1945 United Kingdom general election

The 1945 United Kingdom general election was a national election held on 5 July 1945, though polling in some constituencies was delayed by several days, while the counting of votes was delayed until 26 July to provide time for overseas votes to be brought to Britain. The governing Conservative Party sought to maintain their position within parliament, but faced challenges from public opinion about the future of the United Kingdom in the post-war period. Incumbent Prime Minister Winston Churchill proposed a call for a general election in Parliament, which passed with a majority vote less than two months after the conclusion of World War II in Europe.[1]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 640 seats in the House of Commons 321 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 72.8%, | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

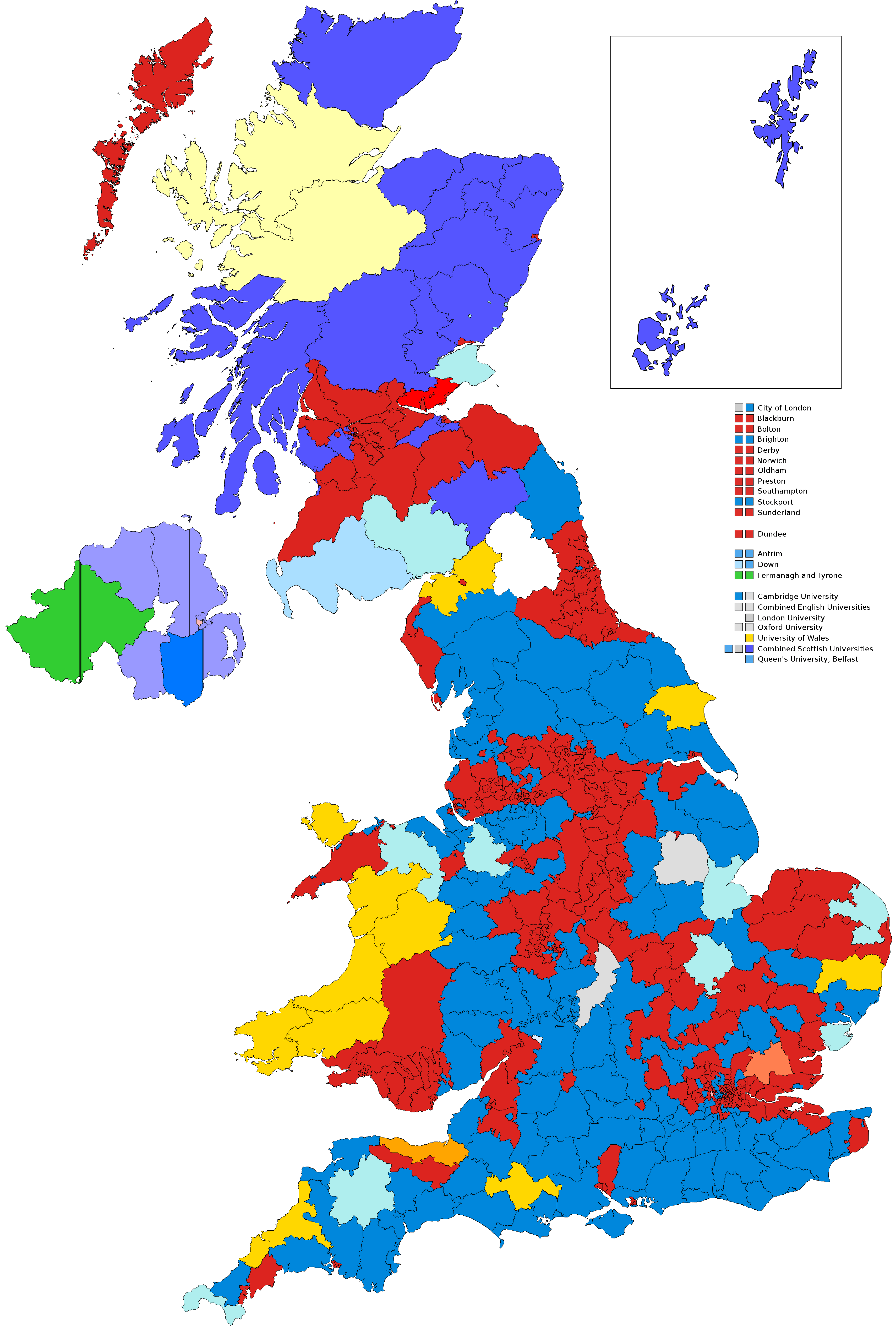

Colours denote the winning party—as shown in § Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

