Mysticism

Mysticism is the practice of religious ecstasies (religious experiences during alternate states of consciousness), together with whatever ideologies, ethics, rites, myths, legends, and magic may be related to them.[web 1] It may also refer to the attainment of insight in ultimate or hidden truths, and to human transformation supported by various practices and experiences.[web 2]

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

|

Spiritual experience

|

|

Spiritual development |

| Influences |

|

Western General

Antiquity Medieval Early modern Modern |

|

Asian Pre-historic

Iran India East-Asia |

| Research |

|

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Universalism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

Philosophical |

||||

|

Christian

|

||||

|

Other religions

|

||||

|

Spiritual

|

||||

| Category | ||||

The term "mysticism" has Ancient Greek origins with various historically determined meanings.[web 1][web 2] Derived from the Greek word μύω múō, meaning "to close" or "to conceal",[web 2] mysticism referred to the biblical, liturgical, spiritual, and contemplative dimensions of early and medieval Christianity.[1] During the early modern period, the definition of mysticism grew to include a broad range of beliefs and ideologies related to "extraordinary experiences and states of mind."[2]

In modern times, "mysticism" has acquired a limited definition, with broad applications, as meaning the aim at the "union with the Absolute, the Infinite, or God".[web 1] This limited definition has been applied to a wide range of religious traditions and practices,[web 1] valuing "mystical experience" as a key element of mysticism.

Broadly defined, mysticism can be found in all religious traditions, from indigenous religions and folk religions like shamanism, to organised religions like the Abrahamic faiths and Indian religions, and modern spirituality, New Age and New Religious Movements.

Since the 1960s scholars have debated the merits of perennial and constructionist approaches in the scientific research of "mystical experiences".[3][4][5] The perennial position is now "largely dismissed by scholars",[6] most scholars using a contextualist approach, which takes the cultural and historical context into consideration.[7]

Etymology

"Mysticism" is derived from the Greek μυω, meaning "I conceal",[web 2] and its derivative μυστικός, mystikos, meaning 'an initiate'. The verb μυώ has received a quite different meaning in the Greek language, where it is still in use. The primary meanings it has are "induct" and "initiate". Secondary meanings include "introduce", "make someone aware of something", "train", "familiarize", "give first experience of something".[web 3]

The related form of the verb μυέω (mueó or myéō) appears in the New Testament. As explained in Strong's Concordance, it properly means shutting the eyes and mouth to experience mystery. Its figurative meaning is to be initiated into the "mystery revelation". The meaning derives from the initiatory rites of the pagan mysteries.[web 4] Also appearing in the New Testament is the related noun μυστήριον (mustérion or mystḗrion), the root word of the English term "mystery". The term means "anything hidden", a mystery or secret, of which initiation is necessary. In the New Testament it reportedly takes the meaning of the counsels of God, once hidden but now revealed in the Gospel or some fact thereof, the Christian revelation generally, and/or particular truths or details of the Christian revelation.[web 5]

According to Thayer's Greek Lexicon, the term μυστήριον in classical Greek meant "a hidden thing", "secret". A particular meaning it took in Classical antiquity was a religious secret or religious secrets, confided only to the initiated and not to be communicated by them to ordinary mortals. In the Septuagint and the New Testament the meaning it took was that of a hidden purpose or counsel, a secret will. It is sometimes used for the hidden wills of humans, but is more often used for the hidden will of God. Elsewhere in the Bible it takes the meaning of the mystic or hidden sense of things. It is used for the secrets behind sayings, names, or behind images seen in visions and dreams. The Vulgate often translates the Greek term to the Latin sacramentum (sacrament).[web 5]

The related noun μύστης (mustis or mystis, singular) means the initiate, the person initiated to the mysteries.[web 5] According to Ana Jiménez San Cristobal in her study of Greco-Roman mysteries and Orphism, the singular form μύστης and the plural form μύσται are used in ancient Greek texts to mean the person or persons initiated to religious mysteries. These followers of mystery religions belonged to a select group, where access was only gained through an initiation. She finds that the terms were associated with the term βάκχος (Bacchus), which was used for a special class of initiates of the Orphic mysteries. The terms are first found connected in the writings of Heraclitus. Such initiates are identified in texts with the persons who have been purified and have performed certain rites. A passage of the Cretans by Euripides seems to explain that the μύστης (initiate) who devotes himself to an ascetic life, renounces sexual activities, and avoids contact with the dead becomes known as βάκχος. Such initiates were believers in the god Dionysus Bacchus who took on the name of their god and sought an identification with their deity.[8]

Until the sixth century the practice of what is now called mysticism was referred to by the term contemplatio, c.q. theoria.[9] According to Johnson, "[b]oth contemplation and mysticism speak of the eye of love which is looking at, gazing at, aware of divine realities."[9]

Definitions

According to Peter Moore, the term "mysticism" is "problematic but indispensable."[10] It is a generic term which joins together into one concept separate practices and ideas which developed separately,[10] According to Dupré, "mysticism" has been defined in many ways,[11] and Merkur notes that the definition, or meaning, of the term "mysticism" has changed through the ages.[web 1] Moore further notes that the term "mysticism" has become a popular label for "anything nebulous, esoteric, occult, or supernatural."[10]

Parsons warns that "what might at times seem to be a straightforward phenomenon exhibiting an unambiguous commonality has become, at least within the academic study of religion, opaque and controversial on multiple levels".[12] Because of its Christian overtones, and the lack of similar terms in other cultures, some scholars regard the term "mysticism" to be inadequate as a useful descriptive term.[10] Other scholars regard the term to be an inauthentic fabrication,[10][web 1] the "product of post-Enlightenment universalism."[10]

Union with the Divine or Absolute and mystical experience

Deriving from Neo-Platonism and Henosis, mysticism is popularly known as union with God or the Absolute.[13][14] In the 13th century the term unio mystica came to be used to refer to the "spiritual marriage," the ecstasy, or rapture, that was experienced when prayer was used "to contemplate both God’s omnipresence in the world and God in his essence."[web 1] In the 19th century, under the influence of Romanticism, this "union" was interpreted as a "religious experience," which provides certainty about God or a transcendental reality.[web 1][note 1]

An influential proponent of this understanding was William James (1842–1910), who stated that "in mystic states we both become one with the Absolute and we become aware of our oneness."[16] William James popularized this use of the term "religious experience"[note 2] in his The Varieties of Religious Experience,[18][19][web 2] contributing to the interpretation of mysticism as a distinctive experience, comparable to sensory experiences.[20][web 2] Religious experiences belonged to the "personal religion,"[21] which he considered to be "more fundamental than either theology or ecclesiasticism".[21] He gave a Perennialist interpretation to religious experience, stating that this kind of experience is ultimately uniform in various traditions.[note 3]

McGinn notes that the term unio mystica, although it has Christian origins, is primarily a modern expression.[22] McGinn argues that "presence" is more accurate than "union", since not all mystics spoke of union with God, and since many visions and miracles were not necessarily related to union. He also argues that we should speak of "consciousness" of God's presence, rather than of "experience", since mystical activity is not simply about the sensation of God as an external object, but more broadly about "new ways of knowing and loving based on states of awareness in which God becomes present in our inner acts."[23]

However, the idea of "union" does not work in all contexts. For example, in Advaita Vedanta, there is only one reality (Brahman) and therefore nothing other than reality to unite with it—Brahman in each person (atman) has always in fact been identical to Brahman all along. Dan Merkur also notes that union with God or the Absolute is a too limited definition, since there are also traditions which aim not at a sense of unity, but of nothingness, such as Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and Meister Eckhart.[web 1] According to Merkur, Kabbala and Buddhism also emphasize nothingness.[web 1] Blakemore and Jennett note that "definitions of mysticism [...] are often imprecise." They further note that this kind of interpretation and definition is a recent development which has become the standard definition and understanding.[web 6][note 4]

According to Gelman, "A unitive experience involves a phenomenological de-emphasis, blurring, or eradication of multiplicity, where the cognitive significance of the experience is deemed to lie precisely in that phenomenological feature".[web 2][note 5]

