Irish nationality law

Irish nationality law is contained in the provisions of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004 and in the relevant provisions of the Irish Constitution. A person may be an Irish citizen[1] through birth, descent, marriage to an Irish citizen or through naturalisation. The law grants citizenship to individuals born in Northern Ireland under the same conditions as those born in the Republic of Ireland.

| Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956-2004 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Oireachtas | |

Long title

| |

| Enacted by | Government of Ireland |

| Status: Current legislation | |

History

Irish Free State Constitution (1922)

Irish citizenship law originates with Article 3 of the Constitution of the Irish Free State which came into force on 6 December 1922; it applied domestically only until the enactment of the Constitution (Amendment No. 26) Act 1935 on 5 April 1935.[2][3] Any person domiciled in the island of Ireland on 6 December 1922 was an Irish citizen if:

- he or she was born in the island of Ireland;

- at least one of his or her parents was born in the island of Ireland; or

- he or she had been ordinarily resident in the island of Ireland for at least seven years;

except that "any such person being a citizen of another State" could "[choose] not to accept" Irish citizenship. (The Article also stated that "the conditions governing the future acquisition and termination of citizenship in the Irish Free State […] shall be determined by law".)

While the Constitution referred to those domiciled "in the area of the jurisdiction of the Irish Free State", this was interpreted as meaning the entire island. This was because under the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, Northern Ireland had the right to opt out of the Irish Free State within one month of the Irish Free State coming into existence.[4] On 7 December 1922, the day after the Irish Free State was created, Northern Ireland exercised this option.[4] However the ‘twenty-four-hour gap’ meant that every person who was ordinarily resident in Northern Ireland on 6 December 1922 was deemed to be an Irish citizen under Article 3 of the Constitution.[4][5]

The status of the Irish Free State as a Dominion within the British Commonwealth was seen by the British authorities as meaning that a "citizen of the Irish Free State" was merely a member of the wider category of "British subject"; this interpretation could be supported by the wording of Article 3 of the Constitution, which stated that the privileges and obligations of Irish citizenship applied "within the limits of the jurisdiction of the Irish Free State". However, the Irish authorities repeatedly rejected the idea that its citizens had the additional status of "British subject".[6] Also, while the Oath of Allegiance for members of the Oireachtas, as set out in Article 17 of the Constitution, and as required by Art. 4 of the Treaty, referred to "the common citizenship of Ireland with Great Britain", a 1929 memorandum on nationality and citizenship prepared by the Department of Justice at the request of the Department of External Affairs for the Conference on the Operation of Dominion Legislation stated:

The reference to 'common citizenship' in the Oath means little or nothing. 'Citizenship' is not a term of English law at all. There is not, in fact, 'common citizenship' throughout the British Commonwealth: the Indian 'citizen' is treated by the Australian 'citizen' as an undesirable alien.[7]

Irish passports were issued from 1923, and to the general public from 1924, but the British government objected to them, and their wording for many years. Using an Irish Free State passport abroad, if consular assistance from a British Embassy was required, could lead to administrative difficulties.

Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1935

The 1922 Constitution provided for citizenship for only those alive on 6 December 1922. No provision was made for those born after this date. As such it was a temporary provision which required the enactment of a fully-fledged citizenship law which was done by the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1935. This Act provided for, among other things:

- Irish citizenship by birth for anyone born within the Irish Free State on or after 6 December 1922;

- Irish citizenship by descent for anyone born outside the Irish Free State on or after 6 December 1922, and before the passing of the 1935 Act (10 April 1935) and whose father was, on the day of such person's birth, an Irish citizen;

- Irish citizenship by descent for anyone born outside the Irish Free State on or after the passing of the 1935 Act (10 April 1935) and whose father was an Irish citizen at the time of his or her birth. If the father had been born outside the Irish Free State, such birth had to be registered in register of Northern-Ireland- or foreign births. "A registration requirement was imposed for those born on or after the passing of the Act (10 April 1935) outside the Irish Free State of a father himself born outside the Irish Free State (including in Northern Ireland) or a naturalised citizen.";[8]

- a naturalisation procedure; and

- automatic denaturalisation for anyone who became a citizen of another country on or after reaching 21 years of age.