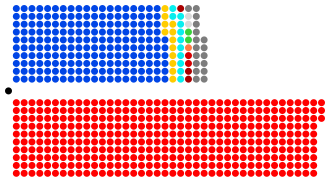

Composition of the House of Commons after the election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The political backdrop of the election's campaigning was focused on leadership of the country and its future. Churchill sought to use his wartime popularity as part of his campaign to keep the Conservatives in power, after spending it in a wartime coalition since 1940 with the other political parties, but faced questions from public opinion surrounding the Conservatives' actions in the 1930s and Churchill's ability to handle domestic issues unrelated to warfare. Clement Attlee, who led the Labour Party, was seen as a more competent leader amongst voters, particularly by those who feared a return to the levels of unemployment in the 1930s and sought a strong figurehead in British politics to lead the rebuilding of the country after the war. Opinion polls when the election was called showed strong approval ratings for Churchill, but Labour had been gradually gaining support for months prior to the war's conclusion.

The final result of the election showed Labour to have won a landslide victory,[2] making a net gain of 239 seats and winning 47.7%, thus allowing Attlee to be appointed prime minister. For the Conservatives, the Labour victory was a shock,[3] as they suffered a net loss of 189 seats despite winning 36.2% of the vote, having campaigned on the mistaken belief that Churchill would win as people praised his progression of the war. For the other two major parties, the Liberal Party faced a serious blow after taking a net loss of 9 seats with a vote share of 9.0%, many within urban areas and including the seat held by its leader Sir Archibald Sinclair. The National Liberal Party fared significantly worse, enduring a net loss of 22 seats with a vote share of 2.9%, with its leader Ernest Brown losing his seat.

The election was the first in which Labour won a majority, and allowed Attlee to begin implementing the party's post-war reforms for the country.[4] The swing to their party from the Conservatives of 10.7% is the largest since the Acts of Union 1800 – relatedly, the Conservative loss of the vote exceeded that of the 1906 Liberal landslide ousting of a Conservative administration. Churchill remained actively involved in politics and would return as prime minister, leading his party into the 1951 general election. For the National Liberals, the election was their last as they merged with the Conservatives in 1947; Brown resigned from politics in the aftermath of the election.

Dissolution of Parliament and campaign

Held less than two months after VE Day, it was the first general election since 1935, as general elections had been suspended during the Second World War. Clement Attlee, Leader of the Labour Party, refused Winston Churchill's offer of continuing the wartime coalition until the Allied defeat of Japan. King George VI dissolved Parliament, which had been sitting for ten years without an election, on 15 June.

The Labour manifesto, "Let Us Face the Future" included promises of nationalisation, economic planning, full employment, a National Health Service, and a system of social security. The Conservative manifesto, "Mr. Churchill's Declaration to the Voters", on the other hand, included progressive ideas on key social issues but was relatively vague on the idea of post-war economic control;[5] having been associated with high levels of unemployment in the 1930s,[6] they failed to convince voters that they could effectively deal with it in a post-war Britain.[7] In May 1945, the month in which the war in Europe ended, Churchill's approval ratings stood at 83%, although the Labour Party held an 18% lead as of February 1945.[6]

The polls for some seats were delayed until 12 July and in Nelson and Colne until 19 July, because of local wakes weeks.[8] The results were counted and declared on 26 July, to allow time to transport the votes of those serving overseas. Victory over Japan Day ensued on 15 August.

Outcome

The caretaker government led by Churchill was heavily defeated; the Labour Party under Attlee's leadership won a landslide victory, gaining a majority of 145 seats. This was the first election in which Labour gained a majority of seats, and also the first time it won a plurality of votes.

The election was a disaster for the Liberal Party; it lost all its urban seats, marking its transition from being a party of government to a party of the political fringe.[9] Its leader, Archibald Sinclair, lost his rural seat of Caithness and Sutherland. This was the last general election until 2019 where a major party leader lost their seat, although Sinclair lost only by a handful of votes in a very tight three-way contest.

The National Liberal Party fared even worse, losing two-thirds of its seats and falling behind the Liberals in seat count for the first time since the parties split in 1931. This was the final election that the Liberal Nationals fought as an autonomous party, as they merged with the Conservative Party two years later, continuing to exist as a subsidiary party of the Conservatives until 1968.

Future prominent figures who entered Parliament included Harold Wilson, James Callaghan, Barbara Castle, Michael Foot, and Hugh Gaitskell. Future Conservative prime minister Harold Macmillan lost his seat, returning to Parliament at a by-election later in the year.