Religious ecstasies and interpretative context

Mysticism involves an explanatory context, which provides meaning for mystical and visionary experiences, and related experiences like trances. According to Dan Merkur, mysticism may relate to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness, and the ideas and explanations related to them.[web 1][note 6] Parsons stresses the importance of distinguishing between temporary experiences and mysticism as a process, which is embodied within a "religious matrix" of texts and practices.[26][note 7] Richard Jones does the same.[27] Peter Moore notes that mystical experience may also happen in a spontaneous and natural way, to people who are not committed to any religious tradition. These experiences are not necessarily interpreted in a religious framework.[28] Ann Taves asks by which processes experiences are set apart and deemed religious or mystical.[29]

Intuitive insight and enlightenment

Some authors emphasize that mystical experience involves intuitive understanding of the meaning of existence and of hidden truths, and the resolution of life problems. According to Larson, "mystical experience is an intuitive understanding and realization of the meaning of existence."[30][note 8] According to McClenon, mysticism is "the doctrine that special mental states or events allow an understanding of ultimate truths."[web 7][note 9] According to James R. Horne, mystical illumination is "a central visionary experience [...] that results in the resolution of a personal or religious problem.[3][note 10]

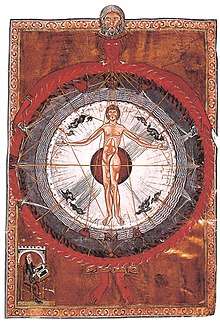

According to Evelyn Underhill, illumination is a generic English term for the phenomenon of mysticism. The term illumination is derived from the Latin illuminatio, applied to Christian prayer in the 15th century.[31] Comparable Asian terms are bodhi, kensho and satori in Buddhism, commonly translated as "enlightenment", and vipassana, which all point to cognitive processes of intuition and comprehension. According to Wright, the use of the western word enlightenment is based on the supposed resemblance of bodhi with Aufklärung, the independent use of reason to gain insight into the true nature of our world, and there are more resemblances with Romanticism than with the Enlightenment: the emphasis on feeling, on intuitive insight, on a true essence beyond the world of appearances.[32]

Spiritual life and re-formation

Other authors point out that mysticism involves more than "mystical experience." According to Gellmann, the ultimate goal of mysticism is human transformation, not just experiencing mystical or visionary states.[web 2][note 12][note 13]</ref>[note 14] According to McGinn, personal transformation is the essential criterion to determine the authenticity of Christian mysticism.[23][note 15]

History of the term

Hellenistic world

In the Hellenistic world, 'mystical' referred to "secret" religious rituals like the Eleusinian Mysteries.[web 2] The use of the word lacked any direct references to the transcendental.[12] A "mystikos" was an initiate of a mystery religion.

Early Christianity

In early Christianity the term "mystikos" referred to three dimensions, which soon became intertwined, namely the biblical, the liturgical and the spiritual or contemplative.[1] The biblical dimension refers to "hidden" or allegorical interpretations of Scriptures.[web 2][1] The liturgical dimension refers to the liturgical mystery of the Eucharist, the presence of Christ in the Eucharist.[web 2][1] The third dimension is the contemplative or experiential knowledge of God.[1]

Until the sixth century, the Greek term theoria, meaning "contemplation" in Latin, was used for the mystical interpretation of the Bible.[9] The link between mysticism and the vision of the Divine was introduced by the early Church Fathers, who used the term as an adjective, as in mystical theology and mystical contemplation.[12] Under the influence of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite the mystical theology came to denote the investigation of the allegorical truth of the Bible,[1] and "the spiritual awareness of the ineffable Absolute beyond the theology of divine names."[36] Pseudo-Dionysius' Apophatic theology, or "negative theology", exerted a great influence on medieval monastic religiosity.[37] It was influenced by Neo-Platonism, and very influential in Eastern Orthodox Christian theology. In western Christianity it was a counter-current to the prevailing Cataphatic theology or "positive theology".

Theoria enabled the Fathers to perceive depths of meaning in the biblical writings that escape a purely scientific or empirical approach to interpretation.[38] The Antiochene Fathers, in particular, saw in every passage of Scripture a double meaning, both literal and spiritual.[39]

Later, theoria or contemplation came to be distinguished from intellectual life, leading to the identification of θεωρία or contemplatio with a form of prayer[40] distinguished from discursive meditation in both East[41] and West.[42]

Medieval meaning

This threefold meaning of "mystical" continued in the Middle Ages.[1] According to Dan Merkur, the term unio mystica came into use in the 13th century as a synonym for the "spiritual marriage," the ecstasy, or rapture, that was experienced when prayer was used "to contemplate both God’s omnipresence in the world and God in his essence."[web 1] Under the influence of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite the mystical theology came to denote the investigation of the allegorical truth of the Bible,[1] and "the spiritual awareness of the ineffable Absolute beyond the theology of divine names."[36] Pseudo-Dionysius' Apophatic theology, or "negative theology", exerted a great influence on medieval monastic religiosity, although it was mostly a male religiosity, since women were not allowed to study.[37] It was influenced by Neo-Platonism, and very influential in Eastern Orthodox Christian theology. In western Christianity it was a counter-current to the prevailing Cataphatic theology or "positive theology". It is best known nowadays in the western world from Meister Eckhart and John of the Cross.

Early modern meaning

In the sixteenth and seventeenth century mysticism came to be used as a substantive.[12] This shift was linked to a new discourse,[12] in which science and religion were separated.[43]

Luther dismissed the allegorical interpretation of the bible, and condemned Mystical theology, which he saw as more Platonic than Christian.[44] "The mystical", as the search for the hidden meaning of texts, became secularised, and also associated with literature, as opposed to science and prose.[45]

Science was also distinguished from religion. By the middle of the 17th century, "the mystical" is increasingly applied exclusively to the religious realm, separating religion and "natural philosophy" as two distinct approaches to the discovery of the hidden meaning of the universe.[46] The traditional hagiographies and writings of the saints became designated as "mystical", shifting from the virtues and miracles to extraordinary experiences and states of mind, thereby creating a newly coined "mystical tradition".[2] A new understanding developed of the Divine as residing within human, an essence beyond the varieties of religious expressions.[12]

Contemporary meaning

The 19th century saw a growing emphasis on individual experience, as a defense against the growing rationalism of western society.[19][web 1] The meaning of mysticism was considerably narrowed:[web 1]

The competition between the perspectives of theology and science resulted in a compromise in which most varieties of what had traditionally been called mysticism were dismissed as merely psychological phenomena and only one variety, which aimed at union with the Absolute, the Infinite, or God—and thereby the perception of its essential unity or oneness—was claimed to be genuinely mystical. The historical evidence, however, does not support such a narrow conception of mysticism.[web 1]

Under the influence of Perennialism, which was popularised in both the west and the east by Unitarianism, Transcendentalists and Theosophy, mysticism has been applied to a broad spectrum of religious traditions, in which all sorts of esotericism and religious traditions and practices are joined together.[47][48][19] The term mysticism was extended to comparable phenomena in non-Christian religions,[web 1] where it influenced Hindu and Buddhist responses to colonialism, resulting in Neo-Vedanta and Buddhist modernism.[48][49]

In the contemporary usage "mysticism" has become an umbrella term for all sorts of non-rational world views,[50] parapsychology and pseudoscience.[51][52][53][54] William Harmless even states that mysticism has become "a catch-all for religious weirdness".[55] Within the academic study of religion the apparent "unambiguous commonality" has become "opaque and controversial".[12] The term "mysticism" is being used in different ways in different traditions.[12] Some call to attention the conflation of mysticism and linked terms, such as spirituality and esotericism, and point at the differences between various traditions.[56]

Variations of mysticism

Based on various definitions of mysticism, namely mysticism as an experience of union or nothingness, mysticism as any kind of an altered state of consciousness which is attributed in a religious way, mysticism as "enlightenment" or insight, and mysticism as a way of transformation, "mysticism" can be found in many cultures and religious traditions, both in folk religion and organized religion. These traditions include practices to induce religious or mystical experiences, but also ethical standards and practices to enhance self-control and integrate the mystical experience into daily life.

Dan Merkur notes, though, that mystical practices are often separated from daily religious practices, and restricted to "religious specialists like monastics, priests, and other renunciates.[web 1]

Western mysticism

Mystery religions

The Eleusinian Mysteries, (Greek: Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια) were annual initiation ceremonies in the cults of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone, held in secret at Eleusis (near Athens) in ancient Greece.[57] The mysteries began in about 1600 B.C. in the Mycenean period and continued for two thousand years, becoming a major festival during the Hellenic era, and later spreading to Rome.[58] Numerous scholars have proposed that the power of the Eleusinian Mysteries came from the kykeon's functioning as an entheogen.[59]

Christian mysticism

Early Christianity

The apophatic theology, or "negative theology", of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (6th c.) exerted a great influence on medieval monastic religiosity, both in the East and (by Latin translation) in the West.[37] Pseudo-Dionysius applied Neoplatonic thought, particularly that of Proclus, to Christian theology.

