Colony of Vancouver Island

The Colony of Vancouver Island, officially known as the Island of Vancouver and its Dependencies, was a Crown colony of British North America from 1849 to 1866, after which it was united with the mainland to form the Colony of British Columbia. The united colony joined Canadian Confederation, thus becoming part of Canada, in 1871. The colony comprised Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands of the Strait of Georgia.

Island of Vancouver and its Dependencies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1849–1866 | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Status | British colony | ||||||

| Capital | Victoria | ||||||

| Common languages | English | ||||||

| Religion | Christianity | ||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||

| Queen regnant | |||||||

| Historical era | British Era | ||||||

• Established | 13 January 1849 | ||||||

• Merged with Colony of British Columbia (1858–66) to form Colony of British Columbia (1866–71) | November 1866 | ||||||

| |||||||

Settlement of the island

Captain James Cook was the first European to set foot on the Island at Nootka Sound in 1778, during his third voyage. He spent a month in the area, claiming the territory for Great Britain. Fur trader John Meares arrived in 1786 and set up a single-building trading post near the native village of Yuquot (Friendly Cove), at the entrance to Nootka Sound in 1788.[1] The fur trade began expanding across the island; this would eventually lead to permanent settlement.[2]

Sovereignty dispute

Spain also explored the area. Esteban Jose Martinezand built a fort at Friendly Cove on Vancouver Island in 1789 and seized some British ships, claiming sovereignty. The fort was re-established in 1790 by Francisco de Eliza and a small community was built around it. Ownership of the island remained in dispute between Spain and Britain.

In 1792 Captain George Vancouver arrived to meet with Spanish commander Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra but their lengthy negotiations failed to produce a decision. Ownership of the island remained in dispute between Britain and Spain. The two countries nearly began a war over the issue; the confrontation became known as the Nootka Crisis. That was averted when both agreed to recognize the other's rights to the area in the first Nootka Convention in 1790, a first step to peace.[3] Finally, the two countries signed the second Nootka Convention in 1793 and the third Convention in 1794. As per that final agreement, the Spanish dismantled their fort at Nootka and left the area, giving the British sovereignty over Vancouver Island and the adjoining islands (including the Gulf Islands).[4]

Early British settlement

It was not until 1843 that Britain – under the auspices of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) – established a settlement on Vancouver Island. In March of that year, James Douglas of the Hudson's Bay Company and a missionary had arrived and selected an area for settlement. Construction of the fort began in June of that year.[5] This settlement was a fur trading post originally named Fort Albert (afterward Fort Victoria). The fort was located at the Songhees settlement of Camosack (Camosun), 200 metres northwest of the present-day Empress Hotel on Victoria's Inner Harbour.

In 1846, the Oregon Treaty was signed by the British and the U.S. to settle the question of the U.S. Oregon Territory borders.[6] The Treaty made the 49th parallel latitude north the official border between the two countries. In order to ensure that Britain retained all of Vancouver Island and the southern Gulf Islands, however, it was agreed that the border would swing south around that area.[7]

Colony

In 1849, the Colony of Vancouver Island was established. The Colony was leased to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) for ten years, at an annual fee of seven shillings. Thus in 1849, HBC moved its western headquarters from Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River (present day Vancouver, Washington) to Fort Victoria. Chief Factor James Douglas, was relocated from Fort Vancouver to Fort Victoria to oversee the Company's operations west of the Rockies.[8]

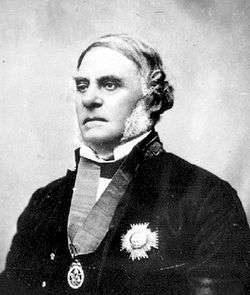

The British colonial office designated the territory a Crown colony on 13 January 1849. Douglas was charged with encouraging British settlement. Richard Blanshard was named the colony's governor. Blanshard discovered that the hold of the HBC over the affairs of the new colony was all but absolute, and that it was Douglas who held all practical authority in the territory. There was no civil service, no police, no militia, and virtually every British colonist was an employee of the HBC. Frustrated, Blanshard abandoned his post a year later, returning to England. In 1851, his resignation was finalised, and the colonial office appointed Douglas as governor.

