French colonization of the Americas

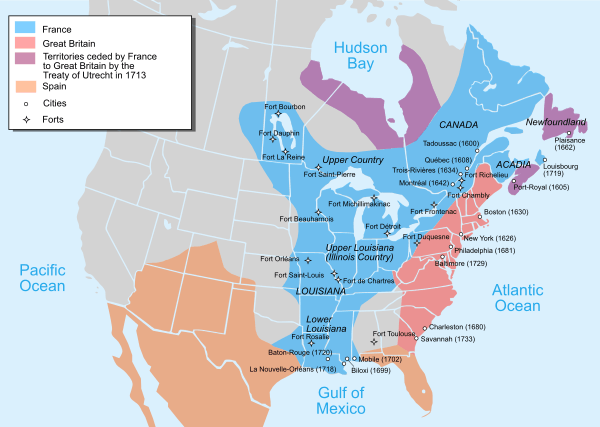

The French colonization of the Americas began in the 17th century, and continued on into the following centuries as France established a colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere. France founded colonies in much of eastern North America, on a number of Caribbean islands, and in South America. Most colonies were developed to export products such as fish, rice, sugar, and furs.

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

|

As they colonized the New World, the French established forts and settlements that would become such cities as Quebec and Montreal in Canada; Detroit, Green Bay, St. Louis, Cape Girardeau, Mobile, Biloxi, Baton Rouge and New Orleans in the United States; and Port-au-Prince, Cap-Haïtien (founded as Cap-Français) in Haiti, Cayenne in French Guiana and São Luís (founded as Saint-Louis de Maragnan) in Brazil.

North America

Background

The French first came to the New World as travelers, seeking a route to the Pacific Ocean and wealth. Major French exploration of North America began under the rule of Francis I, King of France. In 1524, Francis sent Italian-born Giovanni da Verrazzano to explore the region between Florida and Newfoundland for a route to the Pacific Ocean. Verrazzano gave the names Francesca and Nova Gallia to that land between New Spain and English Newfoundland, thus promoting French interests.[1]

Colonization

In 1534, Francis I of France sent Jacques Cartier on the first of three voyages to explore the coast of Newfoundland and the St. Lawrence River. He founded New France by planting a cross on the shore of the Gaspé Peninsula. The French subsequently tried to establish several colonies throughout North America that failed, due to weather, disease, or conflict with other European powers. Cartier attempted to create the first permanent European settlement in North America at Cap-Rouge (Quebec City) in 1541 with 400 settlers but the settlement was abandoned the next year after bad weather and attacks from Native Americans in the area. A small group of French troops were left on Parris Island, South Carolina in 1562 to build Charlesfort, but left after a year when they were not resupplied by France. Fort Caroline established in present-day Jacksonville, Florida, in 1564, lasted only a year before being destroyed by the Spanish from St. Augustine. An attempt to settle convicts on Sable Island off Nova Scotia in 1598 failed after a short time. In 1599, a sixteen-person trading post was established in Tadoussac (in present-day Quebec), of which only five men survived the first winter. In 1604[2] Pierre Du Gua de Monts and Samuel de Champlain founded a short-lived French colony, the first in Acadia, on Saint Croix Island, presently part of the state of Maine, which was much plagued by illness, perhaps scurvy. The following year the settlement was moved to Port Royal, located in present-day Nova Scotia.

Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec (1608) and explored the Great Lakes. In 1634, Jean Nicolet founded La Baye des Puants (present-day Green Bay), which is one of the oldest permanent European settlements in America. In 1634, Sieur de Laviolette founded Trois-Rivières. In 1642, Paul de Chomedey, Sieur de Maisonneuve, founded Fort Ville-Marie which is now known as Montreal. Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette founded Sault Sainte Marie (1668) and Saint Ignace (1671) and explored the Mississippi River. At the end of the 17th century, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle established a network of forts going from the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence River. Fort Saint Louis was established in Texas in 1685, but was gone by 1688. Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac founded Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit (modern-day Detroit) in 1701 and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville founded La Nouvelle Orléans (New Orleans) in 1718. Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville founded Baton Rouge in 1719.

