Portuguese nationality law

Portuguese nationality law is the legal set of rules that regulate access to Portuguese citizenship, which is acquired mainly through descent from a Portuguese parent, naturalisation in Portugal or marriage to a Portuguese citizen.

| Portuguese Citizenship Act | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parliament of Portugal | |

Long title

| |

| Enacted by | Government of Portugal |

| Status: Current legislation | |

In some cases, children born in Portugal to non-citizens may be eligible for Portuguese citizenship. However this does not apply to children born to tourists or short-term visitors. Portuguese citizenship law is complicated by the existence of numerous former colonies and in some cases it is possible to claim Portuguese citizenship by connection with one of these jurisdictions. The most notable of these are Portuguese India (annexed by India in 1961), East Timor and Macau.

Overall the present Portuguese nationality law, dated from 1981, is based on the principle of jus sanguinis, while the previous law of 1959 was based on the principle of jus soli. This shift occurred in 1975 and 1981, thus basically making it difficult to access naturalization not only to first generation migrants, but also to their children and grandchildren. Only very recently, in 2006, was this situation slightly changed, but still stressing jus sanguinis.

In recent years, Portugal created the Golden Visa Program, which provides a way for non-EU residents to gain residency.

Portuguese by origin

Portuguese by origin are:

- The children of a Portuguese mother or father born in Portuguese territory

- The children of a Portuguese mother or father born abroad if the Portuguese parent is there serving the Portuguese State;

- The children of a Portuguese mother or father born abroad if they have their birth registered at the Portuguese civil registry or if they declare that they want to be Portuguese;

- The persons born in Portuguese territory to foreign parents if at least one of the parents was also born in Portugal and resides here, irrespective of title, at the time of birth;

- The persons born in Portuguese territory to foreign parents who are not serving their respective State, if they declare that they want to be Portuguese and provided that one of the parents has legally resided in Portugal for at least two years at the time of the request (There is no age limit for the registration or declaration and it is retroactive to the time of birth. This right is extensive to the next generation only if the previous one completed it before death. No generations can be skipped);

- The persons born in Portuguese territory who do not possess another nationality.

- Persons born abroad with, at least, one Portuguese ascendant in the second degree (grandparent) of the direct line who has not lost this citizenship.

Naturalisation as a Portuguese citizen

A person aged 18 or over may be naturalised as a Portuguese citizen after 5 years legal residence.[1][2] There is a requirement to have sufficient knowledge of the Portuguese language and effective links to the national community. Children aged under 18 may acquire Portuguese citizenship by declaration when a parent is naturalised, and future children of such Portuguese nationals will be considered Portuguese citizens by birth. A naturalised Portuguese citizen only starts to be considered Portuguese once the naturalisation process is done. Therefore, nationality acquired through naturalisation is not transmitted to any possible descendants already adult by the time their parents' naturalisation process is finished.

From 2006 until 2015, a person whose grandparent did not lose Portuguese citizenship was exempt from the residence requirement when applying for naturalisation.[3]

As of 29 July 2015, those born outside Portugal who have at least one grandparent of Portuguese nationality, are granted Portuguese citizenship by extension immediately. The new registration procedure replaces the current provision of Article 6, no. 4—according to which a person who was born abroad and is a 2nd generation descendant of a citizen who has not lost his or her citizenship can acquire Portuguese citizenship by naturalisation, without a residence requirement. The amendment still needs to be signed by the President before entering into law.[4]

Portuguese citizenship by adoption

A child adopted by a Portuguese citizen acquires Portuguese citizenship. The child should be under 18.

Portuguese citizenship by marriage

A person married to a Portuguese citizen for at least 3 years may be able to acquire Portuguese citizenship by declaration. No formal residence period in Portugal is necessary however sufficient knowledge of the Portuguese language and effective ties with the Portuguese community are required.[5]

Jewish Law of Return

An amendment to Portugal's 'Law on Nationality' allows descendants of Portuguese Jews who were expelled in the Portuguese Inquisition to become citizens if they 'belong to a Sephardic community of Portuguese origin with ties to Portugal.'[6]

The Portuguese parliament passed legislation facilitating the naturalization of descendants of 16th-century Jews who fled because of religious persecution. On that day Portugal became the only country besides Israel enforcing a Jewish Law of Return. Two years later, Spain adopted a similar measure.

