First Anglo-Afghan War

The First Anglo-Afghan War (Pashto: د افغان-انگرېز لومړۍ جگړه, also known by the British as the Disaster in Afghanistan)[3] was fought between the British East India Company and the Pashtun tribesmen from 1839 to 1842. Initially, the British successfully intervened in a succession dispute between emir Dost Mohammad (Barakzai) and former emir Shah Shujah (Durrani), whom they installed upon conquering Kabul in August 1839. The main British Indian and Sikh force occupying Kabul along with their camp followers, having endured harsh winters as well, was almost completely annihilated while retreating in January 1842.[1][2] The British then sent an Army of Retribution to Kabul to avenge their defeat, and having demolished parts of the capital and recovered prisoners they left Afghanistan altogether by the end of the year. Dost Mohamed returned from exile in India to resume his rule.

It was one of the first major conflicts during the Great Game, the 19th century competition for power and influence in Central Asia between Britain and Russia.[4]

Causes

The 19th century was a period of diplomatic competition between the British and Russian empires for spheres of influence in Asia known as the "Great Game" to the British and the "Tournament of Shadows" to the Russians.[5] With the exception of Emperor Paul who ordered an invasion of India in 1800 (which was cancelled after his assassination in 1801), no Russian tsar ever seriously considered invading India, but for the most of the 19th century, Russia was viewed as "the enemy" in Britain; and any Russian advancement into Central Asia was always assumed (in London) to be directed towards the conquest of India, as the American historian David Fromkin observed, "no matter how far-fetched" such an interpretation might be.[6] In 1832, the First Reform Bill lowering the franchise requirements to vote and hold office in the United Kingdom was passed, which the ultra-conservative Emperor Nicholas I of Russia openly disapproved of, setting the stage for an Anglo-Russian "cold war", with many believing that Russian autocracy and British democracy were bound to clash.[7] In 1837, Lord Palmerston and John Hobhouse, fearing the instability of Afghanistan, the Sindh, and the increasing power of the Sikh kingdom to the northwest, raised the spectre of a possible Russian invasion of British India through Afghanistan. The Russian Empire was slowly extending its domain into Central Asia, and this was seen by the East India Company as a possible threat to their interests in India. In 19th century Russia, there was the ideology of Russia's "special mission in the East", namely Russia had the "duty" to conquer much of Asia, though this was more directed against the nations of Central Asia and the alleged "Yellow Peril" of China than India.[8] The British tended to misunderstand the foreign policy of the Emperor Nicholas I as anti-British and intent upon an expansionary policy in Asia; whereas in fact though Nicholas disliked Britain as a liberal democratic state that he considered to be rather "strange", he always believed it was possible to reach an understanding with Britain on spheres of influence in Asia, believing that the essentially conservative nature of British society would retard the advent of liberalism.[9] The main goal of Nicholas's foreign policy was not the conquest of Asia, but rather upholding the status quo in Europe, especially by co-operating with Prussia and Austria, and in isolating France, as Louis Philippe I, the King of the French was a man who Nicholas hated as an "usurper".[10] The duc d'Orleans had once been Nicholas's friend, but when he assumed the throne of France after the revolution of 1830, Nicholas was consumed with hatred for his former friend who, as he saw it, had gone over to what he perceived as the dark side of liberalism.[11]

The Company sent an envoy to Kabul to form an alliance with Afghanistan's Amir, Dost Mohammad Khan against Russia.[12][13] Dost Mohammad had recently lost Afghanistan's second capital of Peshawar to the Sikh Empire and was willing to form an alliance with Britain if they gave support to retake it, but the British were unwilling. Instead, the British feared the French-trained Dal Khalsa, and they considered the Sikh army to be a far more formidable threat than the Afghans who did not have an army at all, instead having only a tribal levy where under the banner of jihad tribesmen would come out to fight for the Emir.[14] The Dal Khalsa was an enormous force that had been trained by French officers, was equipped with modern weapons and was widely considered to be one of the most powerful armies on the entire Indian subcontinent. For this reason, Lord Auckland preferred an alliance with the Punjab over an alliance with Afghanistan, which had nothing equivalent to the Dal Khalsa.[14] The British could have had an alliance with the Punjab or Afghanistan, but not both at the same time.[14]

When Governor-General of India Lord Auckland heard about the arrival of Russian envoy Count Jan Prosper Witkiewicz (better known by the Russian version of his name as Yan Vitkevich) in Kabul and the possibility that Dost Mohammad might turn to Russia for support, his political advisers exaggerated the threat.[4] Alexander Burnes, the Scotsman who served as the East India Company's chief political officer in Afghanistan, described Witkiewicz: "He was a gentlemanly and agreeable man, of about thirty years of age, spoke French, Turkish and Persian fluently, and wore the uniform of an officer of the Cossacks".[15] The presence of Witkiewicz had thrown Burnes into a state of despair, leading one contemporary to note that he "abandoned himself to despair, bound his head with wet towels and handkerchiefs and took to the smelling bottle".[15] Dost Mohammad had in fact invited Count Witkiewicz to Kabul as a way to frighten the British into making an alliance with him against his archenemy Ranjit Singh, the Maharaja of the Punjab, not because he really wanted an alliance with Russia. The British had the power to compel Singh to return the former Afghan territories he had conquered whereas the Russians did not, which explains why Dost Mohammad Khan wanted an alliance with the British. Burnes wrote home after having dinner with Count Witkiewicz and Dost Mohammad in late December 1837: "We are in a mess home. The emperor of Russia has sent an envoy to Kabul to offer...money [to the Afghans] to fight Rajeet Singh!!! I could not believe my own eyes or ears."[14] On 20 January 1838, Lord Auckland sent an ultimatum to Dost Mohammad telling him: "You must desist from all correspondence with Russia. You must never receive agents from them, or have aught to do with them without our sanction; you must dismiss Captain Viktevitch [Witkiewicz] with courtesy; you must surrender all claims to Peshawar".[16] Burnes himself had complained that Lord Auckland's letter was "so dictatorial and supercilious as to indicate the writer's intention that it should give offense", and tried to avoid delivering it for long as possible.[17] Dost Mohammad was indeed offended by the letter, but in order to avoid a war, he had his special military advisor, the American adventurer Josiah Harlan engage in talks with Burnes to see if some compromise could be arranged.[18] Burnes in fact had no power to negotiate anything, and Harlan complained that Burnes was just stalling, which led to Dost Mohammad expelling the British diplomatic mission on 26 April 1838.[18]