Douglas governorship

Douglas's situation as both the local chief executive of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) as well as the civil governor of the colony from whom the company had leased all rights, was barely tenable from the outset. Initially, Douglas performed the delicate balancing act well, raising a domestic militia and encouraging settlement. By the mid-1850s, the colony's non-aboriginal population was approaching 500, and sawmill and coal mining operations had been established at Fort Nanaimo and Fort Rupert (near present-day Port Hardy). Douglas also assisted the British government in establishing a naval base at present-day Esquimalt to check Russian and American expansionism.

Douglas's efforts at encouraging settlement were hampered by colonial officials in London who were given incentives to bring out labourers with them to work the landholdings. The result was that emigration was slow, and the landless labourers frequently fled the colony either to obtain free land grants in the United States, or work the newly discovered goldfields of California. A secondary result was the replication of the British class system, with the attendant resistance to non-parochial education, land reform, and representative government.

At the time of the establishment of the colony, Vancouver Island had a large and varied First Nations population of upwards of 30,000. Douglas completed fourteen separate treaties with the various nations, or tribes. Under the terms of these treaties, known today as the Douglas Treaties, the nations were obliged to surrender title to all land within a designated area, with the exception of villages and cultivated areas, in perpetuity. They were also given permission to hunt and fish over unoccupied territories. For these concessions, the nations were given a one-time cash payment of a few shillings each.

As settlement accelerated, resentment towards the HBC's monopoly – both economic and civil – over the colony swelled. A series of petitions were sent to the colonial office, one of which resulted in the establishment of the Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island in 1855. At first, little changed, given that only a few dozen men met the voting requirement of holding twenty or more acres. Moreover, the majority of the representatives were employees of the HBC. However, as time went on, the franchise was gradually extended, and the assembly began to assert demands for more control over colonial affairs and criticised Douglas's inherent conflict of interest.

By 1857, Americans and British colonists were beginning to respond to rumours of gold in the Thompson River area. Almost overnight, some ten to twenty thousand men moved into the interior of New Caledonia (mainland British Columbia), and Victoria was transformed into a tent-city of prospectors, merchants, land-agents, and speculators. Douglas – who had no legal authority over New Caledonia – stationed a gunboat at the entrance of the Fraser River to exert British authority by collecting licences from boats attempting to make their way upstream. To exert its legal authority, and undercut any HBC claims to the resource wealth of the mainland, the district was converted to a Crown colony on 2 August 1858, and given the name British Columbia. Douglas was offered the governorship of the new colony, on condition that he sever his relationship with the HBC. Douglas accepted these conditions, and a knighthood, and for the next six years would govern both colonies from Victoria.

The remainder of Douglas's term as Vancouver Island governor (until 1864) was marked by increased expansion of the economy and settlement, and greater agitation for both union of the two colonies and for the introduction of fully responsible government. It was also marked by occasional boundary disputes with the United States, the most significant of which was the San Juan Boundary Dispute in 1859. This resulted in a sometimes tense, twelve-year military standoff as the two countries garrisoned troops on San Juan Island. There was a second gold rush – the Cariboo Gold Rush – and again Victoria experienced an economic boom as the staging point for the prospectors.

The increased conflicts between Douglas and the reformers, such as Amor De Cosmos, along with the growing desire of colonists in British Columbia to have a resident governor in their capital of New Westminster resulted in the colonial office easing Douglas into retirement in 1864.

Union of Vancouver Island and British Columbia

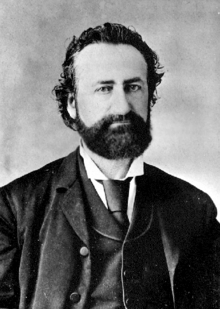

Douglas was succeeded as governor in 1864 by Sir Arthur Edward Kennedy, a career colonial administrator who had previously served as governor of Sierra Leone and Western Australia. There was popular acclaim for the appointment of a governor free from ties with the HBC. The Company had leased the island from Britain during 1849-1859 and still exerted a great deal of influence because the previous Governor, James Douglas was the executive officer of HBC.[10]

After Arthur Kennedy was appointed Governor, his rule was initially met with suspicion and opposition by the colonial assembly, which feared the loss of Vancouver Island's status vis-à-vis the growing power of the mainland colony. It resisted the colonial office's request for the permanent appropriation for the civil list in return for control of the extensive Crown lands of the colony, and temporarily withheld salary and housing to Kennedy until they had achieved their aim. Kennedy met with further opposition by some in the assembly over the plan for the colony to unite with British Columbia. It was only when opponents were persuaded that such union would boost the colony's ailing economy that passage of the proposal was assured by the assembly.