The provision of citizenship by descent had the effect, given the interpretation noted above, of providing citizenship for those in Northern Ireland born after 6 December 1922 so long as their father had been resident anywhere in Ireland on said date. However, this automatic entitlement was limited to the first generation, with the citizenship of subsequent generations requiring registration and the surrendering of any other citizenship held at the age of 21. The combination of the principles of birth and descent in the Act respected the state's territorial boundary, with residents of Northern Ireland treated "in an identical manner to persons of Irish birth or descent who resided in Britain or a foreign country".[9] According to Brian Ó Caoindealbháin, the 1935 Act was, therefore, compatible with the state's existing borders, respecting and, in effect, reinforcing them.[10]

The Act also provided for the establishment of the Foreign Births Register.

Further, the 1935 Act was an attempt to assert the sovereignty of the Free State and the distinct nature of Irish citizenship, and to end the ambiguity over the relations between Irish citizenship and British subject status. Nonetheless, London continued to recognise Irish citizens as British subjects until the passing of the Ireland Act 1949, which recognised, as a distinct class of persons, "citizens of the Republic of Ireland".[6][11]

Beginning in 1923, some new economic rights were created for Irish citizens. The 1923 Land Act allowed the Irish Land Commission to refuse to allow a purchase of farmland by a non-Irish citizen; during the Anglo-Irish trade war the Control of Manufactures Act 1932 required that at least 50% of the ownership of Irish-registered companies had to be held by Irish citizens. “The 1932 act defined an Irish ‘national’ as a person who had been born within the boundaries of the Irish Free State or had resided in the state for five years before 1932 ... Under the terms of the Control of Manufactures Acts, all residents of Northern Ireland were deemed to be foreigners; indeed, the legislation may have been explicitly designed with this in mind.”[12]

Constitution of Ireland (1937)

The 1937 Constitution of Ireland simply maintained the previous citizenship body, also providing, as the previous constitution had done, that the further acquisition and loss of Irish citizenship was to be regulated by law.

With regard to Northern Ireland, despite the irredentist nature and rhetorical claims of articles 2 and 3 of the new constitution, the compatibility of Irish citizenship law with the state's boundaries remained unaltered.[13]

Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956

In 1956, the Irish parliament enacted the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956. This Act repealed the 1935 Act and remains, although heavily amended, the basis of Irish citizenship law. This act, according to Ó Caoindealbháin, altered radically the treatment of Northern Ireland residents in Irish citizenship law. With the enactment of the Republic of Ireland Act in 1948, and the subsequent passage of the Ireland Act by the British government in 1949, the state's constitutional independence was assured, facilitating the resolution of the unsatisfactory position from an Irish nationalist perspective whereby births in Northern Ireland were assimilated to "foreign" births. The Irish government was explicit in its aim to amend this situation, seeking to extend citizenship as widely as possible to Northern Ireland, as well as to Irish emigrants and their descendants abroad.[14]

The Act therefore provided for Irish citizenship for anyone born in the island of Ireland whether before or after independence. The only limitations to this provision were that anyone born in Northern Ireland was not automatically an Irish citizen but entitled to be an Irish citizen and, that a child of someone entitled to diplomatic immunity in the state would not become an Irish citizen. The Act also provided for open-ended citizenship by descent and for citizenship by registration for the wives (but not husbands) of Irish citizens.

The treatment of Northern Ireland residents in these sections had considerable significance for the state's territorial boundaries, given that their "sensational effect … was to confer, in the eyes of Irish law, citizenship on the vast majority of the Northern Ireland population".[15] The compatibility of this innovation with international law, according to Ó Caoindealbháin was dubious, "given its attempt to regulate the citizenship of an external territory … In seeking to extend jus soli citizenship beyond the state’s jurisdiction, the 1956 Act openly sought to subvert the territorial boundary between North and South". The implications of the Act were readily recognised in Northern Ireland, with Lord Brookeborough tabling a motion in the Parliament of Northern Ireland repudiating “the gratuitous attempt … to inflict unwanted Irish Republican nationality upon the people of Northern Ireland”.[16]

Nevertheless, Irish citizenship continued to be extended to the inhabitants of Northern Ireland for over 40 years, representing, according to Ó Caoindealbháin, "one of the few practical expressions of the Irish state’s irredentism." Ó Caoindealbháin concludes, however, that the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 altered significantly the territorial implications of Irish citizenship law, if somewhat ambiguously, via two key provisions: the renunciation of the constitutional territorial claim over Northern Ireland, and the recognition of "the birthright of all the people of Northern Ireland to identify themselves and be accepted as Irish or British or both, as they may so choose", and that "their right to hold both British and Irish citizenship is accepted by both Governments".

