Sacagawea

Sacagawea (/səˌkɑːɡəˈwiːə/; also Sakakawea or Sacajawea; May c. 1788 – December 20, 1812 or April 9, 1884)[1][2][3] was a Lemhi Shoshone woman who, at age 16, met and helped the Lewis and Clark Expedition in achieving their chartered mission objectives by exploring the Louisiana Territory. Sacagawea traveled with the expedition thousands of miles from North Dakota to the Pacific Ocean, helping to establish cultural contacts with Native American populations in addition to her contributions to natural history.

Sacagawea | |

|---|---|

Sacagawea (right) with Lewis and Clark at the Three Forks, mural at Montana House of Representatives | |

| Born | May 1788 |

| Died | December 20, 1812 (aged 24) or April 9, 1884 (aged 95) |

| Nationality | Lemhi Shoshone |

| Other names | Sakakawea, Sacajawea |

| Known for | Accompanied the Lewis and Clark Expedition |

| Spouse(s) | Toussaint Charbonneau |

| Children |

|

Sacagawea was an important member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The National American Woman Suffrage Association of the early 20th century adopted her as a symbol of women's worth and independence, erecting several statues and plaques in her memory, and doing much to spread the story of her accomplishments.[4]

Pre-expedition

Reliable historical information about Sacagawea is very limited. She was born c. 1788 into the Agaidika ('Salmon Eater'; aka Lemhi Shoshone) tribe near Salmon, Lemhi County, which sits by the continental divide at the present-day Idaho-Montana border.[5]

In 1800, when she was about 12 years old, she and several other girls were kidnapped by a group of Hidatsa in a battle that resulted in the deaths of several Shoshone: four men, four women, and several boys. She was held captive at a Hidatsa village near present-day Washburn, North Dakota.[6]

At about age 13, she was sold into a non-consensual marriage to Toussaint Charbonneau, a Quebecois trapper living in the village who had also bought another young Shoshone, known as Otter Woman, as his wife. Charbonneau was variously reported to have purchased both girls to be his wives from the Hidatsa or to have won Sacagawea while gambling.[6]

The Lewis & Clark Expedition

The Corps of Discovery arrived near the Hidatsa villages, where Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark built Fort Mandan, to spend the winter of 1804–05. They interviewed several trappers who might be able to interpret or guide the expedition up the Missouri River in the springtime. Knowing they would need the help of Shoshone tribes at the headwaters of the Missouri, they agreed to hire Toussaint Charbonneau after discovering that his wife, Sacagawea, who was pregnant with her first child at the time, spoke Shoshone.

On November 4, 1804, Clark recorded in his journal:[7][lower-alpha 1]

[A] french man by Name Chabonah, who Speaks the Big Belley language visit us, he wished to hire & informed us his 2 Squars (squaws) were Snake Indians, we engau (engaged) him to go on with us and take one of his wives to interpret the Snake language.…

Charbonneau and Sacagawea moved into the expedition's fort a week later. Clark nicknamed her "Janey."[lower-alpha 2] Lewis recorded the birth of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau on February 11, 1805, noting that another of the party's interpreters administered crushed rattlesnake rattles in water to speed the delivery. Clark and other European-Americans nicknamed the boy "Little Pomp" or "Pompy."

In April, the expedition left Fort Mandan and headed up the Missouri River in pirogues. They had to be poled against the current and sometimes pulled from the riverbanks. On May 14, 1805, Sacagawea rescued items that had fallen out of a capsized boat, including the journals and records of Lewis and Clark. The corps commanders, who praised her quick action, named the Sacagawea River in her honor on May 20, 1805. By August 1805, the corps had located a Shoshone tribe and was attempting to trade for horses to cross the Rocky Mountains. They used Sacagawea to interpret and discovered that the tribe's chief, Cameahwait, was her brother.

Lewis recorded their reunion in his journal:[9]

Shortly after Capt. Clark arrived with the Interpreter Charbono, and the Indian woman, who proved to be a sister of the Chief Cameahwait. The meeting of those people was really affecting, particularly between Sah cah-gar-we-ah and an Indian woman, who had been taken prisoner at the same time with her, and who had afterwards escaped from the Minnetares and rejoined her nation.

And Clark in his:[10]

…The Intertrepeter [sic] & Squar who were before me at Some distance danced for the joyful Sight, and She made signs to me that they were her nation…

The Shoshone agreed to barter horses to the group and to provide guides to lead them over the cold and barren Rocky Mountains. The trip was so hard that they were reduced to eating tallow candles to survive. When they descended into the more temperate regions on the other side, Sacagawea helped to find and cook camas roots to help them regain their strength.

As the expedition approached the mouth of the Columbia River on the Pacific Coast, Sacagawea gave up her beaded belt to enable the captains to trade for a fur robe they wished to give to President Thomas Jefferson.

