Supreme Court of the United Kingdom

The Supreme Court (initialism: UKSC or the acronym: SCOTUK) is the final court of appeal in the United Kingdom for civil cases, and for criminal cases from England, Wales and Northern Ireland. It hears cases of the greatest public or constitutional importance affecting the whole population, including disputes relating to devolution.[2]

| Supreme Court of the United Kingdom | |

|---|---|

| Cornish: An Lys Gorughel Irish: An Chúirt Uachtarach Scots: The Supreme Coort Scottish Gaelic: An Àrd Chùirt Welsh: Y Goruchaf Lys | |

.svg.png) | |

| Established | 1 October 2009 |

| Jurisdiction | United Kingdom (civil cases) England and Wales and Northern Ireland (criminal cases) |

| Location | Middlesex Guildhall, Parliament Square, London, England |

| Coordinates | 51°30′01″N 0°07′41″W |

| Composition method | Appointed by the Monarch (Queen-on-the-Bench) on the advice of the Prime Minister, following approval of a recommendation by the Secretary of State for Justice |

| Authorized by | Constitutional Reform Act 2005, Part 3, Section 23(1) and s. 23 (whole section)[1] |

| Appeals from |

|

| Number of positions | 12 |

| Website | www |

| President | |

| Currently | Lord Reed |

| Since | 13 January 2020 |

| Deputy President | |

| Currently | Lord Hodge |

| Since | 27 January 2020 |

As authorised by the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, Part 3, Section 23(1),[1] the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom was formally established on 1 October 2009 and is a non-ministerial government department of the Government of the United Kingdom,[3].

It assumed the judicial functions of the House of Lords, which had been exercised by the Lords of Appeal in Ordinary (commonly called "Law Lords"), the 12 judges appointed as members of the House of Lords to carry out its judicial business as the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords. Its jurisdiction over devolution matters had previously been exercised by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

The current President of the Supreme Court is Lord Reed.

Introduction

The United Kingdom has a doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty, so the Supreme Court is much more limited in its powers of judicial review than the constitutional or supreme courts of some other countries. It cannot overturn any primary legislation made by Parliament. However, it can overturn secondary legislation if, for an example, that legislation is found to be ultra vires to the powers in primary legislation allowing it to be made.

Further, under section 4 of the Human Rights Act 1998, the Supreme Court, like some other courts in the United Kingdom, may make a declaration of incompatibility, indicating that it believes that the legislation subject to the declaration is incompatible with one of the rights in the European Convention on Human Rights. Such a declaration can apply to primary or secondary legislation. The legislation is not overturned by the declaration, and neither Parliament nor the government is required to agree with any such declaration. However, if they do accept a declaration, ministers can exercise powers under section 10 of the Human Rights Act to amend the legislation by statutory instrument to remove the incompatibility or ask Parliament to amend the legislation.

History

Creation

.jpg)

The creation of a Supreme Court for the United Kingdom was first mooted in a consultation paper published by the Department of Constitutional Affairs in July 2003.[4] Although the paper noted that there had been no criticism of the then-current Law Lords or any indication of an actual bias, it argued that the separation of the judicial functions of the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords from the legislative functions of the House of Lords should be made explicit. The paper noted the following concerns:

- Whether there was any longer sufficient transparency of independence from the executive and the legislature to give assurance of the independence of the judiciary.[4]

- The requirement for the appearance of impartiality and independence limited the ability of the Law Lords to contribute to the work of the House itself, thus reducing the value to both them and the House of their membership.[4]

- It was not always understood by the public that judicial decisions of "the House of Lords" were in fact taken by the Appellate Committee and that non-judicial members were never involved in the judgments. Conversely, it was felt that the extent to which the Law Lords themselves had decided to refrain from getting involved in political issues in relation to legislation on which they might later have had to adjudicate was not always appreciated.[4] The new President of the Court, Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers, has claimed that the old system had confused people and that with the Supreme Court there would for the first time be a clear separation of powers among the judiciary, the legislature and the executive.[5]

