Foreign and Commonwealth Office

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), commonly called the Foreign Office (which was the formal name of its predecessor until 1968), or British Foreign Office, is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom. In September 2020, the FCO will be merged to create the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO)[2] and the Foreign Secretary's responsibilities will merge with that of the Secretary of State for International Development. It is responsible for protecting and promoting British interests worldwide and was created in 1968 by merging the Foreign Office and the Commonwealth Office.

| |

Foreign and Commonwealth Office Main Building, London, seen from Whitehall | |

| Department overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1968 |

| Preceding agencies |

|

| Jurisdiction | United Kingdom |

| Headquarters | King Charles Street London, SW1 51°30′11″N 0°07′40″W |

| Annual budget | £1.1bn (current) & £0.1bn (capital) in 2015–16[1] |

| Ministers responsible |

|

| Department executive |

|

| Child agencies |

|

| Website | www |

The head of the FCO is the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, commonly abbreviated to "Foreign Secretary". This is regarded as one of the four most prestigious positions in the Cabinet – the Great Offices of State – alongside those of Prime Minister, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Home Secretary.

The FCO is managed from day to day by a civil servant, the Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, who also acts as the Head of Her Majesty's Diplomatic Service. This position is held by Sir Simon McDonald, who took office on 1 September 2015.

On the 16 June, 2020 it was announced the FCO will be merged with the Department for International Development, and will be dissolved by September of the same year. The resulting department will be named the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, and will take a new form[3].

Responsibilities

According to the FCO website, the department's key responsibilities (as of 2020) are as follows:[4]

- Safeguarding the UK's national security by countering terrorism and weapons proliferation, and working to reduce conflict.

- Building the UK's prosperity by increasing exports and investment, opening markets, ensuring access to resources, and promoting sustainable global growth.

- Supporting British nationals around the world through modern and efficient consular services.

Ministers

The FCO Ministers are as follows:[5][6]

| Minister | Rank | Portfolio |

|---|---|---|

| The Rt Hon. Dominic Raab MP | Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs | Overall responsibility for the department; Strategy Directorate; national security; intelligence; honours; Europe. |

| The Rt Hon. James Cleverly MP | Minister of State for Middle East & North Africa | Middle East and North Africa; conflict, humanitarian issues, human security; CHASE (Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department); Stabilisation Unit; defence and international security; Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OCSE) and Council of Europe; Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF); safeguarding. |

| The Rt Hon. The Lord Goldsmith of Richmond Park PC | Minister of State for the Pacific, Environment and Conservation (Jointly with DEFRA) | climate change, environment and conservation, biodiversity; oceans; Oceania; Blue Belt. |

| Nigel Adams MP | Minister of State for Asia | East Asia and South East Asia; economic diplomacy; trade; Economics Unit; Prosperity Fund; soft power, including British Council, BBC World Service and scholarships; third-country agreements; consular. |

| The Rt Hon. The Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon | Minister of State for South Asia and the Commonwealth | South Asia; Commonwealth; UN and multilateral; governance and democracy; open societies and anti-corruption; human rights, including Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI); treaty policy and practice; sanctions; departmental operations: human resources and estates. |

| James Duddridge MP | Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Africa | Sub-Saharan Africa; economic development; international financial institutions; CDC (UK government’s development finance institution). |

| Wendy Morton MP | Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for the European Neighbourhood and the Americas | East and South-East Europe; Central Asia; Americas; health, global health security, neglected tropical diseases; water and sanitation; nutrition; Global Fund, GAVI (the Vaccine Alliance). |

| The Rt Hon. The Baroness Sugg | Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for the Overseas Territories and Sustainable Development | Overseas Territories; children, education and youth (including girls’ education); sexual and reproductive health and rights, women and girls, LGBT, civil society, inclusive societies, disability; global partnerships and Sustainable Development Goals; departmental operations: finance and protocol |