.[3]

The French were eager to explore North America but New France remained largely unpopulated. Due to the lack of women, intermarriages between French and Indians were frequent, giving rise to the Métis people. Relations between the French and Indians were usually peaceful. As the 19th-century historian Francis Parkman stated:

"Spanish civilization crushed the Indian; English civilization scorned and neglected him; French civilization embraced and cherished him"

— Francis Parkman.[4]

To boost the French population, Cardinal Richelieu issued an act declaring that Indians converted to Catholicism were considered as "natural Frenchmen" by the Ordonnance of 1627:

"The descendants of the French who are accustomed to this country [New France], together with all the Indians who will be brought to the knowledge of the faith and will profess it, shall be deemed and renowned natural Frenchmen, and as such may come to live in France when they want, and acquire, donate, and succeed and accept donations and legacies, just as true French subjects, without being required to take no letters of declaration of naturalization."[5]

Louis XIV also tried to increase the population by sending approximately 800 young women nicknamed the "King's Daughters". However, the low density of population in New France remained a very persistent problem. At the beginning of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the British population in North America outnumbered the French 20 to 1. France fought a total of six colonial wars in North America (see the four French and Indian Wars as well as Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War).[6]

French Florida

In 1562, Charles IX, under the leadership of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny sent Jean Ribault and a group of Huguenot settlers in an attempt to colonize the Atlantic coast and found a colony on a territory which will take the name of the French Florida. They discovered the probe and Port Royal Island, which will be called by Parris Island in South Carolina, on which he built a fort named Charlesfort. The group, led by René Goulaine de Laudonnière, moved to the south where they founded the Fort Caroline on the Saint John's river in Florida on June 22, 1564.[7]

This irritated the Spanish who claimed Florida and opposed the Protestant settlers for religious reasons. In 1565, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés led a group of Spaniards and founded Saint Augustine, 60 kilometers south of Fort Caroline. Fearing a Spanish attack, Ribault planned to move the colony but a storm suddenly destroyed his fleet. On 20 September 1565 the Spaniards, commanded by Menéndez de Avilés, attacked and massacred all the Fort Caroline occupants including Jean Ribault.[8]

Canada and Acadia

The French interest in Canada focused first on fishing off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. However, at the beginning of the 17th century, France was more interested in fur from North America. The fur trading post of Tadoussac was founded in 1600. Four years later, Champlain made his first trip to Canada in a trade mission for fur. Although he had no formal mandate on this trip, he sketched a map of the St. Lawrence River and in writing, on his return to France, a report entitled Savages[9] (relation of his stay in a tribe of Montagnais near Tadoussac).

Champlain needed to report his findings to Henry IV. He participated in another expedition to New France in the spring of 1604, conducted by Pierre Du Gua de Monts. It helped the foundation of a settlement on Saint Croix Island, the first French settlement in the New World, which would be given up the following winter. The expedition then founded the colony of Port-Royal.

In 1608, Champlain founded a fur post that would become the city of Quebec, which would become the capital of New France. In Quebec, Champlain forged alliances between France and the Huron and Ottawa against their traditional enemies, the Iroquois. Champlain and other French travelers then continued to explore North America, with canoes made from Birch bark, to move quickly through the Great Lakes and their tributaries. In 1634, the Normand explorer Jean Nicolet pushed his exploration to the West up to Wisconsin.[10]

Following the capitulation of Quebec by the Kirke brothers, the British occupied the city of Quebec and Canada from 1629 to 1632. Samuel de Champlain was taken prisoner and there followed the bankruptcy of the Company of One Hundred Associates. Following the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France took possession of the colony in 1632. The city of Trois-Rivières was founded in 1634. In 1642, the Angevin Jérôme le Royer de la Dauversière founded Ville-Marie (later Montreal) which was at that time, a fort as protection against Iroquois attacks (the first great Iroquois war lasted from 1642 to 1667).