Clark's journal entry for November 20, 1805, reads:[11]

one of the Indians had on a roab made of 2 Sea Otter Skins the fur of them were more butifull than any fur I had ever Seen both Capt. Lewis & my Self endeavored to purchase the roab with different articles at length we precured it for a belt of blue beeds which the Squar—wife of our interpreter Shabono wore around her waste.… [sic]

When the corps reached the Pacific Ocean, all members of the expedition—including Sacagawea and Clark's black manservant York—voted on November 24 on the location for building their winter fort. In January, when a whale's carcass washed up onto the beach south of Fort Clatsop, Sacagawea insisted on her right to go see this "monstrous fish."

On the return trip, they approached the Rocky Mountains in July 1806. On July 6, Clark recorded:

The Indian woman informed me that she had been in this plain frequently and knew it well.… She said we would discover a gap in the mountains in our direction [i.e., present-day Gibbons Pass].

A week later, on July 13, Sacagawea advised Clark to cross into the Yellowstone River basin at what is now known as Bozeman Pass. Later, this was chosen as the optimal route for the Northern Pacific Railway to cross the continental divide.

While Sacagawea has been depicted as a guide for the expedition,[12] she is recorded as providing direction in only a few instances. Her work as an interpreter certainly helped the party to negotiate with the Shoshone; however, her greatest value to the mission may have been simply her presence during the arduous journey, which demonstrated the peaceful intent of the expedition.

While traveling through what is now Franklin County, Washington, in October 1805, Clark noted that "the wife of Shabono [Charbonneau] our interpetr we find reconsiles all the Indians, as to our friendly intentions a woman with a party of men is a token of peace,"[13] and that she "confirmed those people of our friendly intentions, as no woman ever accompanies a war party of Indians in this quarter" [sic].[14]

As he traveled downriver from Fort Mandan at the end of the journey, on board the pirogue near the Ricara Village, Clark wrote to Charbonneau:[15]

You have been a long time with me and conducted your Self in Such a manner as to gain my friendship, your woman who accompanied you that long dangerous and fatigueing rout to the Pacific Ocian and back diserved a greater reward for her attention and services on that rout than we had in our power to give her at the Mandans. As to your little Son (my boy Pomp) you well know my fondness of him and my anxiety to take him and raise him as my own child.… If you are desposed to accept either of my offers to you and will bring down you Son your famn [femme, woman] Janey had best come along with you to take care of the boy untill I get him.… Wishing you and your family great success & with anxious expectations of seeing my little danceing boy Baptiest I shall remain your Friend, William Clark. [sic]

— Clark to Charbonneau, August 20, 1806

Later life and death

Children

Following the expedition, Charbonneau and Sacagawea spent 3 years among the Hidatsa before accepting William Clark's invitation to settle in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1809. They entrusted Jean-Baptiste's education to Clark, who enrolled the young man in the Saint Louis Academy boarding school.[16][17] Sacagawea gave birth to a daughter, Lizette Charbonneau, sometime after 1810.[17][18] However, there is no later record of Lizette among Clark's papers. It is believed that she died in childhood.

Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau

Sacagawea's son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, continued a restless and adventurous life. He carried lifelong celebrity status as the infant who went with the explorers to the Pacific Ocean and back. When he was 18, he was befriended by a German Prince, Duke Paul Wilhelm of Württemberg, who took him to Europe. There, Jean-Baptiste spent six years living among royalty, while learning four languages and fathering a child in Germany named Anton Fries.[19]

After his infant son died, Jean-Baptiste came back from Europe in 1829 to live the life of a Western frontiersman. He became a gold miner and a hotel clerk and in 1846 led a group of Mormons to California. While in California he became a magistrate for the Mission San Luis Rey. He disliked the way Indians were treated in the Missions and left to become a hotel clerk in Auburn, California, once the center of gold rush activity.[17]

After working six years in Auburn, the restless Jean-Baptiste left in search of riches in the gold mines of Montana. He was 61 years old, and the trip was too much for him. He became ill with pneumonia and died in a remote area near Danner, Oregon, on May 16, 1866.[17]

Death

According to Bonnie "Spirit Wind-Walker" Butterfield (2010), historical documents suggest that Sacagawea died in 1812 of an unknown sickness.[17] For instance, a journal entry from 1811 by Henry Brackenridge, a fur trader at Fort Lisa Trading Post on the Missouri River, wrote that Sacagawea and Charbonneau were living at the fort.[17] Brackenrige recorded that Sacagawea "had become sickly and longed to revisit her native country."[20] Butterfield then points to the following year, 1812, where a Fort-Lisa clerk, John Luttig, recorded in his journal on December 20 that "the wife of Charbonneau, a Snake Squaw [i.e. Shoshone Indians], died of putrid fever."[20] He goes on to say that she was "aged about 25 years. She left a fine infant girl."[17] Furthermore, documents held by Clark show that her son Baptiste already had been entrusted by Charbonneau into Clark's care for a boarding school education, at Clark's insistence (Jackson, 1962).[17]

