British passport

The British passport is the travel document issued by the United Kingdom to individuals holding any form of British nationality. It grants the bearer international passage in accordance with visa requirements and serves as proof of citizenship. It also facilitates access to consular assistance from British embassies around the world. Passports are issued using royal prerogative, which is exercised by Her Majesty's Government. British citizen passports have been issued in the UK by Her Majesty's Passport Office, a division of the Home Office, since 2006. All passports issued in the UK since 2006 have been biometric.

| British passport | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Front cover of the series B British passport, issued between March 2019 and March 2020 | |

_data_page.png) The polycarbonate data page of the current Series C British biometric passport | |

| Type | Passport |

| Issued by | —HM Passport Office —CSRO (Gibraltar) —Crown dependencies —Overseas Territories |

| First issued | 1414 (First mention of 'passport' in an Act of Parliament)[1] 1915 (Photo passport) 1921 (Hardcover booklet) 15 August 1988 (Machine-readable passport) 5 October 1998 (Version 2) 6 March 2006 (Series A biometric passport) 5 October 2010 (Version 2) 7 December 2015 (Series B) 10 March 2020 (Series C) |

| Purpose | Identification, International travel |

| Eligibility | British citizens British Overseas Territories citizens British Overseas citizens British subjects British National (Overseas) British protected persons |

| Expiration | adult: 10 years child: 5 years |

| Cost | Adult (16 or older)[2][3][4]

Standard |

The legacy of the United Kingdom as an imperial power has resulted in several types of British nationality, and different types of British passport exist as a result. All British passports enable the bearer to request consular assistance from British embassies and from certain Commonwealth embassies in some cases. British citizens can use their passport as evidence of right of abode in the United Kingdom.

Although citizens of the UK and Gibraltar are no longer considered citizens of the European Union, the British citizen and Gibraltar passports allow for freedom of movement in any of the states of the European Economic Area and Switzerland until the EU withdrawal transition period ends on 31 December 2020.

Between 1920 and 1988, the standard design of British passports was a navy blue hardcover booklet featuring the royal coat of arms emblazoned in gold. From 1988, the UK adopted machine readable passports in accordance with the International Civil Aviation Organization standard 9303. At this time, the passport colour was changed to burgundy red, in line with most other EEC passports. The first generation of machine-readable passports attracted significant criticism for their perceived flimsiness, mass-produced nature and sudden deviation from the traditional design.[5]

Since the introduction of biometric passports, the British passport has introduced a new design every five years.[6] March 2020 saw the introduction of a new navy blue passport with a continuity design based on the last 1988 issue. This design is being phased in over a number of months, and when introduced, the plan was that all passports issued should be blue by mid-2020.[7][8][9][10]

History

| Timeline | |

|---|---|

Various changes to the design were made over the years:[11]

| |

Early passports (1414–1921)

British passports issued in 1857 (left) and 1862 (right). |

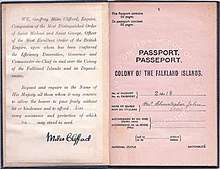

King Henry V of England is credited with having invented what some consider the first passport in the modern sense, as a means of helping his subjects prove who they were in foreign lands. The earliest reference to these documents is found in the Safe Conducts Act 1414.[21][22] In 1540, granting travel documents in England became a role of the Privy Council of England, and it was around this time that the term "passport" was introduced. In Scotland, passports were issued by the Scottish Crown and could also issued on the Crown's behalf by burghs, senior churchmen and noblemen.[23] Passports were still signed by the monarch until 1685, when the Secretary of State could sign them instead. The Secretary of State signed all passports in place of the monarch from 1794 onwards, at which time formal records started to be kept; all of these records still exist. Passports were written in Latin or English until 1772, then in French until 1858. Since that time, they have been written in English, with some sections translated into French. In 1855, passports became a standardised document issued solely to British nationals. They were a simple single-sheet hand-drafted paper document.

Some duplicate passports and passport records are available at the British Library; for example IOR: L/P&J/11 contain a few surviving passports of travelling ayahs from the 1930s.[24] A passport issued on 18 June 1641 and signed by King Charles I still exists.[11]

Starting in the late 19th century, an increasing number of Britons began travelling abroad due to the advent of railways and travel services such as the Thomas Cook Continental Timetable. The speed of trains, as well as the number of passengers that crossed multiple borders, made enforcement of passport laws difficult, and many travellers did not carry a passport in this era.[25] However, the outbreak of World War I led to the introduction of modern border controls, including in the UK with passage of the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914. Thus, in 1915 the British government developed a new format of passport that could be mass-produced and used to quickly identify the bearer. The new passport consisted of a printed sheet folded into eight and affixed to a clothed cardboard cover. It included a description of the holder as well as a photograph, and had to be renewed after two years.

Passport booklets (1921–1993)

In October 1920, the League of Nations held the Paris Conference on Passports & Customs Formalities and Through Tickets. British diplomats joined with 42 countries to draft passport guidelines and a general booklet design resulted from the conference.[26] The League model specified a 32-page booklet of 15.5 cm by 10.5 cm (6.1 inches by 4.1 inches). The first four pages were reserved for detailing the bearer's physical characteristics, occupation and residence.

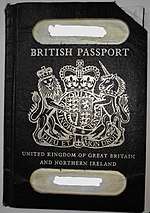

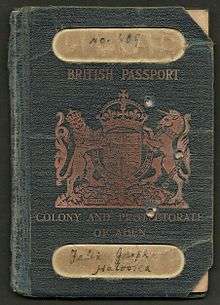

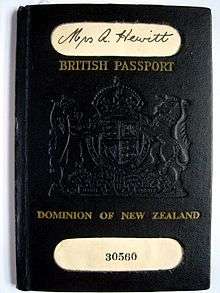

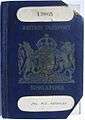

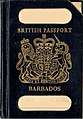

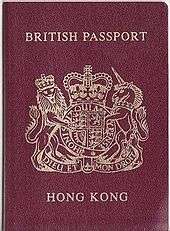

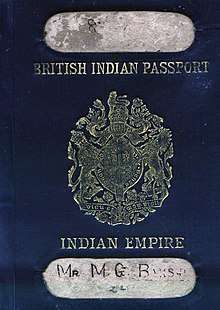

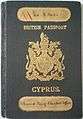

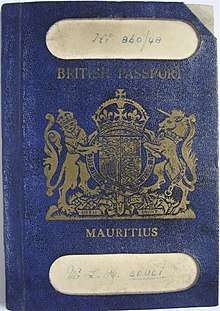

The British government formed the Passport Service in the same year and in 1921 began issuing 32-page passports with a navy blue hardcover with an embossed coat of arms. "BRITISH PASSPORT" was the common identifier printed at the top of all booklets, while the name of the issuing government was printed below the coat of arms (e.g. United Kingdom, New Zealand, Hong Kong). Cut-outs in the cover allowed the bearer's name and the passport number to be displayed. This format would remain the standard for most British passports until the introduction of machine-readable passports in 1988. It continued to be issued in the United Kingdom until the end of 1993.