Orthodox Christianity

The Orthodox Church has a long tradition of theoria (intimate experience) and hesychia (inner stillness), in which contemplative prayer silences the mind to progress along the path of theosis (deification).

Theosis, practical unity with and conformity to God, is obtained by engaging in contemplative prayer, the first stage of theoria,[60][note 16] which results from the cultivation of watchfulness (nepsis). In theoria, one comes to behold the "divisibly indivisible" divine operations (energeia) of God as the "uncreated light" of transfiguration, a grace which is eternal and proceeds naturally from the blinding darkness of the incomprehensible divine essence.[note 17][note 18] It is the main aim of hesychasm, which was developed in the thought St. Symeon the New Theologian, embraced by the monastic communities on Mount Athos, and most notably defended by St. Gregory Palamas against the Greek humanist philosopher Barlaam of Calabria. According to Roman Catholic critics, hesychastic practice has its roots to the introduction of a systematic practical approach to quietism by Symeon the New Theologian.[note 19]

Symeon believed that direct experience gave monks the authority to preach and give absolution of sins, without the need for formal ordination. While Church authorities also taught from a speculative and philosophical perspective, Symeon taught from his own direct mystical experience,[63] and met with strong resistance for his charismatic approach, and his support of individual direct experience of God's grace.[63]

Western Europe

The High Middle Ages saw a flourishing of mystical practice and theorization in western Roman Catholicism, corresponding to the flourishing of new monastic orders, with such figures as Guigo II, Hildegard of Bingen, Bernard of Clairvaux, the Victorines, all coming from different orders, as well as the first real flowering of popular piety among the laypeople.

The Late Middle Ages saw the clash between the Dominican and Franciscan schools of thought, which was also a conflict between two different mystical theologies: on the one hand that of Dominic de Guzmán and on the other that of Francis of Assisi, Anthony of Padua, Bonaventure, and Angela of Foligno. This period also saw such individuals as John of Ruysbroeck, Catherine of Siena and Catherine of Genoa, the Devotio Moderna, and such books as the Theologia Germanica, The Cloud of Unknowing and The Imitation of Christ.

Moreover, there was the growth of groups of mystics centered around geographic regions: the Beguines, such as Mechthild of Magdeburg and Hadewijch (among others); the Rhineland mystics Meister Eckhart, Johannes Tauler and Henry Suso; and the English mystics Richard Rolle, Walter Hilton and Julian of Norwich. The Spanish mystics included Teresa of Avila, John of the Cross and Ignatius Loyola.

The later post-reformation period also saw the writings of lay visionaries such as Emanuel Swedenborg and William Blake, and the foundation of mystical movements such as the Quakers. Catholic mysticism continued into the modern period with such figures as Padre Pio and Thomas Merton.

The philokalia, an ancient method of Eastern Orthodox mysticism, was promoted by the twentieth century Traditionalist School. The allegedly inspired or "channeled" work A Course in Miracles represents a blending of non-denominational Christian and New Age ideas.

Western esotericism and modern spirituality

Many western esoteric traditions and elements of modern spirituality have been regarded as "mysticism," such as Gnosticism, Transcendentalism, Theosophy, the Fourth Way,[64] and Neo-Paganism. Modern western spiritually and transpersonal psychology combine western psycho-therapeutic practices with religious practices like meditation to attain a lasting transformation. Nature mysticism is an intense experience of unification with nature or the cosmic totality, which was popular with Romantic writers.[65]

Jewish mysticism

| Jewish mysticism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Forms

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

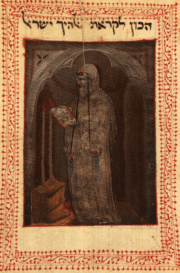

In the common era, Judaism has had two main kinds of mysticism: Merkabah mysticism and Kabbalah. The former predated the latter, and was focused on visions, particularly those mentioned in the Book of Ezekiel. It gets its name from the Hebrew word meaning "chariot", a reference to Ezekiel's vision of a fiery chariot composed of heavenly beings.

Kabbalah is a set of esoteric teachings meant to explain the relationship between an unchanging, eternal and mysterious Ein Sof (no end) and the mortal and finite universe (his creation). Inside Judaism, it forms the foundations of mystical religious interpretation.

Kabbalah originally developed entirely within the realm of Jewish thought. Kabbalists often use classical Jewish sources to explain and demonstrate its esoteric teachings. These teachings are thus held by followers in Judaism to define the inner meaning of both the Hebrew Bible and traditional Rabbinic literature, their formerly concealed transmitted dimension, as well as to explain the significance of Jewish religious observances.[66]

Kabbalah emerged, after earlier forms of Jewish mysticism, in 12th to 13th century Southern France and Spain, becoming reinterpreted in the Jewish mystical renaissance of 16th-century Ottoman Palestine. It was popularised in the form of Hasidic Judaism from the 18th century forward. 20th-century interest in Kabbalah has inspired cross-denominational Jewish renewal and contributed to wider non-Jewish contemporary spirituality, as well as engaging its flourishing emergence and historical re-emphasis through newly established academic investigation.

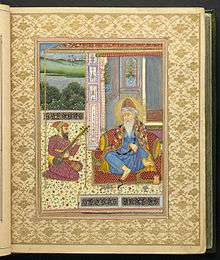

Islamic mysticism

Sufism is said to be Islam's inner and mystical dimension.[67][68][69] Classical Sufi scholars have defined Sufism as

[A] science whose objective is the reparation of the heart and turning it away from all else but God.[70]

A practitioner of this tradition is nowadays known as a ṣūfī (صُوفِيّ), or, in earlier usage, a dervish. The origin of the word "Sufi" is ambiguous. One understanding is that Sufi means wool-wearer; wool wearers during early Islam were pious ascetics who withdrew from urban life. Another explanation of the word "Sufi" is that it means 'purity'.[71]

Sufis generally belong to a khalqa, a circle or group, led by a Sheikh or Murshid. Sufi circles usually belong to a Tariqa which is the Sufi order and each has a Silsila, which is the spiritual lineage, which traces its succession back to notable Sufis of the past, and often ultimately to the last prophet Muhammed or one of his close associates. The turuq (plural of tariqa) are not enclosed like Christian monastic orders; rather the members retain an outside life. Membership of a Sufi group often passes down family lines. Meetings may or may not be segregated according to the prevailing custom of the wider society. An existing Muslim faith is not always a requirement for entry, particularly in Western countries.

Sufi practice includes

- Dhikr, or remembrance (of God), which often takes the form of rhythmic chanting and breathing exercises.

- Sama, which takes the form of music and dance — the whirling dance of the Mevlevi dervishes is a form well known in the West.

- Muraqaba or meditation.

- Visiting holy places, particularly the tombs of Sufi saints, in order to remember death and the greatness of those who have passed.

The aims of Sufism include: the experience of ecstatic states (hal), purification of the heart (qalb), overcoming the lower self (nafs), extinction of the individual personality (fana), communion with God (haqiqa), and higher knowledge (marifat). Some sufic beliefs and practices have been found unorthodox by other Muslims; for instance Mansur al-Hallaj was put to death for blasphemy after uttering the phrase Ana'l Haqq, "I am the Truth" (i.e. God) in a trance.

Notable classical Sufis include Jalaluddin Rumi, Fariduddin Attar, Sultan Bahoo, Sayyed Sadique Ali Husaini, Saadi Shirazi and Hafez, all major poets in the Persian language. Omar Khayyam, Al-Ghazzali and Ibn Arabi were renowned scholars. Abdul Qadir Jilani, Moinuddin Chishti, and Bahauddin Naqshband founded major orders, as did Rumi. Rabia Basri was the most prominent female Sufi.