History

Eighteenth century

The Foreign Office was formed in March 1782 by combining the Southern and Northern Departments of the Secretary of State, each of which covered both foreign and domestic affairs in their parts of the Kingdom. The two departments' foreign affairs responsibilities became the Foreign Office, whilst their domestic affairs responsibilities were assigned to the Home Office. The Home Office is technically the senior.[7]

Nineteenth century

During the 19th century, it was not infrequent for the Foreign Office to approach The Times newspaper and ask for continental intelligence, which was often superior to that conveyed by official sources.[8] Examples of journalists who specialized in foreign affairs and were well connected to politicians included: Henry Southern, Valentine Chirol, Harold Nicolson, and Robert Bruce Lockhart.[9]

Twentieth century

During the First World War, the Arab Bureau was set up within the British Foreign Office as a section of the Cairo Intelligence Department. During the early cold war an important department was the Information Research Department, set up to counter Soviet propaganda and infiltration. The Foreign Office hired its first woman diplomat, Monica Milne, in 1946.[10]

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office (1968-2020)

The FCO was formed on 17 October 1968, from the merger of the short-lived Commonwealth Office and the Foreign Office.[11] The Commonwealth Office had been created only in 1966, by the merger of the Commonwealth Relations Office and the Colonial Office, the Commonwealth Relations Office having been formed by the merger of the Dominions Office and the India Office in 1947—with the Dominions Office having been split from the Colonial Office in 1925.

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office held responsibility for international development issues between 1970 and 1974, and again between 1979 and 1997.

The National Archives website contains a Government timeline to show the departments responsible for Foreign Affairs from 1945.[12]

Under New Labour (1997-2010)

From 1997, international development became the responsibility of the separate Department for International Development.

When David Miliband took over as Foreign Secretary in June 2007, he set in hand a review of the FCO's strategic priorities. One of the key messages of these discussions was the conclusion that the existing framework of ten international strategic priorities, dating from 2003, was no longer appropriate. Although the framework had been useful in helping the FCO plan its work and allocate its resources, there was agreement that it needed a new framework to drive its work forward.

The new strategic framework consists of three core elements:

- A flexible global network of staff and offices, serving the whole of the UK Government.

- Three essential services that support the British economy, British nationals abroad and managed migration for Britain. These services are delivered through UK Trade & Investment (UKTI), consular teams in Britain and overseas, and UK Visas and Immigration.

- Four policy goals:

- countering terrorism and weapons proliferation and their causes

- preventing and resolving conflict

- promoting a low-carbon, high-growth, global economy

- developing effective international institutions, in particular the United Nations and the European Union.

In August 2005, a report by management consultant group Collinson Grant was made public by Andrew Mackinlay. The report severely criticised the FCO's management structure, noting:

- The Foreign Office could be "slow to act".

- Delegation is lacking within the management structure.

- Accountability was poor.

- The FCO could feasibly cut 1200 jobs.

- At least £48 million could be saved annually.

The Foreign Office commissioned the report to highlight areas which would help it achieve its pledge to reduce spending by £87 million over three years. In response to the report being made public, the Foreign Office stated it had already implemented the report's recommendations.[13]

In 2009, Gordon Brown created the position of Chief Scientific Adviser (CSA) to the FCO. The first science adviser was David C. Clary.[14]

On 25 April 2010, the department apologised after The Sunday Telegraph obtained a "foolish" document calling for the upcoming September visit of Pope Benedict XVI to be marked by the launch of "Benedict-branded" condoms, the opening of an abortion clinic and the blessing of a same-sex marriage.[15]

Coalition and Conservatives (2010-20)

.jpg)

In 2012, the Foreign Office was criticised by Gerald Steinberg, of the Jerusalem-based research institute NGO Monitor, saying that the Foreign Office and the Department for International Development provided more than £500,000 in funding to Palestinian NGOs which he said "promote political attacks on Israel." In response, a spokesman for the Foreign Office said "we are very careful about who and what we fund. The objective of our funding is to support efforts to achieve a two-state solution. Funding a particular project for a limited period of time does not mean that we endorse every single action or public comment made by an NGO or by its employees."[16]