- Space within the House of Lords was at a constant premium and a separate supreme court would ease the pressure on the Palace of Westminster.[4]

The main argument against a new Supreme Court was that the previous system had worked well and kept costs down.[6] Reformers expressed concern that this second main example of a mixture of the legislative, judicial and executive might conflict with professed values under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Officials who make or execute laws have an interest in court cases that put those laws to the test. When the state invests judicial authority in those officials or even their day-to-day colleagues, it puts the independence and impartiality of the courts at risk. Consequently, it was hypothesised closely connected decisions of the Law Lords to debates had by friends or on which the Lord Chancellor had expressed a view might be challenged on human-rights grounds on the basis that they had not constituted a fair trial.[7]

Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury, later President of the Supreme Court, expressed fear that the new court could make itself more powerful than the House of Lords committee it succeeded, saying that there is a real risk of "judges arrogating to themselves greater power than they have at the moment". Lord Phillips said such an outcome was "a possibility", but was "unlikely".[8]

The reforms were controversial and were brought forward with little consultation but were subsequently extensively debated in Parliament.[9] During 2004, a select committee of the House of Lords scrutinised the arguments for and against setting up a new court.[10] The Government estimated the set-up cost of the Supreme Court at £56.9 million.[11]

Cases and competences

The first case heard by the Supreme Court was HM Treasury v Ahmed, which concerned "the separation of powers", according to Phillips, its inaugural President. At issue was the extent to which Parliament has, by the United Nations Act 1946, delegated to the executive the power to legislate. Resolution of this issue depended upon the approach properly to be adopted by the court in interpreting legislation which may affect fundamental rights at common law or under the European Convention on Human Rights.

Jurisdiction and powers

From the Supreme Court —

The Supreme Court is the final court of appeal in the UK for civil cases, and for criminal cases from England, Wales and Northern Ireland. It hears cases of the greatest public or constitutional importance affecting the whole population.[2]

For Scottish civil cases decided prior to September 2015, permission to appeal from the Court of Session was not required and any such case can proceed to the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom if two advocates certify that an appeal is suitable. The entry into force of the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 has essentially brought the procedure for current and future Scottish civil cases into line with England, Wales and Northern Ireland, where permission to appeal is required, either from the Court of Session or from a Justice of the Supreme Court itself.

The Supreme Court's focus is on cases that raise points of law of general public importance. As with the former Appellate Committee of the House of Lords, appeals from many fields of law are likely to be selected for hearing, including commercial disputes, family matters, judicial review claims against public authorities and issues under the Human Rights Act 1998.

The Supreme Court only exceptionally hears criminal appeals from the High Court of Justiciary with respect to "devolution issues".

The Supreme Court also determines "devolution issues" (as defined by the Scotland Act 1998, the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and the Government of Wales Act 2006). These are legal proceedings about the powers of the three devolved administrations—the Northern Ireland Executive and Northern Ireland Assembly, the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Government and Senedd Cymru. Devolution issues were previously heard by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council and most are about compliance with rights under the European Convention on Human Rights, brought into national law by the Devolution Acts and the Human Rights Act 1998.

Panels and sittings

All twelve justices do not all hear every case. Unless there are circumstances requiring a larger panel, a case is usually heard by a panel of five justices.[12] More than five justices may sit on a panel where the case is of "high constitutional importance" or "great public importance"; if the case raises "an important point in relation to the European Convention on Human Rights"; if the case involves a conflict of decisions among the House of Lords, Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, or Supreme Court; or if the Court "is being asked to depart, or may decide to depart from" its previous precedent.[12]

To avoid a tie, all cases are heard by a panel containing an odd number of justices.[13] Thus, the largest possible panel for a case is 11 justices.[13] To date, there have been only two occasions (both involving matters of major constitutional importance) heard by 11 justices: the case of R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union (argued in 2016 and decided in 2017) and the cases of R (Miller) v The Prime Minister and Cherry v Advocate General for Scotland (argued and decided in 2019).[14][15]

