principal national symbol of the United States. The phrase is used both for the physical seal itself, which is kept by the United States Secretary of State, and more generally for the design impressed upon it. The obverse of the Great Seal depicts the national coat of arms of the United States.[1]

First used in 1782, the seal is used to authenticate certain documents issued by the federal government of the United States. Since 1935, both sides of the Great Seal have appeared on the reverse of the one-dollar bill. The coat of arms is used on official documents – including United States passports – military insignia, embassy placards, and various flags. The Seal of the President of the United States is directly based on the Great Seal, and its elements are used in numerous government agency and state seals.

Today's official versions from the Department of State are largely unchanged from the 1885 designs. The current rendering of the reverse was made by Teagle & Little of Norfolk, Virginia, in 1972. It is nearly identical to previous versions, which in turn were based on Lossing's 1856 version.[2][3]

Obverse

| Coat of arms of the United States | |

|---|---|

Greater version | |

| Versions | |

Escutcheon-only version | |

.svg.png) Monochrome (hatched) greater version | |

.svg.png) Monochrome (hatched) escutcheon-only version | |

| Armiger | United States of America |

| Adopted | 1782 |

| Crest | A glory Or, breaking through a cloud proper, surrounding an azure field bearing a constellation of thirteen stars argent |

| Blazon | Paleways of 13 pieces, argent and gules; a chief, azure |

| Supporter | A bald eagle proper displayed, bearing in its dexter talon an olive branch, in its sinister talon thirteen arrows, and in its beak a scroll bearing the motto |

| Motto | E pluribus unum "Out of many, one" |

| Use | On treaties, commissions, letterheads, license plates, embassies, agency seals and passports |

The obverse (or front) of the seal displays the coat of arms of the United States.

The colours (tinctures) of the coat of arms are either reproduced directly, or represented monochromatically by means of heraldic hatching. The latter applies when the seal is affixed to paper.

The 1782 resolution of Congress adopting the arms, still in force, legally blazoned the shield as "Paleways of 13 pieces, argent and gules; a chief, azure." As the designers recognized, this is a technically incorrect blazon under traditional English heraldic rules, since in English practice a vertically striped shield would be described as "paly", not "paleways", and it would not have had an odd number of stripes. A more technically proper blazon would have been argent, six pallets gules ... (six red stripes on a white field), but the phrase used was chosen to preserve the reference to the 13 original states.

The escutcheon (shield) bears resemblance to the American flag, with two exceptions in particular:

- The blue chief contains no stars (although certain derivative arms do, e.g. the chief of the arms of the United States Senate).

- The outermost stripes are white, not red, to avoid violation of the rule of tincture, as the chief is blue.

The supporter of the shield is a bald eagle with its wings outstretched (or "displayed", in heraldic terms). From the eagle's perspective, it holds a bundle of 13 arrows in its left talon (referring to the 13 original states), and an olive branch in its right talon, together symbolizing that the United States has "a strong desire for peace, but will always be ready for war." (see Olive Branch Petition). Although not specified by law, the olive branch is usually depicted with 13 leaves and 13 olives, again representing the 13 original states. The eagle has its head turned towards the olive branch, on its right side, to symbolize a preference for peace.[4] In its beak, the eagle clutches a scroll with the motto E pluribus unum ("Out of Many, One"). Over its head there appears a "glory" with 13 mullets (stars) on a blue field.

The primary official explanation of the symbolism of the great seal was given by Charles Thomson upon presenting the final design for adoption by Congress. He wrote:

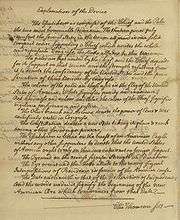

The Escutcheon is composed of the chief & pale, the two most honorable ordinaries. The Pieces, paly, represent the several states all joined in one solid compact entire, supporting a Chief, which unites the whole & represents Congress. The Motto alludes to this union. The pales in the arms are kept closely united by the chief and the Chief depends upon that union & the strength resulting from it for its support, to denote the Confederacy of the United States of America & the preservation of their union through Congress. The colours of the pales are those used in the flag of the United States of America; White signifies purity and innocence, Red, hardiness & valor, and Blue, the colour of the Chief signifies vigilance, perseverance & justice. The Olive branch and arrows denote the power of peace & war which is exclusively vested in Congress. The Constellation denotes a new State taking its place and rank among other sovereign powers. The Escutcheon is born on the breast of an American Eagle without any other supporters to denote that the United States of America ought to rely on their own Virtue.[5]

Thomson took the symbolism for the colors from Elements of Heraldry, by Antoine Pyron du Martre, which William Barton had lent him.[6] That book said that argent (white) "signifies Purity, Innocence, Beauty, and Genteelness", gules (red) "denotes martial Prowess, Boldness, and Hardiness", and azure (blue) "signifies Justice, Perseverance, and Vigilance".[7][8][9]