As with many contemporary travel documents worldwide, details were handwritten into the passport and (as of 1955) included: number, holder's name, "accompanied by his wife" and her maiden name, "and" (number) "children", national status. For both bearer and wife: profession, place and date of birth, country of residence, height, eye and hair colour, special peculiarities, signature and photograph. Names, birth dates, and sexes of children, list of countries for which valid, issue place and date, expiry date, a page for renewals and, at the back, details of the amount of foreign exchange for travel expenses (a limited amount of sterling, typically £50 but increasing with inflation, could be taken out of the country).[27] The bearer's sex was not explicitly stated, although the name was written in with title ("Mr John Smith"). Descriptive text was printed in both English and French (a practice which still continues), e.g., "Accompanied by his wife (Maiden name)/Accompagné de sa femme (Née)". Changed details were struck out and rewritten, with a rubber-stamped note confirming the change.

If details and photograph of a man's wife and details of children were entered (this was not compulsory), the passport could be used by the bearer, wife, and children under 16, if together; separate passports were required for the wife or children to travel independently.[28] The passport was valid for five years, renewable for another five, after which it had to be replaced.[29]

Renewal of a passport required physical cancellation of the old passport, which was then returned to the bearer. The top-right corner of its front cover was cut off and "Cancelled" was stamped into one or both of the cut-outs in the front cover, which showed the passport number and the bearer's name, as well on the pages showing the bearer's details and the document's validity.

For much of the 20th century, the passport had a printed list of countries for which it was valid, which was added to manually as validity increased. A passport issued in 1955 was valid for the British Commonwealth, USA, and all countries in Europe "including the USSR, Turkey, Algeria, Azores, Canary Islands, Iceland, and Madeira";[30] during its period of validity restrictions eased and it was endorsed "and for all other foreign countries".[31]

The British visitor's passport

A new simplified type, the British Visitor's Passport, was introduced in 1961. It was a single sheet of cardboard, folded in three so as to consist of six pages the same size as those of a regular passport, and was valid for one year. It was obtainable for many years from Employment Exchanges, as agents of the Passport Office, and later from a Post Office. It was accepted for travel by most west European countries (excluding surface travel to West Berlin), but was dropped in 1995 since it did not meet new security standards. A cancelled passport, which was returned to the bearer, had its top-right corner cut off, which had the effect of removing a corner from every page.

Machine-readable passports (1988–2006)

.jpg)

After the passport standardisation efforts of the 1920s, further effort to update international passport guidance was limited. The United Kingdom joined the European Economic Community in 1973, at a time when the Community was looking to strengthen European civic identity.[32] Between 1974 and 1975, the member states developed a common format. Member states agreed that passports should be burgundy in colour and feature the heading "European Community" in addition to the country name. Adoption was by member states was voluntary.[33] While most of the Community adopted the format by 1985, the UK continued to issue the traditional blue booklet.

Rapid growth of air travel and technological change led to the International Civil Aviation Organization defining a new international standard for machine-readable passports, ICAO Doc 9303, in 1980.[34] An ICAO standard machine-readable passport was a significant departure from the traditional British passport layout, and the British government did not immediately adopt it. In 1986, the United States announced the US Visa Waiver Program. The concept allowed for passport holders of certain countries to enter the US for business or tourism without applying for a visitor visa. The UK was the first country to join the scheme in 1988; however, a requirement was that the traveller hold a machine-readable passport.[35][36] Thus, the British government was, after nearly 70 years, forced to retire the traditional navy blue League of Nations format passport.

With the move to machine-readable passports, the UK decided to adopt the European Community format. On 15 August 1988, the Glasgow passport office became the first to issue burgundy-coloured machine-readable passports. They had the words 'European Community' on the cover, later changed to 'European Union' in 1997. The passport had 32 pages; while a 48-page version was made available with more space for stamps and visas. Two lines of machine-readable text were printed in ICAO format, and a section was included in which relevant terms ("surname", "date of issue", etc.) were translated into the official EU languages. Passports issued overseas did not all have a Machine Readable Zone, but these were introduced gradually as appropriate equipment was made available overseas.

While other British territories such as Hong Kong and the Cayman Islands were not part of the European Community, they also adopted the same European format, although "British Passport" remained at the top rather than "European Community".

In 1998[37] the first digital image passport was introduced with photographs being replaced with images printed directly on the data page which was moved from the cover to an inside page to reduce the ease of fraud. These documents were all issued with machine-readable zones and had a hologram over the photograph, which was the first time that British passports had been protected by an optically variable safeguard. These documents were issued until 2006, when the biometric passport was introduced.

Biometric passports (2006–present)

Series A (2006–2015)

In the late 1990s, ICAO's Technical Advisory Group began developing a new standard for storing biometric data (e.g. photo, fingerprints, iris scan) on a chip embedded in a passport. The September 11 attacks involving the hijacking of commercial airliners led to the rapid incorporation of the group's technical report in to ICAO Doc 9303.[38]

The Identity and Passport Service issued the first biometric British passport on 6 February 2006, known as Series A. This was the first British passport to feature artwork. Series A, version 1 was produced between 2006 and 2010, while an updated version 2 with technical changes and refreshed artwork was produced between 2010 and 2015.[39]

Version 1 showcased birds native to the British Isles. The bio-data page was printed with a finely detailed background including a drawing of a red grouse, and the entire page was protected from modification by a laminate which incorporates a holographic image of the kingfisher; visa pages were numbered and printed with detailed backgrounds including drawings of other birds: a merlin, curlew, avocet, and red kite. An RFID chip and antenna were visible on the official observations page and held the same visual information as printed, including a digital copy of the photograph with biometric information for use with facial recognition systems. The Welsh and Scottish Gaelic languages were included in all British passports for the first time,[40] and appeared on the titles page replacing the official languages of the EU, although the EU languages still appeared faintly as part of the background design. Welsh and Scottish Gaelic preceded the official EU languages in the translations section.[39]

In 2010, Her Majesty's Passport Office signed a ten-year, £400 million contract with De La Rue to produce British passports.[41] This resulted in Series A, version 2, which introduced minor security enhancements. The biometric chip was relocated from the official observations page to inside the cover, and the observations page itself was moved from the back of the passport to immediately after the data page. All new art was produced for version 2, this time with a coastal theme. Data and visa pages featured coastal scenes, wildlife and meteorological symbols.[39]

Renewal of the passport required physical cancellation of the old passport, which was then returned to the bearer. The top-right corners of its front and back covers were cut off, as well as the top-right corner of the final pair of pages, which had been bound in plastic with the bearer's details and a digital chip; a white bar-coded form stating "Renewal" and the bearer's personal details was stuck onto the back cover.