Administration

The Supreme Court has a separate administration from the other courts of the United Kingdom, under a Chief Executive who is appointed by the Court's President.[16][17][18]

Other "supreme courts" in the United Kingdom

The High Court of Justiciary, the Court of Session, and the Office of the Accountant of Court make up the College of Justice, and are known as "the Supreme Courts of Scotland".[19]

Prior to 1 October 2009, there were two other courts known as "the supreme court", namely the Supreme Court of England and Wales (known as "the Supreme Court of Judicature", prior to the passing and coming-into-force of the Senior Courts Act 1981), which was created in the 1870s under the Judicature Acts, and the Supreme Court of Judicature of Northern Ireland, both of which consisted of a Court of Appeal, a High Court of Justice and a Crown Court. When the provisions of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 came into force these became known as the Senior Courts of England and Wales and the Court of Judicature of Northern Ireland respectively.

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council also retains jurisdiction over certain matters. By Section 4 of the Judicial Committee Act, the Sovereign may refer any case whatsoever to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council - effectively allowing the JCPC to take supreme jurisdiction on any case whatsoever when referred by the Sovereign.[20]

The judicial functions of the House of Lords have all been abolished, other than the trial of impeachments, a procedure which has been obsolete for 200 years.

Judges

The court is composed of the President and Deputy President and ten other Justices of the Supreme Court, all with the style of "Justices of the Supreme Court" under section 23(6) of the Constitutional Reform Act.[1] The President and Deputy President of the court are separately appointed to those roles.

The ten Lords of Appeal in Ordinary (Law Lords) holding office on 1 October 2009 became the first judges of the twelve-member Supreme Court.[21] The eleventh place on the Supreme Court was filled by Lord Clarke (formerly the Master of the Rolls), who was the first justice to be appointed directly to the Supreme Court.[22] One of the former Law Lords, Lord Neuberger, was appointed to replace Clarke as Master of the Rolls,[23] and so did not move to the new court. Lord Dyson became the twelfth and final judge of the Supreme Court on 13 April 2010.[24] In 2010, Queen Elizabeth II granted justices who are not peers use of the title Lord or Lady, by warrant under the royal sign-manual.[25][26]

The Senior Law Lord on 1 October 2009, Lord Phillips, became the Supreme Court's first President,[27] and the Second Senior Law Lord, Lord Hope, became the first Deputy President.

On 30 September 2010 Lord Saville became the first justice to retire,[28] followed by Lord Collins on 7 May 2011, although the latter remained as an acting judge until the end of July 2011.

In June 2011 Lord Rodger became the first justice to die in office, after a short illness.[29]

Acting judges

In addition to the twelve permanent judges, the President may request other senior judges drawn from two groups to sit as "acting judges" of the Supreme Court.[30]

- The first group are those judges who hold 'office as a senior territorial judge': judges of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales, judges of the Court of Appeal of Northern Ireland and judges of the First or Second Division of the Inner House of the Court of Session in Scotland.

- The second group are known as the 'supplementary panel'. The President may approve in writing retired senior judges' membership of this panel if they are under 75 years of age (a system similar to senior status in the United States Federal Courts of Appeal).

Appointment process

The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 makes provision for a new appointment process for Justices of the Supreme Court. An independent selection commission is to be formed when vacancies arise. This is to be composed of the President of the Supreme Court (the chair), another senior UK judge (not a Supreme Court Justice), and a member of the Judicial Appointments Commission of England and Wales, the Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland and the Northern Ireland Judicial Appointments Commission. By law, at least one of these cannot be a lawyer. However, there is a similar but separate commission to appoint the next President of the Supreme Court, which is chaired by one of the non-lawyer members and features another Supreme Court Justice in the place of the President. Both of these commissions are convened by the Secretary of State for Justice (Lord Chancellor).[31] In October 2007, the Ministry of Justice announced that the appointment process would be adopted on a voluntary basis for appointments of Lords of Appeal in Ordinary.[32]

The commission selects one person for the vacancy and notifies the Secretary of State for Justice of its choice. The Secretary of State for Justice then either

- approves the commission's selection

- rejects the commission's selection, or

- asks the commission to reconsider its selection.