In February 1813, a few months after Luttig's journal entry, 15 men were killed in a Native attack on Fort Lisa, then located at the mouth of the Bighorn River.[20] Luttig and Sacagawea's young daughter were among the survivors. Charbonneau was mistakenly thought to have been killed at this time, but he apparently lived to at least age 76. He had signed over formal custody of his son to William Clark in 1813.[21]

As further proof that Sacagawea died in 1812, Butterfield writes:[17]

An adoption document made in the Orphans Court Records in St. Louis, Missouri, states,[18] 'On August 11, 1813, William Clark became the guardian of Tousant Charbonneau, a boy about ten years, and Lizette Charbonneau, a girl about one year old.' For a Missouri State Court at the time, to designate a child as orphaned and to allow an adoption, both parents had to be confirmed dead in court papers.

The last recorded document citing Sacagawea's existence appears in William Clark's original notes written between 1825 and 1826.[17] He lists the names of each of the expedition members and their last known whereabouts. For Sacagawea, he writes, "Se car ja we au— Dead."[16]

Some Native American oral traditions relate that, rather than dying in 1812, Sacagawea left her husband Charbonneau, crossed the Great Plains, and married into a Comanche tribe. She was said to have returned to the Shoshone in 1860 in Wyoming, where she died in 1884.[22]

Remains

The question of Sacagawea's final resting place caught the attention of national suffragists seeking voting rights for women, according to author Raymond Wilson.[23] Wilson argues that Sacagawea became a role model whom suffragettes pointed to "with pride." Wilson goes on to note:[23]

Interest in Sacajawea peaked and controversy intensified when Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard, professor of political economy at the University of Wyoming in Laramie and an active supporter of the Nineteenth Amendment, campaigned for federal legislation to erect an edifice honoring Sacajawea's death in 1884.

In 1925, Dr. Charles Eastman, a Dakota Sioux physician, was hired by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to locate Sacagawea's remains.[24] Eastman visited various Native American tribes to interview elderly individuals who might have known or heard of Sacagawea. He learned of a Shoshone woman at the Wind River Reservation with the Comanche name Porivo ('chief woman'). Some of those he interviewed said that she spoke of a long journey wherein she had helped white men, and that she had a silver Jefferson peace medal of the type carried by the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He found a Comanche woman named Tacutine who said that Porivo was her grandmother. According to Tacutine, Porivo had married into a Comanche tribe and had a number of children, including Tacutine's father, Ticannaf. Porivo left the tribe after her husband, Jerk-Meat, was killed.[24]

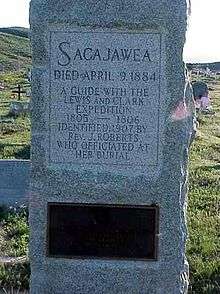

According to these narratives, Porivo lived for some time at Fort Bridger in Wyoming with her sons Bazil and Baptiste, who each knew several languages, including English and French. Eventually, she found her way back to the Lemhi Shoshone at the Wind River Reservation, where she was recorded as "Bazil's mother."[24] This woman, Porivo is believed to have died on April 9, 1884.[25]

It was Eastman's conclusion that Porivo was Sacagawea.[26] In 1963, a monument to "Sacajawea of the Shoshonis" was erected at Fort Washakie on the Wind River reservation near Lander, Wyoming, on the basis of this claim.[27]

The belief that Sacagawea lived to old age and died in Wyoming was widely disseminated in the United States through Sacajawea (1933), a biography written by University of Wyoming professor and historian Grace Raymond Hebard, which includes the professor's own 30 years of research.[28] However, critics have called Hebard's work into question,[28] as she presents a stout-hearted woman in her portrayal of Sacajawea that is "undeniably long on romance and short on hard evidence, suffering from a sentimentalization of Indian culture."[29]

Spelling of name

A long-running controversy has surrounded the correct spelling, pronunciation, and etymology of the woman's name; however, linguists working on Hidatsa since the 1870s have always considered the name's Hidatsa etymology essentially indisputable. The name is a compound of two common Hidatsa nouns: cagáàga ([tsakáàka], 'bird') and míà ([míà], 'woman'). The compound is written as Cagáàgamia ('Bird Woman') in modern Hidatsa orthography, and pronounced [tsakáàkawia] (/m/ is pronounced [w] between vowels in Hidatsa). The double /aa/ in the name indicates a long vowel, while the diacritics suggest a falling pitch pattern.

Hidatsa is a pitch-accent language that does not have stress; therefore, in the Hidatsa pronunciation all syllables in [tsaɡáàɡawia] are pronounced with roughly the same relative emphasis. However, most English speakers perceive the accented syllable (the long /aa/) as stressed. In faithful rendering of Cagáàgawia to other languages, it is advisable to emphasize the second, long syllable, rather than the last, as is common in English.[30]

The name has several spelling traditions in English. The origin of each tradition is described in the following sections.