.jpg)

Series B (2015–2020)

HMPO's contract with De La Rue involved the design of a new generation of biometric passport, which was released in October 2015 as the Series B passport. The cover design remained the same as Series A, with minor changes to the cover material. The number of pages of a standard passport was increased from 32 to 34, and the 50-page 'jumbo' passport replaced the previous 48-page business passport. New security features included rich three-dimensional UV imagery, cross-page printing and a single-sheet bio-data page joined with the back cover. At the time of its introduction, no other passport offered visa free access to more countries than the UK Series B British passport.[42]

The theme of the Series B passport was 'Creative United Kingdom', and HMPO described the Series B artwork as the most intricate ever featured in a British passport. Each double-spread page set featured artwork celebrating 500 years of achievements in art, architecture and innovation in the UK. Ordnance Survey maps were also printed inside featuring places related to the imagery. A portrait of William Shakespeare was embedded in each page as a watermark.[42]

The Series B passport was initially issued to British citizens with "European Union" printed on the cover. However, new stocks of the Series B from March 2019 onwards removed the reference in anticipation of withdrawal from the union. The premature change was controversial given the uncertainty and division in the UK during 2019.[43]

Series C (2020–present)

The introduction of the burgundy machine-readable passport between 1988 and 1993 had been met with significant resistance. The burgundy passports attracted criticism for their perceived flimsiness, mass-produced nature and sudden deviation from the traditional design.[5] There was speculation regarding re-introduction of the old-style passport following the UK's withdrawal from the European Union.[44] but the government denied any immediate plans.[45] Such a change was supported by some due to its symbolic value, including Brexit Secretary David Davis,[46] while others thought the undue weight put on such a trivial change raises the question of whether the government is able to prioritise its order of business ahead of Brexit.[47] Nevertheless, the British passport was due for an update in 2020, as the existing De La Rue passport contract was due to expire.

On 2 April 2017, Michael Fabricant MP said that De La Rue had stated that the coat of arms would "contrast better on navy blue than it currently does on the maroon passports"[48] as part of their pre-tender discussions with the government.[49][50] In December 2017, Immigration Minister Brandon Lewis announced that the blue passport would "return" after exit from the EU.[7]

Following open tender under EU public procurement rules in 2018, the Franco-Dutch security firm Gemalto was selected over British banknote and travel document printer De La Rue. The result of the tender proved highly controversial, as it saw the production of British passport blanks moved from Gateshead in the UK to Tczew, Poland.[51][52][53]

On 10 March 2020, the new Series C blue British passport officially began to be issued. Series B passports will also be issued while the Home Office uses up old stock, but the Government expects that all new passports will be Series C by mid-2020.[10]

Series C introduces a polycarbonate laser-engraved bio-data page with an embedded RFID chip. Also embedded in the data page is a decoding lens which optically unscrambles information hidden on the official observations page and inner front cover. The reverse of the polycarbonate data page serves as the title page and features a portrait-orientation photo of the bearer, reminiscent of pre-1988 passports. Series C features very little artwork, with a compass rose being the only printed art. The passport has the national flowers of England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales embossed on the back cover.

National identity cards

Second World War

.png)

The National Registration Act established a National Register which began operating on 29 September 1939 (National Registration Day). This introduced a system of identity cards, and a requirement that they must be produced on demand or presented to a police station within 48 hours. Identity cards had to be carried by every man, woman, and child at all times. They included information such as name, age, address, and occupation.

Prior to National Registration Day, 65,000 enumerators across the country delivered forms which householders were required to record their details on. On the following Sunday and Monday the enumerators visited every household, checked the form before issuing a completed identity card for each of the residents. All cards at this time were the same brown/buff colour.

Three main reasons for their introduction:

- 1. The major dislocation of the population caused by mobilisation and mass evacuation and also the wartime need for complete manpower control and planning in order to maximise the efficiency of the war economy.

- 2. The likelihood of rationing (introduced from January 1940 onwards).

- 3. Population statistics. As the last census had been held in 1931, there was little accurate data on which to base vital planning decisions. The National Register was in fact an instant census and the National Registration Act closely resembles the 1920 Census Act in many ways

On 21 February 1952, it no longer became necessary to carry an identity card. The National Registration Act of 1939 was repealed on 22 May 1952.

Abandoned plans for "next generation" biometric passports and national identity registration

There had been plans, under the Identity Cards Act 2006, to link passports to the Identity Cards scheme. However, in the Conservative – Liberal Democrat Coalition Agreement that followed the 2010 General Election, the new government announced that they planned to scrap the ID card scheme, the National Identity Register, and the next generation of biometric passports, as part of their measures "to reverse the substantial erosion of civil liberties under the Labour Government and roll back state intrusion".[54][55]

The Identity Cards Act 2006 would have required any person applying for a passport to have their details entered into a centralised computer database, the National Identity Register, part of the National Identity Scheme associated with identity cards and passports. Once registered, they would also have been obliged to update any change to their address and personal details. The identity card was expected to cost up to £60 (with £30 going to the Government, and the remainder charged as processing fees by the companies that would be collecting the fingerprints and photographs).[56] In May 2005 the Government said that the cost for a combined identity card and passport would be £93 plus processing fees.[57]

The next generation of biometric passports, which would have contained chips holding facial images and fingerprints,[58] were to have been issued from 2012. Everyone applying for a passport from 2012 would have had their 10 fingerprints digitally scanned and stored on a database, although only two would have been recorded in the passport.[59]

Nobody in the UK is required to carry any form of ID. In everyday situations most authorities, such as the police, do not make spot checks of identification for individuals, although they may do so in instances of arrest.

Five Nations Passport Group

Since 2004, the United Kingdom has participated in the Five Nations Passport Group, an international forum for cooperation between the passport issuing authorities in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States to "share best practices and discuss innovations related to the development of passport policies, products and practices".[60]

Types of British passports

Owing to the many different categories in British nationality law, there are different types of passports for each class of British nationality. All categories of British passports are issued by Her Majesty's Government under royal prerogative.[61] Since all British passports are issued in the name of the Crown, the reigning monarch does not require a passport.[62] The following table shows the number of valid British passports on the last day of 2019 and shows the different categories eligible to hold a British passport:[63]

| Category | Country code | Valid passports as at 31 Dec 2019 |

Issuing authority |

|---|---|---|---|

| British citizens | GBR | 51,116,513 | HM Passport Office (UK); Civil Status and Registration Office (Gibraltar); HMPO on behalf of the Crown Dependencies |

| British Overseas Territories CitizensA (Gibraltar) | GBD | 2,240 | CSRO |

| British Overseas Territories Citizens (other Overseas Territories) | 61,151 | HMPO on behalf of individual Overseas Territories[64] | |

| British Overseas citizens | GBO | 12,192 | HMPO |

| British subjects with right of abode in UK | GBS | 31,659 | |

| British subjects without right of abode in UK | 795 | ||

| British protected persons | GBP | 1,252 | |

| British Nationals (Overseas) | GBN | 314,779 |

^A Formerly British Dependent Territories Citizens.