If the Secretary of State for Justice approves the person selected by the commission, the Prime Minister must then recommend that person to the Monarch for appointment.[33]

New judges appointed to the Supreme Court after its creation will not necessarily receive peerages; however, they are given the courtesy title of Lord or Lady upon appointment.[25][34] The President and Deputy President are appointed to those roles rather than being the most senior by tenure in office.

List of current judges

There are 12 judges. In order of seniority, they are as follows:

| Portrait | Name | Born | Alma mater | Invested | Mandatory retirement |

Prior senior judicial roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.png) |

The Lord Reed of Allermuir (President) |

7 September 1956 (age 63) |

University of Edinburgh School of Law Balliol College, Oxford |

6 February 2012 | 7 September 2026 | Senator of the College of Justice: Inner House (2008–2012) Outer House (1998–2008) |

.jpg) |

Lord Hodge (Deputy President) |

19 May 1953 (age 67) |

Corpus Christi College, Cambridge University of Edinburgh School of Law |

1 October 2013 | 19 May 2023 | Senator of the College of Justice, Outer House (2005–2013) |

.jpg) |

The Lord Kerr of Tonaghmore |

22 February 1948 (age 72) |

Queen's University Belfast | 1 October 2009 | 22 February 2023 | Lord of Appeal in Ordinary (2009) Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland (2004–2009) Justice of the High Court (NI) (1993–2004) |

.jpg) |

Lady Black of Derwent |

1 June 1954 (age 66) |

Trevelyan College, Durham | 2 October 2017 | 1 June 2024 | Lady Justice of Appeal (2010–2017) Justice of the High Court, FD (1999–2010) |

.jpg) |

Lord Lloyd-Jones | 13 January 1952 (age 68) |

Downing College, Cambridge | 2 October 2017 | 13 January 2022 | Lord Justice of Appeal (2012–2017) Justice of the High Court, QBD (2005–2012) |

.jpg) |

Lord Briggs of Westbourne |

23 December 1954 (age 65) |

Magdalen College, Oxford | 2 October 2017 | 23 December 2024 | Lord Justice of Appeal (2013–2017) Justice of the High Court, CD (2006–2013) |

|

Lady Arden of Heswall |

23 January 1947 (age 73) |

Girton College, Cambridge Harvard Law School |

1 October 2018 | 23 January 2022 | Lady Justice of Appeal (2000–2018) Justice of the High Court, CD (1993–2000) |

.jpg) |

Lord Kitchin | 30 April 1955 (age 65) |

Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge | 1 October 2018 | 30 April 2025 | Lord Justice of Appeal (2011–2018) Justice of the High Court, CD (2005–2011) |

| Lord Sales | 11 February 1962 (age 58) |

Churchill College, Cambridge Worcester College, Oxford |

11 January 2019 | 11 February 2032 | Lord Justice of Appeal (2014–2018) Justice of the High Court, CD (2008–2014) | |

| Lord Hamblen | 23 September 1957 (age 62) |

St John's College, Oxford Harvard Law School |

13 January 2020 | 23 September 2027 | Lord Justice of Appeal (2016–2020) Justice of the High Court, QBD (2008–2016) | |

| Lord Leggatt | 12 November 1957 (age 62) |

King's College, Cambridge Harvard University City Law School |

21 April 2020 | 12 November 2027 | Lord Justice of Appeal (2018–2020)

Justice of the High Court, QBD (2012–2018) | |

| Lord Burrows | 17 April 1957

(age 63) |

Brasenose College, Oxford | 2 June 2020 | 17 April 2027 | None (First Justice to be appointed direct from academia)[35] |

Building

The court is housed in Middlesex Guildhall - which it shares with the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council—in the City of Westminster.