Sufism first came into contact with the Judeo-Christian world during the Moorish occupation of Spain. An interest in Sufism revived in non-Muslim countries during the modern era, led by such figures as Inayat Khan and Idries Shah (both in the UK), Rene Guenon (France) and Ivan Aguéli (Sweden). Sufism has also long been present in Asian countries that do not have a Muslim majority, such as India and China.[72]

Indian religions

Hinduism

In Hinduism, various sadhanas aim at overcoming ignorance (avidhya) and transcending the limited identification with body, mind and ego to attain moksha. Hinduism has a number of interlinked ascetic traditions and philosophical schools which aim at moksha[73] and the acquisition of higher powers.[74] With the onset of the British colonisation of India, those traditions came to be interpreted in western terms such as "mysticism", drawing equivalents with western terms and practices.[75]

Yoga is the physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which aim to attain a state of permanent peace.[76] Various traditions of yoga are found in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.[77][78][79][78] The Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali defines yoga as "the stilling of the changing states of the mind,"[80] which is attained in samadhi.

Classical Vedanta gives philosophical interpretations and commentaries of the Upanishads, a vast collection of ancient hymns. At least ten schools of Vedanta are known,[81] of which Advaita Vedanta, Vishishtadvaita, and Dvaita are the best known.[82] Advaita Vedanta, as expounded by Adi Shankara, states that there is no difference between Atman and Brahman. The best-known subschool is Kevala Vedanta or mayavada as expounded by Adi Shankara. Advaita Vedanta has acquired a broad acceptance in Indian culture and beyond as the paradigmatic example of Hindu spirituality.[83] In contrast Bhedabheda-Vedanta emphasizes that Atman and Brahman are both the same and not the same,[84] while Dvaita Vedanta states that Atman and God are fundamentally different.[84] In modern times, the Upanishads have been interpreted by Neo-Vedanta as being "mystical".[75]

Various Shaivist traditions are strongly nondualistic, such as Kashmir Shaivism and Shaiva Siddhanta.

Tantra

Tantra is the name given by scholars to a style of meditation and ritual which arose in India no later than the fifth century AD.[85] Tantra has influenced the Hindu, Bön, Buddhist, and Jain traditions and spread with Buddhism to East and Southeast Asia.[86] Tantric ritual seeks to access the supra-mundane through the mundane, identifying the microcosm with the macrocosm.[87] The Tantric aim is to sublimate (rather than negate) reality.[88] The Tantric practitioner seeks to use prana (energy flowing through the universe, including one's body) to attain goals which may be spiritual, material or both.[89] Tantric practice includes visualisation of deities, mantras and mandalas. It can also include sexual and other (antinomian) practices.

Sant-tradition and Sikhism

Mysticism in the Sikh dharm began with its founder, Guru Nanak, who as a child had profound mystical experiences.[90] Guru Nanak stressed that God must be seen with 'the inward eye', or the 'heart', of a human being.[91] Guru Arjan, the fifth Sikh Guru, added religious mystics belonging to other religions into the holy scriptures that would eventually become the Guru Granth Sahib.

The goal of Sikhism is to be one with God.[92] Sikhs meditate as a means to progress towards enlightenment; it is devoted meditation simran that enables a sort of communication between the Infinite and finite human consciousness.[93] There is no concentration on the breath but chiefly the remembrance of God through the recitation of the name of God[94] and surrender themselves to God's presence often metaphorized as surrendering themselves to the Lord's feet.[95]

Buddhism

According to Oliver, Buddhism is mystical in the sense that it aims at the identification of the true nature of our self, and live according to it.[96] Buddhism originated in India, sometime between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, but is now mostly practiced in other countries, where it developed into a number of traditions, the main ones being Therevada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana.

Buddhism aims at liberation from the cycle of rebirth by self-control through meditation and morally just behaviour. Some Buddhist paths aim at a gradual development and transformation of the personality toward Nirvana, like the Theravada stages of enlightenment. Others, like the Japanese Rinzai Zen tradition, emphasize sudden insight, but nevertheless also prescribe intensive training, including meditation and self-restraint.

Although Theravada does not acknowledge the existence of a theistic Absolute, it does postulate Nirvana as a transcendent reality which may be attained.[97][98] It further stresses transformation of the personality through meditative practice, self-restraint, and morally just behaviour.[97] According to Richard H. Jones, Theravada is a form of mindful extrovertive and introvertive mysticism, in which the conceptual structuring of experiences is weakened, and the ordinary sense of self is weakened.[99] It is best known in the west from the Vipassana movement, a number of branches of modern Theravāda Buddhism from Burma, Laos, Thailand and Sri Lanka, and includes contemporary American Buddhist teachers such as Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield.

The Yogacara school of Mahayana investigates the workings of the mind, stating that only the mind[100] (citta-mātra) or the representations we cognize (vijñapti-mātra),[101][note 20] really exist.[100][102][101] In later Buddhist Mahayana thought, which took an idealistic turn,[note 21] the unmodified mind came to be seen as a pure consciousness, from which everything arises.[note 22] Vijñapti-mātra, coupled with Buddha-nature or tathagatagarba, has been an influential concept in the subsequent development of Mahayana Buddhism, not only in India, but also in China and Tibet, most notable in the Chán (Zen) and Dzogchen traditions.

Chinese and Japanese Zen is grounded on the Chinese understanding of the Buddha-nature as one true's essence, and the Two truths doctrine as a polarity between relative and Absolute reality.[105][106] Zen aims at insight one's true nature, or Buddha-nature, thereby manifesting Absolute reality in the relative reality.[107] In Soto, this Buddha-nature is regarded to be ever-present, and shikan-taza, sitting meditation, is the expression of the already existing Buddhahood.[106] Rinzai-zen emphasises the need for a break-through insight in this Buddha-nature,[106] but also stresses that further practice is needed to deepen the insight and to express it in daily life,[108][109][110][111] as expressed in the Three mysterious Gates, the Four Ways of Knowing of Hakuin,[112] and the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures.[113] The Japanese Zen-scholar D.T. Suzuki noted similarities between Zen-Buddhism and Christian mysticism, especially meister Eckhart.[114]

The Tibetan Vajrayana tradition is based on Madhyamaka philosophy and Tantra.[115] In deity yoga, visualizations of deities are eventually dissolved, to realize the inherent emptiness of every-'thing' that exists.[116] Dzogchen, which is being taught in both the Tibetan buddhist Nyingma school and the Bön tradition,[117][118] focuses on direct insight into our real nature. It holds that "mind-nature" is manifested when one is enlightened,[119] being nonconceptually aware (rigpa, "open presence") of one's nature,[117] "a recognition of one's beginningless nature."[120] Mahamudra has similarities with Dzogchen, emphasizing the meditational approach to insight and liberation.

Taoism

Taoist philosophy is centered on the Tao, usually translated "Way", an ineffable cosmic principle. The contrasting yet interdependent concepts of yin and yang also symbolise harmony, with Taoist scriptures often emphasing the Yin virtues of femininity, passivity and yieldingness.[121] Taoist practice includes exercises and rituals aimed at manipulating the life force Qi, and obtaining health and longevity.[note 23] These have been elaborated into practices such as Tai chi, which are well known in the west.

The Secularization of Mysticism

Today there is also occurring in the West what Richard Jones calls "the secularization of mysticism".[122] That is the separation of meditation and other mystical practices from their traditional use in religious ways of life to only secular ends of purported psychological and physiological benefits.

Scholarly approaches of mysticism and mystical experience

Types of mysticism

R. C. Zaehner distinguishes three fundamental types of mysticism, namely theistic, monistic and panenhenic ("all-in-one") or natural mysticism.[4] The theistic category includes most forms of Jewish, Christian and Islamic mysticism and occasional Hindu examples such as Ramanuja and the Bhagavad Gita.[4] The monistic type, which according to Zaehner is based upon an experience of the unity of one's soul,[4][note 24] includes Buddhism and Hindu schools such as Samkhya and Advaita vedanta.[4] Nature mysticism seems to refer to examples that do not fit into one of these two categories.[4]

Walter Terence Stace, in his book Mysticism and Philosophy (1960), distinguished two types of mystical experience, namely extrovertive and introvertive mysticism.[123][4][124] Extrovertive mysticism is an experience of the unity of the external world, whereas introvertive mysticism is "an experience of unity devoid of perceptual objects; it is literally an experience of 'no-thing-ness'."[124] The unity in extrovertive mysticism is with the totality of objects of perception. While perception stays continuous, “unity shines through the same world”; the unity in introvertive mysticism is with a pure consciousness, devoid of objects of perception,[125] “pure unitary consciousness, wherein awareness of the world and of multiplicity is completely obliterated.”[126] According to Stace such experiences are nonsensous and nonintellectual, under a total “suppression of the whole empirical content.”[127]

Stace argues that doctrinal differences between religious traditions are inappropriate criteria when making cross-cultural comparisons of mystical experiences.[4] Stace argues that mysticism is part of the process of perception, not interpretation, that is to say that the unity of mystical experiences is perceived, and only afterwards interpreted according to the perceiver's background. This may result in different accounts of the same phenomenon. While an atheist describes the unity as “freed from empirical filling”, a religious person might describe it as “God” or “the Divine”.[128]

Mystical experiences

Since the 19th century, mystical experience has evolved as a distinctive concept. It is closely related to "mysticism" but lays sole emphasis on the experiential aspect, be it spontaneous or induced by human behavior, whereas mysticism encompasses a broad range of practices aiming at a transformation of the person, not just inducing mystical experiences.