British fears of a Russian invasion of India took one step closer to becoming a reality when negotiations between the Afghans and Russians broke down in 1838. The Qajar dynasty of Persia, with Russian support, attempted the Siege of Herat.[5] Herat is a city that had historically belonged to Persia that the Qajar shahs had long desired to take back and is located in a plain so fertile that is known as the "Granary of Central Asia"; whoever controls Heret and the surrounding countryside also controls the largest source of grain in all of Central Asia.[19] Russia, wanting to increase its presence in Central Asia, had formed an alliance with Qajar Persia, which had territorial disputes with Afghanistan as Herat had been part of the Safavid Persia before 1709. Lord Auckland's plan was to drive away the besiegers and replace Dost Mohammad with Shuja Shah Durrani, who had once ruled Afghanistan and who was willing to ally himself with anyone who might restore him to the Afghan throne. At one point, Shuja had hired an American adventurer Josiah Harlan to overthrow Dost Mohammad Khan, despite the fact Harlan's military experience comprised only working as a surgeon with the East India Company's troops in First Burma War.[20] Shuja Shah had been deposed in 1809 and been living in exile in British India since 1818, collecting a pension from the East India Company, which believed that he might be useful one day.[14] The British denied that they were invading Afghanistan, claiming they were merely supporting its "legitimate" Shuja government "against foreign interference and factious opposition."[2] Shuja Shah by 1838 was barely remembered by most of his former subjects and those that did viewed him as a cruel, tyrannical ruler who, as the British were soon to learn, had almost no popular support in Afghanistan.[21]

On 1 October 1838 Lord Auckland issued the Simla Declaration attacking Dost Mohammed Khan for making "an unprovoked attack" on the empire of "our ancient ally, Maharaja Ranjeet Singh", going on to declare that Suja Shah was "popular throughout Afghanistan" and would enter his former realm "surrounded by his own troops and be supported against foreign interference and factious opposition by the British Army".[21] As the Persians had broken off the siege of Herat and the Emperor Nicholas I of Russia had ordered Count Vitkevich home (he was to commit suicide upon reaching St. Petersburg), the reasons for attempting to put Shuja Shah back on the Afghan throne had vanished.[5] The British historian Sir John William Kaye wrote that the failure of the Persians to take Herat "cut from under the feet of Lord Auckland all ground of justification and rendered the expedition across the Indus at once a folly and a crime".[21] But at this point, Auckland was committed to putting Afghanistan into the British sphere of influence and nothing would stop him from going ahead with the invasion.[21] On 25 November 1838, the two most powerful armies on the Indian subcontinent assembled in a grand review at Ferozepore as Ranjit Singh, the Maharajah of the Punjab brought out the Dal Khalsa to march alongside the sepoy troops of the East India Company and the British troops in India with Lord Auckland himself present amid much colorful pageantry and music as men dressed in brightly colored uniforms together with horses and elephants marched in an impressive demonstration of military might.[22] Lord Auckland declared that the "Grand Army of the Indus" would now start the march on Kabul to depose Dost Mohammed and put Shuja Shah back on the Afghan throne, ostensibly because the latter was the rightful Emir, but in reality to place Afghanistan into the British sphere of influence.[5] The Duke of Wellington speaking in the House of Lords condemned the invasion, saying that the real difficulties would only begin after the invasion's success, predicating that Anglo-Indian force would rout the Afghan tribal levy, but then find themselves struggling to hold on given the terrain of the Hindu Kush mountains and Afghanistan had no modern roads, calling the entire operation "stupid" given that Afghanistan was a land of "rocks, sands, deserts, ice and snow".[21]

Forces

British India at this time was a proprietary colony run by the East India Company, which had been granted the right to rule India by the British Crown.[23] India was only one of several proprietary colonies in the British Empire around the world, where various corporations or individuals had been granted the right to rule by the Crown, with for instance Rupert's Land, which was a vast tract covering most of what is now Canada being ruled by the Hudson's Bay Company, but India was easily the most wealthy and profitable of all the proprietary colonies. By the 19th century, the East India Company ruled 90 million Indians and controlled 70m acres (243,000 square kilometres) of land under its own flag while issuing its own currency, making it into the most powerful corporation in the world.[24] The East India Company had been granted monopolies on trade by the Crown, but it was not owned by the Crown, through the shares in the East India Company were owned by numerous MPs and aristocrats, creating a powerful Company lobby in Parliament while the Company regularly gave "gifts" to influential people in Britain.[24] The East India Company was sufficiently wealthy to maintain the three Presidency armies, known after their presidencies as the Bengal Army, the Bombay Army and the Madras Army, with the supreme field headquarters for commanding these armies being at Simla.[21] The East India Company's army totaled 200,000 men, making it one of the largest armies in the entire world, and was an army larger than those maintained by most European states.[24] The majority of the men serving in the presidency armies were Indian, but the officers were all British, trained at the East India Company's own officer school at the Addiscombe estate outside of London.[25] Furthermore, the politically powerful East India Company had regiments from the British Army sent to India to serve alongside the East India Company's army.[25] Officers from the British Army serving in India tended to look down on officers serving in the Company's army as mercenaries and misfits, and relations between the two armies were cool at best.[25]

The regiments chosen for the invasion of Afghanistan came from the Bengal and Bombay armies.[25] The commander in India, Sir Henry Fane chose the regiments by drawing lots, which led to the best British regiment, the Third Foot, being excluded while the worst, the Thirteenth Light Infantry were included in the Grand Army of the Indus.[25] The units from the Bengal Army going into Afghanistan were Skinner's Horse, the Forty-third Native Infantry and the Second Light Cavalry, which were all Company regiments while the Sixteenth Lancers and the Thirteenth Light Infantry came from the British Army in India.[25] The units from the Bombay Army chosen for the Grand Army of the Indus were the Nineteenth Native Infantry and the Poona Local Horse, which were Company regiments, and the Second Foot battalion of the Coldstream Guards, the Seventeenth Foot, and the Fourth Dragoons, which were all British Army regiments.[25] Of the two divisions of the Grand Army of the Indus, the Bombay division numbered fifty-six hundred men and the Bengal division numbered ninety-five hundred men.[25] Shuja recruited 6,000 Indian mercenaries ("Shah Shujah's Levy")[26] out of his pocket for the invasion.[25] Ranjit Singh, the elderly and ailing Maharaja of the Punjab was supposed to contribute several divisions from the Dal Khalsa to the Grand Army of the Indus, but reneged on his promises, guessing that the Anglo-Indian force was sufficient to depose his archenemy Dost Mohammad, and he did not wish to occur the expenses of a war with Afghanistan.[14] Accompanying the invasion force were 38,000 Indian camp followers and 30,000 camels to carry supplies.[25]

