1992 United Kingdom general election

The 1992 United Kingdom general election was held on Thursday 9 April 1992, to elect 651 members to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. The election resulted in the fourth consecutive victory for the Conservative Party since 1979 and would be the last time that the Conservatives would win an overall majority at a general election until 2015. This election result took many by surprise, as opinion polling leading up to the election day had shown the Labour Party, under leader Neil Kinnock, consistently, if narrowly, ahead.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

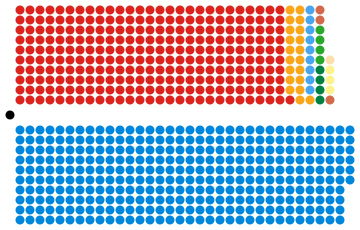

All 651 seats in the House of Commons 326 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 77.7% ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

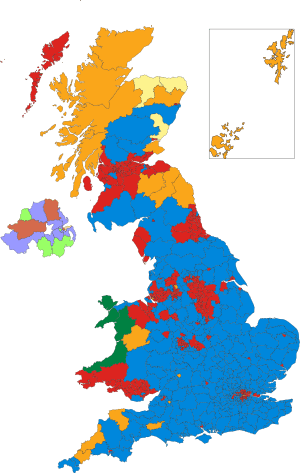

Colours denote the winning party, as shown in the main table of results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Composition of the House of Commons after the election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Major had won the Conservative Party leadership election in November 1990 following the resignation of Margaret Thatcher. During his first term leading up to the 1992 election he oversaw the British involvement in the Gulf War, introduced legislation to replace the unpopular Community Charge with Council Tax, and signed the Maastricht Treaty. The economy was facing a recession around the time of Major's appointment, along with most of the other industrialised nations. Because it confounded the opinion polls, the 1992 election was one of the most dramatic elections in the UK since the end of the Second World War.[1]

The BBC's live television broadcast of the election results was presented by David Dimbleby, Peter Snow, Tony King and John Cole.[2] On ITV, the ITN-produced coverage was presented by Jon Snow, Alastair Stewart, and Julia Somerville, with Sir Robin Day performing the same interviewing role for ITV as he had done for the BBC on many previous election nights. Sky News presented full coverage of a general election night for the first time. Their coverage was presented by David Frost, Michael Wilson, Selina Scott, Adam Boulton and political scientist Michael Thrasher, with former BBC political journalist Donald MacCormick presenting analysis of the Scottish vote.

The Conservative Party received what remains the largest number of votes in a general election in British history, breaking the previous record set by Labour in 1951.[3] Former Conservative Leader and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Former Labour Party Leader Michael Foot, former SDP Leader David Owen, two former Chancellor of the Exchequer's Geoffrey Howe and Denis Healey, former Home Secretary Merlyn Rees, Francis Maude, Norman Tebbit, Rosie Barnes, Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams and Speaker of the House of Commons Bernard Weatherill left the House of Commons as a result of this election, though Maude and Adams returned at the next election.