Sacagawea

Sacagawea (/səˌkɑːɡəˈwiːə/) is the most widely-used spelling of her name, pronounced with a hard "g" sound, rather than a soft "g" or "j" sound. Lewis and Clark's original journals mention Sacagawea by name seventeen times, spelled eight different ways, each time with a "g". Clark used Sahkahgarwea, Sahcahgagwea, Sarcargahwea, and Sahcahgahweah, while Lewis used Sahcahgahwea, Sahcahgarweah, Sahcargarweah, and Sahcahgar Wea.

The spelling Sacagawea was established in 1910 by the Bureau of American Ethnology as the proper usage in government documents. It would be the spelling adopted by the U.S. Mint for use with the dollar coin, as well as the U.S. Board on Geographic Names and the National Park Service. The spelling is also used by a large number of historical scholars.[31]

Sakakawea

Sakakawea (/səˌkɑːkəˈwiːə/) is the next most widely-adopted spelling, and is the most-often accepted among specialists.[32] Proponents say the name comes from the Hidatsa tsakáka wía ('bird woman').[33][34] Charbonneau told expedition members that his wife's name meant "Bird Woman," and in May 1805 Lewis used the Hidatsa meaning in his journal:

[A] handsome river of about fifty yards in width discharged itself into the shell river… [T]his stream we called Sah-ca-gah-we-ah or bird woman's River, after our interpreter the Snake woman.

Sakakawea is the official spelling of her name according to the Three Affiliated Tribes, which include the Hidatsa, and is widely used throughout North Dakota (where she is considered a state heroine), notably in the naming of Lake Sakakawea, the extensive reservoir of Garrison Dam on the Missouri River.

The North Dakota State Historical Society quotes Russell Reid's book Sakakawea: The Bird Woman:[35]

Her Hidatsa name, which Charbonneau stated meant "Bird Woman," should be spelled "Tsakakawias" according to the foremost Hidatsa language authority, Dr. Washington Matthews. When this name is anglicized for easy pronunciation, it becomes Sakakawea, "Sakaka" meaning "bird" and "wea" meaning "woman." This is the spelling adopted by North Dakota. The spelling authorized for the use of federal agencies by the United States Geographic Board is Sacagawea. Although not closely following Hidatsa spelling, the pronunciation is quite similar and the Geographic Board acknowledged the name to be a Hidatsa word meaning "Bird Woman.

Nevertheless, Irving W. Anderson, president of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, argues:[8]

[T]he Sakakawea spelling similarly is not found in the Lewis and Clark journals. To the contrary, this spelling traces its origin neither through a personal connection with her nor in any primary literature of the expedition. It has been independently constructed from two Hidatsa Indian words found in the dictionary Ethnography and Philology of the Hidatsa Indians (1877), published by the Government Printing Office.[36] Compiled by a United States Army surgeon, Dr. Washington Matthews, 65 years following Sacagawea's death, the words appear verbatim in the dictionary as "tsa-ka-ka, noun; a bird," and "mia [wia, bia], noun; a woman.

Sacajawea

The name Sacajawea or Sacajewea (/ˌsækədʒəˈwiːə/), in contrast to the Hidatsa etymology, is said to have derived from Shoshone Saca-tzaw-meah, meaning 'boat puller' or 'boat launcher'.[8] It is the preferred spelling used by the Lemhi Shoshone people, some of whom claim that her Hidatsa captors merely reinterpreted her existing Shoshone name in their own language, and pronounced it in their own dialect[37]—they heard a name that approximated tsakaka and wia, and interpreted it as 'bird woman', substituting the hard "g/k" pronunciation for the softer "tz/j" sound that did not exist in the Hidatsa language.

The use of this spelling almost certainly originated from the use of the "j" spelling by Nicholas Biddle, who annotated the journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition for publication in 1814. This use became more widespread with the publication of the 1902 novel The Conquest: The True Story of Lewis and Clark, written by Eva Emery Dye. It is likely that Dye used Biddle's secondary source for the spelling, and her highly popular book made it ubiquitous throughout the United States (previously most non-scholars had never even heard of Sacagawea).[38]

Rozina George, great-great-great-great-granddaughter of Cameahwait, says the Agaidika tribe of Lemhi Shoshone do not recognize the spelling or pronunciation Sacagawea, and schools and other memorials erected in the area surrounding her birthplace use the spelling Sacajawea:[39]

The Lemhi Shoshone call her Sacajawea. It is derived from the Shoshone word for her name, Saca tzah we yaa. In his Cash Book, William Clark spells Sacajawea with a "J". Also, William Clark and Private George Shannon explained to Nicholas Biddle (Published the first Lewis and Clark Journals in 1814) about the pronunciation of her name and how the tz sounds more like a "j". What better authority on the pronunciation of her name than Clark and Shannon who traveled with her and constantly heard the pronunciation of her name? We do not believe it is a Minnetaree (Hidatsa) word for her name. Sacajawea was a Lemhi Shoshone not a Hidatsa.