.jpg)

Despite this rapid expansion, the colony developed very slowly. The Iroquois wars and diseases were the leading causes of death in the French colony. In 1663 when Louis XIV provided the Royal Government, the population of New France was only 2500 European inhabitants. That year, to increase the population, Louis XIV sent between 800 and 900 'King's Daughters' to become the wives of French settlers. The population of New France reached subsequently 7000 in 1674 and 15000 in 1689.[11][12]

From 1689 to 1713, the French settlers were faced with almost incessant war during the French and Indian Wars. From 1689 to 1697, they fought the British in the Nine Years' War. The war against the Iroquois continued even after the Treaty of Rijswijk until 1701, when the two parties agreed on peace. Then, the war against the English took over in the War of the Spanish Succession. In 1690 and 1711, Quebec City had successfully resisted the attacks of the English navy and then British army. Nevertheless, the British took advantage of the second war. With the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, France ceded to Britain Acadia (with a population of 1700 people), Newfoundland and Hudson Bay. Under the Sovereign Council, the population of the colony grew faster. However, the population growth was far inferior to that of the British Thirteen Colonies to the south. In the middle of the 18th century, New France accounted for 60,000 people while the British colonies had more than one million people. This placed the colony at a great military disadvantage against the British. The war between the colonies resumed in 1744, lasting until 1748. A final and decisive war began in 1754. The Canadiens and the French were helped by numerous alliances with Native Americans, but they were usually outnumbered on the battlefield.[13]

Louisiana

On May 17, 1673, explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette began exploring the Mississippi River, known to the Sioux as does Tongo, or to the Miami-Illinois as missisipioui (the great river). They reached the mouth of the Arkansas and then up the river, after learning that it flowed into the Gulf of Mexico and not to the California Sea (Pacific Ocean).[14]

In 1682, the Normand Cavelier de la Salle and the Italian Henri de Tonti came down the Mississippi to its Delta. They left from Fort Crevecoeur on the Illinois River, along with 23 French and 18 Native Americans. In April 1682, they arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi; they planted a cross and a column bearing the arms of the king of France. In 1686 de Tonti left 6 men near the Quapaw village of Osotouy, creating the settlement of Arkansas Post. De Tonti's Arkansas Post would be the first European settlement in the Lower Mississippi River valley. La Salle returned to France and won over the Secretary of State of the Navy to give him the command of Louisiana. He believed that it was close to New Spain by drawing a map on which the Mississippi seemed much further west than its actual rate. He set up a maritime expedition with four ships and 320 emigrants, but it ended in disaster when he failed to find the Mississippi Delta and was killed in 1687.[15]

In 1698, Pierre LeMoyne d'Iberville left La Rochelle and explored the area around the mouth of the Mississippi. He stopped between Isle-aux-Chats (now Cat Island) and Isle Surgeres (renamed Isle-aux-Vascular or Ship Island) on February 13, 1699 and continued his explorations to the mainland, with his brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville to Biloxi. He built a precarious fort, called 'Maurepas' (later 'Old Biloxi'), before returning to France. He returned twice in the Gulf of Mexico and established a fort at Mobile in 1702.

From 1699 to 1702, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville was governor of Louisiana. His brother succeeded him in that post from 1702 to 1713. He was again governor from 1716 to 1724 and again 1733 to 1743. In 1718, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville commanded a French expedition in Louisiana. He founded the city of New Orleans, in homage to Regent Duke of Orleans. The architect Adrian de Pauger drew the orthogonal plane of the Old Square.

The Mississippi Bubble

In 1718, there were only 700 Europeans in Louisiana. The Mississippi Company arranged for ships to bring 800 more, who landed in Louisiana in 1718, doubling the European population. John Law encouraged Germans, particularly Germans of the Alsatian region who had recently fallen under French rule, and the Swiss to emigrate.

Prisoners were set free in Paris in September 1719 onwards, under the condition that they marry prostitutes and go with them to Louisiana. The newly married couples were chained together and taken to the port of embarkation. In May 1720, after complaints from the Mississippi Company and the concessioners about this class of French immigrants, the French government prohibited such deportations. However, there was a third shipment of prisoners in 1721.[16]

Dissolution

The last French and Indian War resulted in the dissolution of New France, with Canada going to Great Britain and Louisiana going to Spain. Only the islands of Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon are still in French hands.

In 1802 Spain returned Louisiana to France, but Napoleon sold it to the United States in 1803. The French left many toponyms (Illinois, Vermont, Bayous...) and ethnonyms (Sioux, Coeur d'Alene, Nez Percé...) in North America.