Overview

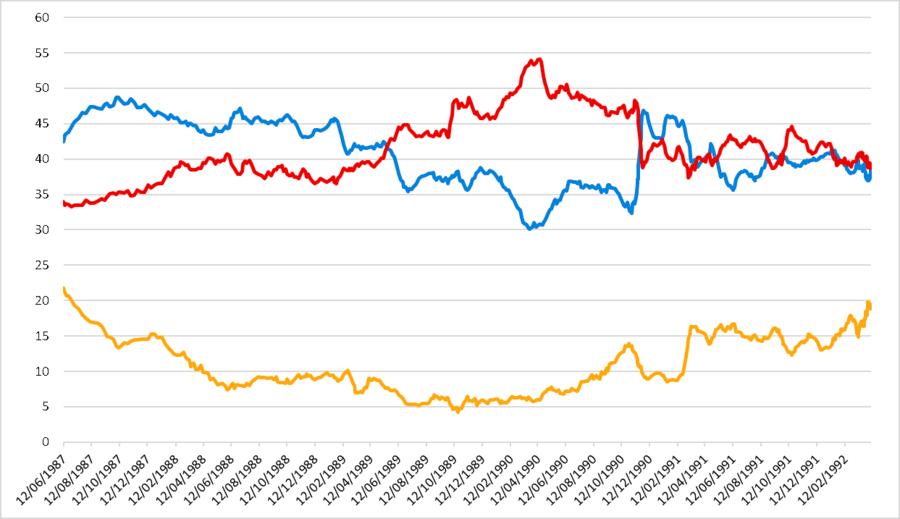

The Conservatives had been elected by a landslide in the 1987 general election under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher, but her popularity had sharply declined in 1989–90 due to the early 1990s recession, internal divisions in the party and the unpopular Community Charge (also known as the 'poll tax'). Labour began to lead the Conservatives in the opinion polls by as much as 20 percentage points. Thatcher resigned after the party leadership ballot in November 1990 and was replaced by John Major. This was well received by the public; Labour lost some momentum as it reduced the impact of their calls for "Time for a Change".[4]

1991 was an eventful year for the Government. Only seven weeks after taking office, Operation Desert Storm of the Gulf War saw the Major government's first foreign affairs crisis, and the successful outcome led to a boost in opinion polls for Major. He also announced that the unpopular community charge (poll tax) would be replaced with the council tax. However, the deepening recession led to calls from Labour to hold the election in 1991. Major resisted these calls and did not hold the election in 1991.

As 1992 dawned, the recession deepened and the election loomed, most opinion polls suggested that Labour were still favourites to win the election, although the lead in the polls had shifted between Tory and Labour on several occasions since the end of 1990.

Parliament was due to expire no later than 16 June 1992. Major called the election on 11 March, as was widely expected, the day after Chancellor of the Exchequer Norman Lamont had delivered the Budget. The Conservatives maintained strong support in many newspapers, especially The Sun, which ran a series of anti-Labour articles that culminated on election day with a front-page headline which urged "the last person to leave Britain" to "turn out the lights" if Labour won the election.[5]

Campaign

The 50th parliament of the United Kingdom sat last on Monday 16 March, being dissolved on the same day.[6]

Under the leadership of Neil Kinnock the Labour party had undergone further developments and alterations since its 1987 election defeat. Labour entered the campaign confident, with most opinion polls showing a slight Labour lead that if maintained suggested a hung parliament, with no single party having an overall majority.

The parties campaigned on the familiar grounds of taxation and health care. Major became known for delivering his speeches while standing on an upturned soapbox during public meetings. Immigration was also an issue, with Home Secretary Kenneth Baker making a controversial speech stating that, under Labour, the floodgates would be opened for immigrants from developing countries. Some speculated that this was a bid by the Conservatives to shore up its support amongst its white working-class supporters. The Conservatives also pounded the Labour Party over the issue of taxation, producing a memorable poster entitled "Labour's Double-Whammy", showing a boxer wearing gloves marked "tax rises" and "inflation".

An early setback for Labour came in the form of the "War of Jennifer's Ear" controversy, which questioned the truthfulness of a Labour party election broadcast concerning National Health Service (NHS) waiting lists.

Labour seemingly recovered from the NHS controversy, and opinion polls on 1 April (dubbed "Red Wednesday") showed a clear Labour lead. But the lead fell considerably in the following day's polls. Observers blamed the decline on the Labour Party's triumphalist "Sheffield Rally", an enthusiastic American-style political convention at the Sheffield Arena, where Neil Kinnock famously cried out "We're all right!" three times.[7] However some analysts and participants in the campaign believed it actually had little effect, with the event only receiving widespread attention after the election.[8]

This was the first general election for the newly formed Liberal Democrats, a party formed by the formal merger of the SDP-Liberal Alliance. Its formation had not been without its problems, but under the strong leadership of Paddy Ashdown, who proved to be a likeable and candid figure, the party went into the election ready. They focused on education throughout the campaign, as well as a promise on reforming the voting system.[9]

The weather was largely dull for most of the campaign but sunny conditions on 9 April may have been a factor in the high turnout.[10][11][12]

Minor parties

In Scotland the Scottish National Party (SNP) hoped for a major electoral breakthrough in 1992 and had run a hard independence campaign with "Free by '93" as their slogan. Although the party increased its total vote by 50% compared to 1987, they only held onto the three seats they had won at the previous election. They lost Glasgow Govan, which their deputy leader Jim Sillars had taken in a by-election in 1988. Sillars quit active politics after the general election with a parting shot at the Scottish electorate as being "ninety-minute patriots", referring to their supporting the Scotland national football team only during match time.[13]

The election also saw a small change in Northern Ireland: the Conservatives organised and stood candidates in the constituent country for the first time since the Ulster Unionist Party had broken with them in 1972 over the Sunningdale Agreement. Although they won no seats, their best result was Laurence Kennedy achieving over 14,000 votes to run second to James Kilfedder in North Down.