In regard to international law, Ó Caoindealbháin states that, although it is the attempt to confer citizenship extra-territorially without the agreement of the state affected that represents a breach of international law (not the actual extension), the 1956 Act "co-exists uneasily with the terms of the Agreement, and, by extension, the official acceptance by the Irish state of the current border. While the Agreement recognises that Irish citizenship is the birthright of those born in Northern Ireland, it makes clear that its acceptance is a matter of individual choice. In contrast, the 1956 Act continues to extend citizenship automatically in the majority of cases, thereby, in legal effect, conflicting with the agreed status of the border and the principle of consent".[13]

Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1986 and 1994

In 1986, the 1956 Act was amended by the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986. This Act was primarily concerned with removing various gender discriminatory provisions from the 1956 legislation and thus provided for citizenship by registration for the wives and husbands of Irish citizens.

The Act also restricted the open-ended citizenship by descent granted by the 1956 Act by dating the citizenship of third, fourth and subsequent generations of Irish emigrants born abroad, from registration and not from birth. This limited the rights of fourth and subsequent generations to citizenship to those whose parents had been registered before their birth. The Act provided for a six-month transitional period during which the old rules would still apply. Such was the increase in volume of applications for registration from third, fourth and further generation Irish emigrants, the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1994 was enacted to deal with those individuals who applied for registration within the six-month period but who could not be registered in time.

Jus soli and the Constitution

Up until the late 1990s, jus soli, in the Republic, was maintained as a matter of statute law, the only people being constitutionally entitled to citizenship of the Irish state post-1937 were those who had been citizens of the Irish Free State before its dissolution. However, as part of the new constitutional settlement brought about by the Good Friday Agreement, the new Article 2 introduced in 1999 by the Nineteenth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland provided (among other things) that:

It is the entitlement and birthright of every person born in the island of Ireland, which includes its islands and seas, to be part of the Irish nation. That is also the entitlement of all persons otherwise qualified in accordance with law to be citizens of Ireland.

The introduction of this guarantee resulted in the enshrinement of jus soli as a constitutional right for the first time.[17] In contrast the only people entitled to British citizenship as a result of the Belfast Agreement are people born in Northern Ireland to Irish citizens, British citizens and permanent residents.

If immigration was not on the political agenda in 1998, it did not take long to become so afterwards. Indeed, soon after the agreement, the already rising strength of the Irish economy reversed the historic pattern of emigration to one of immigration, a reversal which in turn resulted in a large number of foreign nationals claiming a right to remain in the state based on their Irish-born citizen children.[18] They did so on the basis of a 1989 Supreme Court judgment in Fajujonu v. Minister for Justice where the court prohibited the deportation of the foreign parents of an Irish citizen. In January 2003, the Supreme Court distinguished the earlier decision and ruled that it was constitutional for the Government to deport the parents of children who were Irish citizens.[19] This latter decision would have been thought to put the matter to rest but concerns remained about the propriety of the (albeit indirect) deportation of Irish citizens and what was perceived as the overly generous provisions of Irish nationality law.

In March 2004, the government introduced the draft Bill for the Twenty-seventh Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland to remedy what the Minister for Justice, Michael McDowell, described as an "abuse of citizenship" whereby citizenship was "conferred on persons with no tangible link to the nation or the State whether of parentage, upbringing or of long-term residence in the State".[20] The Amendment did not propose to change the wording of Articles 2 and 3 as introduced by the Nineteenth Amendment, but instead to insert a clause clawing back the power to determine the future acquisition and loss of Irish citizenship by statute, as previously exercised by parliament before the Nineteenth amendment. The government also cited concerns about the Chen case, then before the European Court of Justice, in which a Chinese woman who had been living in Wales had gone to give birth in Northern Ireland on legal advice. Mrs. Chen then pursued a case against the British Home Secretary to prevent her deportation from the United Kingdom on the basis of her child's right as a citizen of the European Union (derived from the child's Irish citizenship) to reside in a member state of the Union. (Ultimately Mrs. Chen won her case, but this was not clear until after the result of the referendum.) Both the proposed amendment and the timing of the referendum were contentious but the result was decisively in favour of the proposal; 79% of those voting voted yes, on a turnout of 59%.[21]

The effect of the amendment was to prospectively restrict the constitutional right to citizenship by birth to those who are born on the island of Ireland to at least one parent who is (or is someone entitled to be) an Irish citizen. Those born on the island of Ireland before the coming into force of the amendment continue to have a constitutional right to citizenship. Moreover, jus soli primarily existed in legislation and it remained, after the referendum, for parliament to pass ordinary legislation that would modify it. This was done by the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2004 (the effects of which are detailed above). It remains, however, a matter for the legislature and unrestricted jus soli could be re-established by ordinary legislation without a referendum.

