Cape Colony

The Cape of Good Hope, also known as the Cape Colony (Dutch: Kaapkolonie), was a British colony in present-day South Africa, named after the Cape of Good Hope. The British colony was preceded by an earlier Dutch colony of the same name, the Kaap de Goede Hoop, established in 1652 by the Dutch East India Company. The Cape was under Dutch rule from 1652 to 1795 and again from 1803 to 1806.[5] The Dutch lost the colony to Great Britain following the 1795 Battle of Muizenberg, but had it returned following the 1802 Peace of Amiens. It was re-occupied by the UK following the Battle of Blaauwberg in 1806, and British possession affirmed with the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814.

Cape of Good Hope Kaap de Goede Hoop (Dutch) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1806–1910 | |||||||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||

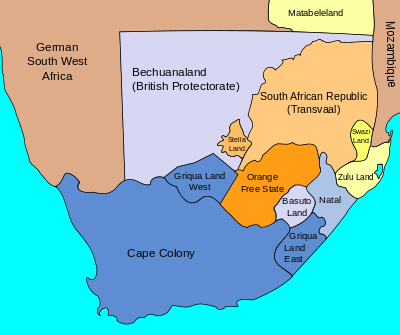

The Cape of Good Hope c. 1890 with Griqualand East and Griqualand West annexed and Stellaland/Goshen (light red) claimed | |||||||||||||

| Status | British colony | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Cape Town | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | English, Dutch (official¹) Khoekhoe, Xhosa also spoken | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Dutch Reformed Church, Anglican, San religion | ||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King/Queen | |||||||||||||

• 1795–1820 | George III | ||||||||||||

• 1820–1830 | George IV | ||||||||||||

• 1830–1837 | William IV | ||||||||||||

• 1837–1901 | Victoria | ||||||||||||

• 1901–1910 | Edward VII | ||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||

• 1797–1798 | George Macartney | ||||||||||||

• 1901–1910 | Walter Hely-Hutchinson | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||

• 1872–1878 | John Charles Molteno | ||||||||||||

• 1908–1910 | John X. Merriman | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Imperialism | ||||||||||||

• Established | 1806 | ||||||||||||

| 1803–1806 | |||||||||||||

| 1814 | |||||||||||||

| 1844 | |||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1910 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1822[1] | 331,900 km2 (128,100 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| 1910 | 569,020 km2 (219,700 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1822[1] | 110,380 | ||||||||||||

• 1865 census[2] | 496,381 | ||||||||||||

• 1910 | 2,564,965 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Pound sterling | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

¹ Dutch was the sole official language until 1822, when the British officially replaced Dutch with English.[3] Dutch was reincluded as a second official language in 1882. 2 Penguin Islands and Walvis Bay 3 Basutoland was annexed to the Cape Colony in 1871, before becoming a Crown colony in 1884.[4] | |||||||||||||

| Historical states in present-day South Africa |

|---|

|

|

before 1600

|

|

1600–1700

|

|

1700–1800

|

|

1800–1850

|

|

1850–1875

|

|

1875–1900

|

|

1900–present

|

|

|

The Cape of Good Hope then remained in the British Empire, becoming self-governing in 1872, and uniting with three other colonies to form the Union of South Africa in 1910. It then was renamed the Province of the Cape of Good Hope.[6] South Africa became a sovereign state in 1931 by the Statute of Westminster. In 1961 it became the Republic of South Africa and obtained its own monetary unit called the Rand. Following the 1994 creation of the present-day South African provinces, the Cape Province was partitioned into the Eastern Cape, Northern Cape, and Western Cape, with smaller parts in North West province.

