Spanish nationality law

Spanish nationality law refers to all the laws of Spain concerning nationality. Article 11 of the First Title of the Spanish Constitution refers to Spanish nationality and establishes that a separate law is to regulate how it is acquired and lost.[1] This separate law is the Spanish Civil Code. In general terms, Spanish nationality is based on the principle of jus sanguinis, although limited provisions exist for the acquisition of Spanish nationality based on the principle of jus soli.

| Spanish Citizenship Act | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Parliament of Spain | |

Long title

| |

| Enacted by | Government of Spain |

| Status: Current legislation | |

History

Spanish nationality law has changed significantly since the 1889 Civil Code provisions on citizenship and nationality, especially during its liberalization during the Second Spanish Republic of 1931 to 1939, the repudiation of the Republican Constitution in 1938, the Francoist constriction of 1954, and the reforms of 1978, 1983, 1990s, and 2000s.[2]

All the constitutions in Spain before 1978 have had an article that defines Spanish nationality, even the constitutions that never came into effect.[3] The current constitution of 1978 is the first that does not define Spanish nationality; rather, article 11 establishes that a separate law is to define and regulate it entirely, namely the Spanish Civil Code.[3] It is also the first constitution that emphasises that those "Spaniards by origin", roughly equivalent to a "natural born Spaniard", cannot be deprived of their nationality.[3] On 13 July 1982, and in accordance to what had been established in the constitution, the first law regarding nationality was approved, which was in fact an amendment to the Spanish Civil Code in effect. This law has been reformed on 17 December 1990, 23 December 1993, 2 November 1995, and most recently 2 October 2002.[4]

The approval of article 11 of the constitution was somewhat controversial, mostly due to the possible confusion it would cause with the term "nationalities", in reference to those communities or regions in Spain with a special historical and cultural identity,[5] a term that had been used in the second article of the constitution.[6] It was suggested that article 11 should substitute the term "nationality" for "citizenship", but it was considered, as it is common in other legislations in Europe and Latin America, that the terms were not synonymous.[3]

Another point of constitutional conflict was that the creation of European Union citizenship gave all nationals of EU member the same basic rights in all member States, including the right of active and passive suffrage in municipal elections. The constitution was reformed to allow this.

Acquisition of Spanish citizenship

Title One of Book One of the Spanish Civil Code lays out the details of Spanish nationality.[7][4]

Jus sanguinis

Spanish legislation regarding nationality establishes two types of nationality: "Spanish nationality by origin" (nacionalidad española de origen, in Spanish)—that is, a "natural-born Spaniard"—and the "Spanish nationality not by origin" (nacionalidad española no de origen, in Spanish).

According to article 17 of the Spanish Civil Code, Spaniards by origin are:[7][4][8]

- those individuals born of a Spanish parent;

- those individuals born in Spain of foreign parents if at least one of the parents was also born in Spain, with the exception of children of foreign diplomatic or consular officers accredited in Spain;

- those individuals born in Spain of foreign parents if neither of them has a nationality, or if the legislation of either parent's home country does not grant the child any nationality;

- those individuals born in Spain of undetermined filiation; those individuals whose first known territory of residence is Spain, are considered born in Spain.

Foreign minors under the age of 18 acquire Spanish nationality by origin upon being adopted by a Spanish national.[9] If the adoptee is 18 years or older, he or she can apply for Spanish nationality by origin within two years after the adoption took place.[9][4]

At points since the 1889 Civil Code, various regulations have been in effect requiring registration of births of Spaniards abroad and limiting citizenship by descent to a number of generations that has been in flux.[2] These rules have changed over time, which requires historical analysis to determine which rights may apply.[2]

Under Article 24.1, persons born outside Spain, other than in specified Iberophone countries, to a Spanish citizen born in Spain will lose Spanish nationality if they exclusively use a foreign nationality acquired before adulthood. That loss can be avoided by registering the desire to preserve Spanish nationality in the civil registry at a Spanish consulate.[4]