A brief and official explanation of the symbolism was prepared in the form of a historical sketch (or pamphlet) of the seal of the United States, entitled, The Seal of the United States: How it was Developed and Adopted. It was written by Gaillard Hunt in 1892 under the direction of then Secretary of State James G. Blaine.[10][11] When the copyright on the pamphlet expired, Hunt expounded upon the information in more detail.[10] This was published in 1909 in a book titled The History of the Seal of the United States.[10] This work was largely based on a two-volume work written in 1897 by Charles A. L. Totten titled Our Inheritance in the Great Seal of Manasseh, the United States of America: Its History and Heraldry; and Its Signification unto the 'Great People' thus Sealed.[10] Hunt's account greatly details how the seal was chosen, containing sketches of other suggestions for a great seal which were made, such as Franklin's suggested motto "Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God", information on the illegal seal, iterations and changes that have been made to the seal, and it also includes detailed descriptions of the symbology of the great seal (such as that provided by Charles Thomson).[10]

Press

In the Department of State, the term "Great Seal" refers to a physical mechanism which is used by the department to affix the seal to official government documents. This mechanism includes not only the die (metal engraved with a raised inverse image of the seal), but also the counterdie (also known as a counter-seal), the press, and cabinet in which it is housed.[12] There have been several presses used since the seal was introduced, but none of the mechanisms used from 1782 through 1904 have survived. The seal, and apparently its press, was saved when Washington, D.C. was burned in 1814 though no one knows by whom.[13][14]

The press in use today was made in 1903 by R. Hoe & Co's chief cabinetmaker Frederick S. Betchley in conjunction with the 1904 die, with the cabinet being made of mahogany. It is marked with the contracted completion date of June 15, 1903, but delays and reworking pushed final delivery into early 1904. From 1945 to 1955, the Great Seal changed quarters almost once a year. In 1955, the seal was put on public display for the first time in a central location in the Department's main building.[15] In 1961 the Seal became the focus of the new Department Exhibit Hall, where it resides today in a glass enclosure. The enclosure remains locked at all times, even during the sealing of a document.[12][13][16]

The seal can only be affixed by an officer of the Department of State, under the authority of the Secretary of State. To seal a document, first a blank paper wafer is glued onto its front in a space provided for it. The document is then placed between the die and counterdie, with the wafer lined up between them. Holding the document with one hand, the weighted arm of the press is pulled with the other, driving the die down onto the wafer, impressing the seal in relief. When envelopes containing letters need to be sealed, the wafer is imprinted first and then glued to the sealed envelope. It is used approximately 2,000 to 3,000 times a year.[12]

Documents which require the seal include treaty ratifications, international agreements, appointments of ambassadors and civil officers, and communications from the President to heads of foreign governments. The seal was once required on presidential proclamations, and on some now-obsolete documents such as exequaturs and Mediterranean passports.[17]

The press and cabinet, made in 1903

The press and cabinet, made in 1903 Clydia Mae Richardson, who led the effort to put the seal on display, and John Foster Dulles imprint a document during the 1955 ceremony

Clydia Mae Richardson, who led the effort to put the seal on display, and John Foster Dulles imprint a document during the 1955 ceremony A seal wafer

A seal wafer The wafer is positioned over the counterdie

The wafer is positioned over the counterdie The seal is pressed down on the wafer

The seal is pressed down on the wafer The imprinted seal

The imprinted seal

The metallic die of the obverse side of the Great Seal is what actually embosses the design onto documents. These dies eventually wear down, requiring replacements to be made. The current die is the seventh engraving of the seal, and the actual design on the dies has evolved over time.

| Image | Created | Description |

|---|---|---|

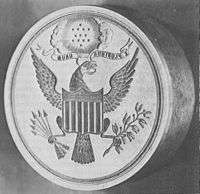

| 1782 | The first die was made of brass, and measured 2 1⁄16 inches (5.2 cm) in diameter while being one half inch (13 mm) thick.[12] It was cut sometime between June and September 1782 (i.e. between the design being accepted and its first use), although the exact date is not known.[18] The identity of the engraver is also not known; it may have been Robert Scot but Thomson may also have found a private engraver on his own.[12]

The first die depicts a relatively crude crested eagle, thin-legged and somewhat awkward. There is no fruit on the olive branch, and the engraver added a border of acanthus leaves.[12] Depicting an eagle with a crest is typical in heraldry, but is at odds with the official blazon of the seal which specifies a bald eagle (which have no crests). The blazon does not specify the arrangement of the stars (which were randomly placed in Thomson's sketch) nor the number of points; the engraver chose six-pointed stars (typical of English heraldry), and arranged them in a larger six-pointed star.[19] No drawing made by the engraver has ever been found, and it is not known if Thomson provided any.[12] This first die was used until 1841, and is now on display in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.[12] There was no die made of the reverse side of the seal (and in fact, one has never been made). The intended use was for pendant seals, which are discs of wax attached to the document by a cord or ribbon, and thus have two sides. However, the United States did not use pendant seals at the time, and there was no need for a die of the reverse.[12] In an essay published in Harper's from 1856 Bernard Lossing alluded to a version half the size for the purpose of impressing wax and paper.[20] More recent research has not been able to verify this claim, with no record of this seal being found (although the second seal committee of 1780 had recommended a half-size seal).[21] |

| 1825 | Starting with the ratification of the Treaty of Ghent, the United States began to use pendant seals on treaties, where the seal is impressed onto a separate wax disc and attached to the document with cords. Although the reverse side of the seal was designed for this purpose, a die was still not made but rather the obverse was impressed on one side only using the regular die. However, this did not conform to the European tradition of using much larger seals for treaties. To address this, Seraphim Masi of Washington D.C., was asked to design a larger seal specifically for treaties.[12] Masi produced a quite different design, showing a much more realistic (and uncrested) eagle, turned somewhat to the side. He also added fruits to the olive branch, changed the shape of the shield, and depicted the crest differently. It was 4 11⁄16 inches (11.9 cm) in diameter.[12]