Retirees

Margaret Thatcher, Norman Tebbit, Denis Healey, Nigel Lawson, Geoffrey Howe, Michael Foot, David Owen, Merlyn Rees, then-Speaker Bernard Weatherill, Cecil Parkinson, John Wakeham, Nicholas Ridley and Peter Morrison were among the prominent retirees. Alan Clark also retired from Parliament, though he returned in 1997 as MP for Kensington and Chelsea.

Endorsements

The following newspapers endorsed political parties running in the election in the following ways:[14]

| Newspaper | Party/ies endorsed | Circulation (in millions) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Sun | Conservative Party | 3.6 | |

| Daily Mirror | Labour Party | 2.9 | |

| Daily Mail | Conservative Party | 1.7 | |

| Daily Express | Conservative Party | 1.5 | |

| Daily Telegraph | Conservative Party | 1.0 | |

| The Guardian | Labour Party | 0.4 | |

| Liberal Democrats | |||

| The Independent | None | 0.4 | |

| The Times | Conservative Party | 0.4 | |

In a move later described in The Observer as appalling to its City readership,[15] the Financial Times endorsed the Labour Party in this general election.

Polling

Almost every poll leading up to polling day predicted either a hung parliament with Labour the largest party, or a small Labour majority of around 19 to 23. Polls on the last few days before the country voted predicted a very slim Labour majority.[16] Of the 50 opinion polls published during the election campaign period, 38 suggested Labour had a narrow but clear lead.[17] After the polls closed, the BBC and ITV exit polls still predicted that there would be a hung parliament and "that the Conservatives would only just get more seats than Labour".[18]

With opinion polls at the end of the campaign showing Labour and the Conservatives neck and neck, the actual election result was a surprise to many in the media and in polling organisations. The apparent failure of the opinion polls to come close to predicting the actual result led to an inquiry by the Market Research Society, and would eventually result in the creation of the British Polling Council a decade later. Following the election, most opinion polling companies changed their methodology in the belief that a 'Shy Tory Factor' affected the polling.

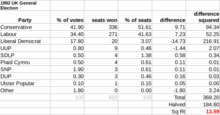

Results

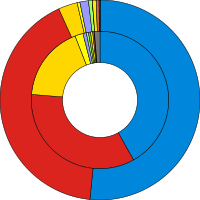

The election turnout of 77.67%[19] was the highest in 18 years. There was an overall Labour swing of 2.2%, which widened the gap between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. Although the percentage of Conservative votes was only 0.3% down on 1987, the Conservative overall majority in the House of Commons was reduced from 102 to 21. This number was reduced progressively during the course of Major's term in office due to defections of MPs to other parties, by-election defeats, and for a time in 1994–95 the suspension of the Conservative whip for some MPs who voted against the government on its European policy—by 1996, the Conservative majority had been reduced to just 1 seat, and they were in a minority going into 1997 until the 1997 general election. The Conservatives in 1992 received 14,093,007 votes,[19] the highest total of votes for any political party in any UK general election, beating the previous largest total vote of 13.98 million achieved by Labour in 1951 (although this was from a smaller electorate and represented a higher vote share). Nine government ministers lost their seats in 1992, including party chairman Chris Patten.

The Sun's analysis of the election results was headlined "It's the Sun wot won it", though in his testimony to the April 2012 Leveson inquiry, Rupert Murdoch claimed that the "infamous" headline was "both tasteless and wrong".[20] Tony Blair also accepted this theory of Labour's defeat and put considerable effort into securing The Sun's support for New Labour, both as Leader of the Opposition before the 1997 general election and as Prime Minister afterwards.