Reasons for the Labour victory

Ralph Ingersoll reported in late 1940:

"Everywhere I went in London people admired [Churchill's] energy, his courage, his singleness of purpose. People said they didn't know what Britain would do without him. He was obviously respected. But no one felt he would be Prime Minister after the war. He was simply the right man in the right job at the right time. The time being the time of a desperate war with Britain's enemies".[10]

Historian Henry Pelling, noting that polls showed a steady Labour lead after 1942, pointed to long-term forces that caused the Labour landslide: the usual swing against the party in power; the Conservative loss of initiative; wide fears of a return to the high unemployment of the 1930s; the theme that socialist planning would be more efficient in operating the economy; and the mistaken belief that Churchill would continue as prime minister regardless of the result.[11]

Labour strengths

The greatest factor in Labour's dramatic win appeared to be their policy of social reform. In one opinion poll, 41% of respondents considered housing to be the most important issue that faced the country, 15% stated the Labour policy of full employment, 7% mentioned social security, 6% nationalisation, and just 5% international security, which was emphasised by the Conservatives.

The Beveridge Report, published in 1942, proposed the creation of a welfare state. It called for a dramatic turn in British social policy, with provision for nationalised healthcare, expansion of state-funded education, National Insurance, and a new housing policy. The report was extremely popular, and copies of its findings were widely purchased, turning it into a best-seller. The Labour Party adopted the report eagerly,[3] while the Conservatives accepted many of the principles of the report (Churchill did not regard the reforms as socialist), but claimed that they were not affordable.[12] Labour offered a new comprehensive welfare policy, reflecting a consensus that social changes were needed.[4] The Conservatives were not willing to make the same changes that Labour proposed, and hence appeared out of step with public opinion.

Labour played to the concept of "winning the peace" that would follow the Second World War. Possibly for this reason, there was especially strong support for Labour in the armed services, who feared the unemployment and homelessness to which the soldiers of the First World War had returned. It has been claimed that the pro-left-wing bias of teachers in the armed services was a contributing factor, but this argument has generally not carried much weight, and the failure of the Conservative governments in the 1920s to deliver a "land fit for heroes" was likely more important.[4]

The role of propaganda films produced during the war, which were shown to both military and civilian audiences, is also seen as a contributory factor due to their general optimism about the future, which meshed with the Labour Party's campaigning in 1945 better than with that of the Conservatives.[13] Writer and soldier Anthony Burgess remarked that Churchill—who often wore a colonel's uniform at this time—himself was not nearly as popular with soldiers at the front as with officers and civilians: he noted that Churchill often smoked cigars in front of soldiers who had not had a decent cigarette in days.[14]

Labour had also been given, during the war, the opportunity to display to the electorate their domestic competence in government, under men such as Attlee as Deputy Prime Minister, Herbert Morrison at the Home Office, and Ernest Bevin at the Ministry of Labour.[5] The differing strategies of the two parties during wartime likewise gave Labour an advantage. Labour continued to attack pre-war Conservative governments for their inactivity in tackling Hitler, reviving the economy, and re-arming Britain,[15] while Churchill was less interested in furthering his party, much to the chagrin of many of its members and MPs.[6]

Conservative weaknesses

Though voters respected and liked Churchill's wartime record, they were more distrustful of the Conservative Party's domestic and foreign policy record in the late 1930s.[5] Churchill and the Conservatives are also generally considered to have run a poor campaign in comparison to Labour. As Churchill's personal popularity remained high, the Conservatives were confident of victory and based much of their election campaign on this, rather than proposing new programmes. However, people distinguished between Churchill and his party—a contrast which Labour repeatedly emphasised throughout the campaign. Voters also harboured doubts over Churchill's ability to lead the country on the domestic front.[4]

In addition to the poor Conservative general election strategy, Churchill went so far as to accuse Attlee of seeking to behave as a dictator, in spite of Attlee's service as part of Churchill's war cabinet. In the most famous incident of the campaign, Churchill's first election broadcast on 4 June backfired dramatically and memorably. Denouncing his former coalition partners, he declared that Labour "would have to fall back on some form of a Gestapo" to impose socialism on Britain.[16] Attlee responded the next night by ironically thanking the prime minister for demonstrating to people the difference between Churchill the great wartime leader and Churchill the peacetime politician, and argued the case for public control of industry.