These seals were transported in metallic boxes called skippets, which protected the actual wax seal from damage. The skippets themselves also were engraved with the seal design. Several skippets were made at a time, which the State Department used as needed. Usually skippets were made out of sterling silver, though for the Japanese treaty following Commodore Perry's mission a golden box was used (the ratification of that treaty, made later in 1854, had an even more elaborate and expensive seal and heavy gold skippet).[22][18] The Masi treaty die was used until 1871, almost exclusively for treaties, at which point the U.S. government discontinued the use of pendant seals. The die is also currently on display at the National Archives.[12] Masi's company made most of the skippets for almost twenty years, after which the State Department switched to nearly identical versions made by Samuel Lewis. At least one 1871 treaty seal was actually made using a Lewis skippet mold instead of the Masi die, meaning it too is technically an official die.[23] |

| 1841 | Over time, the original seal became worn and needed to be replaced. John Peter Van Ness Throop of Washington D.C. engraved a new die in 1841, which is also sometimes known as the "illegal seal" because only six arrows are shown rather than the required thirteen. Throop also chose to use five-pointed stars, though kept the six-pointed star arrangement, a change which has continued in all subsequent dies. Other changes include a more vigorous and uncrested eagle, the removal of the acanthus leaves, a general crowding of the design upward, a different shape to the shield, and fruit on the olive branch (four olives).[12]

The seal was 2 1⁄8 inches (5.4 cm) in diameter. In 1866, the first counter die was made, which is the same design in opposite relief. The paper was placed between the die and counter die, resulting in a sharper impression in the paper than from one die alone. The use of counterdies continues to this day.[12] |

| 1877 | The United States Centennial in 1876 had renewed interest in national symbols, and articles appeared noting the irregularities in the 1841 seal.[12] However, when it came time to replace the worn 1841 die, the Department of State kept the same design.

The new die was engraved by Herman Baumgarten of Washington, D.C. His version followed the 1841 die very closely, including the errors, and was the same size. The most notable differences were slightly larger stars and lettering. The workmanship on the die was relatively poor, with no impression being very clear, and it is considered the poorest of all Great Seal die.[12][24][18] Unfortunately, it was the one in use during the seal's centennial in 1882.[24] |

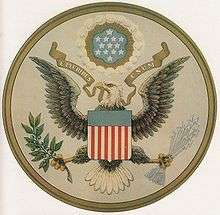

| 1885 | By early 1881 the State Department started responding to criticism of the seal,[12] resulting first in an 1882 centennial commemorative medal, and then with Secretary of State Frederick Frelinghuysen asking for funds to create a new design and dies of both the obverse and reverse on January 11, 1884, after getting estimates of the cost. Congress eventually appropriated $1,000 for those purposes on July 7, 1884.[25][26] The design contract went to Tiffany & Co.[12]

Theodore F. Dwight, Chief of the Bureau of Rolls and Library of the Department of State, supervised the process. He brought in several consultants to consider design from historical, heraldic, and artistic points of view. These included Justin Winsor, a historical scholar, Charles Eliot Norton, a Harvard professor, William H. Whitmore, author of Elements of Heraldry, John Denison Chaplin, Jr., an expert on engraving and associate editor of American Cyclopædia, the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the Unitarian minister Edward Everett Hale, and even the botanist Asa Gray to help with the olive branch.[27][26][19] Tiffany's chief designer, James Horton Whitehouse, was the artist responsible for the actual design.[12] On December 13, 1884, following much research and discussion among the group, Whitehouse submitted his designs. The result was a much more formal and heraldic look, completely different from previous dies, and has remained essentially unchanged since. The eagle is a great deal more robust and clutches the olive branch and arrows from behind. The 13 arrows were restored, in accordance with the original law, and the olive branch was depicted with 13 leaves and 13 olives. The clouds surrounding the constellation were made a complete circle for the first time.[12] The resulting die was made of steel, was 3 inches (76 mm) wide, and weighed one pound six ounces.[18] In a letter accompanying their designs, Tiffany gave their reasonings behind various elements. The eagle was made as realistic as the rules of heraldry would permit, and the scroll style was chosen to least interfere with the eagle. There were no stars in the chief (the area at the top of the shield), as is sometimes seen, as there are none specified in the blazon and thus including them would violate the rules of heraldry. Some had suggested allowing the rays of the sun to extend through the clouds, as appears to be specified in the original law and sometimes seen in other versions, but Whitehouse rejected that idea and kept with the traditional die representation. He also considered adding flowers to the olive branch, but decided against it, as "the unspecified number of flowers would be assumed to mean something when it would not".[26] Tiffany also submitted a design for the reverse of the seal, but even though Congress had ordered one a die was not created. The members of the consulting group were somewhat disparaging of the design of even the obverse, but especially critical of the reverse, and suggested not making it at all. Dwight eventually agreed and did not order the die, though he said it was "not improper" that one eventually be made.[26] To this day, there has never been an official die made of the reverse. |