West Indies

A major French settlement lay on the island of Hispaniola, where France established the colony of Saint-Domingue on the western third of the island[17] in 1664. Nicknamed the "Pearl of the Antilles", Saint-Domingue became the richest colony in the Caribbean due to slave plantation production of sugar cane. It had the highest slave mortality rate in the western hemisphere.[18] A 1791 slave revolt, the only ever successful slave revolt, began the Haitian Revolution, led to freedom for the colony's slaves in 1794 and, a decade later, complete independence for the country, which renamed itself Haiti. France briefly also ruled the eastern portion of the island, which is now the Dominican Republic.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, France ruled much of the Lesser Antilles at various times. Islands that came under French rule during part or all of this time include Dominica, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Marie-Galante, Martinique, St. Barthélemy, St. Croix, St. Kitts, St. Lucia, St. Martin, St. Vincent and Tobago. Control of many of these islands was contested between the French, the British and the Dutch; in the case of St. Martin, the island was divided in two, a situation that persists to this day. Great Britain captured some of France's islands during the Seven Years' War[19] and the Napoleonic Wars. Following the latter conflict, France retained control of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Marie-Galante, St. Barthélemy, and its portion of St. Martin; all remain part of France today. Guadeloupe (including Marie-Galante and other nearby islands) and Martinique each is an overseas department of France, while St. Barthélemy and St. Martin each became an overseas collectivity of France in 2007.

South America

Brazil

France Antarctique (formerly also spelled France antartique) was a French colony south of the Equator, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, which existed between 1555 and 1567, and had control over the coast from Rio de Janeiro to Cabo Frio. The colony quickly became a haven for the Huguenots, and was ultimately destroyed by the Portuguese in 1567. On November 1, 1555, French vice-admiral Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon (1510–1575), a Catholic knight of the Order of Malta, who later would help the Huguenots to find a refuge against persecution, led a small fleet of two ships and 600 soldiers and colonists, and took possession of the small island of Serigipe in the Guanabara Bay, in front of present-day Rio de Janeiro, where they built a fort named Fort Coligny. The fort was named in honor of Gaspard de Coligny (then a Catholic statesman, who about a year later would become a Huguenot), an admiral who supported the expedition and would use the colony in order to protect his co-religionists. To the still largely undeveloped mainland village, Villegaignon gave the name of Henriville, in honour of Henry II, the King of France, who also knew of and approved the expedition, and had provided the fleet for the trip. Villegaignon secured his position by making an alliance with the Tamoio and Tupinambá Indians of the region, who were fighting the Portuguese.

1557 Calvinist arrival

Unchallenged by the Portuguese, who initially took little notice of his landing, Villegaignon endeavoured to expand the colony by calling for more colonists in 1556. He sent one of his ships, the Grande Roberge, to Honfleur, entrusted with letters to King Henry II, Gaspard de Coligny and according to some accounts, the Protestant leader John Calvin. After one ship was sent to France to ask for additional support, three ships were financed and prepared by the king of France and put under the command of Sieur De Bois le Comte, a nephew of Villegagnon. They were joined by 14 Calvinists from Geneva, led by Philippe de Corguilleray, including theologians Pierre Richier and Guillaume Chartrier. The new colonists, numbering around 300, included 5 young women to be wed, 10 boys to be trained as translators, as well as 14 Calvinists sent by Calvin, and also Jean de Léry, who would later write an account of the colony. They arrived in March 1557. The relief fleet was composed of: The Petite Roberge, with 80 soldiers and sailors was led by Vice Admiral Sieur De Bois le Comte. The Grande Roberge, with about 120 on board, captained by Sieur de Sainte-Marie dit l'Espine. The Rosée, with about 90 people, led by Captain Rosée. Doctrinal disputes arose between Villegagnon and the Calvinists, especially in relation to the Eucharist, and in October 1557 the Calvinists were banished from Coligny island as a result. They settled among the Tupinamba until January 1558, when some of them managed to return to France by ship together with Jean de Léry, and five others chose to return to Coligny island where three of them were drowned by Villegagnon for refusing to recant.