Another blow to the Conservative campaign was the memory of the 1930s policy of appeasement, which had been conducted by Churchill's Conservative predecessors, Neville Chamberlain and Stanley Baldwin, and was at this stage widely discredited for allowing Adolf Hitler's Germany to become too powerful.[4] Labour had strongly advocated appeasement until 1938, but the inter-war period had been dominated by Conservatives. With the exception of two brief minority Labour governments in 1924 and 1929–1931, the Conservatives had been in power for its entirety. As a result, the Conservatives were generally blamed for the era's mistakes, not merely for appeasement but for the inflation and unemployment of the Great Depression.[4] Many voters felt that while the war of 1914–1918 had been won, the peace that followed had been lost.

Results

| 393 | 197 | 12 | 11 | 27 |

| Labour | Conservative | Lib | LN | Other |

| Candidates | Votes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Leader | Stood | Elected | Gained | Unseated | Net | % of total | % | No. | Net % | |

| Labour | Clement Attlee | 603 | 393 | 242 | 3 | +239 | 61.4 | 47.7 | 11,967,746 | +9.7 | |

| Conservative | Winston Churchill | 559 | 197 | 14 | 204 | −190 | 30.8 | 36.2 | 8,716,211 | −11.6 | |

| Liberal | Archibald Sinclair | 306 | 12 | 5 | 14 | −9 | 1.9 | 9.0 | 2,177,938 | +2.3 | |

| Liberal National | Ernest Brown | 49 | 11 | 0 | 22 | −22 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 686,652 | −0.8 | |

| Independent | N/A | 38 | 8 | 6 | 0 | +6 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 133,191 | +0.5 | |

| National | N/A | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | +1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 130,513 | +0.2 | |

| Common Wealth | C. A. Smith | 23 | 1 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 110,634 | N/A | |

| Communist | Harry Pollitt | 21 | 2 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 97,945 | +0.3 | |

| Nationalist | James McSparran | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 92,819 | +0.2 | |

| National Independent | N/A | 13 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 65,171 | N/A | |

| Independent Labour | N/A | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 63,135 | +0.2 | |

| Ind. Conservative | N/A | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | +2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 57,823 | +0.1 | |

| Ind. Labour Party | Bob Edwards | 5 | 3 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 46,769 | −0.5 | |

| Independent Progressive | N/A | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 45,967 | +0.1 | |

| Independent Liberal | N/A | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | +2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 30,450 | +0.1 | |

| SNP | Douglas Young | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.1 | 26,707 | −0.1 | |

| Plaid Cymru | Abi Williams | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 16,017 | N/A | |

| Commonwealth Labour | Harry Midgley | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 14,096 | N/A | |

| Independent Nationalist | N/A | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 5,430 | N/A | |

| Liverpool Protestant | H. D. Longbottom | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 2,601 | N/A | |

| Christian Pacifist | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 2,381 | N/A | |

| Democratic | Norman Leith-Hay-Clark | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 1,809 | N/A | |

| Agriculturist | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 1,068 | N/A | |

| Socialist (GB) | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 472 | N/A | |

| United Socialist | Guy Aldred | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 0.0 | 300 | N/A | |

Votes summary

Seats summary

Transfers of seats

This differs from the above list in including seats where the incumbent was standing down and therefore there was no possibility of any one person being defeated. The aim is to provide a comparison with the previous election. All comparisons are with the 1935 election.

- In some cases the change is due to the MP defecting to the gaining party. Such circumstances are marked with a *.

- In other circumstances the change is due to the seat having been won by the gaining party in a by-election in the intervening years, and then retained in 1945. Such circumstances are marked with a †.

- Candidate had defected to National Liberal party.

- Seat had been won by an Independent Labour candidate in a by-election, who fought and won the 1945 election as a Labour candidate.

- Seat had been won by an independent candidate in a by-election, who fought and won the 1945 election as a Labour candidate.

- Seat had been won by an independent candidate in a by-election.

- Candidate had moved to 'National' label.

- Seat had been won by Independent Conservative candidate in a by-election, who fought and won the 1945 election as a National Independent candidate.

- Candidate had defected to the Common Wealth party.

- Seat had been won by National Labour in a by-election.

See also

References

- McCallum, R. B.; Readman, Alison (1964). The British General Election of 1945. Nuffield Studies.

- Rowe 2004, p. 37.

- "1945: Churchill loses general election". BBC. 26 July 1945. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- Lynch 2008, p. 4.

- Thomas & Willis 2016, pp. 154–155.