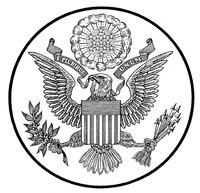

| 1904 | After only 17 years, the seal was no longer making a good impression (probably due to a worn counter die).[12] On July 1, 1902, Congress passed an act to appropriate $1250 to have the seal recut. There was some discussion among State Department officials about whether to redo the design again, but given the thought that had gone into the 1885 version, it was decided to recreate that design. Congress renewed the law on March 3, 1903, since no action had yet been taken, and this time specified that it be recut from the existing model which ended any further discussion.[26]

The die was engraved by Max Zeitler of the Philadelphia firm of Baily Banks & Biddle in 1903 (and is thus sometimes called the 1903 die), but final delivery was delayed until January 1904 due to issues with the press. There were slight differences; the impressions were sharper, the feathers more pointed, and the talons have shorter joints. Also, two small heraldic errors which had persisted on all previous seal dies were fixed:[12] the rays of the glory were drawn with dots to indicate the tincture gold, and the background of the stars was drawn with horizontal lines to indicate azure.[28] The die was first used on January 26, 1904, and was used for 26 years. All dies made since have followed exactly the same design, and in 1986 the Bureau of Engraving and Printing made a master die from which all future dies will be made.[12] The current die is the seventh and was made in 1986.[29] |

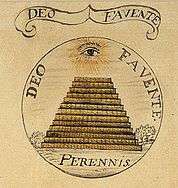

Reverse

The 1782 resolution adopting the seal blazons the image on the reverse as "A pyramid unfinished. In the zenith an eye in a triangle, surrounded by a glory, proper." The pyramid is conventionally shown as consisting of 13 layers to refer to the 13 original states. The adopting resolution provides that it is inscribed on its base with the date MDCCLXXVI (1776, the year of the United States Declaration of Independence) in Roman numerals. Where the top of the pyramid should be, the Eye of Providence watches over it. Two mottos appear: Annuit cœptis signifies that Providence has "approved of (our) undertakings."[30] Novus ordo seclorum, freely taken from Virgil,[31] is Latin for "a new order of the ages."[32] The reverse has never been cut (as a seal) but appears, for example, on the back of the one-dollar bill.

The primary official explanation of the symbolism of the great seal was given by Charles Thomson upon presenting the final design for adoption by Congress. He wrote:

The pyramid signifies Strength and Duration: The Eye over it & the Motto allude to the many signal interpositions of providence in favour of the American cause. The date underneath is that of the Declaration of Independence and the words under it signify the beginning of the new American Æra, which commences from that date.[33]

Thomson took the symbolism for the colors from Elements of Heraldry, by Antoine Pyron du Martre, which William Barton had lent him.[34] That book said that argent (white) "signifies Purity, Innocence, Beauty, and Genteelness", gules (red) "denotes martial Prowess, Boldness, and Hardiness", and azure (blue) "signifies Justice, Perseverance, and Vigilance".[35][36][37]

A brief and official explanation of the symbolism was prepared in the form of a historical sketch (or pamphlet) of the seal of the United States, entitled, The Seal of the United States: How it was Developed and Adopted. It was written by Gaillard Hunt in 1892 under the direction of then Secretary of State James G. Blaine.[10][38] When the copyright on the pamphlet expired, Hunt expounded upon the information in more detail.[10] This was published in 1909 in a book titled The History of the Seal of the United States.[10] This work was largely based on a two-volume work written in 1897 by Charles A. L. Totten titled Our Inheritance in the Great Seal of Manasseh, the United States of America: Its History and Heraldry; and Its Signification unto the 'Great People' thus Sealed.[10] Hunt's account greatly details how the seal was chosen, containing sketches of other suggestions for a great seal which were made, such as Franklin's suggested motto "Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God", information on the illegal seal, iterations and changes that have been made to the seal, and it also includes detailed descriptions of the symbology of the great seal (such as that provided by Charles Thomson).[10]

Conspiracy theories

Some conspiracy theories state that the Great Seal shows a sinister influence by Freemasonry in the founding of the United States. Such theories usually claim that the Eye of Providence (found, in the Seal, above the pyramid) is a common Masonic emblem, and that the Great Seal was created by Freemasons.[39] These claims, however, misstate the facts.

While the Eye of Providence is today a common Masonic motif, this was not the case during the 1770s and 1780s (the decades when the Great Seal was being designed and approved). According to David Barrett, a Masonic researcher, the Eye seems to have been used only sporadically by the Masons in those decades, and was not adopted as a common Masonic symbol until 1797, several years after the Great Seal of the United States had already been designed.[40] The Eye of Providence was, on the other hand, a fairly common Christian motif throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and was commonly used as such in Europe as well as America throughout the 18th century.[41][42] It is still found in Catholic, Orthodox, and even some Protestant churches, and it symbolises the Holy Trinity (the triangle) and God's omniscience (the eye) surrounded by rays of glory, denoting God's divinity.