Until an 8 October 2002 change in the law, persons born outside Spain in an Ibero-American country or specific former Spanish territories to a Spanish citizen parent born outside Spain, and who acquired that other country's citizenship, were Spanish citizens with no retention requirements.[10] After that date, second generation abroad Spaniards from the Iberosphere who were not already 18 or in legal majority (adulthood) by that date, and who acquired the other country's citizenship, were subject to a requirement to conserve or retain their Spanish nationality by declaration through Spanish authorities within three years of majority, a period typically ending at age 21.[10]

The range of Ibero-American countries in which Spanish jus sanguinis will apply to a person of Spanish descent has also changed over time as Spain has entered into agreements and treaties with countries.[2]

All other individuals that acquire Spanish nationality, other than by which is specified above, are "Spaniards not by origin".

By option

Article 20 of the Spanish Civil Code, established that the following individuals have the right to apply (lit. "to opt") for Spanish nationality:[7][4][8]

- those individuals that were under the tutelage of a Spanish citizen,

- those individuals whose father or mother had been originally Spanish and born in Spain (i.e. those individuals who were born after their parent(s) had lost Spanish nationality, or those born with another nationality before 1982 to a Spanish mother[11]).

- those individuals mentioned in the second bullet-point in article 17, and adopted foreigners of 18 years of age or more.

Spanish nationality by option must be claimed within two years after their 18th birthday or after their "emancipation", regardless of age, except for those individuals whose father or mother had been originally Spanish and born in Spain, for which there is no age limit.[12] Spanish nationality by option does not confer "nationality by origin" unless otherwise specified (i.e. those mentioned in article 17, and those who obtained it through the Law of Historical Memory).

Naturalization

Spanish nationality can be acquired by naturalisation, which is given only at the discretion of the government through a Royal Decree, and under exceptional circumstances, for example to notable individuals.[7][4][8]

Any individual can also request Spanish nationality after a period of continuous legal residence, as long as he or she is 18 years or older, or through a legal representative if he or she is younger.[7][4][13] Under Article 22, to apply for nationality through residence it is necessary for the individual to have lived in Spain for:[7][8]

- ten years, or

- five years if the individual is a refugee, or

- two years if the individual is a citizen of a country of Ibero-America (including Portugal), Andorra, the Philippines, Equatorial Guinea, or if the individual can prove they are a Sephardi Jew with a connection to Spain; or

- one year for individuals:

- born in Spanish territory, or

- who did not exercise their right to their nationality by option within the established period of time, or

- who have been under the legal tutelage or protection of a Spanish citizen or institution for two consecutive years,

- who have been married for one year to a Spanish national and are not separated legally or de facto, or

- are widow(er)s of a Spanish national if at the time of death they were not legally or de facto separated, or

- who were born outside of Spain, if one of their parents or grandparents was originally Spanish (i.e. Spanish by origin).

Sephardi Jews

In 2015 the Government of Spain passed Law 12/2015 of 24 June, whereby Sephardi Jews with a connection to Spain could obtain Spanish nationality by naturalisation, without the residency requirement as explained above. The law required applicants to apply within three years from 1 October 2015, provide evidence of their Sephardi origin and some connection with Spain, and pass examinations on the Spanish language and Spanish culture.[14] The law provided for a possible one-year extension of the deadline to 1 October 2019; it was indeed extended in March 2018.[15] This path to citizenship is in restitution for the 1492 expulsion of the Jews from Spain.

The Law establishes the right to Spanish nationality of Sephardi Jews with a connection to Spain.[16] An Instruction of 29 September 2015 removes a provision whereby those acquiring Spanish nationality by law 12/2015 must renounce any other nationality held.[17] Most applicants must pass tests of knowledge of the Spanish language and Spanish culture, but those who are under 18, or handicapped, are exempted. A Resolution in May 2017 also exempted those aged over 70.[18]

By July 2017 the government of Spain had registered about 4,300 applications who had begun the proceedings. 1,000 had signed before a notary and filed officially. A hundred, from various countries, had been granted citizenship, with another 400 expected within weeks. The Spanish government was taking 8–10 months to decide on each case.[19] By March 2018 over 6,200 people had been granted Spanish citizenship under this law.[15] Applicants must pass a cultural and historical knowledge exam called the CCSE (Conocimientos Constitucionales y Socioculturales de España) and a language test called the DELE (Diploma de Español como Lengua Extranjera -Certificate of Spanish as a Foreign Language-).