British citizen, British Overseas citizen, British subject, British protected person, British National (Overseas)

British citizen, British Overseas citizen, British subject, British protected person and British National (Overseas) passports are issued by HM Passport Office in the UK. British nationals of these categories applying for passports outside the UK can apply for their passport online from HMPO. British passports were previously issued by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in British embassies around the world. However, in 2009, this was stopped and British citizen passports can now only be issued by the Passport Office in the UK. The FCO says: "In their 2006 report on consular services, the National Audit Office recommended limiting passport production to fewer locations to increase security and reduce expenditure."[65]

Gibraltar

British citizens and British Overseas Territory citizens of Gibraltar can apply for their passport in Gibraltar, where it will be issued by the Gibraltar Civil Status and Registration Office. British citizens can still live, work, and study in Gibraltar at any time, as British citizenship grants right of abode in Gibraltar.

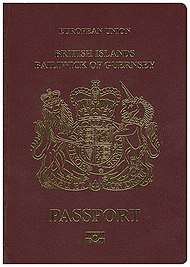

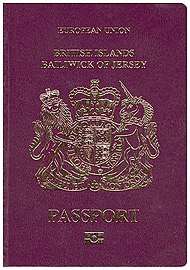

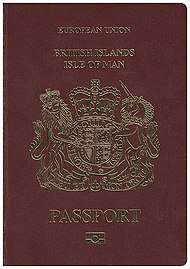

Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories

British passports in Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man are issued in the name of the Lieutenant-Governor of the respective Crown Dependencies on behalf of the States of Jersey, States of Guernsey and the Government of the Isle of Man respectively. Meanwhile, in British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territories Citizen passports are issued in the name of the respective territory's governor.

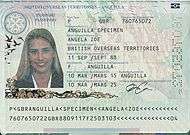

The nationality reads for Overseas Territories "British Overseas Territories Citizen" regardless of the residence of the bearer. Previously, in the machine-readable zone, the three-letter ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 code of the territory is given in the field of the code of issuing state, while GBD (British Overseas Territories citizens, formerly British Dependent Territories citizens) is shown in the nationality field. Either of these features enabled automatic distinction between BOTCs related to different territories. Ever since the HMPO assumed the responsibility of the issuance of BOTC passports in 2015, however, the code of issuing state is changed to GBD for all territories, thus making it impossible to identify the holder's domicile without the aid of other features, such as the passport cover.[66]

Special British passports

Diplomatic passports are issued in the UK by HMPO. They are issued to British diplomats and high-ranking government officials to facilitate travel abroad.

Official passports are issued to those travelling abroad on official state business.

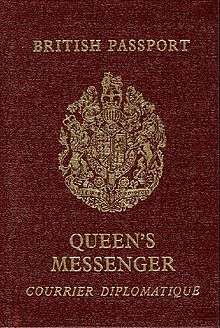

Queen's Messenger passports were issued to diplomatic couriers who transport documents on behalf of HM Government. Since 2014, these have been replaced by an observation within a standard diplomatic passport.

Emergency passports are issued by British embassies across the world. Emergency passports may be issued to any person holding British nationality. Commonwealth citizens are also eligible to receive British emergency passports in countries where their country of nationality is unrepresented. Under a reciprocal agreement, British emergency passports may also be issued to EU citizens in countries where their own country does not have a diplomatic mission or is otherwise unable to assist.

.jpg)

Collective (also known as group) passports are issued to defined groups of 5 to 50 individuals who are British citizens under the age of 18 for travel together to the EEA and Switzerland, such as a group of school children on a school trip.[67]

EU passports

British citizens, British Overseas Territory citizens of Gibraltar and British subjects with right of abode are considered to be UK nationals for the purpose of EU law. They were therefore considered to be EU citizens until 31 January 2020 when the UK withdrew from the EU. As a result, passports issued to these nationals were considered to be EU passports. British passports with EU status facilitated access to consular assistance from another European Union member state.

British nationals formerly holding EU status continue to enjoy free movement within the European Economic Area and Switzerland until the Brexit transition period ends 31 December 2020 or later. The right to live, and work in the Republic of Ireland will continue for British citizens, as the British citizens are not treated as aliens under Irish law. Common Travel Area arrangements for visa-free travel remain unchanged. Other types of British national were not considered to be EU citizens, but may nevertheless enjoy visa-free travel to the European Union on a short-term basis.

Physical appearance

Outside cover

Current issue British passports are navy blue or burgundy. Blue passports are being phased in since March 2020, and burgundy passports are also issued while the Home Office uses up old stock.[10] The blue passports sports the coat of arms of the United Kingdom emblazoned in the centre of the front cover.

"BRITISH PASSPORT" is inscribed above the coat of arms, and the name of the issuing government is inscribed below (e.g. "UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND" or "TURKS AND CAICOS ISLANDS"). Where a British national is connected to a territory that is no longer under British sovereignty (e.g. BN(O) in Hong Kong), the issuing government is the United Kingdom. The biometric passport symbol ![]()

Burgundy passports issued by the UK, Gibraltar and the Crown Dependencies follow a different format, as they are based on the EU common model. The words "UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND" (+ "GIBRALTAR" where relevant) or "BRITISH ISLANDS" (+ the Dependency's name) are inscribed above the coat of arms, whilst the word "PASSPORT" is inscribed below. The biometric passport symbol ![]()

Function-related passports

Besides the ordinary passports described above, special passports are issued to government officials from which diplomatic status may (diplomatic passport) or may not (official passport) be conferred by the text on the cover. Until 2014 a special passport was available for a Queen's Messenger, which had on its cover the text "QUEEN’S MESSENGER – COURRIER DIPLOMATIQUE" below the coat of arms and the text "BRITISH PASSPORT" above it.[68]

Each passport cover is detailed in the gallery below.

Inside cover

UK issue British passports contain on their inside cover the following words in English only:

Her Britannic Majesty's Secretary of State Requests and requires in the Name of Her Majesty all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance, and to afford the bearer such assistance and protection as may be necessary.

In older passports, more specific reference was made to "Her Britannic Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs", originally including the name of the incumbent. In non-UK issue passports, the request is made by the governor or lieutenant-governor of the territory in "the Name of Her Britannic Majesty".

Information page

British passports issued by HM Passport Office include the following data on the information page:

- Photograph of the owner/holder (digital image printed on page)

- Type (P)

- Code of issuing state (GBR)

- Passport number

- Surname (see note below regarding titles)

- Given names

- Nationality (the class of British nationality, such as "British Citizen" or "British Overseas Citizen", or if issued on behalf of a Commonwealth country, "Commonwealth Citizen"[69])

- Date of birth

- Sex (Gender)

- Place of birth (only the city or town is listed, even if born outside the UK; places of birth in Wales are entered in Welsh upon request [70])

- Date of issue

- Authority

- Date of expiry

- Machine-readable zone starting with P< GBR

The items are identified by text in English and French (e.g., "Date of birth/Date de naissance"), and there is a section in which all this text is translated into Welsh and Scottish Gaelic.[71] Passports issued until March 2019 were translated into all official EU languages.