Acquisition of citizenship

At birth

A person born on the island of Ireland on or after 1 January 2005:[22]

- is automatically an Irish citizen if he or she is not entitled to the citizenship of any other country;[23] or

- is entitled to be an Irish citizen if at least one of his or her parents is:

- an Irish citizen (or someone entitled to be an Irish citizen);[24]

- a British citizen;[25]

- a resident of the island of Ireland who is entitled to reside in either the Republic or in Northern Ireland without any time limit on that residence;[26] or

- a legal resident of the island of Ireland for three out of the 4 years preceding the child's birth (although time spent as a student or as an asylum seeker does not count for this purpose).[27]

A person who is entitled to become an Irish citizen becomes an Irish citizen if:

- he or she does any act that only Irish citizens are entitled to do; or

- any act that only Irish citizens are entitled to do is done on his or her behalf by a person entitled to do so.[28]

Dual citizenship is permitted under Irish nationality law.

December 1999 to 2005

Ireland previously had a much less diluted application of jus soli (the right to citizenship of the country of birth) which still applies to anyone born on or before 31 December 2004. Although passed in 2001, the applicable law was deemed enacted on 2 December 1999[29] and provided that anyone born on the island of Ireland is:

- entitled to be an Irish citizen and

- automatically an Irish citizen if he or she was not entitled to the citizenship of any other country.

Prior to 1999

The previous legislation was largely replaced by the 1999 changes, which were retroactive in effect. Before 2 December 1999, the distinction between Irish citizenship and entitlement to Irish citizenship rested on the place of birth. Under this regime, any person born on the island of Ireland was:

- automatically an Irish citizen if born:

- on the island of Ireland before 6 December 1922,

- in the territory which currently comprises the Republic of Ireland, or

- in Northern Ireland on or after 6 December 1922 with a parent who was an Irish citizen at the time of birth;

- entitled to be an Irish citizen if born in Northern Ireland and not automatically an Irish citizen.[30]

The provisions of the 1956 Act were, in terms of citizenship by birth, retroactive and replaced the provisions of the previous legislation, the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1935. Under that legislation, those born in Northern Ireland on or after 6 December 1922 did not have an entitlement to Irish citizenship by birth. Citizenship of the Irish Free State was determined under the 1922 constitution, as amended by the Constitution (Amendment No. 26) Act 1935.

Children of diplomats

Like most countries, Ireland does not normally grant citizenship to the children of diplomats. This does not apply, however, when a diplomat parents a child with an Irish citizen, a British citizen or a permanent resident.[31] In 2001, Ireland enacted a measure which allowed the children of diplomats to register as Irish citizens if they chose to do so; however, this was repealed three years later.[32] The option to register remains for those born to diplomats before 2005.

By descent

A person is an Irish citizen by descent if, at the time of his or her birth, at least one of his or her parents was an Irish citizen. The place of that person's birth is not a deciding factor.[33] In cases where at least one parent was an Irish citizen born in the island of Ireland[33] or an Irish citizen not born on the island of Ireland but resident abroad in the public service,[34] citizenship is automatic and dates from birth. In all other cases citizenship is subject to registration in the Foreign Births Register.[35]

Due to legislative changes introduced in 1986, the Irish citizenship of those individuals requiring registration, dates from registration and not from birth, for citizenship registered on or after 1 January 1987.[36] Citizenship by registration had previously been back-dated to birth.

Anyone with an Irish citizen grandparent born on the island of Ireland is eligible for Irish citizenship. His or her parent would have automatically been an Irish citizen and their own citizenship can be secured by registering themselves in the Foreign Births Register. In contrast, those wishing to claim citizenship through an Irish citizen great-grandparent would be unable to do so unless their parents were placed into the Foreign Births Register. Their parents can transmit Irish citizenship to only those children born after they themselves were registered and not to any children born before registration.

Citizenship acquired through descent may be maintained indefinitely so long as each generation ensures its registration before the birth of the next.