The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 gave time for a suitable building to be found and fitted out before the Law Lords moved out of the Houses of Parliament, where they had previously used a series of rooms in the Palace of Westminster.[36]

After a lengthy survey of suitable sites, including Somerset House, the Government announced that the new court would be at the Middlesex Guildhall, in Parliament Square, Westminster. That decision was examined by the Constitutional Affairs Committee,[37] and the grant of planning permission by Westminster City Council for refurbishment works was challenged in a judicial review by the conservation group Save Britain's Heritage.[38] It was also reported that English Heritage had been put under great pressure to approve the alterations.[39] Feilden + Mawson, supported by Foster & Partners, were the appointed architects.[40]

The building had been used as the Middlesex Quarter Sessions House, adding later its county council chamber, and lastly as a Crown Court centre.

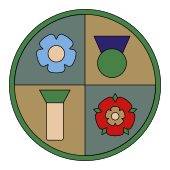

Badge

The official badge of the Supreme Court was granted by the College of Arms in October 2008.[41] It comprises both the Greek letter omega (representing finality) and the symbol of Libra (symbolising the scales of justice), in addition to the four floral emblems of the United Kingdom: a Tudor rose, representing England, conjoined with the leaves of a leek, representing Wales; a flax (or 'lint') blossom for Northern Ireland; and a thistle, representing Scotland.[42]

Two adapted versions of its official badge are used by the Supreme Court. One features the words "The Supreme Court" and the letter omega in black (in the official badge granted by the College of Arms, the interior of the Latin and Greek letters are gold and white, respectively), and displays a simplified version of the crown (also in black) and larger, stylised versions of the floral emblems; this modified version of the badge is featured on the new Supreme Court website,[43] as well as in the forms that will be used by the Supreme Court.[44] A further variant omits the crown entirely and is featured prominently throughout the building.[45]

Another emblem is formed from a more abstract set of depictions of the four floral emblems and is used in the carpets of the Middlesex Guildhall designed by Sir Peter Blake, creator of such works as the cover of The Beatles' 1967 album, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[46]

See also

- Courts of the United Kingdom

- Judgments of the Supreme Court, by year:

- List of House of Lords cases

- UKSCblog

References

- "Constitutional Reform Act 2005 (c. 4), Part 3, Section 23". The National Archives (United Kingdom). 24 March 2005. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- "The Supreme Court". The Registry, the Supreme Court (The Registry of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom). 12 January 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- "Departments, agencies and public bodies". GOV.UK. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Constitutional Reform: A Supreme Court for the United Kingdom". Department of Constitutional Affairs. July 2003. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "New Supreme Court opens with media barred". The Daily Telegraph. London. 1 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

For the first time, we have a clear separation of powers between the legislature, the judiciary and the executive in the United Kingdom. This is important. It emphasises the independence of the judiciary, clearly separating those who make the law from those who administer it.

- Wakeham report 2000, Chapter 9, Recommendation 57.

- "The Supreme Court is an unnecessary attack on the constitution". The Daily Telegraph. London. 1 October 2009. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

The Government argued that there must be a separation in order to comply with Article Six of the European Convention on Human Rights, which guarantees a fair trial.

- Rozenberg, Joshua (8 September 2009). "Fear over UK Supreme Court impact". BBC News.

- See A Le Sueur, 'From Appellate Committee to Supreme Court: A Narrative', chap 5 in L. Blom-Cooper, G. Drewry and B. Dickson (eds),The Judicial House of Lords (Oxford University Press, 2009); Queen Mary School of Law Legal Studies Research Paper No. 17/2009. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1374357

- "House of Lords - Constitutional Reform Bill - First Report". publications.parliament.uk.

- "Written Answer of the Ministry of Justice to question posed by Lord Steinberg (Col. WA102". Lords Hansard. 26 March 2008.