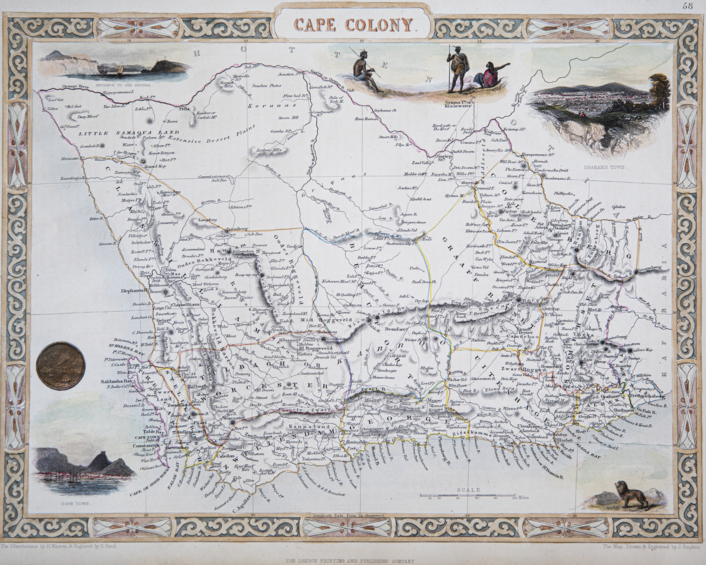

The Cape of Good Hope was coextensive with the later Cape Province, stretching from the Atlantic coast inland and eastward along the southern coast, constituting about half of modern South Africa: the final eastern boundary, after several wars against the Xhosa, stood at the Fish River. In the north, the Orange River, also known as the Gariep River, served as the boundary for some time, although some land between the river and the southern boundary of Botswana was later added to it. From 1878, the colony also included the enclave of Walvis Bay and the Penguin Islands, both in what is now Namibia.

History

Dutch settlement

An expedition of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) led by Jan van Riebeeck established a trading post and naval victualing station at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.[7] Van Riebeeck's objective was to secure a harbour of refuge for Dutch ships during the long voyages between Europe and Asia.[7] Within about three decades, the Cape had become home to a large community of "vrijlieden", also known as "vrijburgers" (free citizens), former VOC employees who settled in Dutch colonies overseas after completing their service contracts.[8] Vrijburgers were mostly married Dutch citizens who undertook to spend at least twenty years farming the land within the fledgling colony's borders; in exchange they received tax exempt status and were loaned tools and seeds.[9] Reflecting the multi-national nature of the early trading companies, the Dutch also granted vrijburger status to a number of former Scandinavian and German employees as well.[10] In 1688 they also sponsored the immigration of nearly two hundred French Huguenot refugees who had fled to the Netherlands upon the Edict of Fontainebleau.[11] There was a degree of cultural assimilation due to intermarriage, and the almost universal adoption of the Dutch language.[12]

Many of the colonists who settled directly on the frontier became increasingly independent and localised in their loyalties.[13] Known as Boers, they migrated westwards beyond the Cape Colony's initial borders and had soon penetrated almost a thousand kilometres inland.[14] Some Boers even adopted a nomadic lifestyle permanently and were denoted as trekboers.[15] The Dutch colonial period was marred by a number of bitter conflicts between the colonists and the Khoisan, followed by the Xhosa, both of which they perceived as unwanted competitors for prime farmland.[15]

Dutch traders imported thousands of slaves to the Cape of Good Hope from the Dutch East Indies and other parts of Africa.[16] By the end of the eighteenth century the Cape's population swelled to about 26,000 people of European descent and 30,000 slaves.[17][18]

British conquest

In 1795, France occupied the Seven Provinces of the Netherlands, the mother country of the Dutch East India Company. This prompted Great Britain to occupy the territory in 1795 as a way to better control the seas in order to stop any potential French attempt to reach India. The British sent a fleet of nine warships which anchored at Simon's Town and, following the defeat of the Dutch militia at the Battle of Muizenberg, took control of the territory. The Dutch East India Company transferred its territories and claims to the Batavian Republic (the Revolutionary period Dutch state) in 1798, and went bankrupt in 1799. Improving relations between Britain and Napoleonic France, and its vassal state the Batavian Republic, led the British to hand the Cape of Good Hope over to the Batavian Republic in 1803, under the terms of the Treaty of Amiens.

| Part of a series on |

| Cape Colony history |

|---|

In 1806, the Cape, now nominally controlled by the Batavian Republic, was occupied again by the British after their victory in the Battle of Blaauwberg. The temporary peace between the UK and Napoleonic France had crumbled into open hostilities, whilst Napoleon had been strengthening his influence on the Batavian Republic (which Napoleon would subsequently abolish later the same year). The British, who set up a colony on 8 January 1806, hoped to keep Napoleon out of the Cape, and to control the Far East trade routes.

The Cape Colony at the time of British occupation was three months’ sailing distance from London. The white colonial population was small, no more than 25,000 in all, scattered across a territory of 100,000 square miles. Most lived in Cape Town and the surrounding farming districts of the Boland, an area favoured with rich soils, a Mediterranean climate and reliable rainfall. Cape Town had a population of 16,000 people. [19] In 1814 the Dutch government formally ceded sovereignty over the Cape to the British, under the terms of the Convention of London.