Idaho native John Rees explored the 'boat launcher' etymology in a long letter to the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs written in the 1920s.[8] It was republished in 1970 by the Lemhi County Historical Society as a pamphlet entitled "Madame Charbonneau" and contains many of the arguments in favor of the Shoshone derivation of the name.[37][8]

The spelling Sacajawea, although widely taught until the late 20th century, is generally considered incorrect in modern academia. Linguistics professor Dr. Sven Liljeblad from the Idaho State University in Pocatello has concluded that "it is unlikely that Sacajawea is a Shoshoni word.… The term for 'boat' in Shoshoni is saiki, but the rest of the alleged compound would be incomprehensible to a native speaker of Shoshoni."[8] The spelling has subsided from general use, although the corresponding "soft j" pronunciation persists in American culture.

In popular culture

Some fictional accounts speculate that Sacagawea was romantically involved with Lewis or Clark during their expedition, however, while the journals show that she was friendly with Clark and would often do favors for him, the idea of a romantic liaison was created by novelists who wrote about the expedition much later. This fiction was perpetuated in the Western film The Far Horizons (1955).

Film and television

Several movies, both documentaries and fiction, have been made about, or featuring, Sacagawea:[40]

- The Far Horizons (1955) – played by Donna Reed

- Lewis & Clark: Great Journey West (2002) – played by Alex Rice

- Jefferson's West (2003) – played by Cedar Henry

- Journey of Sacagawea (2004)

- Bill and Meriwether's Excellent Adventure (2006) – played by Crystal Lysne

- Night at the Museum (2006) – played by Mizuo Peck

- The Spirit of Sacajawea (2007)

- Night at the Museum 2: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) – played by Mizuo Peck

- Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014) – played by Mizuo Peck

In 1967, the actress Victoria Vetri, under the name Angela Dorian, played Sacajawea in the episode "The Girl Who Walked the West" of the syndicated television series, Death Valley Days.[41]

Literature

Two early twentieth-century novels shaped much of the public perception of Sacagawea. The Conquest: The True Story of Lewis and Clark (1902), was written by American suffragist Eva Emery Dye and published in anticipation of the expedition's centennial.[42] The National American Woman Suffrage Association embraced her as a female hero, and numerous stories and essays about her appeared in ladies' journals. A few decades later, Grace Raymond Hebard published Sacajawea: Guide and Interpreter of Lewis and Clark (1933) to even greater success.[12]

Sacagawea has since become a popular figure in historical and young adult novels. In her novel Sacajawea (1984), Anna Lee Waldo explored the story of Sacajawea's returning to Wyoming 50 years after her departure. The author was well aware of the historical research supporting an 1812 death, but she chose to explore the oral tradition.

Music and theatre

- In Philip Glass's "Piano Concerto No. 2 after Lewis & Clark", the second movement is entitled "Sacagawea".

- Sacagawea is mentioned in the Schoolhouse Rock song "Elbow Room" as the guide for Lewis and Clark.[43]

- Sacagewea is referenced in Stevie Wonder's song "Black Man" from the album Songs in the Key of Life (1976).

- Tingstad & Rumbel's 1988 album Legends includes a piece entitled "Sacajawea".[44]

- Sacagawea is the name of a musical by Craig Bohmler and Mary Bracken Phillips. It was commissioned by the Willows Theatre Company in northern California and premiered at the annual John Muir Festival in the summer of 2008 at the Alhambra Performing Arts Center in Martinez, California.[45][46][47][48]

- In 2010, Italian pianist and composer Alessandra Celletti released Sketches of Sacagawea, a limited-edition tribute box set with an album and accompanying book, on Al-Kemi Lab.[49]

Other media

The Dinner Party, an artwork installation by feminist artist Judy Chicago, features a place setting for Sacagawea in Wing Three, titled American Revolution to the Women's Revolution.[50]

The first episode of the history podcast, The Broadsides, includes discussion of Sacagawea and her accomplishments during the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[51]

Memorials and honours

Sacagawea was an important member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The National American Woman Suffrage Association of the early 20th century adopted her as a symbol of women's worth and independence, erecting several statues and plaques in her memory, and doing much to spread the story of her accomplishments.[4]

In 1959, she was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[1] Likewise, in 1976, she became a Hall-of-Fame Honoree of the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame in Fort Worth, Texas.[2] In 2001, she was given the title of Honorary Sergeant, Regular Army, by then-president Bill Clinton.[52] In 2003, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[3]

USS Sacagawea, one of several United States ships named in her honor.

| Sacagawea on US Dollar coin. | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Obverse: Sacagawea with her son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, US national motto, year and Liberty on top. | Reverse: Eagle in flight, country name, face value and E pluribus unum (Out of many, one). |

| Coin popularly known as Sacagawea dollar. | |

Coinage

In 2000, the United States Mint issued the Sacagawea dollar coin in her honor, depicting Sacagawea and her son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau. Because no contemporary image of Sacagawea exists, the face on the coin was modeled on a modern Shoshone-Bannock woman named Randy'L He-dow Teton. The portrait design is unusual, as the copyrights have been assigned to and are owned by the U.S. Mint. Therefore the portrait is not in the public domain, as most US coin designs are.[53]