- "Panel numbers criteria". Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Dominic Casciani. "What is the UK Supreme Court?". BBC News.

- The 11 Supreme Court judges who ruled on UK's Brexit appeal, BBC News (24 January 2017).

- Owen Bowcott, Supreme court to hear claims suspension of parliament is unlawful, The Guardian (16 September 2019).

- Court, The Supreme. "Mark Ormerod to be Supreme Court's Chief Executive - The Supreme Court". www.supremecourt.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Court, The Supreme. "Executive Team - The Supreme Court". www.supremecourt.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "Constitutional Reform Act 2005: Section 48", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 2005 c. 4 (s. 48)

- "Scottish Court Service: An Introduction" (PDF). Scottish Court Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

The Supreme Courts are made up of the Court of Session, the High Court of Justiciary and the Accountant of Court's Office

- Peplow, Alex (15 July 2016). "A Curious Jurisdiction – Section 4 of the Judicial Committee Act 1833". UK Constitutional Law Association. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Constitutional Reform Act 2005, section 24

- "Justice of the UK Supreme Court". London, United Kingdom: 10 Downing Street. 20 April 2009. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Frances Gibb (23 July 2009). "Lord Neuberger named Master of the Rolls". The Times. London. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Frances Gibb (23 March 2010). "New Supreme Court justice – Sir John Dyson".

- "No. 59746". The London Gazette. 1 April 2011. pp. 6177–6178.

- "Press release: Courtesy titles for Justices of the Supreme Court" (PDF). Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. 13 December 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers appointed as senior Lord of Appeal in Ordinary". Archived from the original on 5 September 2008.

- Rozenberg, Joshua (24 June 2010). "Vacancy in the supreme court – and age could be a deciding factor – Joshua Rozenburg". the Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "Supreme Court judge dies aged 66". 27 June 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- Constitutional Reform Act 2005, section 38

- "Supreme Court selection process for President and Justices". The Supreme Court. 8 February 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "Supreme Court – new appointments process". Ministry of Justice. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- Constitutional Reform Act 2005, sections 25–31

- "Courtesy titles for Justices of the Supreme Court" (PDF). Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. 13 December 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- Court, The Supreme. "Swearing-in of The Right Honourable Professor Burrows QC as Justice of the Supreme Court - The Supreme Court". www.supremecourt.uk. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Truly the Supremes? Reflections on the New Court, UKSC Blog". Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- "Minutes of Oral Evidence Taken before the Constitutional Affairs Committee 17 April 2007". Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- "The Queen on the application of Save Britain's Heritage v. Westminster City Council". High Court (Administrative Court). Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- Binney, Marcus (22 June 2006). "Lord Falconer's supreme blunder". The Times. London. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- "Questions to the Department for Constitutional Affairs, 15 January 2007 (Col. 877W)". Commons Hansard.

- "The College of Arms Newsletter". College of Arms. December 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "New artwork: Supreme Court emblem". The Supreme Court. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "The Supreme Court". The Supreme Court. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- "Notice of appeal (or application for permission to appeal)" (PDF). www.supremecourt.uk.

- "In pictures: UK Supreme Court". BBC News. 15 July 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "Inside the UK Supreme Court". BBC News. 15 July 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

Further reading

- The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom: History, Art, Architecture Chris Miele ed. (Merrell) ISBN 978-1-85894-508-8

- Le Sueur, ed. (18 March 2004), Building the UK's New Supreme Court: National and Comparative Perspectives, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-926462-9, retrieved 16 May 2010

- Morgan, Derek (ed). Constitutional Innovation: the creation of a Supreme Court for the United Kingdom (A special issue of the Legal Studies, the Journal of the Society of Legal Scholars).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. |

- Official site

- Ministry of Justice, Supreme Court site

- "Grand designs". BBC News. 7 March 2007. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- UK Supreme Court: Much ado about nothing? in the Harvard Law Record

.svg.png)