Furthermore, contrary to the claims of these conspiracy theories, the Great Seal was not created by Freemasons.[43] While Benjamin Franklin was a Mason, he was the only member of any of the various Great Seal committees definitively known to be so, and his ideas were not adopted.[44] Of the four men whose ideas were adopted, neither Charles Thomson, Pierre Du Simitière nor William Barton were Masons and, while Francis Hopkinson has been alleged to have had Masonic connections, there is no firm evidence to support the claim.[45][46][47]

Genesis

On July 4, 1776, the same day that independence from Great Britain was declared by the thirteen colonies, the Continental Congress named the first committee to design a Great Seal, or national emblem, for the country. Similar to other nations, the United States needed an official symbol of sovereignty to formalize and seal (or sign) international treaties and transactions. It took six years, three committees, and the contributions of fourteen men before the Congress finally accepted a design (which included elements proposed by each of the three committees) in 1782.[12]

First committee

The first committee consisted of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams. While they were three of the five primary authors of the Declaration of Independence, they had little experience in heraldry and sought the help of Pierre Eugene du Simitiere, an artist living in Philadelphia who would later also design the state seals of Delaware and New Jersey and start a museum of the Revolutionary War. Each of these men proposed a design for the seal.

Franklin chose an allegorical scene from Exodus, described in his notes as "Moses standing on the Shore, and extending his Hand over the Sea, thereby causing the same to overwhelm Pharaoh who is sitting in an open Chariot, a Crown on his Head and a Sword in his Hand. Rays from a Pillar of Fire in the Clouds reaching to Moses, to express that he acts by Command of the Deity." Motto, "Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God." Jefferson suggested a depiction of the Children of Israel in the wilderness, led by a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night for the front of the seal; and Hengest and Horsa, the two brothers who were the legendary leaders of the first Anglo-Saxon settlers in Britain, for the reverse side of the seal. Adams chose a painting known as the "Judgment of Hercules" where the young Hercules must choose to travel either on the flowery path of self-indulgence or the rugged, more difficult, uphill path of duty to others and honor to himself.[48]

In August 1776, Du Simitière showed his design, which was more along conventional heraldic lines. The shield had six sections, each representing "the Countries from which these States have been peopled" (England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Germany, and Holland), surrounded by the initials of all thirteen states. The supporters were a female figure representing Liberty holding an anchor of hope and a spear with a cap, and on the other side an American soldier holding a rifle and tomahawk. The crest was the "Eye of Providence in a radiant Triangle whose Glory extends over the Shield and beyond the Figures", and the motto E Pluribus Unum (Out of Many, One) in a scroll at the bottom.[49]

On August 20, 1776, the committee presented their report to Congress. The committee members chose Du Simitière's design, though it was changed to remove the anchor of hope and replace the soldier with Lady Justice holding a sword and a balance. Surrounding the main elements was the inscription "Seal of the United States of America MDCCLXXVI". For the reverse, Franklin's design of Moses parting the Red Sea was used. Congress was however not impressed, and on the same day ordered that the report "lie on the table", ending the work of the committee.[50]

While the designs in their entirety were not used, the E Pluribus Unum motto was chosen for the final seal, and the reverse used the Roman numeral for 1776 and the Eye of Providence. Jefferson also liked Franklin's motto so much, he ended up using it on his personal seal.[48]

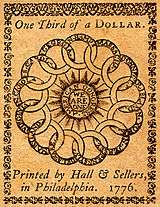

The motto was almost certainly taken from the title page of Gentleman's Magazine, a monthly magazine published in London which had used it from its first edition in 1731, and was well known in the colonies.[12] The motto alluded to the magazine being a collection of articles obtained from other newspapers, and was used in most of its editions until 1833. The motto was taken in turn from Gentleman's Journal, a similar magazine which ran briefly from 1692 to 1694. While variants turn up in other places (for example a poem often ascribed to Virgil called Moretum contains the phrase E Pluribus Unus), this is the oldest known use of the exact phrase.[51][52] Another source was some of the Continental currency issued earlier in 1776; these were designed by Franklin and featured the motto We Are One surrounded by thirteen rings, each with the name of a colony.[53][54] This design is echoed in the seal submitted by the first committee, and the motto was quite possibly a Latin version of this concept.[52]

The Eye of Providence had been a well-known classical symbol of the deity since at least the Renaissance, which Du Simitiere was familiar with.[41][18]

Second committee

For three and a half years no further action was taken, during which time the Continental Congress was forced out of Philadelphia before returning in 1778. On March 25, 1780, a second committee to design a great seal was formed, which consisted of James Lovell, John Morin Scott, and William Churchill Houston. Like the first committee, they sought the help of someone more experienced in heraldry, this time Francis Hopkinson, who did most of the work.[55]

Hopkinson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, designed the American flag,[56] and also helped design state and other government seals. He made two similar proposals, each having an obverse and reverse side, with themes of war and peace.[49]