According to the UK government, the current policy of using noble titles on passports requires that the applicant provides evidence that the Lord Lyon has recognised a feudal barony, or the title is included in Burke's Peerage. If accepted (and if the applicant wishes to include the title), the correct form is for the applicant to include the territorial designation as part of their surname (Surname of territorial designation e.g. Smith of Inverglen). The official observation would then show the holder's full name, followed by their feudal title e.g. The holder is John Smith, Baron of Inverglen.

Official Observations page

Certain British passports are issued with printed endorsements on the Official Observations page, usually in upper case (capital letters). They form part of the passport when it is issued, as distinct from immigration stamps subsequently entered in the visa pages. Some examples are:[72][73]

- The Holder is not entitled to benefit from European Union provisions relating to employment or establishment

- British citizens from Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man without a qualifying connection to the United Kingdom by descent or residency for more than five years have this endorsement in their passports. Moreover, British Nationals (Overseas) would have the same endorsement if they renew their BN(O) passport after 29 March 2019. This observation will cease to be used from 1 January 2021. [74]

- The Holder of this passport has Hong Kong permanent identity card no XXXXXXXX which states that the holder has the right of abode in Hong Kong

- British Nationals (Overseas) (BN(O)s) have this endorsement in their passports, as registration as a BN(O) before 1997 required the applicant to hold a valid Hong Kong permanent identity card, which guaranteed the holder's right of abode in Hong Kong. Such persons would continue to have right of abode or right to land in Hong Kong after the transfer of sovereignty of Hong Kong in 1997 under the Immigration Ordinance. This endorsement is also found in a British citizen passport when the holder has both British citizenship and BN(O) status.[73]

- The Holder is entitled to right of abode in the United Kingdom

- British Subjects with the right of abode (usually from Ireland) have this endorsement in their passports.

- The Holder is entitled to readmission in the United Kingdom

- British Overseas Citizens who have been granted indefinite leave to enter or remain after 1968 retain this entitlement for life as their ILR is not subject to the two-year expiration rule,[75] and their passports are accordingly issued with this endorsement.

- The Holder is subject to control under the Immigration Act 1971

- British nationals without the right of abode in the UK will have this endorsements in their passports unless they have been granted indefinite leave to enter or remain. However, even though a BN(O) passport does not entitle the holder the right of abode in the UK, this endorsement is not found in BN(O) passports (1999 and biometric versions).

- In accordance with the United Kingdom immigration rules the holder of this passport does not require an entry certificate or visa to visit the United Kingdom

- This endorsement is found in BN(O) passports, and accordingly holders of BN(O) passports are allowed to enter the UK as a visitor without an entry certificate or visa for up to six months per entry.

- The Holder is also a British National (Overseas)

- British citizens who also possess BN(O) status will have this endorsement in their passports to signify their additional status, as the two passports cannot be held at the same time.[73]

- The Holder is or The Holder is also known as ...

- This endorsement is found in passports where the holder uses or retains another professional, stage or religious name and is known by it "for all purposes", or has a recognised form of address, academic, feudal or legal title (e.g. Doctor, European Engineer, Queen's Counsel, Professor, Minister of Religion) regarded as important identifiers of an individual.[72] The styling 'Dr ...', 'Professor ...' or similar is recorded here, or the alternative professional/stage/religious name, usually on request by the passport holder.[72] For example, Cliff Richard's birth name was Harry Webb, and the passport Observations page would read:

"The Holder is also known as Cliff Richard"

- This endorsement is also found in the passport of persons with Peerage titles, members of the Privy Council, holders of knighthoods and other decorations, etc, to declare the holder's title.

- Also, this endorsement is found if the passport holder's name is too long to fit within the 30-character limits (including spaces) on the passport information page; applies to each line reserved for the surname and the first given name including any middle name(s).[76] In this scenario the holder's full name will be written out in full on the Observations page.[76] According to the UK passport agency guidelines, a person with a long or multiple given name, which cannot fit within the 30-character passport information page limits, should enter as much of the first given name, followed by the initials of all middle names (if any).[76] The same advice applies to a long or multiple surname. The holder's full name is then shown printed out in its entirety on the passport Observations page.[72][76] For example, Kiefer Sutherland's birth name would read on the passport information page:

Surname: "Sutherland"

Given names: "Kiefer W F D G R"

- Observations page:

"The Holder is Kiefer William Frederick Dempsey George Rufus Sutherland"

- The holder's name in Chinese Commercial Code: XXXX XXXX XXXX

- This endorsement was found in BN(O) and Hong Kong British Dependent Territories Citizen passports held by BN(O)s and British Dependent Territories Citizens with a connection to Hong Kong who have a Chinese name recognised by the Hong Kong Immigration Department before the handover. After the handover, British passport issued in Hong Kong can only be issued at the British Consulate-General, and this endorsement is no longer in use. (See also: Chinese commercial code)

- Holder is a dependant of a member of Her Britannic Majesty's Diplomatic Service

- This endorsement is found in British passports held by people who are dependants or spouses of British diplomats.

Multiple passports

People who have valid reasons may be allowed to hold more than one passport booklet. This applies usually to people who travel frequently on business, and may need to have a passport booklet to travel on while the other is awaiting a visa for another country. Some Muslim-majority countries including Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Kuwait, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Yemen do not issue visas to visitors if their passports bear a stamp or visa issued by Israel, as a result of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. In that case, a person can apply for a second passport to avoid travel issues. Reasons and supporting documentation (such as a letter from an employer) must be provided.[77]

In addition, a person who has dual British citizenship and British Overseas Territories citizenship are allowed to hold two British passports under different statuses at the same time. Persons who acquired their BOTC status with a connection to Gibraltar or Falkland Islands, however, are not eligible due to differences in regulations, and their BOTC passports will be cancelled when their British citizen passports are issued even when they possess both citizenships.[73]

Monarch

The Queen, Elizabeth II, does not have a passport because passports are issued in her name and on her authority, thus making it superfluous for her to hold one.[78] All other members of the royal family, however, including the Queen's husband Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh and their son, heir apparent Charles, Prince of Wales, do have passports.[78]