- Addison, Paul (29 April 2005), Why Churchill Lost in 1945, BBC, retrieved 22 February 2009

- Bogdador, Vernon (23 September 2014), The General Election, 1945 (Lecture), Museum of London, retrieved 26 May 2018

- General Election (Polling Date): 31 May 1945: House of Commons debates, They Work For You

- Baines 1995.

- Ingersoll 1940, p. 127.

- Pelling 1980, pp. 399–414.

- Lynch 2008, p. 10.

- Spurr, Sean. "1945 General Election". HistoryEmpire.com. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- Burgess 1987, p. 305.

- Lynch 2008, pp. 1–4.

- Marr 2008, pp. 5–6.

- "Voter turnout at UK general elections 1945–2015". UK Political Info.

Sources

- Burgess, Anthony (1987), Little Wilson and Big God, Heinemann, ISBN 1446452557, retrieved 1 September 2014

- Ingersoll, Ralph (1940), Report on England, November 1940, New York: Simon and Schuster

- Lynch, Michael (2008), "1. The Labour Party in Power 1945–51", Britain 1945–2007, Access to History, Hodder Headline, ISBN 978-0-340-96595-5

- McCallum, R. B. and Alison Readman. The British General Election of 1945 (Nuffield Studies) (1964)

- Marr, Andrew (2008), A History of Modern Britain, Pan Macmillan Ltd., pp. 5–6, ISBN 978-0-330-43983-1

- Pelling, Henry (1980), "The 1945 general election reconsidered", Historical Journal, 23 (2): 399–414, doi:10.1017/S0018246X0002433X, JSTOR 2638675

- Rowe, Chris (2004), Britain 1929–1998, Heinemann, ISBN 978-0-435-32738-5

- Thomas, Jo; Willis, Michael (2016), Wars and Welfare: Britain in Transition 1906–1957, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-8354-598

Further reading

- Addison, Paul (1975), The Road to 1945: British politics and the Second World War, London: Cape

- Baines, Malcolm (1995), "The liberal party and 1945 general election", Contemporary Record, 9 (1): 48–61, doi:10.1080/13619469508581327

- Brooke, Stephen (1992), Labour's war: the Labour party during the Second World War, Oxford University Press

- Burgess, Simon (1991), "1945 Observed – A History of the Histories", Contemporary Record, 5 (1): 155–170, doi:10.1080/13619469108581164, historiography

- Craig, F. W. S. (1989), British Electoral Facts: 1832–1987, Dartmouth: Gower, ISBN 0900178302

- Fielding, Steven (1992), "What did 'the people' want?: the meaning of the 1945 general election", Historical Journal, 35 (3): 623–639, doi:10.1017/S0018246X00026005, JSTOR 2639633

- Fry, Geoffrey K. (1991), "A Reconsideration of the British General Election of 1935 and the Electoral Revolution of 1945", History, 76 (246): 43–55, doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1991.tb01533.x

- Gilbert, Bentley B. (1972), "Third Parties and Voters' Decisions: The Liberals and the General Election of 1945", Journal of British Studies, 11 (2): 131–141, doi:10.1086/385629

- Kandiah, Michael David (1995), The conservative party and the 1945 general election, pp. 22–47

- McCallum, R. B.; Readman, Alison (1947), The British general election of 1945, the standard scholarly study

- McCulloch, Gary (1985), "Labour, the Left, and the British General Election of 1945", Journal of British Studies, 24 (4): 465–489, doi:10.1086/385847, JSTOR 175476

- Nicholas, H. (1951), The British general election of 1950, London: Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-77865-0

- Pelling, Henry (1980), "The 1945 general election reconsidered", Historical Journal, 23 (2): 399–414, doi:10.1017/S0018246X0002433X, JSTOR 2638675

- Toye, Richard (2010), "Winston Churchill's 'Crazy Broadcast': Party, Nation, and the 1945 Gestapo Speech" (PDF), Journal of British Studies, 49 (3): 655–680, doi:10.1086/652014, hdl:10871/9424, JSTOR 23265382

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1945 United Kingdom general election. |

- Catalogue of general election ephemera held at LSE Archives

- "Labour Wins". Melbourne Argus. 27 July 1945.

- United Kingdom election results—summary results 1885–1979

Manifestos

- Mr. Churchill's Declaration of Policy to the Electors, 1945 Conservative Party manifesto

- Let Us Face the Future, 1945 Labour Party manifesto

- 20 Point Manifesto of the Liberal Party, 1945 Liberal Party manifesto

.jpg)