The motion, which was submitted by the Socialist and Center Right parties, was read on Thursday 11 April 2013 in parliament and approved unanimously on Friday 12 April 2013 as an amendment to Portugal's "Law on Nationality" (Decree-Law n.º 43/2013). Portuguese nationality law was further amended to this effect by Decree-Law n.º 30-A/2015, which came into effect on 1 March 2015.[7]

The amended law allows descendants of Jews who were expelled in the 16th century to become citizens if they "belong to a Sephardic community of Portuguese origin with ties to Portugal," according to José Oulman Carp, president of Lisbon's Jewish community. The website of the World Jewish Congress says that the Jewish Community of Lisbon is the organization that unites local communal groups of Lisbon and its environs, while the Jewish Community of Oporto is the organization that unites local communal groups of Oporto.

Applicants must be able to prove Sephardic surnames in their family tree. Another factor is "the language spoken at home," a reference which also applies to Ladino (Judeo-Portuguese and/or Judeo-Spanish). Furthermore, applicants must be able to prove an "emotional and traditional connection with the former Portuguese Sephardic Community," commonly established through a letter from an orthodox rabbi confirming Jewish heritage.[8] The amendment also says applicants need not reside in Portugal, an exception to the requirement of six years of consecutive residency in Portugal for any applicant for citizenship.

From 2015 several hundred Turkish Jews who were able to prove Sephardi ancestry have immigrated to Portugal and acquired citizenship.[9][10][11] Nearly 1,800 descendants of Sephardic Jews acquired Portuguese nationality in 2017.[12] By February 2018, 12,000 applications were in process, and 1,800 applicants had been granted Portuguese citizenship in 2017.[13] By July 2019 there had been about 33,000 applications, of which about a third had already been granted after a long process of verification.[14]

Dual citizenship

Portugal allows dual citizenship. Hence, Portuguese citizens holding or acquiring a foreign citizenship do not lose Portuguese citizenship. Similarly, those becoming Portuguese citizens do not have to renounce their foreign citizenship.

Citizenship of the European Union

Because Portugal forms part of the European Union, Portuguese citizens are also citizens of the European Union under European Union law and thus enjoy rights of free movement and have the right to vote in elections for the European Parliament.[15] When in a non-EU country where there is no Portuguese embassy, Portuguese citizens have the right to get consular protection from the embassy of any other EU country present in that country.[16][17] Portuguese citizens can live and work in any country within the EU as a result of the right of free movement and residence granted in Article 21 of the EU Treaty.[18]

Former territories of Portugal

Special rules exist concerning the acquisition of Portuguese citizenship through connections with:

- Angola

- Brazil

- Cape Verde

- Portuguese India

- Guinea Bissau

- East Timor

- Macau

- Mozambique

- São Tomé and Príncipe

Portugal enacted Decree-Law 308-A/75 of 24 June 1974 to address the issue of losing or retaining Portuguese citizenship by those who had been born or were living in the Portuguese overseas territories which had gained independence. It was assumed that these persons would acquire the citizenship of the new state. The Decree-Law thus merely stipulated that Portuguese citizenship would be retained by those persons who had not been born overseas but were living there. In addition were those who, despite having been born in the territory of the colonies, had maintained a special connection with mainland Portugal by having been long-term residents there. All those not covered by one of the situations which enabled them to keep Portuguese citizenship would lose it ex lege.

Portuguese India

Formerly known as the Estado da Índia this territory was an integral part of Portugal (as distinct from a colony) under Portugal's Constitution of 1910.

On 19 December 1961 India annexed the territory by military force. The annexation was not recognised by Portugal until 1975, at which time Portugal re-established diplomatic relations with India. The recognition of Indian sovereignty over Portuguese India was backdated to 19 December 1961.

Portuguese nationality law allows those who were Portuguese citizens connected with Portuguese India before 1961 to retain Portuguese nationality. Acquisition of Indian citizenship was determined to be non-voluntary at the time.

One practical obstacle is that the civil records of Portuguese India were abandoned by Portugal during the invasion and hence it can be difficult for descendants of pre-1961 Portuguese citizens from Portuguese India to prove their status.

East Timor

East Timor was a territory of Portugal (Portuguese Timor) until its invasion by Indonesia in 1975, followed by annexation in 1976. Indonesian citizenship was conferred by Indonesia; however, while the Indonesian annexation was recognised by Australia and some other countries, Portugal did not recognise Indonesian sovereignty over East Timor so Decree-Law 308-A/75 of 24 June 1974 was not enforced to revoke the Timorese of their Portuguese nationality.