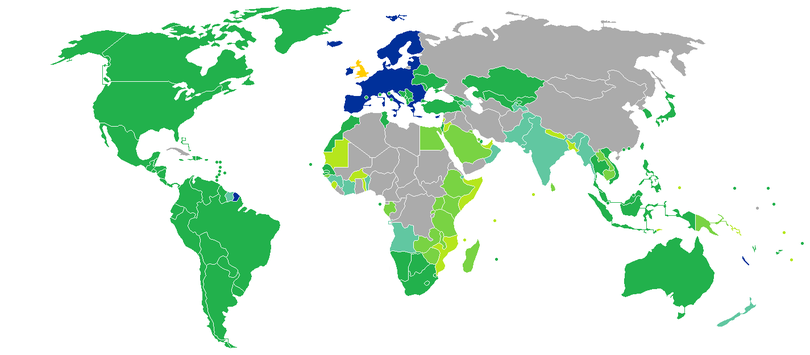

Visa requirements

Visa requirements for British citizens are administrative entry restrictions by the authorities of other states placed on citizens of the United Kingdom. As of 26 March 2019, holders of regular British Citizen passports had visa-free or visa on arrival access to 185 countries and territories, ranking the British Citizen passport 5th in the world in terms of travel freedom (tied with Austrian, Dutch, Norwegian, Portuguese and Swiss passports) according to the Henley Passport Index.[79] Additionally, Arton Capital's Passport Index ranked the British Citizen passport 3rd in the world in terms of travel freedom, with a visa-free score of 164 after Turkey was recently added (tied with Austrian, Belgian, Canadian, Greek, Irish, Japanese, Portuguese and Swiss passports), as of 17 October 2018.[80]

Visa requirements for other categories of British nationals, namely British Nationals (Overseas), British Overseas Citizens, British Overseas Territories Citizens, British Protected Persons, and British Subjects, are different.

Foreign travel statistics

According to the Foreign travel advice provided by the British Government (unless otherwise noted) these are the numbers of British visitors to various countries per annum in 2015 (unless otherwise noted):[81]

- Data for 2014

- Data for 2017

- Data for 2015

- Data for 2016

- Counting only guests in tourist accommodation establishments.

- Data for 2011

- Data for 2018

- Data for arrivals by air only.

- Data for 2012

- Data for 2013

- Data for 2009

- Data for 2010

- Data for 2019

- Data for 2005

- Total number includes tourists, business travelers, students, exchange visitors, temporary workers and families, diplomats and other representatives and all other classes of nonimmigrant admissions (I-94).

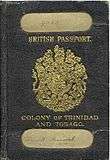

Gallery of British Passports

- British Overseas Territories Passports

_new.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Manx passport

Manx passport_new.jpg)

.jpg) Saint Helena passport

Saint Helena passport.jpg)

Contemporary British Overseas Territories biodata page

Contemporary British Overseas Territories biodata page

- Official and Diplomatic Passports

British biometric diplomatic passport

British biometric diplomatic passport British biometric official passport

British biometric official passport

- Emergency Passports

Series C emergency passport

Series C emergency passport- Series B emergency passport

- Previously Issued Passports

.jpg) British Citizen passport issued between 30 March 2019 and early 2020 (non-EU design issued to all British National including British Citizens)

British Citizen passport issued between 30 March 2019 and early 2020 (non-EU design issued to all British National including British Citizens) British Citizen passport issued prior to 30 March 2019 (last EU design issued to British Citizens)

British Citizen passport issued prior to 30 March 2019 (last EU design issued to British Citizens) British non-biometric passport issued between 1997 and 2006

British non-biometric passport issued between 1997 and 2006.jpg) First British machine-readable passport issued between 1988 and 1997

First British machine-readable passport issued between 1988 and 1997 Last British non-machine readable passport issued prior to 1988

Last British non-machine readable passport issued prior to 1988 1920s United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland passport

1920s United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland passport

1940 Colony of Aden passport

1940 Colony of Aden passport

1949 Maltese passport

1949 Maltese passport 1951 Singapore passport

1951 Singapore passport 1957 Federation of Malaya passport

1957 Federation of Malaya passport 1958 British Hong Kong passport

1958 British Hong Kong passport- 1959 Grenadian passport

Pre-1990 Hong Kong British Dependent Territories Citizen (BDTC) passports

Pre-1990 Hong Kong British Dependent Territories Citizen (BDTC) passports 1997 Hong Kong BDTC passport

1997 Hong Kong BDTC passport Falkland Islands passport

Falkland Islands passport British Guiana passport

British Guiana passport

British Cyprus passport - older version

British Cyprus passport - older version

1942 British consular emergency travel document issued to a refugee in Turkey during WWII

1942 British consular emergency travel document issued to a refugee in Turkey during WWII Cardboard identity card issued under arrangements regarding collective passports by the UK Passport Agency in 2001

Cardboard identity card issued under arrangements regarding collective passports by the UK Passport Agency in 2001

See also

References

- Nisbet, Gemma (23 September 2014). "The history of the passport". The West Australian.

- "Passport fees – GOV.UK".

- Free if born before 2 September 1929

- Upgrade fees may still apply.

- BBC Newsnight. "Paxman on the new EU passport (Newsnight archives 1995)". YouTube. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- HM Passport Office. "New UK passport design". GOV.UK. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Blue passport to return after Brexit". BBC News. 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- "New blue British passport rollout to begin in March". BBC News. 22 February 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Blue British passports to return in March". BBC News. 22 February 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Changes to the design of British passports". gov.uk. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Passport history timeline 1414–present". IPS. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- "Brexit: 50 things the UK needs to do after triggering Article 50". CNN. 29 March 2017.

- "Passport history timeline 1414–present". UK Gov Home Office. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "Passports" (PDF). gov.uk. Retrieved 7 April 2016. (see paragraph 6.5)

- Identity & Passport Service (25 August 2010). "New passport design unveiled". Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- Tucker, Emma (3 November 2015). "UK creatives feature in updated British passport design". Dezeen. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Introducing the new UK passport design (PDF). HM Passport Office. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- Osborne, Simon. "Blue passports RETURN". Daily Express. Express Newspapers. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "UK passport: A new travel document for 2019". Gemalto. Gemalto NV. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "'Iconic' blue UK passports to be issued from next month after EU exit". Sky News. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Benedictus, Leo (18 November 2006). "A brief history of the passport". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Casciani, Dominic (25 September 2008). "Analysis: The first ID cards". BBC. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "Family History – My ancestor was a passport holder". scan.org.uk. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "British Library: Asians in Britain: Ayahs, Servants and Sailors". Bl.uk. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (10 April 2014). "History of Passports". aem. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Quito, Anne. "The design of every passport in the world was set at one 1920 meeting". Quartz. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Printed information from 1955 passport

- 1955 British passport, Notes section at back: "A passport including particulars of the holder's wife is not available for the wife's use when she is travelling alone."

- 1955 British passport, Notes section at back: "... available for five years in the first instance, ... may be renewed for further periods ... provided ... ten years from the original date is not exceeded."

- 1955 passport, printed on page 4

- 1955 British passport, Notes section at back: "... only available for travel to the countries named on page 4, but may be endorsed for other countries. ... available for travelling to territory under British protection or trusteeship not including the Aden Protectorate."