Geography and parks

- Lake Sakakawea in North Dakota

- Sacajawea Memorial Area, at Lemhi Pass, a National Historic Landmark managed by the National Forest Service and located on the boundary of Montana and Idaho, where visitors can hike the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) created the memorial area in 1932 to honor Sacajawea for her role in the success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[22]

- Mount Sacagawea, Fremont County, Wyoming, and the associated Sacagawea Glacier

- The Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Educational Center is a 71-acre (290,000 m2) park located in Salmon, Idaho, by the rivers and mountains of Sacajawea's homeland. It is "owned and operated by the City of Salmon, in partnership with the Bureau of Land Management, Idaho Governor's Lewis & Clark Trail Committee, Salmon-Challis National Forest, Idaho Department of Fish & Game, and numerous non-profit and volunteer organizations."[54]

- Sacagawea Heritage Trail, a bike trail in Tri-Cities, Washington

- Sacajawea Patera, a caldera on the planet Venus

- Sacajawea Peak

- Wallowa County, Oregon

- Sacagawea Park, Gallatin County, Montana

- Custer County, Idaho

- Sacagawea River in Montana

- Sacajawea State Park in Pasco, Washington

Sculpture

- Astoria, Oregon — Sacagawea and Baby by Jim Demetro: a life-size bronze statue of Sacagawea and Jean-Baptiste, located at the Clatsop National Memorial, Netul Landing in Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, outside the visitor center.[22]

- Bismarck, North Dakota — by Leonard Crunelle (1910): depicted with baby Pomp, located on the grounds of the North Dakota State Capitol. In 2003, a replica was given to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center.[55]

- Boise, Idaho: installed in front of the Idaho History Museum in July 2003.

- Charlottesville, Virginia — Their First View of the Pacific by Charles Keck (1919): a statue of Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and Sacagawea. The Charlottesville City Council voted in November 2019 to remove the statue from its current location, a decision "cheered by the local Native American tribe, the Monacan Indian Nation, and descendants of Sacagawea’s family in Idaho. They say the statue presents a weak and servile image of Sacagawea, who actually was an essential guide and interpreter for Lewis and Clark."[56]

- Cheney, Washington — by Harold Balazs (1960): a statue of Sacagawea is displayed in the rose garden in front of the President's House at Eastern Washington University.

- Cody, Wyoming — by Harry Jackson (1980): painted bronze, 114 inches, the statue is located in the Greever Cashman Garden at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center

- Cody, Wyoming — by Richard V. Greeves (2005): Bronze, 72 inches, the sculpture is in the Robbie Powwow Garden at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

- Fort Benton, Montana — by Robert Scriver: a sculpture of Sacagawea and her baby, and Captains Lewis and Clark, in the riverside sculpture park.

- Fort Worth, Texas — by Glenna Goodacre (2001): Sacajawea statue outside the National Cowgirl Hall of Fame.

- Godfrey, Illinois — by Glenna Goodacre: at Lewis and Clark Community College; by the same artist who designed the image on the Sacagawea dollar

- Great Falls, Montana — by Robert Scriver: bronze 3/4 scale statue of Sacagawea, her baby Jean-Baptise, Lewis, Clark, and the Newfoundland dog Seaman, at the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center.

- Kansas City, Missouri — Corps of Discovery Monument by Eugene L. Daub (2000): includes life-size figures of Sacagawea and Jean-Baptiste, York, and Seaman on the bluff at Clark's Point overlook (Case Park, Quality Hill)[22][57]

- Lander, Wyoming: in local cemetery, 14 miles West on U.S. 287, and then 2 miles West (after a turn); turnoff about three miles South of Fort Washakie; there is a tall statue of Sacagawea (6 ft) with tombstones downhill of her, husband, and two children; there also is a monument on site.

- Lewiston, Idaho: multiple statues, including one along the main approach to the city.

- Longview, Washington, a statue of Sacagawea and Jean-Baptiste was placed in Lake Sacajawea Park near the Hemlock St. footbridge in 2005.