William James' The Varieties of Religious Experience is the classic study on religious or mystical experience, which influenced deeply both the academic and popular understanding of "religious experience".[18][19][20][web 2] He popularized the use of the term "religious experience"[note 25] in his "Varieties",[18][19][web 2] and influenced the understanding of mysticism as a distinctive experience which supplies knowledge of the transcendental:[20][web 2]

Under the influence of William James' The Varieties of Religious Experience, heavily centered on people's conversion experiences, most philosophers' interest in mysticism has been in distinctive, allegedly knowledge-granting "mystical experiences.""[web 2]

Yet, Gelman notes that so-called mystical experience is not a transitional event, as William James claimed, but an "abiding consciousness, accompanying a person throughout the day, or parts of it. For that reason, it might be better to speak of mystical consciousness, which can be either fleeting or abiding."[web 2]

Most mystical traditions warn against an attachment to mystical experiences, and offer a "protective and hermeneutic framework" to accommodate these experiences.[129] These same traditions offer the means to induce mystical experiences,[129] which may have several origins:

- Spontaneous; either apparently without any cause, or by persistent existential concerns, or by neurophysiological origins;

- Religious practices, such as contemplation, meditation, and mantra-repetition;

- Entheogens (psychedelic drugs)

- Neurophysiological origins, such as temporal lobe epilepsy.

The theoretical study of mystical experience has shifted from an experiential, privatized and perennialist approach to a contextual and empirical approach.[129] The experientalist approach sees mystical experience as a private expression of perennial truths, separate from its historical and cultural context. The contextual approach, which also includes constructionism and attribution theory, takes into account the historical and cultural context.[129][29][web 2] Neurological research takes an empirical approach, relating mystical experiences to neurological processes.

Perennialism versus constructionism

The term "mystical experience" evolved as a distinctive concept since the 19th century, laying sole emphasis on the experiential aspect, be it spontaneous or induced by human behavior. Perennialists regard those various experience traditions as pointing to one universal transcendental reality, for which those experiences offer the proof. In this approach, mystical experiences are privatised, separated from the context in which they emerge.[129] Well-known representatives are William James, R.C. Zaehner, William Stace and Robert Forman.[7] The perennial position is "largely dismissed by scholars",[6] but "has lost none of its popularity."[130]

In contrast, for the past decades most scholars have favored a constructionist approach, which states that mystical experiences are fully constructed by the ideas, symbols and practices that mystics are familiar with.[7] Critics of the term "religious experience" note that the notion of "religious experience" or "mystical experience" as marking insight into religious truth is a modern development,[131] and contemporary researchers of mysticism note that mystical experiences are shaped by the concepts "which the mystic brings to, and which shape, his experience".[132] What is being experienced is being determined by the expectations and the conceptual background of the mystic.[133]

Richard Jones draws a distinction between "anticonstructivism" and "perennialism": constructivism can be rejected with respect to a certain class of mystical experiences without ascribing to a perennialist philosophy on the relation of mystical doctrines.[134] One can reject constructivism without claiming that mystical experiences reveal a cross-cultural "perennial truth". For example, a Christian can reject both constructivism and perennialism in arguing that there is a union with God free of cultural construction. Constructivism versus anticonstructivism is a matter of the nature of mystical experiences while perennialism is a matter of mystical traditions and the doctrines they espouse.

Contextualism and attribution theory

The perennial position is now "largely dismissed by scholars",[6] and the contextual approach has become the common approach.[129] Contextualism takes into account the historical and cultural context of mystical experiences.[129] The attribution approach views "mystical experience" as non-ordinary states of consciousness which are explained in a religious framework.[29] According to Proudfoot, mystics unconsciously merely attribute a doctrinal content to ordinary experiences. That is, mystics project cognitive content onto otherwise ordinary experiences having a strong emotional impact.[135][29] This approach has been further elaborated by Ann Taves, in her Religious Experience Reconsidered. She incorporates both neurological and cultural approaches in the study of mystical experience.

Neurological research

Neurological research takes an empirical approach, relating mystical experiences to neurological processes.[136][137] This leads to a central philosophical issue: does the identification of neural triggers or neural correlates of mystical experiences prove that mystical experiences are no more than brain events or does it merely identify the brain activity occurring during a genuine cognitive event? The most common positions are that neurology reduces mystical experiences or that neurology is neutral to the issue of mystical cognitivity.[138]

Interest in mystical experiences and psychedelic drugs has also recently seen a resurgence.[139]

The temporal lobe seems to be involved in mystical experiences,[web 9][140] and in the change in personality that may result from such experiences.[web 9] It generates the feeling of "I," and gives a feeling of familiarity or strangeness to the perceptions of the senses.[web 9] There is a long-standing notion that epilepsy and religion are linked,[141] and some religious figures may have had temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE).[web 9][142][143][141]

The anterior insula may be involved in ineffability, a strong feeling of certainty which cannot be expressed in words, which is a common quality in mystical experiences. According to Picard, this feeling of certainty may be caused by a dysfunction of the anterior insula, a part of the brain which is involved in interoception, self-reflection, and in avoiding uncertainty about the internal representations of the world by "anticipation of resolution of uncertainty or risk".[144][note 26]

Mysticism and morality

A philosophical issue in the study of mysticism is the relation of mysticism to morality. Albert Schweitzer presented the classic account of mysticism and morality being incompatible.[145] Arthur Danto also argued that morality is at least incompatible with Indian mystical beliefs.[146] Walter Stace, on the other hand, argued not only are mysticism and morality compatible, but that mysticism is the source and justification of morality.[147] Others studying multiple mystical traditions have concluded that the relation of mysticism and morality is not as simple as that.[148][149]

Richard King also points to disjunction between "mystical experience" and social justice:[150]

The privatisation of mysticism – that is, the increasing tendency to locate the mystical in the psychological realm of personal experiences – serves to exclude it from political issues as social justice. Mysticism thus becomes seen as a personal matter of cultivating inner states of tranquility and equanimity, which, rather than seeking to transform the world, serve to accommodate the individual to the status quo through the alleviation of anxiety and stress.[150]

See also

Notes

- Note that Parmenides' "way of truth" may also be translated as "way of conviction." Parmenides (fl. late sixth or early fifth century BC), in his poem On Nature, gives an account of a revelation on two ways of inquiry. "The way of conviction" explores Being, true reality ("what-is"), which is "What is ungenerated and deathless,/whole and uniform, and still and perfect."[15] "The way of opinion" is the world of appearances, in which one's sensory faculties lead to conceptions which are false and deceitful. Cook's translation "way of conviction" is rendered by other translators as "way of truth."