By adoption

All adoptions performed or recognised under Irish law confer Irish citizenship on the adopted child (if not already an Irish citizen) if at least one of the adopters was an Irish citizen at the time of the adoption.[37]

By marriage

From 30 November 2005 (three years after the 2001 Citizenship Act came into force),[38] citizenship of the spouse of an Irish citizen must be acquired through the normal naturalisation process.[39] The residence requirement is reduced from 5 to 3 years in this case, and the spouse must intend to continue to reside in the island of Ireland.[40]

Previously, the law allowed for the spouses of most Irish citizens to acquire citizenship post-nuptially by registration without residence in the island of Ireland, or by naturalisation.[41]

- From 17 July 1956 to 31 December 1986,[42] the wife (but not the husband) of an Irish citizen (other than by naturalisation) could apply for post-nuptial citizenship. A woman who applied for this before marriage would become an Irish citizen upon marriage. This was a retrospective provision which could be applied to marriages made before 1956. However the citizenship granted was prospective only.[43]

- Between 1 July 1986[42] and 29 November 2005,[38] the spouse of an Irish citizen (other than by naturalisation, honorary citizenship or a previous marriage) could obtain post-nuptial citizenship after 3 years of subsisting marriage, provided the Irish spouse had held that status for at least 3 years. Like the provisions it replaced, the application of this regime was also retrospective.[44]

By naturalisation

The naturalisation of a foreigner as an Irish citizen is a discretionary power held by the Irish Minister for Justice. Naturalisation is granted on a number of criteria including good character, residence in the state and intention to continue residing in the state.

In principle the residence requirement is three years if married to an Irish citizen, and five years otherwise. Time spent seeking asylum will not be counted. Nor will time spent as an illegal immigrant. Time spent studying in the state by a national of a non-EEA state (i.e. a state other than European Union Member States, Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein) will not count.

The Minister for Justice may waive the residency requirement for:

- the children of naturalised citizens;

- recognised refugees;

- stateless children;

- those resident abroad in the service of the Irish state; and

- people of "Irish descent or Irish associations".

By grant of honorary citizenship

Section 12 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 allows the President, on advice of the Government, to "… grant Irish citizenship as a token of honour to a person, or the child or grandchild of a person who, in the opinion of the Government, has done signal honour or rendered distinguished service to the nation."[45]

Although known as "honorary Irish citizenship", this is in fact legally a full form of citizenship, with entitlement to an Irish passport and the other rights of Irish citizenship on the same basis as a naturalised Irish citizen. This has been awarded only a few times.[46] The first twelve people to have had honorary Irish citizenship conferred on them are:[47][48]

- Alfred Chester Beatty (1957) – art collector, philanthropist and founder of the Chester Beatty Library

- Tiede Herrema (1975) (and his wife, Elizabeth Herrema) – Dutch businessman kidnapped by the Provisional IRA

- Tip O'Neill (1986) (and his wife, Mildred Anne Miller O'Neill) – Irish-American and Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

- Alfred Beit (1993) (and his wife Clementine Mabell Kitty Beit, née Freeman-Mitford) – art collector and owner of Russborough House

- Jack Charlton (1996) (and his wife Pat Charlton) – for his achievements as manager of the Republic of Ireland national football team

- Jean Kennedy Smith (1998) – former United States Ambassador to Ireland

- Derek Hill (1999) – artist who established the Tory Island school of painting

- Don Keough (2007) - former president of Coca-Cola (Atlanta)

Plans were made to grant honorary Irish citizenship to U.S. president John F. Kennedy during his visit to Ireland in 1963, but this was abandoned owing to legal difficulties in granting citizenship to a foreign head of state.[49]

Loss of citizenship

By renunciation

An Irish citizen may renounce his or her citizenship if he or she is:

- eighteen years or older,

- ordinarily resident abroad, and

- is, or is about to become, a citizen of another country.

Renunciation is done by lodging a declaration with the Minister for Justice. If the person is not already a citizen of another country it is only effective when he or she becomes such. Irish citizenship cannot be lost by the operation of the law of another country,[50] but foreign law may require a person to renounce Irish citizenship before acquiring foreign nationality (see Multiple citizenship#Multiple citizenship avoided).

An Irish citizen born on the island of Ireland who renounces Irish citizenship remains entitled to be an Irish citizen and may resume it upon declaration.[51]

While not positively stated in the Act, the possibility of renouncing Irish citizenship is provided to allow Irish citizens to be naturalised as citizens of foreign countries whose laws do not allow for multiple citizenship. The Minister of Justice may revoke the citizenship of a naturalised citizen if he or she voluntarily acquires the citizenship of another country (other than by marriage) after naturalisation but there is no provision requiring them to renounce any citizenship they previously held. Similarly, there is no provision of Irish law requiring citizens to renounce their Irish citizenship before becoming citizens of other countries.