Hopkinson's first design had a shield with thirteen diagonal red and white stripes, supported on one side by a figure bearing an olive branch and representing peace, and on the other an Indian warrior holding a bow and arrow, and holding a quiver. The crest was a radiant constellation of thirteen stars. The motto was Bello vel pace paratus, meaning "prepared in war or in peace". The reverse, in Hopkinson's words, was "Liberty is seated in a chair holding an olive branch and her staff is topped by a Liberty cap. The motto 'Virtute perennis' means 'Everlasting because of virtue.' The date in Roman numerals is 1776."[49][55]

In his second proposal, the Indian warrior was replaced by a soldier holding a sword, and the motto was shortened to Bello vel paci, meaning "For war or for peace".[55]

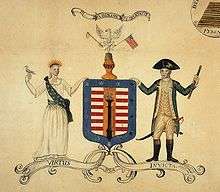

The committee chose the second version, and reported back to Congress on May 10, 1780, six weeks after being formed. Their final blazon, printed in Congress journals on May 17, was: "The Shield charged on the Field Azure with 13 diagonal stripes alternate rouge and argent. Supporters; dexter, a Warriour holding a Sword; sinister, a Figure representing Peace bearing an Olive Branch. The Crest; a radiant Constellation of 13 Stars. The motto, Bella vel Paci."[49] Once again, Congress did not find the result acceptable.[12] They referred the matter back to the committee, which did no further work on the matter.[49]

As with the first design, several elements were eventually used in the final seal; the thirteen stripes on the shield with their colors, the constellation of stars surrounded by clouds, the olive branch, and the arrows (from Hopkinson's first proposal).[12] Hopkinson had previously used the constellation and clouds on a $40 Continental currency note he designed in 1778. The same note also used an Eye of Providence, taken from the first committee's design.[54]

The shield of the Great Seal has seven white stripes and six red ones—essentially, a white background with six red stripes. Hopkinson incorporated this stripe arrangement into the Great Seal from the Flag of the United States that he had designed. Hopkinson also designed a seal for the Admiralty (Navy), which incorporated a chevron consisting of seven red stripes and six white ones. The seven red stripes in his Admiralty seal reflected the number of red stripes in his Naval flag. When Hopkinson designed these flags, he was running the Navy as chairman of the Continental Navy Board.[57]

Third committee

After two more years, Congress formed a third committee on May 4, 1782, this time consisting of John Rutledge, Arthur Middleton, and Elias Boudinot. Arthur Lee replaced Rutledge, although he was not officially appointed. As with the previous two committees, most of the work was delegated to a heraldic expert, this time 28-year-old William Barton.[12][58]

Barton drew a design very quickly, using a rooster on the crest, but it was much too complex. No drawing of this design seems to have survived.[49][58]

Barton then came up with another design, which the committee submitted back to Congress on May 9, 1782, just five days after being formed. This time, the figures on each side of the shield were the "Genius of the American Confederated Republic" represented by a maiden, and on the other side an American warrior. At the top is an eagle and on the pillar in the shield is a "Phoenix in Flames". The mottos were In Vindiciam Libertatis (In Defense of Liberty) and Virtus sola invicta (Only virtue unconquered).[58]

For the reverse, Barton used a pyramid of thirteen steps, with the radiant Eye of Providence overhead, and used the mottos Deo Favente ("With God favoring") and Perennis (Everlasting).[58] The pyramid had come from another Continental currency note designed in 1778 by Hopkinson, this time the $50 note, which had a nearly identical pyramid and the motto Perennis.[58] Barton had at first specified "on the Summit of it a Palm Tree, proper," with the explanation that "The Palm Tree, when burnt down to the very Root, naturally rises fairer than ever," but later crossed it out and replaced it with the Eye of Providence, taken from the first committee's design.[59]

Congress again took no action on the submitted design.

Final design

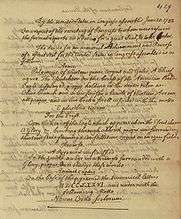

On June 13, 1782, the Congress turned to its Secretary Charles Thomson, and provided all material submitted by the first three committees.[12] Thomson was 53 years old, and had been a Latin master at a Philadelphia academy.[60] Thomson took elements from all three previous committees, coming up with a new design which provided the basis for the final seal.[12]

Thomson used the eagle—this time specifying an American bald eagle—as the sole supporter on the shield. The shield had thirteen stripes, this time in a chevron pattern, and the eagle's claws held an olive branch and a bundle of thirteen arrows. For the crest, he used Hopkinson's constellation of thirteen stars. The motto was E Pluribus Unum, taken from the first committee, and was on a scroll held in the eagle's beak.[12][60]

An eagle holding symbols of war and peace has a long history, and also echoed the second committee's themes. Franklin owned a 1702 emblem book, which included an eagle with olive branch and arrows near its talons, which may have been a source for Thomson.[51] The arrows also mirror those in the arms of the Dutch Republic, the only country in Europe with a representative government at the time, which depicted a lion holding seven arrows representing their seven provinces.[50][51] State currency may have provided further inspiration; a 1775 South Carolina bill showed a bundle of 13 arrows and a 1775 Maryland note depicted a hand with an olive branch of 13 leaves.[26]

For the reverse, Thomson essentially kept Barton's design, but re-added the triangle around the Eye of Providence and changed the mottos to Annuit Cœptis and Novus Ordo Seclorum.[60] Thomson sent his designs back to Barton, who made some final alterations. The stripes on the shield were changed again, this time to "palewise" (vertical), and the eagle's wing position was changed to "displayed" (wingtips up) instead of "rising". Barton also wrote a more properly heraldic blazon.[12]

The design was submitted to Congress on June 20, 1782, and was accepted the same day. Thomson included a page of explanatory notes, but no drawing was submitted. This remains the official definition of the Great Seal today.[12]

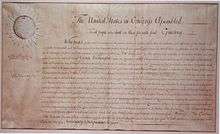

The first brass die was cut sometime between June and September, and placed in the State House in Philadelphia. It was first used by Thomson on September 16, 1782, to verify signatures on a document which authorized George Washington to negotiate an exchange of prisoners.