The question of whether East Timorese were entitled to Portuguese citizenship was raised on numerous occasions in the Australian courts in the context of applications for refugee status in Australia by East Timorese. The Australian immigration authorities argued that if East Timorese were Portuguese citizens, they should be expected to seek protection there and not in Australia.[19][20]

East Timor became an independent nation on 20 May 2002. However, owing to the lack of employment opportunities in their country and the becoming a member of Community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries, many East Timorese have taken advantage of Portuguese citizenship to live and work in Portugal and other EU countries, such as the UK.[21]

Macau

The former Portuguese territory of Macau became a Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China on 20 December 1999.

Portugal had extended its nationality laws to Macau with those born before 1981 acquiring nationality by jus soli and by jus sanguinis after 1981. Many residents of Macau (either of Chinese & Portuguese descent) hold Portuguese citizenship on this basis. It is no longer possible to acquire Portuguese citizenship by connection with Macau before 3 October 1981 and after 20 December 1999 transfer of sovereignty to China, except by birth or association with the territory previous to that date.[22][23]

However, those born after 20 December 1999 to Portuguese from Macau or Macanese that hold Portuguese citizenship, and/or to Chinese who hold Portuguese citizenship, are eligible to the citizenship themselves due to the Portuguese heritage law[24] (Jus Sanguinis), except when born to Chinese and/or Portuguese parents who possess Chinese citizenship after 20 December 1999 or when Chinese and/or Portuguese couple w/ Portuguese citizenship renounced their nationality by naturalization after 20 December 1999.

Rights and obligations of Portuguese citizens

All Portuguese citizens are:

- able to vote in political elections upon reaching the age of 18.

- able to run for political office.

- able to vote in referendums.

- able to obtain a Portuguese passport.

- prevented from getting deported from Portugal.

As Portuguese citizens are also European citizens, their rights include:

- the right to live, work and retire in any member state of the European Union, for unlimited period.

- the right to vote in local and European elections in other members states.

- the right to stand in local and European elections in other members states.

- the right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other member states when in a non-member state, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state.

More information: Citizenship of the European Union

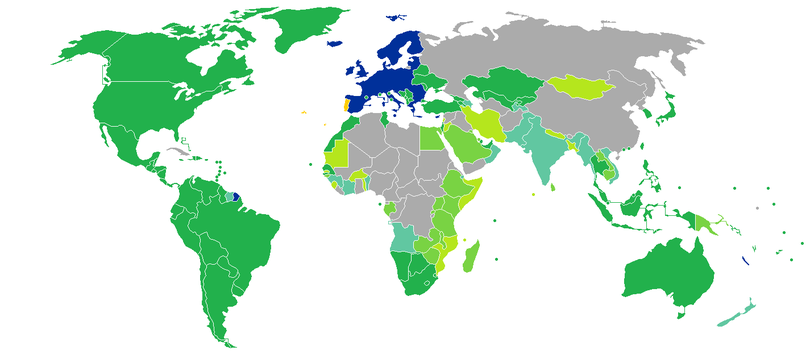

Travel freedom of Portuguese citizens

Visa requirements for Portuguese citizens are administrative entry restrictions by the authorities of other states placed on citizens of Portugal. As of February 2018, Portuguese citizens had visa-free or visa on arrival access to 186 countries and territories, ranking the Portuguese passport 4th in terms of travel freedom (tied with American, Austrian, British, Dutch, Luxembourgian, and Norwegian passports) according to the Henley Passport Index.[25]

The Portuguese nationality is ranked twelfth in Nationality Index (QNI). In addition to external factors including travel freedom, the QNI considers internal factors such as peace and stability, economic strength, and human development.[26]

Recent changes

As of May 2015, under the newly approved Portuguese Nationality Act (Article 1, n.1, paragraph d) persons born abroad with, at least, one Portuguese ascendant in the second degree of the direct line who has not lost this citizenship, are Portuguese by origin, provided that they declare that they want to be Portuguese, that they have effective ties with the national community and, once these requirements are met, that are only required to register their birth in any Portuguese civil registry.[4]

In Portuguese nationality law occurred in 2006[27] based on the proposals of deputy Neves Moreira, member of the Democratic Social Party (PSD). Due to these changes, a foreign-born person whose grandparent never lost Portuguese citizenship is now able to request naturalisation without the need to document 6 years residence in Portugal.[28]