In September 2012, the FCO and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs signed a Memorandum of Understanding on diplomatic cooperation, which promotes the co-location of embassies, the joint provision of consular services, and common crisis response. The project has been criticised for further diminishing the UK's influence in Europe.[17]

In 2011, the then Foreign Secretary, William Hague, announced the government's intention to a number of new diplomatic posts in order to enhance the UK's overseas network.[18] [19] As such, eight new embassies and six new consulates were opened around the world.[20]

Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (2020-present)

On 16 June 2020, Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced the merger of the FCO with the Department for International Development.[21] This was following the decision in the February 2020 cabinet reshuffle to give cross-departmental briefs to all junior ministers in Department for International Development and the Foreign Office.[22] The merger, which will create the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, is expected to take place in September 2020[23] with a stated aim of ensuring that aid is spent "in line with the UK's priorities overseas."[24] The merger was criticized by three former Prime Ministers - Gordon Brown, Tony Blair and David Cameron, with Cameron saying it would mean "less respect for the UK overseas".[25] The Chief Executive of Save the Children, Kevin Watkins, called it a "reckless, irresponsible and a dereliction of UK leadership" that "threatens to reverse hard-won gains in child survival, nutrition and poverty". [25]

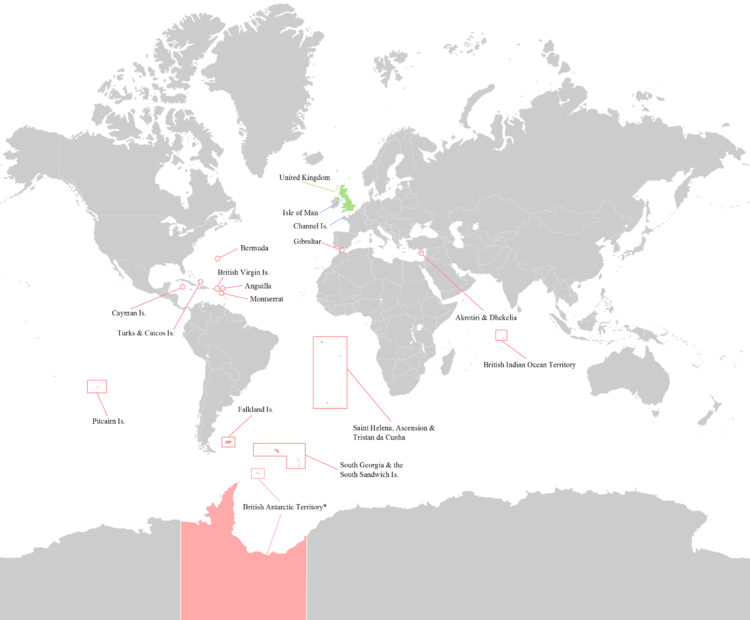

Overseas Territories Directorate

The Overseas Territories Directorate is responsible for the British Overseas Territories.[26] Meanwhile, responsibly for the Sovereign Base Areas in Akrotiri and Dhekelia lies with the Ministry of Defence.[27] The FCO inherited responsibility for the overseas territories in 1968 (previously handled by the Colonial Office and latterly the short-lived Commonwealth Office.[28] The relationship between the UK government and the overseas territories has changed considerably since then, with the territories originally being referred to as colonies, then dependent territories and finally, in 2002, becoming overseas territories.[29] As part of this enhanced status, a special 'British Overseas Territories Citizenship' was created with was given equal status alongside British Citizenship.