The Emirate of Afghanistan had no army, and instead under the Afghan feudal system, the tribal chiefs contributed fighting men when the Emir called upon their services.[27] The Afghans were divided into numerous ethnic groups, of which the largest were the Pashtuns, the Tajiks, the Uzbeks, and the Hazaras, who were all in their turn divided into numerous tribes and clans. Islam was the sole unifying factor binding these groups together, through the Hazaras were Shia Muslims while the rest were Sunni Muslims. The Pashtuns were the dominant ethnic group, and it was with the Pashtun tribes that the British interacted the most. The Pashtun tribesmen had no military training, but the ferociously warlike Pashtuns were forever fighting each other, when not being called up for service for the tribal levy by the Emir, meaning most Pashtun men had at least some experience of warfare.[14] The Pashtun tribes lived by their strict moral code of Pashtunwali ("the way of the Pashtuns") stating various rules for a Pashtun man to live by, one of which was that a man had to avenge any insult, real or imagined, with violence, in order to be considered a man. The standard Afghan weapon was a matchlock rifle known as the jezail.[14]

British Indian invasion of Afghanistan

Into Afghanistan

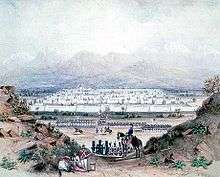

The "Army of the Indus" which included 21,000 British and Indian troops under the command of John Keane, 1st Baron Keane (subsequently replaced by Sir Willoughby Cotton and then by William Elphinstone) set out from Punjab in December 1838. With them was William Hay Macnaghten, the former chief secretary of the Calcutta government, who had been selected as Britain's chief representative to Kabul. It included an immense train of 38,000 camp followers and 30,000 camels, plus a large herd of cattle. The British intended to be comfortable – one regiment took its pack of foxhounds, another took two camels to carry its cigarettes, junior officers were accompanied by up to 40 servants, and one senior officer required 60 camels to carry his personal effects.[28]

By late March 1839 the British forces had crossed the Bolan Pass, reached the southern Afghan city of Quetta, and begun their march to Kabul. They advanced through rough terrain, across deserts and 4,000-metre-high mountain passes, but made good progress and finally set up camps at Kandahar on 25 April 1839. After reaching Kandahar, Keane decided to wait for the crops to ripen before resuming his march, so it was not until 27 June that the Grand Army of the Indus marched again.[29] Keane left behind his siege engines in Kandahar, which turned out to be a mistake as he discovered that the walls of the Ghazni fortress were far stronger than he expected.[29] A deserter, Abdul Rashed Khan, a nephew of Dost Mohammad Khan, informed the British that one of the gates of the fortress was in bad state of repair and might be blasted open with a gunpowder charge.[29] Before the fortress, the British were attacked by a force of the Ghilji tribesmen fighting under the banner of jihad who were desperate to kill farangis, a pejorative Pashtun term for the British and were beaten off.[30] The British took fifty prisoners who were brought before Shuja, where one of them stabbed a minister to death with a hidden knife.[30] Shuja had them all beheaded, which led Sir John Kaye, in his official history of the war, to write this act of "wanton barbarity", the "shrill cry" of the Ghazis, would be remembered as the "funeral wail" of the government's "unholy policy".[30]

On 23 July 1839, in a surprise attack, the British-led forces captured the fortress of Ghazni, which overlooks a plain leading eastward into the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.[31] The British troops blew up one city gate and marched into the city in a euphoric mood. In taking this fortress, they suffered 200 men killed and wounded, while the Afghans lost nearly 500 men. 1,600 Afghans were taken prisoner with an unknown number wounded. Ghazni was well-supplied, which eased the further advance considerably.

Following this, the British achieved a decisive victory over Dost Mohammad's troops, led by one of his sons. In August 1839, after thirty years, Shuja was again enthroned in Kabul. Shuja promptly confirmed his reputation for cruelty by seeking to wreak vengeance on all who had crossed him as he considered his own people to be "dogs" who needed to be taught to obey their master.[32]

Qalat/Kalat

On 13 November 1839, while en route to India, the Bombay column of the British Indian Army attacked, as a form of reprisal, the Baloch tribal fortress of Kalat,[33] from where Baloch tribes had harassed and attacked British convoys during the move towards the Bolan Pass.

Guerilla war

Dost Mohammad waged a guerilla war, being defeated in every skirmish he fought, but taunted Macnaughten in a letter with the boast: "I am like a wooden spoon. You may throw me hither and yon, but I shall not be hurt".[34] Dost Mohammad fled with his loyal followers across the passes to Bamyan, and ultimately to Bukhara. Nasrullah Khan, the emir of Bukhara violated the traditional code of hospitability by throwing Dost Mohammad into his dungeon, where he joined Colonel Charles Stoddart.[34] Stoddard had been sent to Bukhara to sign a treaty of friendship and arrange a subsidy to keep Bukhara in the British sphere of influence, but was sent to the dungeon which Nasrullah Khan decided the British were not offering him a big enough bribe.[34] Unlike Stoddart, Dost Mohammad was able to escape from the dungeon in August 1841 and fled south to Afghanistan.[34]

Occupation and rising of the Afghans

The majority of the British troops returned to India, leaving 8,000 in Afghanistan, but it soon became clear that Shuja's rule could only be maintained with the presence of a stronger British force. The Afghans resented the British presence and the rule of Shah Shuja. As the occupation dragged on, the East India Company's first political officer William Hay Macnaghten allowed his soldiers to bring their families to Afghanistan to improve morale;[35] this further infuriated the Afghans, as it appeared the British were setting up a permanent occupation.[36] Macnaughten purchased a mansion in Kabul, where he installed his wife, crystal chandelier, a fine selection of French wines, and hundreds of servants from India, making himself completely at home.[32] Macnaughten, who had once been a judge in a small town in Ulster before deciding he wanted to be much more than a small town judge in Ireland, was known for his arrogant, imperious manner, and was simply called "the Envoy" by both the Afghans and the British.[32] The wife of one British officer, Lady Florentia Sale created an English style garden at her house in Kabul, which was much admired and in August 1841 her daughter Alexadrina was married at her Kabul home to Lieutenant John Sturt of the Royal Engineers.[32] The British officers staged horse races, played cricket and in winter ice skating over the frozen local ponds, which astonished the Afghans who had never seen this before.[32]