Charles Thomson, as the Secretary of Congress, remained the keeper of the seal until the Federal government was formed in 1789.[12] On July 24, 1789, President Washington asked Thomson to deliver the seal to the Department of Foreign Affairs in the person of Roger Alden, who kept it until the Department of State was created.[26] All subsequent Secretaries of State have been responsible for applying the Seal to diplomatic documents.

On September 15, 1789, the United States Congress ordered "that the seal heretofore used by the United States in Congress assembled, shall be, and hereby is declared to be, the seal of the United States."[1][61]

The final design was a combination of elements provided by all three committees:

- First committee

- E Pluribus Unum

- Eye of Providence in a triangle

- 1776 in Roman numerals

- Second committee

- Thirteen red and white stripes and blue chief on shield

- Constellation of 13 stars, surrounded by clouds and glory

- War and peace theme, including olive branch and (on first draft) arrows

- Third committee

- Eagle (though not a bald eagle)

- Unfinished pyramid

- Overall design of the reverse

- Charles Thomson

- Overall design of the obverse

- Bald eagle

- Annuit Cœptis

- Novus Ordo Seclorum

- William Barton

- Vertical stripes on shield

- Position of eagle's wings

Notable depictions

The Great Seal very quickly became a popular symbol of the country. Combined with the heraldic tradition of artistic freedom so long as the particulars of the blazon are followed, a wide variety of official and unofficial emblazonments appeared, especially in the first hundred years. This is evident even in the different versions of the seal die. The quality of the 1885 design, coupled with a spirit of bureaucratic standardization that characterized that era, has driven most of these out of official use.[19][62]

See also

References

- "The Arms of the United States: Criticisms and Rebuttals". The American Heraldry Society. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- The Eagle and the Shield, p. xxxvii

- The vector version of the obverse at the top of this article was taken from U.S. government publications, while the vector reverse was made by a Wikipedia contributor and patterned after this official one.

- "A Turn of the Head". snopes.com.

- As quoted by MacArthur, John D. "Explanation of the Great Seal's Symbolism". greatseal.com.

- Patterson, Richard Sharpe; Dougall, Richardson (1978) [1976 i.e. 1978]. The Eagle and the Shield: A History of the Great Seal of the United States. Department and Foreign Service series; 161 Department of State publication; 8900. Washington : Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, Dept. of State : for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 80–81. LCCN 78602518. OCLC 4268298.

- Pyron du Martre, Antoine (Pen name: Mark Anthony Porny) (1771). The Elements of Heraldry. T. Carnan and F. Newbery, Jr. Glossary entry: Argent

- Pyron du Martre, Antoine (Pen name: Mark Anthony Porny) (1771). The Elements of Heraldry. T. Carnan and F. Newbery, Jr. Glossary entry: Gules

- Pyron du Martre, Antoine (Pen name: Mark Anthony Porny) (1771). The Elements of Heraldry. T. Carnan and F. Newbery, Jr. Glossary entry: Azure

- Hunt, Gaillard. "The History of the Seal of the United States". Washington, D.C.: Department of State, 1909 1st Ed. Page 5.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Uncle Sam Has Seal Maker in the Library of Congress". Magazine. The Washington Herald. March 2, 1913. p. 3 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress.

- Bureau of Public Affairs. "The Great Seal of the United States" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- "Keeping the Seal in Good Hands". U.S. Diplomacy Center. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- The Eagle and the Shield, pp. 164–165

- The Eagle and the Shield, p. 322

- "Great Seal Fact Sheet". Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- "Redefining the Seal's Use". and "Using the Seal as the Nation Expands". U.S. Diplomacy Center. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- Totten, C.A.L. (1897). The Seal of History. New Haven, Connecticut: The Our Race Publishing Co.

- McMillan, Joseph. "The Arms of the USA: Artistic Expressions". americanheraldry.org. Archived from the original on June 24, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- Lossing, Benson J. (July 1856). "Great Seal of the United States". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 13 (74): 184–5.

Congress then ordered a seal half the size of the great one, to impress wax and paper, as you now see it upon this commission signed by my old and trusty friend, Charles Thomson.

- The Eagle and the Shield, p. 564 See footnote 29. "No evidence has been found to substantiate this statement either, although the report of the second seal committee in 1780 (which was not adopted) recommended a half-size seal."

- The Eagle and the Shield, p. 189

- The Eagle and the Shield, pp. 217–218

- The Eagle and the Shield, p. 229

- The Eagle and the Shield, pp. 246–247

- Hunt, Gaillard (1909). The History of the Seal of the United States. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State. OCLC 2569489.