Despite these efforts at modernization, however, critics both in the UK and in the overseas territories have pointed to the lack of focus on and support for the overseas territories with the relationship between them and the UK needing an overhaul.[30] The Chief Minister of Anguilla, Victor Banks, said: “We are not foreign; neither are we members of the Commonwealth, so we should have a different interface with the UK that is based on mutual respect”.[31]

There have been numerous suggestions on ways to improve the relationship between the overseas territories and the UK. Suggestions have included setting up a dedicated department to handle relations with the overseas territories and the absorption of the OTD in the Cabinet Office, thus affording the overseas territories with better connections to the centre of government.[32]

Diplomatic Academy

Following a prior announcement by the then Foreign Secretary William Hague, the FCO opened the Diplomatic Academy in February 2015.[33] The new centre, opened by the Duke of Cambridge, was established in order to create a cross-government centre of excellence for all civil servants working on international issues.[34] The Diplomatic Academy serves to broaden the FCO's network and engaged in more collaborative work with academic and diplomatic partners.[35]

Programme Funds

The FCO, through its core departmental budget, funds projects which are in line with its policy priorities outlined in its Single Departmental Plan.[36] This funding includes both Official Development Assistance (ODA), and non-ODA funds. The funds are used for a wide range of projects and serve to support traditional diplomatic activities.[37]

The FCO plays a key role in delivering two, major UK government funds which work to support the government's National Security Strategy and Aid Strategy.[38]

- The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) - Used to support cross-governmental efforts at reducing conflict-related risks in countries which the UK has important interests.[39]

- The Prosperity Fund - Supports economic development and reform in the UK's partner countries.[40]

The FCO also supports a number of academic funds:

FCO Services

In April 2006, a new executive agency was established, FCO Services, to provide corporate service functions.[46] It moved to Trading Fund status in April 2008, so that it had the ability to provide services similar to those it already offers to the FCO[47] to other government departments and even to outside businesses.

It is accountable to the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, and provides secure support services to the FCO, other government departments and foreign governments and bodies with which the UK has close links.[48]

Since 2011, FCO Services has been developing the Government Secure Application Environment (GSAE) on a secure cloud computing platform to support UK government organisations.[49] it also manages the UK National Authority for Counter Eavesdropping (UK NACE) which helps protect UK assets from physical, electronic and cyber attack.[50]

For over 10 years, FCO Services has been working globally, to keep customer assets and information safe. FCO Services is a public sector organisation, it is not funded by the public and has to rely on the income it produces to meet its costs, by providing services on a commercial basis to customers both in the UK and throughout the world. Its Accounting Officer and Chief Executive is accountable to the Secretary of State for Foreign & Commonwealth Affairs and to Parliament, for the organisation's performance and conduct.

Buildings

As well as embassies abroad, the FCO has premises within the UK:

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office Main Building, Whitehall, King Charles St, London (abbreviated to KCS by FCO staff)

- Hanslope Park, Hanslope, Milton Keynes (abbreviated to HSP by FCO staff). Location of FCO Services, HMGCC and Technical Security Department of the UK Secret Intelligence Service)

- Lancaster House, St James's, London. A mansion in the St James's district in the West End of London which the Foreign Office holds on lease from the Crown. It is used primarily for hospitality, entertaining foreign dignitaries and housing the Government Wine Cellar.

The FCO formerly also used the following building:

- Old Admiralty Building, Whitehall, London (abbreviated to OAB by FCO staff)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office Main Building

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office occupies a building which originally provided premises for four separate government departments: the Foreign Office, the India Office, the Colonial Office, and the Home Office. Construction on the building began in 1861 and finished in 1868, on the plot of land bounded by Whitehall, King Charles Street, Horse Guards Road and Downing Street. The building was designed by the architect George Gilbert Scott.[51] Its architecture is in the Italianate style; Scott had initially envisaged a Gothic design, but Lord Palmerston, then Prime Minister, insisted on a classical style.[51] The English sculptors Henry Hugh Armstead and John Birnie Philip produced a number of allegorical figures ("Art", "Law", "Commerce", etc.) for the exterior.

