Canada (New France)

The colony of Canada was a French colony within the larger territory of New France, first claimed in the name of the King of France in 1535 during the second voyage of Jacques Cartier, later to become largely part of the modern country of Canada.[1][2][3][4] The word "Canada" at this point referred to the territory along the Saint Lawrence River,[5] then known as the Canada river, from Grosse Island in the east to a point between Quebec and Trois-Rivières,[6] although this territory had greatly expanded by 1600. French explorations continued "unto the Countreys of Canada, Hochelaga, and Saguenay"[7] before any permanent settlements were established. Even though a permanent trading post and habitation was established at Tadoussac in 1600, at the confluence of the Saguenay and Saint Lawrence rivers, it was under a trade monopoly and thus not constituted as an official French colonial settlement.

Canada | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1535–1763 | |||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

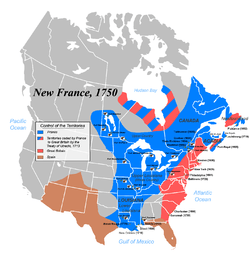

Blue: New France in 1750. Canada extended from south of the Great Lakes to the Gulf of St Lawrence. | |||||||||

| Status | Colony of France within New France | ||||||||

| Capital | Quebec | ||||||||

| Common languages | French | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• French territorial possession | 1535 | ||||||||

• Founding of Quebec | 1608 | ||||||||

• Founding of Trois-Rivières | 1634 | ||||||||

• Founding of Montreal | 1642 | ||||||||

| 1763 | |||||||||

| Currency | New France livre | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | CA | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

As a result, the first official settlement was not established within Canada until the founding of Quebec by Samuel de Champlain in 1608.[8][9] The other four colonies within New France were Hudson's Bay to the north, Acadia and Newfoundland to the east, and Louisiana far to the south.[10][11] Canada, the most developed colony of New France, was divided into three districts, Quebec, Trois-Rivières, and Montreal, each with its own government. The governor of the District of Quebec was also the governor-general of all New France.[11]

Although the terms "Canada" and "New France" are sometimes used interchangeably, "New France actually represents a much broader portion of North American territory than the Great Lakes-St Lawrence colony of Canada".[12] The Seven Years' War saw Great Britain defeat the French and their allies and take possession of Canada. In the Treaty of Paris of 1763, which formally ended the conflict, France renounced its claim to Canada in exchange for other colonies and the colony became the British colony of Quebec.[13]

Settled country

A 1740 survey of the population of the St. Lawrence River valley counted about 44,000 colonists, the majority born in Canada. Of those, 18,000 lived under the Government of Quebec, 4,000 under the Government of Trois-Rivières and 22,000 under the Government of Montreal. The population was mostly rural; Quebec had 4,600 inhabitants; Trois-Rivières had 378; and Montreal had 4,200 inhabitants. Also, Île Royale had 4,000 inhabitants (of which 1,500 were in Louisbourg), and Île Saint-Jean had 500 inhabitants. Acadia had 8,000 inhabitants.[14]

Pays d'en Haut

Dependent on Canada were the Pays d'en Haut (upper countries), a vast territory north and west of Montreal, covering the whole of the Great Lakes and stretching as far into the North American continent as the French had explored.[11] Before 1717, when it ceded territory to the new colony of Louisiana, it stretched as far south as the Illinois Country. North of the Great Lakes, a mission, Sainte-Marie among the Hurons, was established in 1639. Following the destruction of the Huron homeland in 1649 by the Iroquois, the French destroyed the mission themselves and left the area. In what are today Ontario and the eastern prairies, various trading posts and forts were built such as Fort Kaministiquia in 1679 (at modern Thunder Bay, Ontario), Fort Frontenac in 1673 (today's Kingston, Ontario), Fort Saint Pierre in 1731 (near modern Fort Frances, Ontario), Fort Saint Charles in 1732 (on Lake of the Woods located on Magnusens Island on the Northwest Angle of Minnesota) and Fort Rouillé in 1750 (today's Toronto). The mission and trading post at Sault Ste. Marie (1688) would later be split by the Canada–US border.