The licentious conduct of the British troops greatly offended the puritanical values of the Afghan men who had always disapproved of premarital sex and were especially enraged to see British infidels take their womenfolk to their beds.[37] In his official history, Sir John William Kaye wrote he sadly had to declare "there are truths which must be spoken", namely there were "temptations which are most difficult to withstand and were not withstood by our English officers" as Afghan women were most attractive and those living in the zenanas (Islamic women's quarters) "were not unwilling to visit the quarters of the Christian stranger".[37] Kaye wrote the scandal was "open, undisguised, notorious" with British officers and soldiers openly having sexual relationships with Afghan women and in a nation like Afghanistan where women were and still are routinely killed in "honour killings" for the mere suspicion of engaging in premarital sex which is seen as a slur against the manhood of their male family members, most Afghan men were highly furious at what they saw as a national humiliation that had questioned their manhoods.[38] A popular ditty among the British troops was: "A Kabul wife under burkha cover, Was never known without a lover".[39] Some of these relationships ended in marriage as Dost Mohammad's niece Jahan Begum married Captain Robert Warburton and a Lieutenant Lynch married the sister of a Ghilzai chief; the fact that both women were very beautiful added to the humiliation of the Afghan men who did not like to see their women fall in love with infidels.[39] One Afghan nobleman Mirza 'Ata wrote: "The English drank the wine of shameless immodesty, forgetting that any act has its consequences and rewards-so that after a while, the spring garden of the King's regime was blighted by the autumn of these ugly events...The nobles complained to each other, "Day by day, we are exposed, because of the English, to deceit and lies and shame. Soon the women of Kabul will give birth to half-caste monkeys-it's a disgrace!"".[40] Afghanistan was such a desperately poor country that even the salary of a British private was considered to be a small fortune, and many Afghan women willingly become prostitutes as an easy way to get rich, much to the intense fury of their menfolk.[41] The East India Company's second political officer Sir Alexander Burnes was especially noted for his insatiable womanizing, settling an example ardently imitated by his men.[38] 'Ata wrote: "Burnes was especially shameless. In his private quarters, he would take a bath with his Afghan mistress in the hot water of lust and pleasure, as the two rubbed each other down with flannels of giddy joy and the talc of intimacy. Two memsahibs, also his lovers, would join them".[42] Of all the aspects of the British occupation, it was sex between Afghan women and British soldiers that most infuriated Afghan men.[39]

Afghanistan had no army, and instead had a feudal system under which the chiefs would maintain a certain number of armed retainers, principally cavalry together with a number of tribesmen who could be called upon to fight in a time of war; when the Emir went to war, he would call upon his chiefs to bring out their men to fight for him.[43] In 1840, the British strongly pressured Shuja to replace the feudal system with a standing army, which threatened to do away with the power of the chiefs, and which the Emir rejected under the grounds that Afghanistan lacked the financial ability to fund a standing army.[44]

Dost Mohammad unsuccessfully attacked the British and their Afghan protégé Shuja, and subsequently surrendered and was exiled to India in late 1840. In 1839–40, the entire rationale for the occupation of Afghanistan was changed by the Oriental Crisis when Mohammad Ali the Great, the vali (governor) of Egypt who was a close French ally, rebelled against the Sublime Porte; during the subsequent crisis, Russia and Britain co-operated against France, and with the improvement in Anglo-Russian relations, the need for a buffer state in Central Asia decreased.[45] The Oriental Crisis of 1840 almost caused an Anglo-French war, which given the long-standing Franco-Russian rivalry caused by Nicholas's detestation of Louis-Philippe as a traitor to the conservative cause, inevitably improved relations between London and St. Petersburg, which ultimately led to the Emperor Nicholas making an imperial visit to London in 1844 to meet Queen Victoria and the Prime Minister Lord Peel. As early as 1838, Count Karl Nesselrode, the Russian Foreign Minister, had suggested to the British Ambassador in St. Petersburg, Lord Clanricarde, that Britain and Russia sign a treaty delimiting spheres of influence in Asia to end the "Great Game" once and for all.[46] By 1840 Clanricarde was reporting to London that he was quite certain a mutually satisfactory agreement could be negotiated, and all he needed was the necessary permission from the Foreign Office to begin talks.[47] From Calcutta, Lord Auckland pressed for acceptance of the Russian offer, writing "I would look forward to a tripartite Treaty of the West under which a limit shall be placed to the advance of England, Russia and Persia and under which all shall continue to repress slave dealing and plunder".[47] Through Britain rejected the Russian offer, after 1840 there was a marked decline in Anglo-Russian rivalry and a "fair working relationship in Asia" had developed.[47] The British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston rejected the Russian offer to end the "Great Game" as he believed that as long as the "Great Game" continued, Britain could inconvenience Russia in Asia to better achieve her foreign policy goals in Europe much more than Russia could inconvenience Britain in Asia to achieve her foreign policy goals in Europe.[47] Palmerston noted that because the British had more money to bribe local rulers in Central Asia, this gave them the advantage in this "game", and it was thus better to keep the "Great Game" going.[47] Palmerston believed it was Britain that held the advantage in the "Great Game", that the Russian offer to definitely mark out spheres of influence in Asia was a sign of weakness and he preferred no such treaty be signed.[47] From Palmerston's viewpoint accepting the Russian offer would be unwelcome as the end of the "Great Game" in Asia would mean the redeployment of Russian power to Europe, the place that really counted for him, and it was better to keep the "Great Game" going, albeit at a reduced rate given the tensions with France.[47] At the same time, the lowering of Anglo-Russian tension in the 1840s made holding Afghanistan more of an expensive luxury from the British viewpoint as it not longer seemed quite as essential to have a friendly government in Kabul anymore.[47]

By this time, the British had vacated the fortress of Bala Hissar and relocated to a cantonment built to the northeast of Kabul. The chosen location was indefensible, being low and swampy with hills on every side. To make matters worse, the cantonment was too large for the number of troops camped in it and had a defensive perimeter almost two miles long. In addition, the stores and supplies were in a separate fort, 300 yards from the main cantonment.[48] The British commander, Major-General George Keith Ephinstone who arrived in April 1841 was bed-ridden most of the time with gout and rheumatism.[49]

Between April and October 1841, disaffected Afghan tribes were flocking to support Dost Mohammad's son, Akbar Khan, in Bamiyan and other areas north of the Hindu Kush mountains, organised into an effective resistance by chiefs such as Mir Masjidi Khan[50] and others. In September 1841, Macnaghten reduced the subsidies paid out to Ghazi tribal chiefs in exchange for accepting Shuja as Emir and to keep the passes open, which immediately led to the Ghazis rebelling and a jihad being proclaimed.[51] The monthly subsidies, which were effectively bribes for the Ghazi chiefs to stay loyal, was reduced from 80,000 to 40,000 rupees at a time of rampant inflation, and as the chiefs' loyalty had been entirely financial, the call of jihad proved stronger.[51] Macnaughten did not take the threat seriously at first, writing to Henry Rawlinson in Kandahar on 7 October 1841: "The Eastern Ghilzyes are kicking up a row about some deductions which have been made from their pay. The rascals have completely succeeded in cutting communications for the time being, which is very provoking to me at this time; but they will be well trounced for their pains. One down, t'other come on, is the principle of these vagabonds".[52]