Because nationality acquired through naturalisation is not the same as nationality acquired through descent, members of the PSD proposed in 2009 another change in the law. This proposal would have given nationality by origin (descent) rather than by naturalisation to the grandchildren of Portuguese citizens but it was rejected.[29] In 2013, members of the PSD tried to pass a similar measure again[30] but due to the political and economic crisis that engulfed the country, no vote was ever taken on the measure.[31]

References

- "Portal SEF". Sef.pt. 14 December 2006. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- Archived 10 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "LEI ORGÂNICA N.º 2/2006 – QUARTA ALTERAÇÃO À LEI N.º 37/81, DE 3 DE OUTUBRO (LEI DA NACIONALIDADE)" (PDF). Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "Community: Citizenship granted to grandchildren of Portuguese expats – Portugal – Portuguese American Journal". portuguese-american-journal.com. 29 July 2015. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Changes to the Portuguese nationality regulations" (PDF). PLMJ Law Firm. July 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- 16th century Jewish refugees can claim Portuguese citizenship, Haaretz, 13 April 2013, archived from the original on 24 October 2013

- "Text of Decree-Law n.º 30-A/2015 of Portugal, 27 February 2015" (PDF). cilisboa.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Portuguese Nationality for Sephardic Descendants" (PDF). Comunidade Israelita do Porto. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Olivier DEVOS (16 September 2016). "Amid rising European anti-Semitism, Portugal sees Jewish renaissance". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- Cnaan Liphshiz (12 February 2016). "New citizenship law has Jews flocking to tiny Portugal city". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- "Portugal open to citizenship applications by descendants of Sephardic Jews". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 3 March 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- A soaring number of Jews acquired Portuguese citizenship in 2017

- "1.800 Sephardic Jews get Portuguese citizenship". European Jewish Congress. 26 February 2018.

- Cnaan Liphshiz (17 July 2019). "Portugal grants citizenship to 10,000 descendants of Sephardi Jews". Times of Israel.

- "Portugal". European Union. Archived from the original on 27 June 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Article 20(2)(c) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- Rights abroad: Right to consular protection: a right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other Member States when in a non-EU Member State, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state (Article 23): this is due to the fact that not all member states maintain embassies in every country in the world (14 countries have only one embassy from an EU state). Antigua and Barbuda (UK), Barbados (UK), Belize (UK), Central African Republic (France), Comoros (France), Gambia (UK), Guyana (UK), Liberia (Germany), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (UK), San Marino (Italy), São Tomé and Príncipe (Portugal), Solomon Islands (UK), Timor-Leste (Portugal), Vanuatu (France)

- "Treaty on the Function of the European Union (consolidated version)". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Talks follow migrant worker clash, BBC News, 9 December 2005, retrieved 31 August 2008

- https://web.archive.org/web/20060204072107/http://www.unesco.org.mo/eng/law/11nationality.html. Archived from the original on 4 February 2006. Retrieved 4 February 2006. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "O DIREITO ONLINE – ReflexĂľes sobre a nacionalidade portuguesa em Macau". Odireito.com.mo. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- "Cidadania Portuguesa". Tirarpassaporte.com. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- "Global Ranking – Passport Index 2018" (PDF). Henley & Partners. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "The 41 nationalities with the best quality of life". www.businessinsider.de. 6 February 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "DECRETO N.º 42/X – QUARTA ALTERAÇÃO À LEI N.º 37/81, DE 3 DE OUTUBRO (LEI DA NACIONALIDADE)" (PDF). Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "LEI ORGÂNICA N.º 2/2006 – QUARTA ALTERAÇÃO À LEI N.º 37/81, DE 3 DE OUTUBRO (LEI DA NACIONALIDADE)" (PDF). Article 6.4. Retrieved 1 May 2015.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Projeto de Lei 30/XI". Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "Projeto de Lei 382/XII". Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "How Portugal's politics are spoiling Europe's austerity recipe". 16 July 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

External links

- Portuguese Immigration Office (Serviço de Estangeiros e Fronteiras – SEF)

- Portuguese Citizenship Act (unofficial)

- Portuguese Citizenship Application (in Portuguese)

- Portuguese nationality law (unofficial)

- Decree regulating the Portuguese Nationality Law – August 1982 (in Portuguese)

- (Jewish Communities of Portugal)