The French settlements in the Pays d'en Haut among and south of the Great Lakes were Fort Niagara (1678) (near modern Youngstown, New York), Fort Crevecoeur (1680) (near the present site of Creve Coeur, Illinois, a suburb of Peoria, Illinois), Fort Saint Antoine (1686) (on Lake Pepin in Wisconsin), Fort St. Joseph (1691) (on the southernmost point of St. Joseph Island, Ontario on Lake Huron), Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit (1701) (today's Detroit, Michigan), Fort Michilimackinac (1715) (on the Straits of Mackinac at Mackinaw City, Michigan), Fort Miami (1715) (modern Fort Wayne, Indiana), Fort La Baye (1717) (today's Green Bay, Wisconsin), and Fort Beauharnois (1727) (in Florence Township, Goodhue County, Minnesota).

Today, the term Les Pays-d'en-Haut refers to a regional county municipality in the Laurentides region of the present Province of Quebec, north of Montreal, while the former Pays d'en Haut was part of the District of Montreal.

Legacy

In its civil law, customs, and the cultural aspects of the majority of its population, the successor to the French colony of Canada is the Province of Quebec. The term Canada may also refer to today's Canadian federation created in 1867, or the historical Province of Canada, a British colony comprising southern Ontario and southern Quebec (referred to respectively as Upper Canada and Lower Canada when they were themselves separate British colonies prior to 1841). For Francophone Quebecers, preserving their distinctiveness from English Canada has been historically important, particularly since the rise of contemporary Quebec nationalism dating from the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s. Francophone Quebecers will therefore often use the term New France (Nouvelle-France) when referring to Canada (New France), and the term Canadien, at one time used to refer to the French-speaking populations of colonial Canada, was replaced by the term Canadien-Français (French-Canadian), and more recently by Québécois. Descendants of the original French-speaking Canadien population of Canada (New France) now living outside of Quebec are now often referred to by reference to their current province of residence, such as Franco-Ontarian. Francophone populations in the Maritime provinces apart from northwestern New Brunswick are, however, more likely to be descended from the settlers of the French colony of Acadia, and therefore still call themselves Acadians.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New France. |

References

- Lamb, W. Kaye (19 March 2018). "Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.

- Conrick, Maeve; Regan, Vera (2007). French in Canada: Language Issues. Peter Lang. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-03910-142-9.

- Rayburn, Alan (2001). Naming Canada: Stories about Canadian Place Names. University of Toronto Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8020-8293-0.

- Parkman, Francis (1996). Pioneers of France in the New World. University of Nebraska Press. p. 202. ISBN 0-8032-8744-5.

- Boswell, Randy (22 April 2013). "Putting Canada on the map". National Post.

- Cartier, Jacques (1993). Cook, Ramsay (ed.). Voyages of Jacques. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 43.

- Cartier, Jacques (1993). Cook, Ramsay (ed.). Voyages of Jacques. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 96.

- New, William H. (2002). Encyclopedia of Literature in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8020-0761-2.

- Kelley, Ninette; Trebilcock, Michael J. (2010). The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy. University of Toronto Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-8020-9536-7.

- "Canada at the Time of New France". Site for Language Management in Canada. University of Ottawa. 2004. Archived from the original on 2017-03-25. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "Le territoire". La Nouvelle-France. Resources françaises. Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication (France). 1998. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- Warkentin, Germaine; Podruchny, Carolyn (2001). Decentring the Renaissance: Canada and Europe in Multidisciplinary Perspective, 1500-1700. University of Toronto Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-8020-8149-0.

- "His Most Christian Majesty cedes and guaranties to his said Britannick Majesty, in full right, Canada, with all its dependencies, as well as the island of Cape Breton, and all the other islands and coasts in the gulph and river of St. Lawrence, and in general, every thing that depends on the said countries, lands, islands, and coasts..." – via Wikisource.

- "New France circa 1740". The Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 6 October 2003. Archived from the original on 10 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2009.