Macnaughten ordered an expedition. On 10 October 1841, the Ghazis in a night raid defeated the Thirty-fifth Native Infantry, but were defeated the next day by the Thirteenth Light Infantry.[52] After their defeat, which led to the rebels fleeing to the mountains, Macnaughten overplayed his hand by demanding that the chiefs who rebelled now send their children to Shuja's court as hostages to prevent another rebellion.[53] As Shuja had a habit of mutilating people who displeased him in the slightest, Macnaghten's demand that the children of the chiefs go to the Emir's court was received with horror, which led the Ghazi chiefs to vow to fight on. Macnaghten who just been appointed the governor of Bombay was torn between a desire to leave Afghanistan on a high note with country settled and peaceful vs. a desire to crush the Ghazis, which lead him to temporize, at one moment threatening the harshest reprisals and the next moment, compromising by abandoning his demand for hostages.[54] Macnaghten's alternating policy of confrontation and compromise was perceived as weakness, which encouraged the chiefs around Kabul to start rebelling.[55] Shuja was so unpopular that many of his ministers and the Durrani clan joined the rebellion[56]

On the night of 1 November 1841, a group of Afghan chiefs met at the Kabul house of one of their number to plan the uprising, which began in the morning of the next day.[52] In a flammable situation, the spark was provided unintentionally by Burnes. A Kashmiri slave girl who belonged to a Pashtun chief Abdullah Khan Achakzai living in Kabul ran away to Burnes's house. When Ackakzai sent his retainers to retrieve her, it was discovered that Burnes had taken the slave girl to his bed, and he had one of Azkakzai's men beaten.[57] A secret jirga (council) of Pashtun chiefs was held to discuss this violation of pashtunwali, where Ackakzai holding a Koran in one hand stated: "Now we are justified in throwing this English yoke; they stretch the hand of tyranny to dishonor private citizens great and small: fucking a slave girl isn't worth the ritual bath that follows it: but we have to put a stop right here and now, otherwise these English will ride the donkey of their desires into the field of stupidity, to the point of having all of us arrested and deported to a foreign field".[57] At the end of his speech, all of the chiefs shouted "Jihad".[57]

Lady Sale wrote in her diary on 2 November 1841: "This morning early, all was in commotion in Kabul. The shops were plundered and the people all fighting."[58] That same day, a mob "thirsting for blood" appeared outside of the house of the East India Company's second political officer, Sir Alexander 'Sekundar' Burnes, where Burnes ordered his sepoy guards not to fire while he stood outside haranguing the mob in Pashto, attempting unconvincingly to persuade the assembled men that he did not bed their daughters and sisters.[59] Captain William Broadfoot who was with Burnes saw the mob march forward, leading him to open fire with another officer writing in his diary that he "killed five or six men with his own hand before he was shot down".[59] The mob smashed in to Burnes's house, where he, his brother Charles, their wives and children, several aides and the sepoys were all torn to pieces.[59] The mob then attacked the home of the paymaster Johnston who was not present, leading to later write when he surveyed the remains of his house that they "gained possession of my treasury by undermining the wall...They murdered the whole of the guard (one officer and 28 sepoys), all my servants (male, female, and children), plundered the treasury...burnt all my office records...and possessed themselves of all my private property".[59] The British forces took no action in response despite being only five minutes away, which encouraged further revolt.[59] The only person who took action that day was Shuja who ordered out one of his regiments from the Bala Hissar commanded by a Scots mercenary named Campbell to crush the riot, but the old city of Kabul with its narrow, twisting streets favored the defensive with Campbell's men coming under fire from rebels in the houses above.[60] After losing about 200 men killed, Campbell retreated back to the Bala Hissar.[61] After hearing of the defeat of his regiment, Shuja descended into what Kaye called "a pitiable state of dejection and alarm", sinking into a deep state of depression as it finally dawned on him that his people hated him and wanted to see him dead.[61] Captain Sturt was sent to the Bala Hissar by Elphinstone to see if it were possible to recover control of the city later that afternoon, where his mother-in-law Lady Sale noted in her diary: "Just as he entered the precincts of the palace, he was stabbed in three places by a young man well dressed, who escaped into a building close-by, where he was protected by the gates being shut."[61] Sturt was sent home to be cared for by Lady Sale and his wife with the former noting: "He was covered with blood issuing from his mouth and was unable to articulate. He could not lie down, from the blood choking him", only being capable hours later to utter one word: "bet-ter".[61] Lady Sale was highly critical of Elphinstone's leadership, writing: "General Elphinstone vacillates on every point. His own judgement appears to be good, but he is swayed by the last speaker", criticising him for "...a very strange circumstance that troops were not immediately sent into the city to quell the affair in the commencement, but we seem to sit quietly with our hands folded, and look on".."[61] Despite both being in the cantonment, Elphinstone prefer to write letters to Macnaughten, with one letter on 2 November saying "I have been considering what can done tomorrow" (he decided to do nothing that day), stating "our dilemma is a difficult one", and finally concluding "We must see what the morning brings".[62] The British situation soon deteriorated when Afghans stormed the poorly defended supply fort inside Kabul on 9 November.

In the following weeks the British commanders tried to negotiate with Akbar Khan. Macnaghten secretly offered to make Akbar Afghanistan's vizier in exchange for allowing the British to stay, while simultaneously disbursing large sums of money to have him assassinated, which was reported to Akbar Khan. A meeting for direct negotiations between Macnaghten and Akbar was held near the cantonment on 23 December, but Macnaghten and the three officers accompanying him were seized and slain by Akbar Khan. Macnaghten's body was dragged through the streets of Kabul and displayed in the bazaar. Elphinstone had partly lost command of his troops already and his authority was badly damaged.

Destruction of Elphinstone's army

On 1 January 1842, following some unusual thinking by Elphinstone, which may have had something to do with the poor defensibility of the cantonment, an agreement was reached that provided for the safe exodus of the British garrison and its dependents from Afghanistan.[63] Five days later, the withdrawal began. The departing British contingent numbered around 16,500, of which about 4,500 were military personnel, and over 12,000 were camp followers. Many of the camp followers were Afghan women who had taken British lovers and knew that they would be killed by their vengeful menfolk for having "shamed" their families. Lieutenant Eyre commented about the camp followers that "These proved from the very first mile a serious clog on our movements".[64] Lady Sale brought with her 40 servants, none of whom she named in her diary while Lieutenant Eyre's son was saved by a female Afghan servant, who rode through an ambush with the boy on her back, but he never gave her name.[64] The American historian James Perry noted: "Reading the old diaries and journals, it is almost as if these twelve thousand native servants and sepoy wives and children didn't exist individually. In a way, they really didn't. They would die, all of them-shot, stabbed, frozen to death-in these mountain passes, and no one bothered to write down the name of even one of them".[64] The military force consisted mostly of Indian units and one British battalion, 44th Regiment of Foot.