- The term "mystical experience" has become synonymous with the terms "religious experience", spiritual experience and sacred experience.[17]

- William James: "This is the everlasting and triumphant mystical tradition, hardly altered by differences of clime or creed. In Hinduism, in Neoplatonism, in Sufism, in Christian mysticism, in Whitmanism, we find the same recurring note, so that there is about mystical utterances an eternal unanimity which ought to make a critic stop and think, and which bring it about that the mystical classics have, as been said, neither birthday nor native land."[16]

- Blakemore and Jennett: "Mysticism is frequently defined as an experience of direct communion with God, or union with the Absolute, but definitions of mysticism (a relatively modern term) are often imprecise and usually rely on the presuppositions of the modern study of mysticism — namely, that mystical experiences involve a set of intense and usually individual and private psychological states [...] Furthermore, mysticism is a phenomenon said to be found in all major religious traditions.[web 6] Blakemore and Jennett add: "[T]he common assumption that all mystical experiences, whatever their context, are the same cannot, of course, be demonstrated." They also state: "Some have placed a particular emphasis on certain altered states, such as visions, trances, levitations, locutions, raptures, and ecstasies, many of which are altered bodily states. Margery Kempe's tears and Teresa of Avila's ecstasies are famous examples of such mystical phenomena. But many mystics have insisted that while these experiences may be a part of the mystical state, they are not the essence of mystical experience, and some, such as Origen, Meister Eckhart, and John of the Cross, have been hostile to such psycho-physical phenomena. Rather, the essence of the mystical experience is the encounter between God and the human being, the Creator and creature; this is a union which leads the human being to an ‘absorption’ or loss of individual personality. It is a movement of the heart, as the individual seeks to surrender itself to ultimate Reality; it is thus about being rather than knowing. For some mystics, such as Teresa of Avila, phenomena such as visions, locutions, raptures, and so forth are by-products of, or accessories to, the full mystical experience, which the soul may not yet be strong enough to receive. Hence these altered states are seen to occur in those at an early stage in their spiritual lives, although ultimately only those who are called to achieve full union with God will do so."[web 6]

- Gelman: "Examples are experiences of the oneness of all of nature, “union” with God, as in Christian mysticism, (see section 2.2.1), the Hindu experience that Atman is Brahman (that the self/soul is identical with the eternal, absolute being), the Buddhist unconstructed experience, and “monistic” experiences, devoid of all multiplicity."[web 2]

Compare Plotinus, who argued that The One is radically simple, and does not even have self-knowledge, since self-knowledge would imply multiplicity.[24] Nevertheless, Plotinus does urge for a search for the Absolute, turning inward and becoming aware of the "presence of the intellect in the human soul," initiating an ascent of the soul by abstraction or "taking away," culminating in a sudden appearance of the One.[25] - Merkur: "Mysticism is the practice of religious ecstasies (religious experiences during alternate states of consciousness), together with whatever ideologies, ethics, rites, myths, legends, and magic may be related to them."[web 1]

- Parsons: "...episodic experience and mysticism as a process that, though surely punctuated by moments of visionary, unitive, and transformative encounters, is ultimately inseparable from its embodied relation to a total religious matrix: liturgy, scripture, worship, virtues, theology, rituals, practice and the arts.[26]

- Larson: "A mystical experience is an intuitive understanding and realization of the meaning of existence – an intuitive understanding and realization which is intense, integrating, self-authenticating, liberating – i.e., providing a sense of release from ordinary self-awareness – and subsequently determinative – i.e., a primary criterion – for interpreting all other experience whether cognitive, conative, or affective."[30]

- McClenon: "The doctrine that special mental states or events allow an understanding of ultimate truths. Although it is difficult to differentiate which forms of experience allow such understandings, mental episodes supporting belief in "other kinds of reality" are often labeled mystical [...] Mysticism tends to refer to experiences supporting belief in a cosmic unity rather than the advocation of a particular religious ideology."[web 7]

- Horne: "[M]ystical illumination is interpreted as a central visionary experience in a psychological and behavioural process that results in the resolution of a personal or religious problem. This factual, minimal interpretation depicts mysticism as an extreme and intense form of the insight seeking process that goes in activities such as solving theoretical problems or developing new inventions.[3]

- Original quote in "Evelyn Underhill (1930), Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness.<ref name='FOOTNOTEUnderhill2012xiv'>Underhill 2012, p. xiv.

- Gellman: "Typically, mystics, theistic or not, see their mystical experience as part of a larger undertaking aimed at human transformation (See, for example, Teresa of Avila, Life, Chapter 19) and not as the terminus of their efforts. Thus, in general, ‘mysticism’ would best be thought of as a constellation of distinctive practices, discourses, texts, institutions, traditions, and experiences aimed at human transformation, variously defined in different traditions."[web 2] According to Evelyn Underhill, mysticism is "the science or art of the spiritual life."[33][note 11]

- Underhill: "One of the most abused words in the English language, it has been used in different and often mutually exclusive senses by religion, poetry, and philosophy: has been claimed as an excuse for every kind of occultism, for dilute transcendentalism, vapid symbolism, religious or aesthetic sentimentality, and bad metaphysics. on the other hand, it has been freely employed as a term of contempt by those who have criticized these things. It is much to be hoped that it may be restored sooner or later to its old meaning, as the science or art of the spiritual life."[33]

- According to Waaijman, the traditional meaning of spirituality is a process of re-formation which "aims to recover the original shape of man, the image of God. To accomplish this, the re-formation is oriented at a mold, which represents the original shape: in Judaism the Torah, in Christianity Christ, in Buddhism Buddha, in the Islam Muhammad."[34] Waaijman uses the word "omvorming",[34] "to change the form". Different translations are possible: transformation, re-formation, trans-mutation. Waaijman points out that "spirituality" is only one term of a range of words which denote the praxis of spirituality.[35] Some other terms are "Hasidism, contemplation, kabbala, asceticism, mysticism, perfection, devotion and piety".[35]

- McGinn: "This is why the only test that Christianity has known for determining the authenticity of a mystic and her or his message has been that of personal transformation, both on the mystic's part and—especially—on the part of those whom the mystic has affected.[23]

- Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos: "Noetic prayer is the first stage of theoria."[60]

- Theophan the Recluse: "The contemplative mind sees God, in so far as this is possible for man."[61]

- Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos: "This is what Saint Symeon the New Theologian teaches. In his poems, proclaims over and over that, while beholding the uncreated Light, the deified man acquires the Revelation of God the Trinity. Being in "theoria" (vision of God), the saints do not confuse the hypostatic attributes. The fact that the Latin tradition came to the point of confusing these hypostatic attributes and teaching that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Son also, shows the non-existence of empirical theology for them. Latin tradition speaks also of created grace, a fact which suggests that there is no experience of the grace of God. For, when man obtains the experience of God, then he comes to understand well that this grace is uncreated. Without this experience there can be no genuine "therapeutic tradition.""[60]

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "But it was Simeon, "the new theologian" (c. 1025-c. 1092; see Krumbacher, op. cit., 152–154), a monk of Studion, the "greatest mystic of the Greek Church" (loc. cit.), who evolved the quietist theory so elaborately that he may be called the father of Hesychasm. For the union with God in contemplation (which is the highest object of our life) he required a regular system of spiritual education beginning with baptism and passing through regulated exercises of penance and asceticism under the guidance of a director. But he had not conceived the grossly magic practices of the later Hesychasts; his ideal is still enormously more philosophical than theirs."[62]

- "Representation-only"[101] or "mere representation."[web 8]

- Oxford reference: "Some later forms of Yogācāra lend themselves to an idealistic interpretation of this theory but such a view is absent from the works of the early Yogācārins such as Asaṇga and Vasubandhu."[web 8]

- Yogacara postulates an advaya (nonduality) of grahaka ("grasping," cognition)[102] and gradya (the "grasped," cognitum).[102] In Yogacara-thought, cognition is a modification of the base-consciousness, alaya-vijnana.[103] According to the Lankavatara Sutra and the schools of Chan/Zen Buddhism, this unmodified mind is identical with the tathagata-garbha, the "womb of Buddhahood," or Buddha-nature, the nucleus of Buddhahood inherent in everyone. Both denoye the potentiality of attaining Buddhahood.[104] In the Lankavatara-interpretation, tathagata-garbha as a potentiality turned into a metaphysical Absolute reality which had to be realised.

- Extending to physical immortality: the Taoist pantheon includes Xian, or immortals.

- Compare the work of C.G. Jung.

- The term "mystical experience" has become synonymous with the terms "religious experience", spiritual experience and sacred experience.[17]

- See also Francesca Sacco (2013-09-19), Can Epilepsy Unlock The Secret To Happiness?, Le Temps

References

- King 2002, p. 15.

- King 2002, pp. 17–18.

- Horne 1996, p. 9.

- Paden 2009, p. 332.

- Forman 1997, p. 197, note 3.

- McMahan 2008, p. 269, note 9.

- Moore 2005, p. 6356–6357.

- San Cristobal (2009), p. 51-52

- Johnson 1997, p. 24.

- Moore 2005, p. 6355.

- Dupré 2005.

- Parsons 2011, p. 3.

- McGinn 2005.

- Moore 2005.

- Cook 2013, p. 109-111.

- Harmless 2007, p. 14.

- Samy 1998, p. 80.