British colonisation

The British started to settle the eastern border of the colony, with the arrival in Port Elizabeth of the 1820 Settlers. They also began to introduce the first rudimentary rights for the Cape's black African population and, in 1834, abolished slavery. The resentment that the Dutch farmers felt against this social change, as well as the imposition of English language and culture, caused them to trek inland en masse. This was known as the Great Trek, and the migrating Boers settled inland, forming the Boer republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State.

British immigration continued in the Cape, even as many of the Boers continued to trek inland, and the ending of the British East India Company's monopoly on trade led to economic growth. At the same time, the long series of border wars fought against the Xhosa people of the Cape's eastern frontier finally died down when the Xhosa took part in a mass destruction of their own crops and cattle, in the belief that this would cause their spirits to appear and defeat the whites. The resulting famine crippled Xhosa resistance and ushered in a long period of stability on the border.

Peace and prosperity led to a desire for political independence. In 1853, the Cape Colony became a British Crown colony with representative government.[20] In 1854, the Cape of Good Hope elected its first parliament, on the basis of the multi-racial Cape Qualified Franchise. Cape residents qualified as voters based on a universal minimum level of property ownership, regardless of race.

The fact that executive power remained completely in the authority of the British governor did not relieve tensions in the colony between its eastern and western sections.[21]

Responsible government

In 1872, after a long political battle, the Cape of Good Hope achieved responsible government under its first Prime Minister, John Molteno. Henceforth, an elected Prime Minister and his cabinet had total responsibility for the affairs of the country. A period of strong economic growth and social development ensued, and the eastern-western division was largely laid to rest. The system of multi-racial franchise also began a slow and fragile growth in political inclusiveness, and ethnic tensions subsided.[22] In 1877, the state expanded by annexing Griqualand West and Griqualand East[23] – that is, the Mount Currie district (Kokstad). The emergence of two Boer mini-republics along the Missionary Road resulted in 1885 in the Warren Expedition, sent to annex the republics of Stellaland and Goshen. Major-General Charles Warren annexed the land south of the (usually dry) Molopo River as the colony of British Bechuanaland and proclaimed a protectorate over the land lying to its north. Vryburg, the capital of Stellaland, became capital of British Bechuanaland, while Mafeking (now Mahikeng), although situated south of the protectorate border, became the protectorate's administrative centre. The border between the protectorate and the colony ran along the Molopo and Nossob rivers. In 1895 British Bechuanaland became part of the Cape Colony.

However, the discovery of diamonds around Kimberley and gold in the Transvaal led to a return to instability, particularly because they fuelled the rise to power of the ambitious imperialist Cecil Rhodes. On becoming the Cape's Prime Minister in 1890, he instigated a rapid expansion of British influence into the hinterland. In particular, he sought to engineer the conquest of the Transvaal, and although his ill-fated Jameson Raid failed and brought down his government, it led to the Second Boer War and British conquest at the turn of the century. The politics of the colony consequently came to be increasingly dominated by tensions between the British colonists and the Boers. Rhodes also brought in the first formal restrictions on the political rights of the Cape of Good Hope's black African citizens.[24]

The Cape of Good Hope remained nominally under British rule until the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, when it became the Province of the Cape of Good Hope, better known as the Cape Province.

Governors

Districts

The districts of the colony in 1850 were:

- Clanwilliam

- The Cape

- Stellenbosch

- Zwellendam

- Tulbagh/Worcester

- Beaufort

- George

- Uitenhague

- Albany

- Victoria

- Somerset

- Graaf Reynet

- Colesberg

Demographics

1904 Census

Population Figures for the 1904 Census. Source:[25]

| Population group | Number | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Black | 1,424,787 | 59.12 |

| White | 579,741 | 24.05 |

| Coloured | 395,034 | 16.39 |

| Asian | 10,242 | 0.42 |

| Total | 2,409,804 | 100.00 |

See also

References

- Wilmot, Alexander; Chase, John Centlivres (1869). History of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope: From Its Discovery to the Year 1819. J. C. Juta. pp. 268–.

- "Census of the colony of the Cape of Good Hope. 1865". HathiTrust Digital Library. p. 11. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- Farlam, Paul (2001). Palmer, Vernon (ed.). Mixed Jurisdictions Worldwide: The Third Legal Family. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 0-521-78154-X.