They were attacked by Pakhtuns as they struggled through the snowbound passes. On the first day, the retreating force made only five miles and as Lady Sale wrote about their arrival at a village of Begramee: "There were no tents, save two or three small palls that arrived. Everyone scraped away the snow as best they might, to make a place to lie down. The evening and night were intensely cold; no food for man or beast procurable, except a few handful of bhoosay [chopped stew], for which we had to pay five to ten rupees".[65] As the night fell and with it the temperatures dropped well below freezing, the retreating force learned that they lost all of their supplies of food and their baggage.[66] On the second day all of the men of the Royal Afghan Army's 6th regiment deserted, heading back to Kabul, marking the end of the first attempt to give Afghanistan a national army.[65] For several months afterwards, what had once been Shuja's army was reduced to begging on the streets of Kabul as Akbar had of all of Shuja's mercenaries mutilated before throwing them on the streets to beg.[67] Despite Akbar Khan's promise of safe conduct, the Anglo-Indian force was repeatedly attack by the Ghilzais, with one especially fierce Afghan attack being beaten off with a spirited bayonet charge by the 44th Foot.[65]

While trying to cross the Koord-Kabual pass in the Hindu Kush that was described as five miles long and "so narrow and so shut in on either side that the wintry sun rarely penetrates its gloomy recesses", the Anglo-Indian force was ambushed by the Ghilzai tribesmen.[68] Johnson described "murderous fire" that forced the British to abandon all baggage while camp followers regardless of sex and age were cut down with swords.[69] Lady Sale wrote: "Bullets kept whizzing by us" while some of the artillerymen smashed open the regimental store of brandy to get drunk amid the Afghan attacks.[68] Lady Sale wrote she drank a tumbler of sherry "which at any other time would have made me very unlady-like, but now merely warmed me."[68] Lady Sale took a bullet in her wrist while she had to watch as her son-in-law Sturt had "...his horse was shot out from him and before he could rise from the ground he received a severe wound in the abdomen".[68] With his wife and mother-in-law by his side in the snow, Sturt bled to death over the course of the night.[68] The gentle, kindly, but naive and gullible Elphinstone continued to believe that Akbar Khan was his "ally", and believed his promise that he would send out the captured supplies if he stopped the retreat on 8 January.[70] Adding to the misery of the British, that night a ferocious blizzard blew in, causing hundreds to freeze to death.[71]

On 9 January 1842, Akbar sent out a messenger saying he was willing to take all of the British women as hostages, giving his word that they would not be harmed, and said that otherwise his tribesmen would show no mercy and kill all the women and children.[68] One of the British officers sent to negotiate with Akbar heard him say to his tribesmen in Dari (Afghan Farsi) – a language spoken by many British officers – to "spare" the British while saying in Pashto, which most British officers did not speak, to "slay them all".[72] Lady Sale, her pregnant daughter Alexandria and the rest of British women and children accepted Akbar's offer of safe conduct back to Kabul.[68] As the East India Company would not pay a ransom for Indian women and children, Akbar refused to accept them, and so the Indian women and children died with the rest of the force in the Hindu Kush.[70] The camp followers captured by the Afghans were stripped of all their clothing and left to freeze to death in the snow.[73] Lady Sale wrote that as she was taken back to Kabul she noticed: "The road was covered with awful mangled bodies, all naked".[74]

In the early morning of 10 January, the column resumed its march, with everyone tired, hungry and cold.[70] Most of the sepoys by this time had lost a finger or two to frostbite, and could not fire their guns.[75] At the narrow pass of Tunghee Tareekee, which was 50 yards long, and only 4 yards wide, the Ghizye tribesmen ambushed the column, killing without mercy all of the camp followers. The Anglo-Indian soldiers fought their way over the corpses of the camp followers with heavy losses to themselves.[70] From a hill, Akbar Khan and his chiefs watched the slaughter while sitting on their horses, being apparently very much amused by the carnage.[70] Captain Shelton and a few soldiers from the 44th regiment held the rear of the column and fought off successive Afghan attacks, despite being outnumbered.[70] Johnson described Shelton as fighting like a "bulldog" with his sword, cutting down any Afghan who tried to take him on so efficiently that by the end of the day no Afghan would challenge him.[76] On the evening of 11 January 1842, General Elphinstone, Captain Shelton, the paymaster Johnston, and Captain Skinner met with Akbar Khan to ask him to stop his attacks on the column.[77] Akbar Khan provided them with warm tea and a fine meal before telling them that they were all now his hostages as he reckoned the East India Company would pay good ransoms for their freedom, and when Captain Skinner tried to resist, he was shot in the face.[77] Command now fell to Brigadier Thomas Anquetil.[77]

The evacuees were killed in huge numbers as they made their way down the 30 miles (48 km) of treacherous gorges and passes lying along the Kabul River between Kabul and Gandamak, and were massacred at the Gandamak pass before a survivor reached the besieged garrison at Jalalabad. At Gandamak, some 20 officers and 45 other ranks of the 44th Foot regiment, together with some artillerymen and sepoys, armed with some 20 muskets and two rounds of ammunition to every man, found themselves at dawn surrounded by Afghan tribesmen.[78] The force had been reduced to fewer than forty men by a withdrawal from Kabul that had become, towards the end, a running battle through two feet of snow. The ground was frozen, the men had no shelter and had little food for weeks. Of the weapons remaining to the survivors at Gandamak, there were approximately a dozen working muskets, the officers' pistols and a few swords. The British formed a square and defeated the first couple of the Afghan attacks, "driving the Afghans several times down the hill" before running out of ammunition. They then fought on with their bayonets and swords before being overwhelmed.[78] The Afghans took only 9 prisoners and killed the rest.[79] The remnants of the 44th were all killed except Captain James Souter, Sergeant Fair and seven soldiers who were taken prisoner.[80] The only soldier to reach Jalalabad was Dr. William Brydon and several sepoys over the following nights. Another source states that over one hundred British were taken prisoner.[81]

Many of the women and children were taken captive by the Afghan warring tribes; some of these women married their captors (one such lady was the wife of Captain Warburton). Children taken from the battlefield at the time who were later identified in the early part of the 20th century to be those of the fallen soldiers were brought up by Afghan families as their own children.[82][83][84][85][86]

Reprisals

At the same time as the attacks on the garrison at Kabul, Afghan forces beleaguered the other British contingents in Afghanistan. These were at Kandahar (where the largest British force in the country had been stationed), Jalalabad (held by a force which had been sent from Kabul in October 1841 as the first stage of a planned withdrawal) and Ghazni. Ghazni was stormed, but the other garrisons held out until relief forces arrived from India, in spring 1842. Akbar Khan was defeated near Jalalabad and plans were laid for the recapture of Kabul and the restoration of British hegemony.

However, Lord Auckland had suffered a stroke and had been replaced as governor-general by Lord Ellenborough, who was under instructions to bring the war to an end following a change of government in Britain. Ellenborough ordered the forces at Kandahar and Jalalabad to leave Afghanistan after inflicting reprisals and securing the release of prisoners taken during the retreat from Kabul.