By revocation of a certificate of naturalisation

A certificate of naturalisation may be revoked by the Minister for Justice. Once revoked the person to whom the certificate applies ceases to be an Irish citizen. Revocation is not automatic and is a discretionary power of the Minister. A certificate may be revoked if it was obtained by fraud or when the naturalised citizen to whom it applies:

- resides outside the state (or outside the island of Ireland in respect to naturalised spouses of Irish citizens) for a period exceeding seven years, otherwise than in the public service, without registering annually his or her intention to retain Irish citizenship (this provision does not apply to those who were naturalised owing to their "Irish descent or Irish associations");

- voluntarily acquires the citizenship of another country (other than by marriage); or

- "has, by any overt act, shown himself to have failed in his duty of fidelity to the nation and loyalty to the State".[52]

A notice of the revocation of a certificate of naturalisation must be published in Iris Oifigiúil (the official gazette of the Republic), but in the years of 2002 to 2012 (inclusive) no certificates of naturalisation were revoked.[53][54]

Dual citizenship

Ireland allows its citizens to hold foreign citizenship in addition to their Irish citizenship.

Simultaneous lines of Irish and UK citizenship for descendants of pre-1922 Irish emigrants

Some descendants of Irish persons who left Ireland before 1922 may have claims to both Irish and British citizenship.

Under section 5 of the UK's Ireland Act 1949, a person who was born in the territory of the future Republic of Ireland as a British subject, but who did not receive Irish citizenship under that Act's interpretation of either the 1922 Constitution of the Irish Free State or the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1935 (because he or she was no longer domiciled in the Republic on the day that the Free State constitution came into force and was not permanently resident there on the day of the 1935 law's enactment and was not otherwise registered as an Irish citizen) was deemed by British law to be a Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies.[55][56]

As such, many of those individuals and some of the descendants in the Irish diaspora of an Irish person who left Ireland before 1922 (and who was also not resident in 1935) may be registrable for Irish citizenship while also having a claim to British citizenship,[57] through any of:

- birth to the first generation emigrant,

- consular registration of later generation births by a married father who was considered a British citizen under British law, within one year of birth, prior to the British Nationality Act (BNA) 1981 taking effect,[58][59]

- registration, at any time in life, with Form UKF, of birth to an unwed father who was considered a British citizen under British law,[60] or

- registration, at any time in life, with Form UKM, of birth to a mother who was considered a British citizen under British law, between the BNA 1948 and the BNA 1981 effective dates, under the UK Supreme Court's 2018 Romein principle.[58][59]

In some cases, British citizenship may be available to these descendants in the Irish diaspora even when Irish citizenship registration is not, as in instances of failure of past generations to timely register in a local Irish consulate's Foreign Births Register before the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986 and before births of later generations.[57]

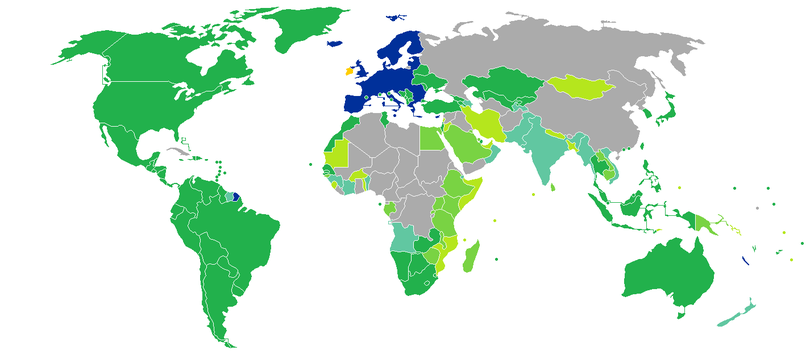

Citizenship of the European Union

Because Ireland forms part of the European Union, Irish citizens are also citizens of the European Union under European Union law and thus enjoy rights of free movement and have the right to vote in elections for the European Parliament.[61] When in a non-EU country where there is no Irish embassy, Irish citizens have the right to get consular protection from the embassy of any other EU country present in that country.[62][63] Irish citizens can live and work in any country within the EU as a result of the right of free movement and residence granted in Article 21 of the EU Treaty.[64]

Following the 2016 UK referendum on leaving the EU, which resulted in a vote to leave the European Union, there was a large increase in applications by British citizens for Irish passports, so that they can retain their rights as EU citizens after the UK's withdrawal from the EU. There were 25,207 applications for Irish passports from Britons in the 12 months before the referendum, and 64,400 in the 12 months after. Applications to other EU countries also increased by a large percentage, but were numerically much smaller.[65]

Travel freedom of Irish citizens

Visa requirements for Irish citizens are travel restrictions placed upon citizens of the Republic of Ireland by the authorities of other states. In 2018, Irish citizens had visa-free or visa on arrival access to 185 countries and territories, jointly ranking the Irish passport 6th worldwide according to the Henley Passport Index.[66][67]

The Irish nationality is ranked ninth in Nationality Index (QNI). This index differs from the Visa Restrictions Index, which focuses on external factors including travel freedom. The QNI considers, in addition, to travel freedom on internal factors such as peace & stability, economic strength, and human development as well.[68]

See also

Notes

- In Irish law the terms "nationality" and "citizenship" have equivalent meanings.