- "A People's Europe – Historical events in the European integration process (1945–2014) – CVCE Website". www.cvce.eu. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "The European passport – Historical events in the European integration process (1945–2014) – CVCE Website". www.cvce.eu. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Machine Readable Travel Documents" (PDF). International Civil Aviation Organization. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Visa Waiver Program Requirements". Department of Homeland Security. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Wasem, Ruth Ellen. "The US Visa Waiver Program Facilitating Travel and Enhancing Security" (PDF). Chatham House. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Identity and Passport Service | Home Office". Ips.gov.uk. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- "Doc 9303 – Machine Readable Travel Documents Seventh Edition, 2015" (PDF). International Civil Aviation Orgnaization. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Basic Passport Checks" (PDF). Her Majesty's Passport Office. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "The United Kingdom Passport Service – Welsh and Scottish Gaelic in UK Passports". National Archives. 8 February 2005. Archived from the original on 20 June 2005. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- "New passport design hits the streets". GOV.UK.

- "Introducing the new UK passport design" (PDF). Her Majesty's Passport Office. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- O'Carroll, Lisa (6 April 2019). "Javid defends removal of words 'European Union' from passports". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Brexit: Blue passport may actually be reintroduced once Britain leaves EU, from The Independent on 13 September 2016, accessed on 19 February 2017

- "After Brexit, is it time to bring back the traditional British passport?". Birmingham Mail. 4 August 2016.

- "Cabinet minister backs return of blue passports". The Telegraph. 4 October 2016.

- Bringing back blue passports is nostalgia gone mad – we've got bigger things to worry about from The Telegraph on 14 September 2016, accessed on 19 February 2017

- Wheeler, Caroline (3 April 2017). "Return of the great British blue passport: £500million project will replace EU document | UK | News". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- "New passport tender issued". PrintWeek. 7 April 2017.

- "Dark blue British passport could return after Brexit in £490m revamp". ITV. 2 April 2017.

- Stewart, Heather; Rawlinson, Kevin (22 March 2018). "Post-Brexit passports set to be made by Franco-Dutch firm". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "Britain won't make its new Brexit passports. Guess who will?". CNN Money. 22 March 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Humiliation, says Priti Patel, as blue Brexit-era passports to be made by Franco-Dutch firm". The Times. 22 March 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Conservative Liberal Democrat Coalition Agreement Archived 15 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Conservative Party, Published May 12, 2010, Accessed May 13, 2010

- Conservative Liberal Democrat Coalition Agreement Archived 11 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Liberal Democrats, Published May 12, 2010, Accessed May 13, 2010

- "Retailers reject ID security fear". BBC News. 6 May 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Tempest, Matthew (25 May 2005). "ID card cost soars as new bill published". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- IBM inks UK biometric passport deal TG Daily, published July 10, 2009, accessed May 13, 2010

- "IPS will keep images of fingerprints". Kable.co.uk. 19 May 2009. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- "International Comparison". 18 September 2011. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "The issuing, withdrawal or refusal of passports – Written statements to Parliament – GOV.UK".

- "Passports". The home of the Royal Family. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- "FOICR 57241 Luke Lo final response" (PDF). 11 February 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- "Overseas Territories Passports To Be Printed In The UK From July 15 | Government of the Virgin Islands". www.bvi.gov.vg. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "Passports for Britons resident in Chile issued from USA". FCO. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- "UK passport office blamed for travel woes". royalgazette.com.

- "Collective (group) passports". GOV.UK. Government Digital Service. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Cover of a Queen's Messenger's passport". Council of the European Union. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- "United Kingdom Border Agency: Immigration Directorates' Instructions, Chapter 22, Section 2(3)" (PDF). Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- "Welsh language" (PDF). Identity and Passport Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- "Welsh and Scottish Gaelic in UK Passports". Identity and Passport Service. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- "Guidance: Observations in passports" (PDF). HM Passport Office. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "British National (Overseas) and British Dependent Territories Citizens" (PDF). HM Passport Office. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Renew your passport – gov.je, 9 February 2020.

- "CHAPTER 22 SECTION 2 UNITED KINGDOM PASSPORTS" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. November 2004. p. 4. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- "GOV.UK: Name to appear on passport?". GOV.UK, HM Passport Office. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "How to apply for a second UK passport". Business Traveller. 2 May 2019.

- Berry, Ciara (15 January 2016). "Passports".

- "Global Ranking – Visa Restriction Index 2020" (PDF). Henley & Partners. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "Global Passport Power Rank – The Passport Index 2019". Passport Index – All the world's passports in one place.

- "Foreign travel advice".

- "Annual review of visitor arrivals in pacific island countries — 2017" (PDF). South Pacific Tourism Organization. June 2018.

- "Statistical Yearbook". American Samoa Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- "Anuário de Estatística do Turismo 2015 — Angola" (in Portuguese). Ministry of Hotels and Tourism, Angola. 2016. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017.

- "Visitor Arrivals by Country of Residence".

- "Tourism Statistics – IAATO".

- "Tourism Statistics for Antigua and Barbuda".

- "Number of Stayover Visitors by Market".

- "Info" (PDF). www.tourism.australia.com. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Trade and Media – Holidays in Austria. Travel Information of the Austrian National Tourist Office" (PDF). Austriatourism.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- "Number of foreign citizens arrived to Azerbaijan by countries".

- "Stopovers by Country" (PDF).

- "Annual report" (PDF). corporate.visitbarbados.org. 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Tourisme selon pays de provenance 2016". Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "Visitor Statistics". gotobermuda.com. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- Namgay, Phunstho. "Annual Reports – Tourism Council of Bhutan". www.tourism.gov.bt.

- "INE – Instituto Nacional de Estadística – Turismo".

- TOURISM STATISTICS Cumulative data, January – December 2017

- "Tourism Statistics Annual Report 2015" (PDF).

- "Demanda Turstica Internacional Slides 2017" (PDF). Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- "Brunei Darussalam Tourism Report 2011" (PDF).

- "Arrivals of visitors from abroad to Bulgaria by months and by country of origin – National statistical institute". www.nsi.bg.

- Abstract of Statistics. Chapitre 19 Statistiques du tourismep. 280

- "Tourism Statistics Report".

- "Statement | Ministry of tourism". Ministry of tourism.

- "Service bulletin International Travel: Advance Information" (PDF). statcan.gc.ca.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- CIDOT. "Welcome to the Cayman Islands Department of Tourism (CIDOT) Destination Statistics Website".

- "Estadísticas".

- "China Inbound Tourism Statistics in 2015".

- "Tourists in China by country of origin 2017 – Statistic". Statista.

- The data obtained on request. Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo de Colombia Archived 6 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- (in French) http://www.apicongo.org/code/Annuaire_statistique_du_tourisme_Congo_2012.pdf

- "Visitor Arrivals by Country of Usual Residence".

- "Informes Estadísticos – Instituto Costarricense de Turismo – ICT". www.ict.go.cr.

- TOURIST ARRIVALS AND NIGHTS IN 2017

- "Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información, Sitio en Actualización |" (PDF) (in Spanish). One.cu. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Monthly Statistics".