- Mobridge, South Dakota — The Sacagawea Monument: an obelisk erected at the supposed site of her death, which honors Sacagawea as a member of the Shoshone tribe and for her contribution to the Corps of Discovery expedition; the associated marker "dates her death as December 20, 1812 and states that her body must be buried somewhere near the site of old Fort Manuel located 30 miles north of the marker."[22]

- Portland, Oregon — by Alice Cooper (1905): Sacajawea and Jean-Baptiste was unveiled July 6, 1905 and moved to Washington Park, April 6, 1906.[58]

- Portland, Oregon — by Glenna Goodacre: located at Lewis & Clark College, permanently installed on September 5, 2004/[59]

- Richland, Washington — by Tom McClelland (2008)[60]

- St. Louis, Missouri — by Harry Weber (2002): a statue of Sacagawea with her baby in a cradle board is included in the diorama of the Lewis & Clark expedition that is on display in the lobby of the St. Louis Drury Plaza Hotel, located in the historical International Fur Exchange building.[61]

- Three Forks, Montana, in Sacajawea Park — Coming Home by Mary Michael: statue honoring Sacagawea, built in the area where she was abducted as a young girl and taken to Mandan lands.[22]

- Wind River Indian Reservation, Wyoming: According to oral tradition, Sacagawea left her husband Toussaint Charbonneau and fled to Wyoming in the 1860s; her alleged burial site is located in the reservation's cemetery, with a gravestone inscription dating her death as April 9, 1884, however, oral tradition also indicates a woman named Porivo (recorded as "Bazil's mother") occupies that grave.[22]

See also

Notes

- Journal entries by Clark, Lewis, et al., are brief segments of "our nation's 'living history' legacy of documented exploration across our fledgling republic's pristine western frontier. It is a story written in inspired spelling and with an urgent sense of purpose by ordinary people who accomplished extraordinary deeds."[8]

- William Clark created the nickname "Janey" for Sacagawea, which he transcribed twice, November 24, 1805, in his journal, and in a letter to Toussaint, August 20, 1806. It is thought that Clark's use of "Janey" derived from "jane," colloquial army slang for "girl."[8]

References

- "Hall of Great Westerners". National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- "Sacagawea." National Cowgirl Hall of Fame. 2017.

- "Sacagawea / Sacajawea / Sakakawea | Women of the Hall." National Women's Hall of Fame. 2003. Seneca Falls, NY.

- Fresonke, Kris, and Mark David Spence (2004). Lewis & Clark: Legacies, Memories, and New Perspectives. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23822-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Buckley, Jay H. "Sacagawea." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2020.

- Anderson, Irving W. 1999. "Sacagawea | Inside the Corps" (film website). Lewis & Clark. DC: PBS.org.

- Clark, William. [1804] 2004. "November 4, 1804." The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Online, edited by G. E. Moulton, et al. Lincoln, NE: Center for Digital Research in the Humanities and University of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Anderson, Irving W. (Fall 1999). "The Sacagawea Mystique: Her Age, Name, Role and Final Destiny". Columbia Magazine. 13 (3). Archived from the original on February 11, 2008 – via washingtonhistory.org.

- Lewis, Meriwether. [1805] 2004. "August 17, 1805." The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Online, edited by G. E. Moulton, et al. Lincoln, NE: Center for Digital Research in the Humanities and University of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Clark, William. [1805] 2004. "August 17, 1805." The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Online, edited by G. E. Moulton, et al. Lincoln, NE: Center for Digital Research in the Humanities and University of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Clark, William. [1805] 2004. "November 20, 1805." The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Online, edited by G. E. Moulton, et al. Lincoln, NE: Center for Digital Research in the Humanities and University of Nebraska Press. Archived from the original 2 February 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Hebard, Grace Raymond (2012) [1933]. Sacajawea: Guide and Interpreter of Lewis and Clark. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486146362.

- Clark, William. [1805] 2004. "October 13, 1805." The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Online, edited by G. E. Moulton, et al. Lincoln, NE: Center for Digital Research in the Humanities and University of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Clark, William. [1805] 2004. "October 19, 1805." The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Online, edited by G. E. Moulton, et al. Lincoln, NE: Center for Digital Research in the Humanities and University of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Kastor, Peter J., ed. 2003. "Sacagawea in primary sources." American Indian Women. St. Louis: American Cultural Studies, Washington University. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Jackson, Donald, ed. 1962. Letters of the Lewis & Clark Expedition With Related Documents: 1783-1854. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Butterfield, Bonnie (2010). "Sacagawea's Death". Native Americans: The True Story of Sacagawea and Her People. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Original Adoption Documents." St. Louis, Missouri: Orphans Court Records. 11 August 1813.

- Butterfield, Bonnie (November 28, 2011). "Sacagawea and Her Shoshone People". Native Americans: The True Story of Sacagawea and Her People. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Drumm, Stella M., ed. 1920. Journal of a Fur-trading Expedition on the Upper Missouri: John Luttig, 1812–1813. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society.

- Worley, Ramona Cameron. 2011. Sacajawea 1788–1884: Examine the Evidence. Lander, WY. p. 17.

- "Historical Landmarks". Sacagawea-Biography.org.

- Wilson, Raymond (1999). Ohiyesa: Charles Eastman, Santee Sioux. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06851-5.

- Clark, Ella E. & Edmonds, Margot (1983). Sacagawea of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05060-0.