- According to Article 3 of the Free State Constitution Irish citizenship had previously only "within the limits of the jurisdiction of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann)". The Twenty Sixth amendment deleted the condition to extend the duties and right of Irish citizenship outside of the Free State.

- Dáil Debates, 14 February 1935, Vol. 54 No. 12 Col. 2049, Constitution (Amendment No. 26) Bill, 1934, Second Stage, The President.

- ‘Irish Nationality and Citizenship since 1922’ by Mary E. Daly, in ‘Irish Historical Studies’ Vol. 32, No. 127, May, 2001 (pp. 377-407)

- In re Logue [1933] 67 ILTR 253. The decision resulted in changes being made the British Nationality Act 1948 by section 5 the Ireland Act 1949, to ensure that people who were domiciled in Northern Ireland on 6 December 1922 but were born elsewhere in Ireland would not fail to become a "citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies" merely because they were also an Irish citizen.

- Brian Ó Caoindealbháin (2006) Citizenship and Borders: Irish Nationality Law and Northern Ireland. Centre for International Borders Research, Queen's University of Belfast and Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin. Accessed 04-06-09

- "Extract from a memorandum on nationality and citizenship". Documents on Irish Foreign Policy. Royal Irish Academy. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- Bauböck, Rainer, ed. (2006). Acquisition and Loss of Nationality: Policies and Trends in 15 European States. 2. Amsterdam University Press. p. 295. ISBN 9053569219.

- Daly, Mary (2001) "Irish nationality and citizenship since 1922", Irish historical studies 32 (127): 377-407. Cited in Ó Caoindealbháin (2006)

- Ó Caoindealbháin (2006), p.12

- Síofra O'Leary (1996) Irish nationality law, in B Nascimbene (ed.), Nationality laws in the European Union, Milan: Butterworths, cited in Ó Caoindealbháin (2006)

- Daly, Mary (2001) "Irish nationality and citizenship since 1922", Irish historical studies 32 (127):393

- Ó Caoindealbháin (2006)

- Brian Ó Caoindealbháin (2006) Citizenship and Borders: Irish Nationality Law and Northern Ireland. Centre for International Borders Research, Queen's University of Belfast and Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin

- Kelly, JM (1994) The Irish constitution, 3rd ed. Dublin: Butterworths, cited in Ó Caoindealbháin (2006)

- Daly, Mary (2001) “Irish nationality and citizenship since 1922”, Irish historical studies 32 (127): 377-407. Cited in Ó Caoindealbháin (2006)

- This is clearly the view of Denham, McGuinness and Hardiman JJ, in Osayande v. Minister for Justice, a view which is supported by the current writers of Kelly.

- The Irish Department of Justice granted leave to remain in the state to around 10,500 non-nationals between 1996 and February 2003 on the basis of their having an Irish born child – Department of Justice Press Release Archived 10 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- Osayande v. Minister for Justice

- Quoted from the Daíl debate.

- See: Twenty-seventh Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland

- This dates relates to the commencement date of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2004 and not the Twenty-seventh Amendment as is sometimes thought.

- Section 6(3) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- Sections 6(1), 6A(2)(b) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- Sections 6(1) and 6A(2)(c) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- Sections 6(1), 6A(2)(c) and (d) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- Sections 6(1), 6A(1) and 6B of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- Section 6(2) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- The relevant sections of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001 that was signed by the President on 5 June 2001, were backdated to apply from the changes made to Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish Constitution under the Good Friday Agreement: Minister for Justice, John O'Donoghue, Seanad Debates volume 161 column 982 (8 December 1999) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Sections 6(1) and 7(1) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956, as enacted.

- Section 6(6) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- Section 6(4) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004, as inserted by the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001 and later repealed by the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2004

- Section 7(1) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- Section 7(3)(b) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- Section 7(3) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- While the 1986 act, which brought in the registration requirement, came into force on 1 July 1986, section 8 of the Act allowed for a six-month transitional period when people could still register under the old provisions. See: Minister for Justice, Máire Geoghegan-Quinn, Dáil debates volume 140 column 131 Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine (21 April 1994); Minister of State at the Department of the Environment, Liz McManus, Seanad Debates volume 142 column 1730 Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine (4 April 1995).