- Hori 1999, p. 47.

- Sharf 2000.

- Harmless 2007, pp. 10–17.

- James 1982, p. 30.

- McGinn 2005, p. 6334.

- McGinn 2006.

- Mooney 2009, p. 7.

- Mooney 2009, p. 8.

- Parsons 2011, pp. 4–5.

- Jones 2016, chapter 1.

- Moore 2005, p. 6356.

- Taves 2009.

- Lidke 2005, p. 144.

- Underhill 2008.

- Wright 2000, pp. 181–183.

- Underhill 2012, p. xiv.

- Waaijman 2000, p. 460.

- Waaijman 2002, p. 315.

- Dupré 2005, p. 6341.

- King 2002, p. 195.

- John Breck, Scripture in Tradition: The Bible and Its Interpretation in the Orthodox Church, St Vladimir's Seminary Press 2001, p. 11.

- Breck, Scripture in Tradition, p. 37.

- Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article contemplation, contemplative life

- Mattá al-Miskīn, Orthodox Prayer Life: The Interior Way (St Vladimir's Seminary Press 2003 ISBN 0-88141-250-3), pp. 55–56

- "Augustin Poulain, "Contemplation", in The Catholic Encyclopedia 1908". Archived from the original on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- King 2002, pp. 16–18.

- King 2002, p. 16.

- King 2002, pp. 16–17.

- King 2002, p. 17.

- Hanegraaff 1996.

- King 2002.

- McMahan 2010.

- Parsons 2011, p. 3-5.

- Ben-Shakhar, Gershon; Bar, Marianna (2018-06-08). The Lying Machine: Mysticism and Pseudo-Science in Personality Assessment and Prediction. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781138301030.

- Shermer, Michael; Linse, Pat (2002). The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576076538.

- Smith, Jonathan C. (2011-09-26). Pseudoscience and Extraordinary Claims of the Paranormal: A Critical Thinker's Toolkit. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444358940.

- Eburne, Jonathan (2018-09-18). Outsider Theory: Intellectual Histories of Questionable Ideas. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9781452958255.

- Harmless 2007, p. 3.

- Parsons 2011, pp. 3–4.

- Kerényi, Karoly, "Kore," in C.G. Jung and C. Kerényi, Essays on a Science of Mythology: The Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963: pages 101–55.

- Eliade, Mircea, A History of Religious Ideas: From the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

- Webster, P. (April 1999). "The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries. Twentieth Anniversary Edition, by R. Gordon Wasson, Albert Hofmann, Carl A.P. Ruck, Hermes Press, 1998. (Originally published by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich in 1978). ISBN 0-915148-20-X". International Journal of Drug Policy. 10 (2): 157–166. doi:10.1016/s0955-3959(99)00012-2. ISSN 0955-3959.

- Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos, The Difference Between Orthodox Spirituality and Other Traditions

- Theophan the Recluse, What Is prayer?. Cited in The Art of Prayer: An Orthodox Anthology, p.73, compiled by Igumen Chariton of Valamo, trans, E. Kadloubovsky and E.M. Palmer, ed. Timothy Ware, 1966, Faber & Faber, London.

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Hesychasm". www.newadvent.org.

- deCatanzaro 1980, pp. 9–10.

- Magee 2016.

- Dupré 2005, p. 6342.

- "Imbued with Holiness" – The relationship of the esoteric to the exoteric in the fourfold Pardes interpretation of Torah and existence. From www.kabbalaonline.org

- Alan Godlas, University of Georgia, Sufism's Many Paths, 2000, University of Georgia Archived 2011-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Nuh Ha Mim Keller, "How would you respond to the claim that Sufism is Bid'a?", 1995. Fatwa accessible at: Masud.co.uk

- Zubair Fattani, "The meaning of Tasawwuf", Islamic Academy. Islamicacademy.org

- Ahmed Zarruq, Zaineb Istrabadi, Hamza Yusuf Hanson—"The Principles of Sufism". Amal Press. 2008.

- Seyyedeh Dr. Nahid Angha. "origin of the Wrod Tasawouf". Ias.org. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- Johnson, Ian (25 April 2013). "China's Sufis: The Shrines Behind the Dunes".

- Raju 1992.

- White 2012.

- King 2001.

- Bryant 2009, p. 10, 457.

- Denise Lardner Carmody, John Carmody, Serene Compassion. Oxford University Press US, 1996, page 68.

- Stuart Ray Sarbacker, Samādhi: The Numinous and Cessative in Indo-Tibetan Yoga. SUNY Press, 2005, pp. 1–2.

- Tattvarthasutra [6.1], see Manu Doshi (2007) Translation of Tattvarthasutra, Ahmedabad: Shrut Ratnakar p. 102

- Bryant 2009, p. 10.

- Raju 1992, p. 177.

- Sivananda 1993, p. 217.

- King 1999.

- Nicholson 2010.

- Einoo, Shingo (ed.) (2009). Genesis and Development of Tantrism. University of Tokyo. p. 45.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- White 2000, p. 7.

- Harper (2002), p. 2.

- Nikhilanada (1982), pp. 145–160

- Harper (2002), p. 3.

- Kalra, Surjit (2004). Stories Of Guru Nanak. Pitambar Publishing. ISBN 9788120912755.

- Lebron, Robyn (2012). Searching for Spiritual Unity...can There be Common Ground?: A Basic Internet Guide to Forty World Religions & Spiritual Practices. CrossBooks. p. 399. ISBN 9781462712618.

- Sri Guru Granth Sahib. p. Ang 12.

- "The Sikh Review". 57 (7–12). Sikh Cultural Centre. 2009: 35. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sri Guru Granth Sahib. p. Ang 1085.

- Sri Guru Granth Sahib. p. Ang 1237.

- Oliver, P. Mysticism: A Guide for the Perplexed, pp. 47–48

- Harvey 1995.

- Belzen & Geels 2003, p. 7.

- Jones 2016, p. 12.

- Yuichi Kajiyama (1991). Minoru Kiyota and Elvin W. Jones (ed.). Mahāyāna Buddhist Meditation: Theory and Practice. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 120–122, 137–139. ISBN 978-81-208-0760-0.

- Kochumuttom 1999, p. 5.

- King 1995, p. 156.

- Kochumuttom 1999.

- Peter Harvey, Consciousness Mysticism in the Discourses of the Buddha. In Karel Werner, ed., The Yogi and the Mystic. Curzon Press 1989, pages 96–97.

- Dumoulin 2005a.

- Dumoulin 2005b.

- Dumoulin 2005a, p. 168.

- Sekida 1996.

- Kapleau 1989.

- Kraft 1997, p. 91.

- Maezumi & Glassman 2007, p. 54, 140.

- Low 2006.

- Mumon 2004.

- D.T. Suzuki. Mysticism: Christian and Buddhist. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-0-415-28586-5

- Newman 2001, p. 587.

- Harding 1996, p. 16–20.

- Klein 2011, p. 265.

- "Dzogchen - Rigpa Wiki". www.rigpawiki.org.

- Klein & Tenzin Wangyal 2006, p. 4.

- Klein 2011, p. 272.

- Mysticism: A guide for the Perplexed. Oliver, P.

- Richard H. Jones, Philosophy of Mysticism (SUNY Press, 2016), epilogue.

- Stace 1960, p. chap. 1.

- Hood 2003, p. 291.

- Hood 2003, p. 292.

- Stace, Walter (1960). The Teachings of the Mystics. New York: The New American Library. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-451-60306-0.

- Stace, Walter (1960). The Teachings of the Mystics. New York: The New American Library. pp. 15–18. ISBN 0-451-60306-0.

- Stace, Walter (1960). Mysticism and Philosophy. MacMillan. pp. 44–80.

- Moore 2005, p. 6357.

- McMahan 2010, p. 269, note 9.

- Sharf 1995.

- Katz 2000, p. 3.

- Katz 2000, pp. 3–4.

- Jones 2016, chapter 2; also see Jensine Andresen, "Introduction: Towards a Cognitive Science of Religion," in Jensine Andresen, ed., Religion in Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001..

- Proudfoot 1985.

- Newberg & d'Aquili 2008.

- Newberg & Waldman 2009.

- Jones 2016, chapter 4.

- E.g., Richards 2015; Osto 2016

- Picard 2013.

- Devinsky 2003.

- Bryant 1953.

- Leuba 1925.

- Picard 2013, p. 2496–2498.