- Klein, Christopher (2018) [2012]. "Who's Buried in Sacagawea's Grave?". History Channel. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "Wyoming History Day Student Resources Skill-Building for Letter Writing". American Heritage Center. Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming. Instructions. Archived from the original on 2012-02-13. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "Lewis and Clark Trail". Lewis and Clark Trail. 2001-01-17. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- Mickelson, Sandy. "Sacajawea legend may not be correct." The Messenger. Fort Dodge, IA. Mickelson recounts the findings from Thomas H. Johnson, who argues in his "Also Called Sacajawea: Chief Woman's Stolen Identity" that Hebard had the wrong woman when she relied upon oral history that an old woman who died and is buried on the Wyoming Wind River Reservation was Sacajawea, the Shoshone woman who participated in the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

- Scharff, Virginia. 1989. "The Independent and Feminine Life: Grace Raymond Hebard, 1861–1936." Pp. 127–45 in Lone Voyagers: Academic Women in Coeducational Universities, 1870–1937, edited by G. J. Clifford. New York: Feminist Press. ISBN 9780935312850.

- Park, Indrek. 2012. Grammar of Hidatsa (Ph.D. dissertation). Bloomington: Indiana University. p. 36.

- "Reading Lewis and Clark – Thomasma, Clark, and Edmonds" Archived 2006-09-26 at the Wayback Machine, Idaho Commission for Libraries

- Koontz, John (ed.). "Etymology". Siouan Languages. Retrieved 2007-04-01 – via spot.colorado.edu.

- Bright, William (2004). Native American Place Names in the United States. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 413.

- Hartley, Alan H. (2002). "[Unknown]". Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas Newsletter. 20 (4): 12–13.

- Reid, Russell (1986). Sakakawea: The Bird Woman. Bismarck, South Dakota: State Historical Society of North Dakota. Archived from the original on 2008-05-14. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- Matthews, Washington, ed. (1877). Ethnography and Philology of the Hidatsa Indians. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Rees, John E. [c. 1920s] 1970. "Madame Charbonneau" (excerpt). The Lemhi County Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "[The Lewis and Clark Expedition] merited less than a single paragraph in John Clark Ridpath's 691-page Popular History of the United States of America (1878).… Within three years of publication of Dye's novel the first book devoted exclusively to Sacagawea, Katherine Chandler's The Bird-Woman of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, appeared as a supplementary reader for elementary school students." [Chandler's book used the "Sacajawea" spelling.] Dippie, Brian W. "Sacagawea Imagery", Chief Washakie Foundation

- George, Rozina. "Agaidika Perspective on Sacajawea", Life Long Learning: The Lewis and Clark Rediscovery Project.

- "Sacajawea (Character)". IMDb.

- ""The Girl Who Walked the West" on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Data Base. November 4, 1967. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- Dye, Eva Emery (1902). .

- "Schoolhouse Rock 'Elbow Room'". Retrieved 2012-02-13 – via Youtube.com.

- "Tingstad & Rumbel discography". tingstadrumbel.com.

- Craig, Pat. 30 December 2007. "Tale of Sacagawea to premiere in July". East Bay Times.

- Goldman, Justin. 28 May 2008. "Summer Hot List". Diablo Magazine.

- Craig, Pat. 3 August 2008. "Willows Theatre presents Sacagawea, another theatrical chapter in Western history." East Bay Times.

- "Willows Theatre Company Announces Summer Festival". BroadwayWorld. 20 May 2008.

- "Alessandra Celetti: "Sketches of Sacagawea" (2010, Al-Kemi Lab)". distorsioni-it.blogspot.it. April 1, 2011.

- "Sacajawea | Place Settings." The Dinner Party. New York: Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 29 May 2020. See also: Overview of the concept by Kay Keys 2007. Retrieved on 2015-08-06.

- "Episode 1: Sacajawea". The Broadsides – via itunes.apple.com.

- "Sergeant Sacagawea". lewisandclarktrail.com. 2009-01-04. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- "TERMS OF USE (06/11)". USMint.gov. United States Mint, Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Department of Treasury. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- "Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Educational Center". sacajaweacenter.org. Salmon, IA: Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural & Educational Center. Archived from the original on 2012-02-18. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- Biography and Photo of the Statue of Sacagawea, at the National Statuary Hall in Washington, DC

- Heim, Joe (November 29, 2019). "Charlottesville votes to remove another statue, and more controversy follows". Washington Post.

- "Clark's Point, Case Park". LewisandClarkTrail.com. 2008-06-29. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- "Sacajawea and Jean-Baptiste", sculpted by Alice Cooper

- "Sculpture of Sacagawea and Jean Baptiste". lclark.edu. Lewis & Clark College. 2004-09-05. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- "City of Richland Public Art Catalog". City of Richland. p. 19. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- Weber, Harry. "'Late May 1805' diorama". nps.gov. US National Park Service.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sacagawea. |

- "Profile: Sacagawea", National Park Service

- Museum of Human Beings, a book by Colin Sargent

- Sacagawea – A Pioneer Interpreter at teck-translations.com

- Lewis and Clark Expedition Maps and Receipt. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.