- Section 11 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 as amended by section 175 of the Adoption Act 2010.

- Section 4 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001 came into force on 30 November 2002 by ministerial order: Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001 (Commencement) Order, 2002.

- The previous provisions having been repealed by section 4 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001.

- Sections 15A(1)(e) and (f) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 as inserted by the section 33 of the Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2011.

- Section 8 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 and section 3 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986.

- The Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986 came into force on 1 July 1986, section 8 of the Act allowed for a six-month transitional period during which both the new and old provisions were in force.

- Section 8 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 as enacted.

- Section 3 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986.

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 Section 12

- Irish Abroad Unit. "Presidential Distinguished Service Award for the Irish Abroad" (PDF). Dublin: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. pp. Sec.5. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

This provision has been invoked on only a small number of occasions and recipients have included Jack Charlton, Jean Kennedy Smith, Alfred Beit, Alfred Chester Beatty and to Mr and Mrs Tip O’Neill.

- McDowell, Michael (30 November 2004). "Irish Nationality and Citizenship Bill 2004: Report Stage (Resumed)". Dáil debates. p. Vol.593 No.5 p.23 c.1181. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Anderson, Nicola (14 January 1999). "Artist made honorary citizen". Irish Independent. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

Dr Hill is just the 11th person to be awarded honorary citizenship since the foundation of the State.

- Sniper threat sparked alert during 1963 Kennedy visit — The Irish Times newspaper article, 29 December 2006.

- Section 21 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004

- Section 6(5) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- Section 19(1)(b) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004

- See the Official journal's Website. The period reflects the length of the Gazette's availability online.

- "PQ: NATURALISATION APPLICATIONS (REVOKED)". NASC The Irish Immigrant Support Centre. 28 May 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- R. F. V. Heuston (January 1950). "British Nationality and Irish Citizenship". International Affairs. 26 (1): 77–90. doi:10.2307/3016841. JSTOR 3016841.

- "Ireland Act: Section 5", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1949 c. 41 (s. 5)

- Daly, Mary E. (May 2001). "Irish Nationality and Citizenship since 1922". Irish Historical Studies. Cambridge University Press. 32 (127): 395, 400, 406. JSTOR 30007221.

- Khan, Asad (23 February 2018). "Case Comment: The Advocate General for Scotland v Romein (Scotland) [2018] UKSC 6, Part One". UK Supreme Court Blog.

- The Advocate General for Scotland (Appellant) v Romein (Respondent) (Scotland) [2018] UKSC 6, [2018] A.C. 585 (8 February 2018), Supreme Court (UK)

- "Nationality: Registration as a British Citizen" (PDF). Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association. 14 August 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "Ireland". European Union. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Article 20(2)(c) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- Rights abroad: Right to consular protection: a right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other Member States when in a non-EU Member State, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state (Article 23): this is due to the fact that not all member states maintain embassies in every country in the world (14 countries have only one embassy from an EU state). Antigua and Barbuda (UK), Barbados (UK), Belize (UK), Central African Republic (France), Comoros (France), Gambia (UK), Guyana (UK), Liberia (Germany), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (UK), San Marino (Italy), São Tomé and Príncipe (Portugal), Solomon Islands (UK), Timor-Leste (Portugal), Vanuatu (France)

- "Treaty on the Function of the European Union (consolidated version)" (PDF). Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Morris, Chris (29 September 2017). "Brexit: Are more British nationals applying for dual nationality in the EU? - BBC News". BBC. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Ranks are assigned using dense ranking. A standard ranking places the Irish passport joint 16th.

- "Global Ranking - Henley Passport Index 2018". Henley & Partners. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "The 41 nationalities with the best quality of life". www.businessinsider.de. 6 February 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

References

- J.M. Kelly, The Irish Constitution 4th edn. by Gerard Hogan and Gerard Whyte (2002) ISBN 1-85475-895-0

- Brian Ó Caoindealbháin (2006) Citizenship and Borders: Irish Nationality Law and Northern Ireland. Centre for International Borders Research, Queen's University of Belfast and Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin

External links

- Irish Department of Justice and Equality: Citizenship government website

- Repealed Acts of the Irish Free State:

- Acts in force:

- Irish Nationality & Citizenship Acts 1956-2004 (unofficial consolidated version) - pdf format

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1994

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2004

- Information on Irish citizenship from the Citizens Information Board

- Wives, mothers and citizens - the treatment of women in the 1935 Nationality & Citizenship Act

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Bill, 1985: Second Stage

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Bill, 1994: Second Stage