Loss and recovery of Spanish nationality

Spanish nationality can be lost under the following circumstances:[4][8][7]

- Those individuals of 18 years of age or more whose residence is not Spain and who acquire voluntarily another nationality, or who use exclusively another nationality which was conferred to them prior to their age of emancipation lose Spanish nationality. In this case, loss of nationality occurs three years after the acquisition of the foreign nationality or emancipation only if the individual does not declare their will to retain Spanish nationality. The exception to this are those Spaniards by origin who acquire the nationality of an Iberoamerican country, Andorra, Philippines, Equatorial Guinea or Portugal;

- Those Spanish nationals that expressly renounce Spanish nationality if they also possess another nationality and reside outside Spain will lose Spanish nationality;

- Those minors born outside Spain that have acquired Spanish citizenship being children of Spanish nationals that were also born outside Spain, and if the laws of the country in which they live grant them another nationality, will lose Spanish nationality if they do not declare their will to retain it within three years after their 18th birthday or the date of their emancipation.

The Civil Code regulations on loss of citizenship, and the reasons for it—including lack of registration with Spanish consular authorities overseas—and the practical application of those regulations, has varied over time.[2]

Spanish nationality is not lost as described above if Spain is at war.

In addition, Spaniards "not by origin", will lose their nationality if:[7][4][8]

- they use exclusively for a period of three years their previous nationality—with the exception of the nationality of those countries with which Spain has signed an agreement of dual nationality;

- they participate voluntarily in the army of a foreign country, or serve in public office in a foreign government, against the specific prohibition of the Spanish Government;

- they had lied or committed fraud when they applied for Spanish nationality.

People who lose Spanish nationality can recover it if they become legal residents in Spain.[8][4] Emigrants and their children are not required to return to Spain to recover their Spanish nationality. (Since the nationality law automatically grants Spanish nationality to people born of a Spanish parent, a person born outside Spain to a parent of Spanish birth and nationality who uses the citizenship of the other country exclusively since birth is said to "recover" their Spanish nationality should they apply for it).

Spanish nationality by the Law of Historical Memory

In 2007, the Congress of Deputies, under the government of prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, approved the Law of Historical Memory with the aim of recognising the rights of those who suffered persecution or violence during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), and the dictatorial regime that followed (1939-1975). In recognition of the "injustice produced by the exile" of thousands of Spaniards, the law allowed their descendants to obtain Spanish nationality by origin, specifically for:[20][21]

- those individuals born of a parent that was Spanish by origin, regardless of the place of birth of the parent, whatever the age of the applicant. (The Spanish Civil code currently grants Spanish nationality "by origin" only to those individuals born of a Spanish national who was born in Spain, and Spanish nationality "not by origin" to those individuals born of a Spanish national who was not born in Spain only if they apply for it prior to the second year after their 18th birthday or emancipation); and

- those individuals whose grandfather or grandmother had been exiled because of the Spanish Civil War, and had lost his or her Spanish nationality. In this case the applicant must have proven that the grandparent had left Spain as a refugee or that the grandparent left Spain between 18 July 1936 and 31 December 1955.

The law also granted Spanish nationality by origin to those foreign individual members of the International Brigades who had defended the Second Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War. (In 1996, they were granted Spanish nationality "not by origin", which implied that they had to renounce their previous nationality—Spanish nationals "by origin" cannot be deprived of their nationality, and therefore, these individuals can also retain their original nationality).