In 1925 the Foreign Office played host to the signing of the Locarno Treaties, aimed at reducing tension in Europe. The ceremony took place in a suite of rooms that had been designed for banqueting, which subsequently became known as the Locarno Suite.[52] During the Second World War, the Locarno Suite's fine furnishings were removed or covered up, and it became home to a Foreign Office code-breaking department.[52]

Due to increasing numbers of staff, the offices became increasingly cramped and much of the fine Victorian interior was covered over—especially after the Second World War. In the 1960s, demolition was proposed, as part of major redevelopment plan for the area drawn up by the architect Sir Leslie Martin.[51] A subsequent public outcry prevented these proposals from ever being implemented. Instead, the Foreign Office became a Grade I listed building in 1970.[51] In 1978, the Home Office moved to a new building, easing overcrowding.

With a new sense of the building's historical value, it underwent a 17-year, £100 million restoration process, completed in 1997.[51] The Locarno Suite, used as offices and storage since the Second World War, was fully restored for use in international conferences. The building is now open to the public each year over Open House Weekend.

In 2014 refurbishment to accommodate all Foreign and Commonwealth Office employees into one building was started by Mace.[53]

The FCO Main Building

The FCO Main Building The Grand Staircase

The Grand Staircase The Grand Locarno Room

The Grand Locarno Room The Durbar Court at the former India Office, now part of the FCO

The Durbar Court at the former India Office, now part of the FCO The Muse Staircase

The Muse Staircase

Devolution

International relations are handled centrally from Whitehall on behalf of the whole of the United Kingdom and its dependencies. However, the devolved administrations also maintain an overseas presence in the European Union, the USA and China alongside British diplomatic missions. These offices aim to promote their own economies and ensure that devolved interests are taken into account in British foreign policy. Ministers from devolved administrations can attend international negotiations when agreed with the British Government e.g. EU fisheries negotiations.[54] Similarly, ministers from the devolved administrations meet at approximately quarterly intervals through the Joint Ministerial Committee (Europe), chaired by the Foreign Secretary to "discuss matters bearing on devolved responsibilities that are under discussion within the European Union."

See also

- Conflict, Stability and Security Fund

- Department for International Development

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office migrated archives

- National Security Adviser (United Kingdom)

- National Security Council (United Kingdom)

- Palmerston (cat), resident Chief Mouser of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office

- Stabilisation Unit

References

- Foreign Office Settlement. London: HM Treasury. 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- https://www.civilservicejobs.service.gov.uk/csr/index.cgi?SID=cGFnZWFjdGlvbj12aWV3dmFjYnlqb2JsaXN0JnVzZXJzZWFyY2hjb250ZXh0PTEwMzg3OTI0MSZzZWFyY2hfc2xpY2VfY3VycmVudD0xJmNzb3VyY2U9Y3Nxc2VhcmNoJm93bmVyPTUwNzAwMDAmcGFnZWNsYXNzPUpvYnMmam9ibGlzdF92aWV3X3ZhYz0xNjc5OTk0Jm93bmVydHlwZT1mYWlyJnJlcXNpZz0xNTk0OTg2Mjg2LWQ5Mzc3Mjc0NmE1NGYyZTJmZjRiOTcyNzcxZDAxNzQ2MDU2Zjk4ZmI=

- https://www.itv.com/news/2020-06-16/department-for-international-development-dfid-to-merge-with-foreign-office/

- https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/foreign-commonwealth-office/about

- "Our ministers". GOV.UK. Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- "Her Majesty's Official Opposition". UK Parliament. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- A brief history of the FCO Foreign and Commonwealth Office

- Weller, Toni (June 2010). "The Victorian information age: nineteenth century answers to today's information policy questions?". History & Policy. United Kingdom: History & Policy. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- Berridge, G. R. "A Diplomatic Whistleblower in the Victorian Era" (PDF). grberridge.diplomacy.edu. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- "Women and the Foreign Office". Issu.com. Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "The Foreign and Commonwealth Ministries merge". The Glasgow Herald. 17 October 1968. p. 1. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Archives, The National. "The National Archives – Homepage". labs.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- "BBC NEWS – UK – UK Politics – Foreign Office management damned".