- "Statistical Service – Services – Tourism – Key Figures". www.mof.gov.cy.

- "Tourism – 4th quarter of 2017 – CZSO". www.czso.cz.

- "2015 Visitors Statistics Report" (PDF).

- "BCRD – Estadísticas Económicas". Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "ACCOMMODATED TOURISTS BY COUNTY AND COUNTRY OF RESIDENCE (MONTHS)".

- Amitesh. "PROVISIONAL VISITOR ARRIVALS – 2017 – Fiji Bureau of Statistics". www.statsfiji.gov.fj.

- Tuominen, Marjut. "Statistics Finland -". www.stat.fi.

- "Stats". www.entreprises.gouv.fr. 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Données détaillées".

- "Tourism, transport and communication summary" (PDF).

- "International Travel (Residence) (2018)".

- Tourismus in Zahlen 2016, Statistisches Bundesamt

- "Hellenic Statistical Authority. Non-residents arrivals from abroad 2015".

- "Overnight stays by month, nationality, region, unit and time". Statistikbanken.

- "Video: 2017 Records Over 10,000 More Stayover Visitors Than 2016". 25 January 2018.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "TOURISM IN HUNGARY 2016". Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- "Passengers through Keflavik airport by citizenship and month 2002-2018-PX-Web". Px.hagstofa.is. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Badan Pusat Statistik". Bps.go.id. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Countrywise". tourism.gov.in. 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Overseas Visitors to Ireland January–December 2012–2015" (PDF).

- TOURIST ARRIVALS TO ISRAEL (EXC. DAY VISITORS & CRUISE PASSENGERS) BY NATIONALITY, Ministry of Tourism

- "IAGGIATORI STRANIERI NUMERO DI VIAGGIATORI". Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- "Monthly Statistics – Jamaica Tourist Board". www.jtbonline.org.

- "2017 Foreign Visitors & Japanese Departures" (PDF). Japan National Tourism Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- "Tourist Overnight and Same Day Visitors By Nationality during".

- "Статистические сборники". stat.gov.kz.

- Administrator. "Visitors by Country of Residence". Archived from the original on 19 March 2016.

- "Туризм в Кыргызстане – Архив публикаций – Статистика Кыргызстана". www.stat.kg.

- "Statistical Reports on Tourism in Laos". Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "TUG02. Visitors staying in hotels and other accommodation establishments by country of residence-PX-Web".

- "Arrivals according to nationality during year 2016".

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Number of guests and overnights in Lithuanian accommodation establishments. '000. All markets. 2015–2016".

- "Arrivals by touristic region and country of residence (All types of accommodation) 2011 – 2016". www.statistiques.public.lu.

- "DSEC – Statistics Database".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "TOURIST ARRIVALS TO MALAYSIA BY COUNTRY OF NATIONALITY DECEMBER 2017" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "Number of visitors by country, 2009" (PDF).

- "December 2017 – Ministry of Tourism". www.tourism.gov.mv.

- "Inbound Tourism: December 2018" (PDF).

- "ANNUAIRE 2014".

- Carrodeguas, Norfi. "Datatur3 – Visitantes por Nacionalidad".

- Statistică, Biroul Naţional de (12 February 2018). "// Comunicate de presă". www.statistica.md. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "2017 ОНЫ ЖИЛИЙН ЭЦСИЙН МЭДЭЭГ 2016 ОНТОЙ ХАРЬЦУУЛСАН МЭДЭЭ".

- "data" (PDF). monstat.org. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Tourist arrivals by country of residence" (PDF).

- "Study" (PDF). www.observatoiredutourisme.ma. 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Myanmar Tourism Statistics – Ministry of Hotels and Tourism, Myanmar". Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- "Tourism Statistics 2015 p.34" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2017.

- "Visitors arrival by country of residence and year". Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- "Stats" (PDF). www.stat.gov.mk. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Toerisme in perspectief 2018

- "International travel and migration: December 2017". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- "Estadísticas de Turismo".

- "Info". www.omantourism.gov.om. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Pakistan Statistical Year Book 2012 – Pakistan Bureau of Statistics".

- "Immigration / Tourism Statistics – Palau National Government".

- "Data" (PDF). www.atp.gob.pa. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "datosTurismo". datosturismo.mincetur.gob.pe.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "in 2016 – tables TABL. III/6. NON-RESIDENTS VISITING POLAND IN 2016 AND THEIR EXPENDITURE" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- "2017 Annual Tourism Performance Report" (PDF).

- "Data" (PDF). www.insse.ro. February 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Въезд иностранных граждан в РФ". Fedstat.ru. 18 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- "Statistics Netherlands".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Statistics" (PDF). www.discoversvg.com. 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Entrada de Visitantes/ S. Tomé e Príncipe Ano 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- "Office of the Republic of Serbia, data for 2018" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2018.

- "National Bureau of Statistics". www.nbs.gov.sc.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Data". slovak.statistics.sk. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Visitor Statistics, 2015–2017" (PDF).

- "Report" (PDF). www.statssa.gov.za. 2002. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Korea, Monthly Statistics of Tourism – key facts on tourism – Tourism Statistics".

- "Número de turistas según país de residencia(23984)". www.ine.es.

- "TOURIST ARRIVALS BY COUNTRY OF RESIDENCE 2017" (PDF).

- "Suriname Tourism Statistics" (PDF). www.surinametourism.sr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "Swaziland Tourism – Swaziland Safari – Swaziland Attractions – Useful Links – Research".

- "Tillväxtverkets Publikationer -". Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- "Visitor Arrivals by Nationality".

- "The 2016 International Visitors' Exit Survey Report. International Tourist Arrivals. p. 73-77" (PDF). nbs.go.tz/. NBS Tanzania. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- "สถิติด้านการท่องเที่ยว ปี 2560 (Tourism Statistics 2017)". Ministry of Tourism & Sports. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Stats, Tonga. "Migration Statistics – Tonga Stats".

- "T&T – Stopover Arrivals By Main Markets 1995-YTD" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- "DISTRIBUTION OF ARRIVING FOREIGN VISITORS (2016–2018) JANUARY-DECEMBER". Archived from the original on 14 July 2019.

- "Turks and Caicos sto-over arrivals" (PDF).

- Dev1. "2016 annual visitor arrivals review" (PDF).

- "MINISTRY OF TOURISM, WILDLIFE AND ANTIQUITIES SECTOR STATISTICAL ABSTRACT,2014". Archived from the original on 7 May 2016.

- "Foreign citizens who visited Ukraine in 2017 year, by countries". www.ukrstat.gov.ua.

- Statistics for the Emirate of Dubai

Dubai Statistics, Visitor by Nationality - "Table 28 – Homeland Security".

- "Распределение въехавших в Республику Узбекистан иностранных граждан по странам в 2015 году". data.gov.uz. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "International visitors to Viet Nam in December and 12 months of 2017". Vietnam National Administration of Tourism. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Downloads". Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Passports of the United Kingdom. |