By virtue of this law, if an individual, whose father or mother had been originally Spanish and born in Spain, and who had previously acquired Spanish nationality "not by origin" by option (art. 20) could request his or her nationality be changed to nationality "by origin", if he or she chose to do so.[20]

The period wherein the Spanish nationality could be acquired by the Law of Historical memory started on 27 December 2008, and was concluded on 26 December 2011. Even though the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has not yet released the final count, and it is still reviewing applications, 446,277 individuals had applied for Spanish nationality through this law by 30 November 2011. Around 95% were Latin American, half of them from Cuba and Argentina.[22] To the surprise of government officials, 92.5% of all applications were made by sons or daughters of Spaniards by origin regardless of their place of birth, and only 6.1% by grandchildren of refugees.[22] More than five centuries after Jews were banished from the kingdom of Spain during the Spanish Inquisition, Spanish lawmakers approved, on 10 June 2015, a law allowing descendants of Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain in 1492 to seek Spanish nationality without giving up their current citizenship.

Many applications under the law came from Cuba, which also offered those Cubans an ability to leave the island, and to also live and work in EU countries other than Spain.[23][2]

The measure, championed by the centre-right government of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, grants dual citizenship rights for Sephardic Jews, those descended from Jews expelled from Spain in 1492.

Dual citizenship

Dual citizenship is permitted for all Spaniards by origin, as long as they declare their will to retain Spanish nationality within three years of the acquisition of another nationality. This requirement is waived for the acquisition of the nationality of an Iberoamerican country, Andorra, the Philippines, Equatorial Guinea or Portugal, and any other country that Spain may sign a bilateral agreement with.[1][24]

Foreign nationals who acquire Spanish nationality must renounce their previous nationality, unless they are natural-born citizens of an Iberoamerican country, Andorra, the Philippines or Equatorial Guinea.[1][24]

Since October 2002, dual citizens of Spain and another country who are born outside Spain to a Spanish citizen parent born outside Spain must declare to conserve their Spanish nationality between ages 18 and 21.[4][10]

Citizenship of the European Union

Because Spain forms part of the European Union, Spanish citizens are also citizens of the European Union under European Union law and thus enjoy rights of free movement and have the right to vote in elections for the European Parliament.[25] When in a non-EU country where there is no Spanish embassy, Spanish citizens have the right to get consular protection from the embassy of any other EU country present in that country.[26][27] Spanish citizens can live and work in any country within the EU as a result of the right of free movement and residence granted in Article 21 of the EU Treaty.[28]

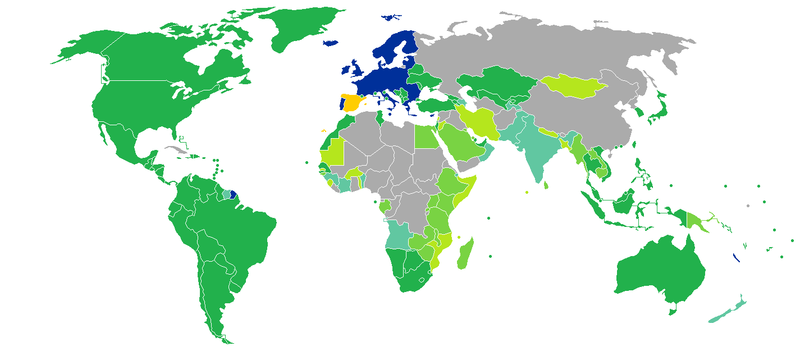

Travel freedom of Spanish citizens

According to the 2020 Visa Restrictions Index, holders of a Spanish passport can visit 188 countries visa-free or with visa on arrival. In the index, Spain is in the 4th rank in terms of travel freedom.

The Spanish nationality is ranked eleventh in Nationality Index (QNI). This index differs from the Visa Restrictions Index, which focuses on external factors including travel freedom. The QNI considers, in addition, to travel freedom on internal factors such as peace & stability, economic strength, and human development as well.[29]

References

- "Título I. De los derechos y deberes fundamentales - Constitución Española". Web.archive.org. 5 April 2010. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Marín, Ruth Rubio; Sobrino, Irene; Pérez, Alberto Martín; Moreno Fuentes, Francisco Javier (January 2015). "Country Report on Citizenship Law: Spain" (PDF). European University Institute. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Archived 7 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Government of Spain (2018). "Código Civil". Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Nacionalidad. Real Academia Española.