- Clary, David (16 September 2013). "A Scientist in the Foreign Office". Science & Diplomacy. 2 (3).

- "Apology over Pope 'condom' memo". BBC News. 25 April 2010.

- "'Investigate UK funding of Palestinian NGOs'". thejc.com.

- Gaspers, Jan (November 2012). "At the Helm of a New Commonwealth Diplomatic Network: In the United Kingdom's Interest?". Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=Q5PGCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT52&lpg=PT52&dq=william+hague+fco+new+embassies&source=bl&ots=BMk12F4WNQ&sig=ACfU3U1TIdDqlOFjZKIM5oRRSDHUVZca1Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi-3LqIoZ7qAhWCOnAKHe_wDCEQ6AEwBXoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=william%20hague%20fco%20new%20embassies&f=false

- https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/looking-after-our-own-strengthening-britains-consular-diplomacy--2

- https://www.conservativehome.com/platform/2012/04/william-hague.html

- "International development and Foreign Office to merge". BBC News. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Joint ministerial team at Foreign Office and DfID reignites merger rumours". Civil Service World. 17 February 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Foreign Office and International Development merger will curb 'giant cashpoint' of UK aid, PM pledges". Sky News. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Prime Minister announces merger of Department for International Development and Foreign Office". GOV.UK. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Stewart, Heather; Wintour, Patrick (16 June 2020). "Three ex-PMs attack plan to merge DfID with Foreign Office". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Foreign & Commonwealth Office (June 2012). The Overseas Territories: Security, Success and Sustainability (PDF). ISBN 9780101837422.

- British Overseas Territories Law, Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson, Hart Publishing, Oxford, 2011, p. 340

- https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmfaff/1464/146405.htm

- https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmfaff/1464/146405.htm

- https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmfaff/1464/146405.htm

- http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/foreign-affairs-committee/the-future-of-the-uk-overseas-territories/oral/93391.html

- Global Britain and the British Overseas Territories: Resetting the relationship

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/opening-of-new-diplomatic-academy

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/opening-of-new-diplomatic-academy

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/opening-of-new-diplomatic-academy

- https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/foreign-commonwealth-office/about

- https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/foreign-commonwealth-office/about

- https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/foreign-commonwealth-office/about

- https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/conflict-stability-and-security-fund/about

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cross-government-prosperity-fund-programme

- https://www.chevening.org/

- https://www.marshallscholarship.org/

- https://www.gov.uk/guidance/forced-marriage#domestic-programme-fund

- https://www.gov.uk/guidance/darwin-plus-applying-for-projects-in-uk-overseas-territories

- https://www.gov.uk/world/organisations/uk-science-and-innovation-network

- "Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs". Hansard. March 2006.

- "The FCO Services Trading Fund Order 2008". UK Legislation. National Archives. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- "Who we are". FCO Services. 24 May 2011. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2011.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Say, Mark (21 July 2011). "FCO Services pushes secure cloud platform". Guardian Government Computing. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- https://www.fcoservices.gov.uk/our-organisation/

- Foreign & Commonwealth Office History Archived 24 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Foreign & Commonwealth Office: Route" (PDF). FCO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2012.

- "Mace wins £20m Whitehall Foreign Office refit". constructionenquirer.com.

- Scottish gains at Euro fish talks, Scottish Government, 16 December 2009

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Foreign Office. |

- Official website

- Cockerell, Michael (1998). How to Be Foreign Secretary (Television production). BBC.

- Cockerell, Michael (2010). The Great Offices of State: Palace of Dreams (Television production). BBC.

.svg.png)