Portuguese intervention

In 1560 Mem de Sá, the new Governor-General of Brazil, received from the Portuguese government the command to expel the French. With a fleet of 26 warships and 2,000 soldiers, on 15 March 1560, he attacked and destroyed Fort Coligny within three days, but was unable to drive off their inhabitants and defenders, because they escaped to the mainland with the help of the Native Brazilians, where they continued to live and to work. Admiral Villegaignon had returned to France in 1558, disgusted with the religious tension that existed between French Protestants and Catholics, who had come also with the second group (see French Wars of Religion). Urged by two influential Jesuit priests who had come to Brazil with Mem de Sá, named José de Anchieta and Manuel da Nóbrega, and who had played a big role in pacifying the Tamoios, Mem de Sá ordered his nephew, Estácio de Sá to assemble a new attack force. Estácio de Sá founded the city of Rio de Janeiro on March 1, 1565, and fought the Frenchmen for two more years. Helped by a military reinforcement sent by his uncle, on January 20, 1567, he imposed final defeat on the French forces and decisively expelled them from Brazil, but died a month later from wounds inflicted in the battle. Coligny's and Villegaignon's dream had lasted a mere 12 years.

Equinoctial France

Equinoctial France was the contemporary name given to the colonization efforts of France in the 17th century in South America, around the line of Equator, before "tropical" had fully gained its modern meaning: Equinoctial means in Latin "of equal nights", i.e., on the Equator, where the duration of days and nights is nearly the same year round. The French colonial empire in the New World also included New France (Nouvelle France) in North America, particularly in what is today the province of Quebec, Canada, and for a very short period (12 years) also Antarctic France (France Antarctique, in French), in present-day Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. All of these settlements were in violation of the papal bull of 1493, which divided the New World between Spain and Portugal. This division was later defined more exactly by the Treaty of Tordesillas.

History of France équinoxiale

France équinoxiale started in 1612, when a French expedition departed from Cancale, Brittany, France, under the command of Daniel de la Touche, Seigneur de la Ravardière, and François de Razilly, admiral. Carrying 500 colonists, it arrived in the Northern coast of what is today the Brazilian state of Maranhão. De la Ravardière had discovered the region in 1604 but the death of the king postponed his plans to start its colonization. The colonists soon founded a village, which was named "Saint-Louis", in honor of the French king Louis IX. This later became São Luís in Portuguese,[1] the only Brazilian state capital founded by France. On 8 September, Capuchin friars prayed the first mass, and the soldiers started building a fortress. An important difference in relation to France Antarctique is that this new colony was not motivated by escape from religious persecutions to Protestants (see French Wars of Religion). The colony did not last long. A Portuguese army assembled in the Captaincy of Pernambuco, under the command of Alexandre de Moura, was able to mount a military expedition, which defeated and expelled the French colonists in 1615, less than four years after their arrival in the land. Thus, it repeated the disaster spelt for the colonists of France Antarctique, in 1567. A few years later, in 1620, Portuguese and Brazilian colonists arrived in number and São Luís started to develop, with an economy based mostly in sugar cane and slavery.

.svg.png)

French traders and colonists tried again to settle a France Équinoxiale further North, in what is today French Guiana, in 1626, 1635 (when the capital, Cayenne, was founded) and 1643. Twice a Compagnie de la France équinoxiale was founded, in 1643 and 1645, but both foundered as a result of misfortune and mismanagement. It was only after 1674, when the colony came under the direct control of the French crown and a competent Governor took office, that France Équinoxiale became a reality. To this day, French Guiana is a department of France.[20]

French Guiana was first settled by the French in 1604, although its earliest settlements were abandoned in the face of hostilities from the indigenous population and tropical diseases. The settlement of Cayenne was established in 1643, but was abandoned. It was re-established in the 1660s. Except for brief occupations by the English and Dutch in the 17th century, and by the Portuguese in the 19th century, Guiana has remained under French rule ever since. From 1851 to 1951 it was the site of a notorious penal colony, Devil's Island (Île du Diable). Since 1946, French Guiana has been an overseas department of France.[21]

See also

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

|

- Atlantic World

- History of Canada

- Former colonies and territories in Canada

- French and Indian Wars

- Franco-Indian alliance

- French colonial empire

- French in Canada

- French in the United States

- French intervention in Mexico

- French West Indies

- Illinois Country

- List of French possessions and colonies

- List of French forts in North America

- Military of New France

- New France

- Timeline of imperialism#Colonization of North America

- Canadian French

Notes

- Thomas B. Costain, The white and the gold: the French regime in Canada (Doubleday, 2012) ch 1.

- https://umaine.edu/canam/publications/st-croix/champlain-and-the-settlement-of-acadia-1604-1607/

- Francis PArkman, The Pioneers of France in the New World (1865).