- The Eagle and the Shield, pp. 236–268

- The Eagle and the Shield, p. 308

- MacArthur, John D. "Official Dies of the Great Seal of the United States". greatseal.com. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- Journals of the Continental Congress, June 20, 1782

- MacArthur, John D. "Source of NOVUS ORDO SECLORUM". greatseal.com.

- The word seclorum does not mean "secular", as one might assume, but is the genitive (possessive) plural form of the word saeculum, meaning (in this context) generation, century, or age. Saeculum did come to mean "age, world" in late, Christian, Latin, and "secular" is derived from it, through secularis. However, the adjective "secularis," meaning "worldly," is not equivalent to the genitive plural seclorum, meaning "of the ages." (Lewis and Short (1879). A Latin Dictionary: Founded on Andrews' Edition of Freund's Latin Dictionary: Revised, Enlarged, and in Great Part Rewritten by Charlton T. Lewis, PhD and Charles Short, LL.D. Oxford: Clarendon Press. s. vv.)

- As quoted by MacArthur, John D. "Explanation of the Great Seal's Symbolism". greatseal.com.

- Patterson, Richard Sharpe; Dougall, Richardson (1978) [1976 i.e. 1978]. The Eagle and the Shield: A History of the Great Seal of the United States. Department and Foreign Service series; 161 Department of State publication; 8900. Washington : Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, Dept. of State : for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 80–81. LCCN 78602518. OCLC 4268298.

- Pyron du Martre, Antoine (Pen name: Mark Anthony Porny) (1771). The Elements of Heraldry. T. Carnan and F. Newbery, Jr. Glossary entry: Argent

- Pyron du Martre, Antoine (Pen name: Mark Anthony Porny) (1771). The Elements of Heraldry. T. Carnan and F. Newbery, Jr. Glossary entry: Gules

- Pyron du Martre, Antoine (Pen name: Mark Anthony Porny) (1771). The Elements of Heraldry. T. Carnan and F. Newbery, Jr. Glossary entry: Azure

- "Uncle Sam Has Seal Maker in the Library of Congress". Magazine. The Washington Herald. March 2, 1913. p. 3 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress.

- for example: conspiracyarchive.com, and www.masoncode.com

- "Masonic Dollar?". Freemasons-freemasonry.com. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- The Eagle and the Shield, p. 531. Some examples include the Holy Trinity Column in Olomouc, Czech Republic built from 1716–1754 (seen here), the Gate of Dawn in Vilnius, built between 1503 and 1522 (seen here), the Aachen Cathedral (seen here, inscription dated 1766), the cover of a 1762 book by Giovanni Battista Morgagni, or the 1789 French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (seen here).

- "Do the Illuminati Really Exist?". Angels & Demons from the Book to the Movie FAQ. Center for Studies on New Religions. Retrieved May 25, 2009.

- "Associated Press story, Tuesday, February 12, 2008 as hosted by". Foxnews.com. February 12, 2008. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- Hodapp, Christopher; Freemasons for Dummies, Wiley Publishing, 2005, pp 155–156

- MacArthur, John D. "Is the Pyramid & Eye a Masonic Symbol on the Great Seal and Dollar Bill?". greatseal.com. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- The Eagle and the Shield, p. 529

- Design by King & Associates (www.edking.com). "the Masonic Service Association". Msana.com. Archived from the original on November 15, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- MacArthur, John D. "First Great Seal Committee: July–August 1776". greatseal.com. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- "The Arms of the USA: Development of the Design". Archived from the original on June 24, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- "Official Heraldry of the United States". Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- "The Arms of the USA: Blazon and Symbolism". Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- Totten, C.A.L. (1897). The Seal of History, Vol II. pp. 122–3.

- Jordan, Louis. "Continental Currency: February 17, 1776". University of Notre Dame. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- MacArthur, John D. "Symbols of Unity on Continental Currency". greatseal.com. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- MacArthur, John D. "Second Great Seal Committee: March 1780". greatseal.com. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- The Eagle and the Shield, pp. 34–35 "He created the American flag that Congress adopted on June 14, 1777."

- Williams, Jr., Earl P. (October 2012). "Did Francis Hopkinson Design Two Flags?" (PDF). NAVA News (216): 7–9. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- MacArthur, John D. "Third Great Seal Committee: May 1782". greatseal.com. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- MacArthur, John D. "Third Great Seal Committee Blazon". greatseal.com. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- MacArthur, John D. "The Final Design of the Great Seal: June 20, 1782". greatseal.com. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- Chap. XIV. 1 Stat. 68 from "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875". Library of Congress, Law Library of Congress. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- Anderson, Susan H. "Elements of Design in the Senate's Carpet". The Most Splendid Carpet. National Park Service. OCLC 06279577.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Seal of the United States. |

- PDF booklet from U.S. State Department, 2003 version, and 1996 version—Bureau of Public Affairs

- Webpage for the United States Department of State Traveling Exhibit on the Great Seal of the United States (available on Internet Archive as found on August 16, 2017)

- Website on the Great Seal

- Dr. Robert Hieronimus visits the Keeper of the Seal with photos of the actual die press

.svg.png)

.svg.png)