- The second article reads: The Constitution is based on the indissoluble unity of the Spanish Nation, the common and indivisible homeland of all Spaniards; it recognises and guarantees the right to self-government of the nationalities and regions of which it is composed and the solidarity among them all.

- Spanish Ministry of Justice (2013). Clausen, Sofia de Ramon Luca (ed.). "Spanish Civil Code" (PDF). Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Real Decreto de 24 de julio de 1889, texto de la edición del Código Civil mandada publicar en cumplimento de la Ley de 26 de mayo último. TÍTULO PRIMERO. De los españoles y extranjeros (Vigente hasta el 15 de Julio de 2015)". Noticias.juridicas.com. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "Real Decreto de 24 de julio de 1889, texto de la edición del Código Civil mandada publicar en cumplimento de la Ley de 26 de mayo último (Vigente hasta el 23 de Julio de 2011)". Noticias.juridicas.com. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Government of Spain. "Ley 36/2002, de 8 de octubre, de modificación del Código Civil en materia de nacionalidad". Second supplementary provision. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Spain: Information on whether a person born of a Spanish mother outside Spain is automatically considered a Spanish national". Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Adquisición de la nacionalidad española por opción". Consulado General de España en SÃO PAULO. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Carta de naturaleza - ¿Cómo se adquiere la nacionalidad española? - Ministerio de Justicia". Mjusticia.gob.es. 22 January 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Rhodes Jewish Museum: Frequently asked questions for Spanish citizenship for Sephardi Jews. Date (embedded in the PDF): 3 September 2015

- Juan José Mateo (5 March 2018). "El Gobierno amplía hasta 2019 el plazo para que los sefardíes obtengan la nacionalidad" [Government extends until 2019 the deadline for Sefardis to gain nationality]. El País (in Spanish).

- Ley 12/2015, de 24 de junio, en materia de concesión de la nacionalidad española a los sefardíes originarios de España (Law 12/2015, of 24 June, regarding acquisition of Spanish nationality by Sephardis with Spanish origins) (in Spanish)

- Instrucción de 29 de septiembre de 2015, de la Dirección General de los Registros y del Notariado, sobre (…) concesión de la nacionalidad española a los sefardíes originarios de España (Instruction of 29 September 2015, from the Directorate General of Registration and Notaries, on the application of law 12/2015, regarding acquisition of Spanish nationality by Sephardis with Spanish origins (in Spanish)

- Resolución del Director General de los Registros y del Notariado (…) sobre dispensa pruebas a mayores de 70 años (Resolution of the Directorate General of Registration and Notaries, of the questions raised by the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain and the Council General of Notaries on exempting over-70s from tests) (in Spanish)

- Lusi Portero (7 February 2017). "Spanish Citizenship for Sephardic Jews". Rhodes Jewish Museum. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Archived December 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived December 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Rebossio, Alejandro (2 January 2012). "Unos 446.000 descendientes de españoles han solicitado la nacionalidad". El País. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Mateos, Pablo. "External and Multiple Citizenship in the European Union. Are 'Extrazenship' Practices Challenging Migrant Integration Policies?". Princeton University. pp. 21–23. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Tener la doble nacionalidad - Ministerio de Justicia". Mjusticia.gob.es. 23 January 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "Spain". European Union. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Article 20(2)(c) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- Rights abroad: Right to consular protection: a right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other Member States when in a non-EU Member State, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state (Article 23): this is due to the fact that not all member states maintain embassies in every country in the world (14 countries have only one embassy from an EU state). Antigua and Barbuda (UK), Barbados (UK), Belize (UK), Central African Republic (France), Comoros (France), Gambia (UK), Guyana (UK), Liberia (Germany), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (UK), San Marino (Italy), São Tomé and Príncipe (Portugal), Solomon Islands (UK), Timor-Leste (Portugal), Vanuatu (France)

- "Treaty on the Function of the European Union (consolidated version)" (PDF). Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "The 41 nationalities with the best quality of life". www.businessinsider.de. 6 February 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2018.