- "Lesotho: History". The Commonwealth. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Heese, J. A. (1971). Die Herkoms van die Afrikaner 1657 - 1867 [The Origin of the Afrikaaner 1657 - 1867] (in Afrikaans). Cape Town: A. A. Balkema. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-920429-13-3.

- Statemans Year Book, 1920, section on Cape Province

- Hunt, John (2005). Campbell, Heather-Ann (ed.). Dutch South Africa: Early Settlers at the Cape, 1652-1708. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 13–35. ISBN 978-1904744955.

- Parthesius, Robert. Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters: The Development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Shipping Network in Asia 1595-1660. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9053565179.

- Lucas, Gavin (2004). An Archaeology of Colonial Identity: Power and Material Culture in the Dwars Valley, South Africa. New York: Springer, Publishers. pp. 29–33. ISBN 978-0306485381.

- Worden 2010, pp. 94–140.

- Lambert, David (2009). The Protestant International and the Huguenot Migration to Virginia. New York: Peter Land Publishing, Incorporated. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-1433107597.

- Mbenga, Bernard; Giliomee, Hermann (2007). New History of South Africa. Cape Town: Tafelburg, Publishers. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0624043591.

- Ward, Kerry (2009). Networks of Empire: Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 322–342. ISBN 978-0-521-88586-7.

- Greaves, Adrian. The Tribe that Washed its Spears: The Zulus at War (2013 ed.). Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. pp. 36–55. ISBN 978-1629145136.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stapleton, Timothy (2010). A Military History of South Africa: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid. Santa Barbara: Praeger Security International. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-0313365898.

- Worden 2010, pp. 40–43.

- Lloyd, Trevor Owen (1997). The British Empire, 1558-1995. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 201–206. ISBN 978-0198731337.

- Entry: Cape Colony. Encyclopedia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1933. James Louis Garvin, editor.

- Meredith 2007, p. 1.

- The Kingfisher Illustrated History of the World. Italy: Kingfisher. 1993. p. 576. ISBN 9780862729530.

- Illustrated History of South Africa. The Reader’s Digest Association South Africa. 1992. ISBN 0-947008-90-X.

- Parsons, Neil, A New History of Southern Africa, Second Edition. Macmillan, London (1993)

- John Dugard: International Law, A South African Perspective. Cape Town. 2006. p.136.

- Ziegler, Philip (2008). Legacy: Cecil Rhodes, the Rhodes Trust and Rhodes Scholarships. Yale: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11835-3.

- Smuts I: The Sanguine Years 1870–1919, W.K. Hancock, Cambridge University Press, 1962, pg 219

Sources

- Beck, Roger B. (2000). The History of South Africa. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 0-313-30730-X.

- Davenport, T. R. H., and Christopher Saunders (2000). South Africa: A Modern History, 5th ed. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-23376-0.

- Elbourne, Elizabeth (2002). Blood Ground: Colonialism, Missions, and the Contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 1799–1853. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2229-8.

- Le Cordeur, Basil Alexander (1981). The War of the Axe, 1847: Correspondence between the governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Henry Pottinger, and the commander of the British forces at the Cape, Sire George Berkeley, and others. Brenthurst Press. ISBN 0-909079-14-5.

- Mabin, Alan (1983). Recession and its aftermath: The Cape Colony in the eighteen eighties. University of the Witwatersrand, African Studies Institute.

- Meredith, Martin (2007). Diamonds, Gold and War: The Making of South Africa. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-8614-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ross, Robert, and David Anderson (1999). Status and Respectability in the Cape Colony, 1750–1870 : A Tragedy of Manners. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62122-4.

- Theal, George McCall (1970). History of the Boers in South Africa; Or, the Wanderings and Wars of the Emigrant Farmers from Their Leaving the Cape Colony to the Acknowledgment of Their Independence by Great Britain. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-1661-9.

- Van Der Merwe, P.J., Roger B. Beck (1995). The Migrant Farmer in the History of the Cape Colony. Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8214-1090-3.

- Worden, Nigel, Elizabeth van Heyningen, and Vivian Bickford-Smith (1998). Cape Town: The Making of a City. Cape Town: David Philip. ISBN 0-86486-435-3

- Worden, Nigel. Slavery in Dutch South Africa (2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521152662.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cape Colony. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Cape Colony. |

.svg.png)

.svg.png)