- Quoted in Cave, p. 42

- Acte pour l'établissement de la Compagnie des Cent Associés pour le commerce du Canada, contenant les articles accordés à la dite Compagnie par M. le Cardinal de Richelieu, le 29 avril 1627

- Peter N. Moogk, La Nouvelle-France: the making of French Canada : a cultural history (2000).

- John T. McGrath, The French in early Florida: in the eye of the hurricane (U Press of Florida, 2000).

- Bartolome Barrientos, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés: Founder of Florida (University of Florida Press, 1965).

- Des sauvages, ou, Voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouage, fait en la France Nouuelle, l'an mil six cens trois, A Paris : Chez Claude de Monstr'œil, tenant sa boutique en la Cour du Palais, au nom de Iesus, 1603. OCLC 71251137

- James MacPherson Le Moine, Quebec, Past and Present: a history of Quebec, 1608-1876 (1876). online

- Francis Parkman, Count Frontenac and New France under Louis XIV (1877)

- Hubert, et al. Charbonneau, "The population of the St-Lawrence Valley, 1608–1760." in A population history of North America (2000): 99-142.

- R. Cole Harris, Historical Atlas of Canada: Volume I: From the Beginning to 1800 (University of Toronto Press, 2016).

- Bennett H Wall and John C. Rodrigue, Louisiana: A History (2014( ch 1

- Francis Parkman, La Salle and the discovery of the Great West (1891). online

- Cat Island: The History of a Mississippi Gulf Coast Barrier Island, By John Cuevas

- "Hispaniola Article". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-313-33272-2.

- As the French and Indian War started two years earlier, and continued until the signing of the peace treaty, the name Seven Years' War is more properly applied to the European phase of the war.

- Philip Boucher, "French Proprietary Colonies In The Greater Caribbean, 1620s–1670s." in Constructing Early Modern Empires (Brill, 2007) pp. 163-188.

- Joshua R. Hyles (2013). Guiana and the Shadows of Empire: Colonial and Cultural Negotiations at the Edge of the World. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739187807.

References

- Brecher, Frank W. Losing a Continent: France's North American Policy, 1753-1763 (1998)

- Dechêne, Louise Habitants and Merchants in Seventeenth-Century Montreal (2003)

- Eccles, W. J. The Canadian Frontier, 1534-1760 (1983)

- Eccles, W. J. Essays on New France (1988)

- Eccles, W.J. The French in North America, 1500-1783 (Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, 1998.), a standard scholarly survey

- Havard, Gilles, and Cécile Vidal, "Making New France New Again: French historians rediscover their American past," Common-Place (July 2007) v 7 #4

- Holbrook, Sabra (1976), The French Founders of North America and Their Heritage, New York: Atheneum, ISBN 978-0-689-30490-3

- Katz, Ron. French America: French Architecture from Colonialization to the Birth of a Nation. Editions Didier Millet, 2004.

- McDermott, John Francis. The French in the Mississippi Valley (University of Illinois Press, 1965)

- McDermott, John F., ed. Frenchmen and French ways in the Mississippi Valley (1969)

- Marshall, Bill,ed. France and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History (3 Vol 2005)

- Moogk, Peter N. La Nouvelle France: The Making of French Canada -A Cultural History (2000). 340 pp.

- Trudel, Marcel. The Beginnings of New France 1524-1663 (1973)

- White, Sophie. Wild Frenchmen and Frenchified Indians: Material Culture and Race in Colonial Louisiana (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013)

In French

- Balvay, Arnaud. L'épée et la plume: Amérindiens et soldats des troupes de la marine en Louisiane et au Pays d'en Haut (1683-1763) (Presses Université Laval, 2006)

- Balvay, Arnaud. La Révolte des Natchez (Editions du Félin, 2008)

- Halford, Peter Wallace, and Pierre-Philippe Potier. Le français des Canadiens à la veille de la conquête: témoignage du père Pierre Philippe Potier, SJ. (Presses de l'Université d'Ottawa, 1994)

- Moussette, Marcel & Waselkov, Gregory A.: Archéologie de l'Amérique coloniale française. Lévesque éditeur, Montréal 2014. ISBN 978-2-924186-38-1 (print); ISBN 978-2-924186-39-8 (eBook)