This election continued the Conservatives' decline in Northern England, with Labour regaining many seats they had not held since 1979. The Conservatives also began to lose support in the Midlands, but achieved a slight increase in their vote in Scotland, where they had a net gain of one seat. Labour and Plaid Cymru strengthened in Wales, with Conservative support declining. However, in the South East, South West, London and Eastern England the Conservative vote held up, leading to few losses there: many considered Basildon to be indicative of a nouveau riche working-class element, referred to as Essex Man, voting strongly Conservative. This election is the most recent in which the Conservatives won more seats than Labour in Greater London, at 48 to 35;[19] in the 1997 election, the Conservatives would win only 11.[21]

For the Liberal Democrats their first election campaign was a reasonable success; the party had worked itself up from a "low base" during its troubled creation and come out relatively unscathed.[22]

It was Labour's second general election defeat under leader Neil Kinnock and deputy leader Roy Hattersley. Both resigned soon after the election, and were succeeded by John Smith and Margaret Beckett respectively.

Sitting MPs Dave Nellist, Terry Fields, Ron Brown, John Hughes and Syd Bidwell, who had been expelled or deselected by the Labour Party and stood as independents, were all defeated, although in Nellist's case only very narrowly. Tommy Sheridan, fighting the election from prison, polled 19%.

| 336 | 271 | 20 | 24 |

| Conservative | Labour | LD | Oth |

| Candidates | Votes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Leader | Stood | Elected | Gained | Unseated | Net | % of total | % | No. | Net % | |

| Conservative | John Major | 645 | 336 | 3 | 44 | −41 | 51.69 | 41.9 | 14,093,007 | −0.3 | |

| Labour | Neil Kinnock | 634 | 271 | 43 | 1 | +42 | 41.62 | 34.4 | 11,560,484 | +3.6 | |

| Liberal Democrats | Paddy Ashdown | 632 | 20 | 4 | 6 | −2 | 3.07 | 17.8 | 5,999,606 | −4.8 | |

| SNP | Alex Salmond | 72 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.46 | 1.9 | 629,564 | +0.6 | |

| UUP | James Molyneaux | 13 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.38 | 0.8 | 271,049 | 0.0 | |

| SDLP | John Hume | 13 | 4 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.61 | 0.5 | 184,445 | 0.0 | |

| Green | Jean Lambert and Richard Lawson | 253 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 170,047 | +0.2 | ||

| Plaid Cymru | Dafydd Wigley | 38 | 4 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.61 | 0.5 | 156,796 | +0.1 | |

| DUP | Ian Paisley | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.46 | 0.3 | 103,039 | 0.0 | |

| Sinn Féin | Gerry Adams | 14 | 0 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0.2 | 78,291 | −0.1 | ||

| Alliance | John Alderdice | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 68,665 | 0.0 | ||

| Liberal | Michael Meadowcroft | 73 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 64,744 | N/A | ||

| Natural Law | Geoffrey Clements | 309 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 62,888 | N/A | ||

| Ind. Social Democrat | N/A | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 28,599 | N/A | ||

| Independent Labour | N/A | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 22,844 | N/A | ||

| UPUP | James Kilfedder | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.15 | 0.1 | 19,305 | 0.0 | |

| Ind. Conservative | N/A | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 11,356 | N/A | ||

| Monster Raving Loony | Screaming Lord Sutch | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 7,929 | +0.1 | ||

| Independent | N/A | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 7,631 | N/A | ||

| BNP | John Tyndall | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 7,631 | N/A | ||

| SDP | John Bates | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 6,649 | N/A | ||

| Scottish Militant Labour | Tommy Sheridan | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 6,287 | N/A | ||

| National Front | John McAuley | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 4,816 | N/A | ||

| True Labour | Sydney Bidwell | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 4,665 | N/A | ||

| Anti-Federalist | Alan Sked | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 4,383 | N/A | ||

| Workers' Party | Marian Donnelly | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 4,359 | 0.0 | ||

| Official Conservative Hove Party | Nigel Furness | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,658 | N/A | ||

| Loony Green | Stuart Hughes | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,538 | N/A | ||

| Independent Unionist | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,256 | N/A | ||

| New Agenda | Proinsias De Rossa | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,133 | N/A | ||

| Independent Progressive Socialist | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,094 | N/A | ||

| Islamic Party | David Pidcock | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,085 | N/A | ||

| Revolutionary Communist | Frank Furedi | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 745 | N/A | ||

| Independent Nationalist | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 649 | N/A | ||

| Communist (PCC) | Jack Conrad | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 603 | N/A | ||