Kennedy achieved some progress in breaking down the longstanding social barriers established over years of HBC hegemony. In 1865, the Common Schools Act funded public education.[11] Kennedy also reformed the civil service, introduced auditing of the colonial budget, and improved revenue collection. Nonetheless, he continued to fail in his efforts to persuade the assembly to introduce the vote of a civil list, as well as enforcing various measures to protect the rights and well-being of the increasingly pressured aboriginal population. Despite his sympathy for the plight of neighbouring Indian peoples, Kennedy authorised naval bombardment of the Ahousahts of Clayoquot Sound in 1864 in reprisal for the murder of the crew of a trading vessel. Nine Ahousaht villages were destroyed, and thirteen people killed.[12]

Fort Victoria became the City of Victoria in 1862 with Thomas Harris elected Mayor.[13] With the colony's budget collapsing by 1865, and the assembly unwilling and unable to introduce proposals for raising revenue, Kennedy was barely able to keep the administration afloat.[14] Pressure grew for amalgamation with the mainland Colony of British Columbia (which had been established in 1858).

The two colonies were merged in 1866 into the United Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia by the Act for the Union of the colonies, passed by the Imperial Parliament.[15] Kennedy was appointed governor of the united entity. (He would leave office in 1866 and later became Governor of the West African Settlements, British West Africa.)[16] Victoria became the capital but the legislative assembly was located in New Westminster on the Lower Mainland. The capital was moved to Victoria in 1868.[17]

Confederation

By 1867, Canadian Confederation was accomplished by the British North America Act, and the united colonies joined Canada on 20 July 1871. Victoria was named the capital of the province of British Columbia. Three delegates were appointed to the federal government.[18][19]

Governors of Vancouver Island

- Richard Blanshard, 1849–1851

- Sir James Douglas, 1851–1864

- Sir Arthur Kennedy, 1864–1866

Elections to the Legislative Assembly of Vancouver Island

- 1856 Vancouver Island Election

- 1860 Vancouver Island Election

- 1863 Vancouver Island Election

See also

- Colony of British Columbia (1858–1866)

- Colony of British Columbia (1866–1871)

- Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands

- Former colonies and territories in Canada

- History of British Columbia

- List of Governors of Vancouver Island and British Columbia

- Postage stamps and postal history of British Columbia

- Pugets Sound Agricultural Company

- Territorial evolution of Canada after 1867

Further reading

- Representative Government Established chapter, A History of British Columbia, R. Gosnell & E.O.S. Scholefield, British Columbia Historical Association (Vancouver 1913) pp. 115–128

- Union and Confederation chapter, A History of British Columbia, R. Gosnell & E.O.S. Scholefield, British Columbia Historical Association (Vancouver 1913) pp. 193–210 – detailed account of issues and deliberations on colonial union and entry to Confederation

- The Colony of Vancouver Island: 1849 to 1855. Bob Reid, The Scrivener, October 2003.

References

- "Early European Exploration in Nootka Sound". Get West. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "History of Victoria". City of Victoria. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Vancouver Island History". Discover Vancouver Island. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Early European Exploration in Nootka Sound". Get West. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "History of Victoria". City of Victoria. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Places". Our History. Hbc Heritage. Archived from the original on 6 December 2004. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Britain and the United States agree on the 49th parallel as the main Pacific Northwest boundary in the Treaty of Oregon on June 15, 1846". History Link. 13 July 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "History of Victoria". City of Victoria. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Vancouver Island History timeline". Tourism Vancouver Island. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "A Highlight History of British Columbia Schools" (PDF). Royal BC Museum. 15 March 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "KENNEDY, Sir ARTHUR EDWARD". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "History of Victoria". City of Victoria. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "KENNEDY, Sir ARTHUR EDWARD". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "History of Victoria". City of Victoria. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "KENNEDY, Sir ARTHUR EDWARD". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "History of Victoria". City of Victoria. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Vancouver Island History timeline". Tourism Vancouver Island. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "History of Victoria". City of Victoria. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.