In August 1842 General Nott advanced from Kandahar, pillaging the countryside and seizing Ghazni, whose fortifications he demolished. Meanwhile, General Pollock, who had taken command of a demoralized force in Peshawar used it to clear the Khyber Pass to arrive at Jalalabad, where General Sale had already lifted the siege. From Jalalabad, General Pollock inflicted a further crushing defeat on Akbar Khan. The combined British forces defeated all opposition before taking Kabul in September. A month later, having rescued the prisoners and demolished the city's main bazaar as an act of retaliation for the destruction of Elphinstone's column, they withdrew from Afghanistan through the Khyber Pass. Dost Muhammad was released and re-established his authority in Kabul. He died on 9 June 1863. Dost Mohammad is reported to have said:

I have been struck by the magnitude of your resources, your ships, your arsenals, but what I cannot understand is why the rulers of so vast and flourishing an empire should have gone across the Indus to deprive me of my poor and barren country.[81]

Legacy

Many voices in Britain, from Lord Aberdeen[87] to Benjamin Disraeli, had criticized the war as rash and insensate. The perceived threat from Russia was vastly exaggerated, given the distances, the almost impassable mountain barriers, and logistical problems that an invasion would have to solve. In the three decades after the First Anglo-Afghan War, the Russians did advance steadily southward towards Afghanistan. In 1842 the Russian border was on the other side of the Aral Sea from Afghanistan; but five years later the tsar's outposts had moved to the lower reaches of the Amu Darya. By 1865 Tashkent had been formally annexed, as was Samarkand three years later. A peace treaty in 1873 with Amir Alim Khan of the Manghit Dynasty, the ruler of Bukhara, virtually stripped him of his independence. Russian control then extended as far as the northern bank of the Amu Darya.

In 1878, the British invaded again, beginning the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

Lady Butler's famous painting of Dr. William Brydon, initially thought to be the sole survivor, gasping his way to the British outpost in Jalalabad, helped make Afghanistan's reputation as a graveyard for foreign armies and became one of the great epics of empire.

In 1843 British army chaplain G.R. Gleig wrote a memoir of the disastrous (First) Anglo-Afghan War, of which he was one of the very few survivors. He wrote that it was

a war begun for no wise purpose, carried on with a strange mixture of rashness and timidity, brought to a close after suffering and disaster, without much glory attached either to the government which directed, or the great body of troops which waged it. Not one benefit, political or military, was acquired with this war. Our eventual evacuation of the country resembled the retreat of an army defeated”.[88]

The Church of St. John the Evangelist located in Navy Nagar, Mumbai, India, more commonly known as the Afghan Church, was dedicated in 1852 as a memorial to the dead of the conflict.

Battle honour

The battle honour of 'Afghanistan 1839' was awarded to all units of the presidency armies of the East India Company that had proceeded beyond the Bolan Pass, by gazette of the governor-general, dated 19 November 1839, the spelling changed from 'Afghanistan' to 'Affghanistan' by Gazette of India No. 1079 of 1916, and the date added in 1914. All the honours awarded for this war are considered to be non-repugnant. The units awarded this battle honour were:

- 4th Bengal Irregular Cavalry – 1 Horse

- 5th Madras Infantry

- Poona Auxiliary Horse – Poona Horse

- Bombay Sappers & Miners – Bombay Engineer Group

- 31st Bengal Infantry

- 43rd Bengal Infantry

- 19th Bombay Infantry

- 1st Bombay Cavalry – 13th Lancers

- 2nd, 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry – mutinied in 1857

- 2nd, 3rd Companies of Bengal Sappers and Miners – mutinied in 1857

- 16th, 35th, 37th, 48th Bengal Infantry – mutinied in 1857

- 42nd Bengal Infantry (5th LI) – disbanded 1922

Fictional depictions

- The First Anglo–Afghan war is depicted in a work of historical fiction, Flashman by George MacDonald Fraser. (This is Fraser's first Flashman novel.)

- The ordeal of Dr. Brydon may have influenced the story of Dr. John Watson in Sherlock Holmes, although his wound was suffered in the second war.

- Emma Drummond's novel Beyond all Frontiers (1983) is based on these events, as are Philip Hensher's Mulberry Empire (2002) and Fanfare (1993), by Andrew MacAllan, a distant relation of Dr William Brydon.

- G.A. Henty's children's novel To Herat and Kabul focuses on the Anglo-Afghan War through the perspective of a Scottish expatriate teenager named Angus. Theodor Fontane's poem, Das Trauerspiel von Afghanistan (The Tragedy of Afghanistan) also refers to the massacre of Elphinstone’s army.[89]

See also

- Military history of Britain

- Military history of Afghanistan

- Chapslee Estate

- European influence in Afghanistan

- Invasions of Afghanistan

- Second Anglo-Afghan War

- Third Anglo-Afghan War

- War artist James Rattray

References

- Kohn, George Childs (2013). Dictionary of Wars. Revised Edition. London/New York: Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 9781135954949.

- Baxter, Craig. "The First Anglo–Afghan War". In Federal Research Division, Library of Congress (ed.). Afghanistan: A Country Study. Baton Rouge, LA: Claitor's Pub. Division. ISBN 1-57980-744-5. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Antoinette Burton, "On the First Anglo-Afghan War, 1839–42: Spectacle of Disaster"

- Keay, John (2010). India: A History (revised ed.). New York, NY: Grove Press. pp. 418–19. ISBN 978-0-8021-4558-1.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 110.

- Fromkin, David "The Great Game in Asia" pp. 936–51 from Foreign Affairs, Volume 58, Issue 4, Spring 1980 pp. 937–38

- Fromkin, David "The Great Game in Asia" pp. 936–51 from Foreign Affairs, Volume 58, Issue 4, Spring 1980 p. 938

- Eskridge-Kosmach, Alena "The Russian Press and the Ideas of Russia’s ‘Special Mission in the East’ and ‘Yellow Peril’" pp. 661–75 from Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Volume 27, November 2014 pp. 661–62.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas Nicholas I and Official Nationality in Russia, 1825–1855, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1959 p. 255.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas Nicholas I and Official Nationality in Russia, 1825–1855, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1959 pp. 257–58.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas Nicholas I and Official Nationality in Russia, 1825–1855, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1959 p. 258.

- L. W. Adamec/J. A. Norris, Anglo-Afghan Wars, in Encyclopædia Iranica, online ed., 2010

- J.A. Norris, Anglo-Afghan Relations Archived 2013-05-17 at the Wayback Machine, in Encyclopædia Iranica, online ed., 2010

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 111.

- Macintyre, Ben The Man Who Would Be King, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2002 p. 205

- Macintyre, Ben The Man Who Would Be King, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2002 pp. 205–06

- Macintyre, Ben The Man Who Would Be King, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2002 p. 206

- Macintyre, Ben The Man Who Would Be King, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2002 pp. 206–07

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 pp. 110–11.

- Macintyre, Ben The Man Who Would Be King, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2002 p. 32

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 112.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 pp. 109–10.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 pp. 112–13.