All parties with more than 500 votes shown. Plaid Cymru result includes votes for Green/Plaid Cymru Alliance.

| Government's new majority | 21 |

| Total votes cast[19] | 33,614,074 |

| Turnout | 77.7% |

Incumbents defeated

MPs who lost their seats

Television coverage

The BBC ran coverage from 22:00 till 06:00, and from 09:30 till 16:00 on Friday 10 April.[27][28]

Coverage was, according to the Radio Times, supposed to end at 04:00 on Friday morning, but was extended.[29]

The BBC began construction of the Election 92 studio in October 1990, completing it in February 1991, due to speculation that an early election may be called in 1991. Rehearsals were held in the event of a Conservative and Labour victory.[30]

Although the election was not part of the storyline, there was much background chanting and campaigning in the BBC television soap opera EastEnders.[31]

See also

- List of MPs elected in the 1992 United Kingdom general election

- Baltic Exchange bombing

- 1992 United Kingdom general election in Scotland

- 1992 United Kingdom general election in England

- 1992 United Kingdom general election in Northern Ireland

- 1992 United Kingdom general election in Wales

- 1992 United Kingdom local elections

Manifestos

- The Best Future For Britain – 1992 Conservative manifesto.

- It's time to get Britain working again – 1992 Labour Party manifesto.

- Changing Britain for good – 1992 Liberal Democrats manifesto.

Notes

- As SDP-Liberal Alliance.

- "1992: Tories win again against odds". BBC News. 5 April 2005. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- "BBC Election '92". YouTube.

- "Election Statistics: UK 1918–2017". House of Commons Library. 23 April 2017. p. 12. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- "Poll tracker: Interactive guide to the opinion polls". BBC News. 29 September 2009.

- Douglas, Torin (14 September 2004). "Forty years of The Sun". BBC News. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- "Charities Bill [H.L.] (Hansard, 16 March 1992)". hansard.millbanksystems.com.

- "UK General Election 1992 – Neil "We're Alright" Kinnock at the 1992 Sheffield Rally". YouTube. 30 October 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Westlake, Martin (2001). Kinnock: The Biography (3rd ed.). London: Little, Brown Book Group. pp. 560–564. ISBN 0-3168-4871-9.

- "1992 Personalities". BBC News. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/binaries/content/assets/mohippo/pdf/o/4/mar1992.pdf

- https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/binaries/content/assets/mohippo/pdf/o/7/apr1992.pdf

- ratpackmanreturns (28 December 2007). "BBC1 Election Day 1992 coverage" – via YouTube.

- Peterkin, Tom (28 April 2003). "Swinney should stop his sneering at 'second best'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- 'Newspaper support in UK general elections' (2010) on The Guardian

- Robinson, James (30 March 2008). "FT's ebullient leader revels in the power of newsprint". The Observer. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "How did Labour lose in '92?: The most authoritative study of the last general election is published tomorrow. Here, its authors present their conclusions and explode the myths about the greatest upset since 1945". The Independent. 29 May 1994. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Cowling, David (18 February 2015). "How political polling shapes public opinion". BBC News. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Firth, D., Exit polling explained, University of Warwick, Statistics Department.

- "General Election Results 9 April 1992" (PDF). parliament.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- Dowell, Ben (25 April 2012). "Rupert Murdoch: 'Sun wot won it' headline was tasteless and wrong". The Guardian. London: Guardian Newspapers. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Rallings, Colin; Thrasher, Michael. "General Election Results, 1 May 1997" (PDF). UK Parliament Information Office. UK Parliament Information Office. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "1992 Results". BBC News. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Former Labour MP, joined SDP.

- Former Labour MP, joined SNP. Contested sitting MP’s seat.

- Former Labour MP, expelled from party.

- Former Labour MP, de-selected by party.

- Here Is The News (9 April 2017). "BBC: Election 92 (Part 1)" – via YouTube.

- Here Is The News (9 April 2017). "BBC: Election 92 (Part 2)" – via YouTube.

- "BBC One London – 9 April 1992 – BBC Genome". genome.ch.bbc.co.uk.

- https://www.c-span.org/video/?25480-1/british-elections

- https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand/index.php/prog/151DD5F6?bcast=131047530

Further reading

- Butler, David E., et al. The British General Election of 1992 (1992), the standard scholarly study

.jpg)