- "The Company That Ruled The Waves". The Economist. 17 December 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 113.

- Ram, Subedar Sita. From Sepoy to Subedar. p. 86. ISBN 0-333-45672-6.

- Yapp, M.E. Journal Article The Revolutions of 1841–2 in Afghanistan pp. 333–81 from The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 27, Issue 2, 1964 p. 338.

- Ewans, Martin (2002). Afghanistan: A Short History of Its People and Politics. HarperCollins. p. 63. ISBN 0060505087.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 page 116.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 117.

- Forbes, Archibald (2014). "The Afghan Wars 1839-42 and 1878-80". Project Gutenberg EBook. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 121.

- Holdsworth, T W E (1840). Campaign of the Indus: In a Series of Letters from an Officer of the Bombay Division. Private Copy. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 120.

- Dupree, L. Afghanistan. Princeton: Princeton Legacy Library, 1980. p. 379

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 pp. 120–21

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 123

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 123.

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 p. 223.

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 pp. 223–24.

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 pp. 223–25.

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 pp. 224–25.

- Yapp, M.E. Journal Article The Revolutions of 1841–2 in Afghanistan pp. 333–81 from The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 27, Issue 2, 1964 p. 338.

- Yapp, M.E. "The Revolutions of 1841–2 in Afghanistan" pp. 333–81 from The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 27, Issue 2, 1964 pp. 339–40.

- Yapp, M.E "British Perceptions of the Russian Threat to India" pp. 647–65 from Modern Asian Studies, Volume 21, No. 4 1987 p. 656.

- Yapp, M.E "British Perceptions of the Russian Threat to India" pp. 647–65 from Modern Asian Studies, Volume 21, No. 4 1987 p. 659.

- Yapp, M.E "British Perceptions of the Russian Threat to India" pp. 647–65 from Modern Asian Studies, Volume 21, No. 4 1987 p. 660.

- David, Saul. Victoria's Wars, 2007 Penguin Books. p. 41

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 124

- Who after his demise in 1841, was replaced by his son Mir Aqa Jan, see Maj (r) Nur Muhammad Shah, Kohistani, Nur i Kohistan, Lahore, 1957, pp. 49–52

- Yapp, M.E. "The Revolutions of 1841–2 in Afghanistan" pp. 333–81 from The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 27, Issue 2, 1964 pp. 334–35.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 125.

- Yapp, M.E. "The Revolutions of 1841–2 in Afghanistan" pp 333–81 from The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 27, Issue 2, 1964 p. 335.

- Yapp, M.E. "The Revolutions of 1841–2 in Afghanistan" pp. 333–81 from The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 27, Issue 2, 1964 p. 336.

- Yapp, M.E. : "The Revolutions of 1841–2 in Afghanistan" pp. 333–81 from The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 27, Issue 2, 1964 p. 336.

- Yapp, M.E. "The Revolutions of 1841–2 in Afghanistan" pp. 333–81 from The Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 27, Issue 2, 1964 p. 336.

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 p. 292.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 pp. 125–26.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 126.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 pp. 126–27.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 127.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 128.

- Macrory, Patrick. "Retreat From Kabul: The Catastrophic Defeat In Afghanistan, 1842". 2002 The Lyons Press p. 203

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 133.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 134.

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 pp. 366–67

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 p. 369.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 135.

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 p. 373

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 136.

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 p. 375

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 p. 374

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 pp. 383–84

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 p. 384

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 p. 379

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 p. 380.

- Perry, James Arrogant Armies, Edison: CastleBooks, 2005 p. 137.

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 p. 385

- Dalrymple, William Return of a King, London: Bloomsbury, 2012 pages 385

- Blackburn, Terence R. (2008). The extermination of a British army: the retreat from Cabul. New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. p. 121

- Ewans, Martin (2002). Afghanistan: A Short History of Its People and Politics. HarperCollins. p. 70. ISBN 0060505087.

- Shultz, Richard H.; Dew, Andrea J. (22 August 2006). Insurgents, Terrorists, and Militias: The Warriors of Contemporary Combat. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231503426.

- Toorn, Wout van der (17 March 2015). Logbook of the Low Countries (in Arabic). Page Publishing Inc. ISBN 9781634179997.

- Henshall, Kenneth (13 March 2012). A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230369184.

- Little, David; Understanding, Tanenbaum Center for Interreligious (8 January 2007). Peacemakers in Action: Profiles of Religion in Conflict Resolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521853583.

- Steele, Jonathan (1 January 2011). Ghosts of Afghanistan: Hard Truths and Foreign Myths. Counterpoint Press. p. 110. ISBN 9781582437873.

- 'no man could say, unless it were subsequently explained, this course was not as rash and impolitic, as it was ill-considered, oppressive, and unjust.' Hansard, 19 March 1839.

- Gleig, George R. Sale's Brigade In Afghanistan, John Murray, 1879, p. 181.

- The Tragedy of Afghanistan, Retrieved 2013-08-21.

Further reading

- Dalrymple, William, (2012) Return of a King: the battle for Afghanistan, London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781408818305

- Findlay, Adam George (2015). Preventing Strategic Defeat: A Reassessment of the First Anglo-Afghan War (PhD thesis). University of Wollongong.

- Fowler, Corinne, (2007) Chasing Tales: Travel Writing, Journalism and the History of British Ideas about Afghanistan, Amsterdam: Rodopi, ISBN 9789042022621

- Greenwood, Joseph, (1844) Narrative of the Late Victorious Campaign in Affghanistan, under General Pollock: With Recollections of Seven Years' service in India. London: H. Colburn

- Hopkirk, Peter, (1992) The Great Game, New York, NY: Kodansha America, ISBN 1-56836-022-3

- Husain, Farrukh (2018) Afghanistan in the age of empires - the great game for South and Central Asia' London: Silk Road Books and photos. (ISBN 978-1-5272-1633-4)

- Kaye, Sir John, (1860) History of the First Afghan War, London.

- Macrory, Patrick, (1966) The Fierce Pawns, J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia

- Macrory, Patrick, (2002) Retreat from Kabul: The Catastrophic British Defeat in Afghanistan, 1842. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-59921-177-0

- Morris, Mowbray. The First Afghan War. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington (1878).

- Perry, James M., (1996), Arrogant Armies: Great Military Disasters and the Generals Behind Them. New York:Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-11976-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Anglo-Afghan War. |

- First Afghan War (Battle of Ghuznee)

- First Afghan War (Battle of Kabul 1842)

- The Siege of Jellalabad

- First Afghan War (Battle of Kabul and retreat to Gandamak)

- The Afghan Wars 1839–42 and 1878–80 by Archibald Forbes, from Project Gutenberg

- Pictures of the First Anglo–Afghan War

- The War of Kabul and Kandahar, circa 1850