- Schweitzer 1936

- Danto 1987

- Stace 1960, pp. 323–343.

- Barnard & Kripal 2002.

- Jones 2004.

- King 2002, p. 21.

Sources

Published sources

- Barnard, William G.; Kripal, Jeffrey J., eds. (2002), Crossing Boundaries: Essays on the Ethical Status of Mysticism, Seven Bridges Press

- Belzen, Jacob A.; Geels, Antoon (2003), Mysticism: A Variety of Psychological Perspectives, Rodopi

- Bryant, Ernest J. (1953), Genius and Epilepsy. Brief sketches of Great Men Who Had Both, Concord, Massachusetts: Ye Old Depot PressCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bryant, Edwin (2009), The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali: A New Edition, Translation, and Commentary, New York, USA: North Point Press, ISBN 978-0865477360

- Carrithers, Michael (1983), The Forest Monks of Sri Lanka

- Cobb, W.F. (2009), Mysticism and the Creed, BiblioBazaar, ISBN 978-1-113-20937-5

- Comans, Michael (2000), The Method of Early Advaita Vedānta: A Study of Gauḍapāda, Śaṅkara, Sureśvara, and Padmapāda, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Cook, Brendan (2013), Pursuing Eudaimonia: Re-appropriating the Greek Philosophical Foundations of the Christian Apophatic Tradition, Cambridge Scholars Publishing

- Danto, Arthur C. (1987), Mysticism and Morality, New York: Columbia University Press

- Dasgupta, Surendranath (1975), A History of Indian Philosophy, 1, Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0412-0

- Day, Matthew (2009), Exotic experience and ordinary life. In: Micael Stausberg (ed.)(2009), "Contemporary Theories of Religion", pp. 115–129, Routledge, ISBN 9780203875926

- Devinsky, O. (2003), "Religious experiences and epilepsy", Epilepsy & Behavior, 4 (1): 76–77, doi:10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00680-7, PMID 12609231

- Dewhurst, K.; Beard, A. (2003). "Sudden religious conversions in temporal lobe epilepsy. 1970" (PDF). Epilepsy & Behavior. 4 (1): 78–87. doi:10.1016/S1525-5050(02)00688-1. PMID 12609232. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2006-08-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drvinsky, Julie; Schachter, Steven (2009), "Norman Geschwind's contribution to the understanding of behavioral changes in temporal lobe epilepsy: The February 1974 lecture", Epilepsy & Behavior, 15 (4): 417–424, doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.06.006, PMID 19640791

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005a), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 1: India and China, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-89-1

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005b), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-90-7

- Dupré, Louis (2005), "Mysticism (first edition)", in Jones, Lindsay (ed.), MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religion, MacMillan

- Evans, Donald. (1989), Can Philosophers Limit What Mystics Can Do?, Religious Studies, volume 25, pp. 53–60

- Forman, Robert K., ed. (1997), The Problem of Pure Consciousness: Mysticism and Philosophy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195355116CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Forman, Robert K. (1999), Mysticism, Albany: State University of New York Press

- Geschwind, Markus; Picard, Fabienne (2014), "Ecstatic Epileptic Seizures – the Role of the Insula in Altered Self-Awareness" (PDF), Epileptologie, 31: 87–98, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-09, retrieved 2015-11-03

- Hakuin, Ekaku (2010), Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, Translated by Norman Waddell, Shambhala Publications

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (1996), New Age Religion and Western Culture. Esotericism in the mirror of Secular Thought, Leiden/New York/Koln: E.J. Brill

- Harding, Sarah (1996), Creation and Completion – Essential Points of Tantric Meditation, Boston: Wisdom Publications

- Harmless, William (2007), Mystics, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780198041108

- Harper, Katherine Anne (ed.); Brown, Robert L.(ed.) (2002), The Roots of Tantra, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-5306-5CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Harvey, Peter (1995), An introduction to Buddhism. Teachings, history and practices, Cambridge University Press

- Hisamatsu, Shinʼichi (2002), Critical Sermons of the Zen Tradition: Hisamatsu's Talks on Linji, University of Hawaii Press

- Holmes, Ernest (2010), The Science of Mind: Complete and Unabridged, Wilder Publications, ISBN 978-1604599893

- Horne, James R. (1996), Mysticism and Vocation, Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, ISBN 9780889202641

- Hood, Ralph W. (2003), Mysticism. In: Hood e.a., "The Psychology of Religion. An Empirical Approach", pp 290–340, New York: The Guilford Press

- Hori, Victor Sogen (1994), Teaching and Learning in the Zen Rinzai Monastery. In: Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol.20, No. 1, (Winter, 1994), 5–35 (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-10-25, retrieved 2013-12-06

- Hori, Victor Sogen (1999), Translating the Zen Phrase Book. In: Nanzan Bulletin 23 (1999) (PDF)

- Hori, Victor Sogen (2006), The Steps of Koan Practice. In: John Daido Loori, Thomas Yuho Kirchner (eds), Sitting With Koans: Essential Writings on Zen Koan Introspection, Wisdom Publications

- Hügel, Friedrich, Freiherr von (1908), The Mystical Element of Religion: As Studied in Saint Catherine of Genoa and Her Friends, London: J.M. Dent

- Jacobs, Alan (2004), Advaita and Western Neo-Advaita. In: The Mountain Path Journal, autumn 2004, pages 81–88, Ramanasramam, archived from the original on 2015-05-18, retrieved 2014-10-30

- James, William (1982) [1902], The Varieties of Religious Experience, Penguin classics

- Johnson, William (1997), The Inner Eye of Love: Mysticism and Religion, HarperCollins, ISBN 0-8232-1777-9

- Jones, Richard H. (1983), Mysticism Examined, Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press

- Jones, Richard H. (2004), Mysticism and Morality, Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books

- Jones, Richard H. (2008), Science and Mysticism: A Comparative Study of Western Natural Science, Theravada Buddhism, and Advaita Vedanta, Booksurge Llc, ISBN 9781439203040

- Jones, Richard H. (2016), Philosophy of Mysticism, Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press

- Kapleau, Philip (1989), The Three Pillars of Zen, ISBN 978-0-385-26093-0

- Katz, Steven T. (2000), Mysticism and Sacred Scripture, Oxford University Press

- Kim, Hee-Jin (2007), Dōgen on Meditation and Thinking: A Reflection on His View of Zen, SUNY Press

- King, Richard (1995), Early Advaita Vedānta and Buddhism: The Mahāyāna Context of the Gauḍapādīya-kārikā, SUNY Press

- King, Richard (1999), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

- King, Richard (2002), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

- King, Sallie B. (1988), Two Epistemological Models for the Interpretation of Mysticism, Journal for the American Academy for Religion, volume 26, pp. 257–279

- Klein, Anne Carolyn; Tenzin Wangyal (2006), Unbounded Wholeness : Dzogchen, Bon, and the Logic of the Nonconceptual: Dzogchen, Bon, and the Logic of the Nonconceptual, Oxford University Press

- Klein, Anne Carolyn (2011), Dzogchen. In: Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass (eds.)(2011), The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy, Oxford University Press

- Kochumuttom, Thomas A. (1999), A buddhist Doctrine of Experience. A New Translation and Interpretation of the Works of Vasubandhu the Yogacarin, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Kraft, Kenneth (1997), Eloquent Zen: Daitō and Early Japanese Zen, University of Hawaii Press

- Leuba, J.H. (1925), The psychology of religious mysticism, Harcourt, Brace

- Lewis, James R.; Melton, J. Gordon (1992), Perspectives on the New Age, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1213-X

- Lidke, Jeffrey S. (2005), Interpreting across Mystical Boundaries: An Analysis of Samadhi in the Trika-Kaula Tradition. In: Jacobson (2005), "Theory And Practice of Yoga: Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson", pp 143–180, BRILL, ISBN 9004147578

- Low, Albert (2006), Hakuin on Kensho. The Four Ways of Knowing, Boston & London: Shambhala

- MacInnes, Elaine (2007), The Flowing Bridge: Guidance on Beginning Zen Koans, Wisdom Publications

- Maezumi, Taizan; Glassman, Bernie (2007), The Hazy Moon of Enlightenment, Wisdom Publications

- Magee, Glenn Alexander (2016), The Cambridge Handbook of Western Mysticism and Esotericism, Cambridge University Press

- McGinn, Bernard (2005), "Mystical Union in Judaism, Christianity and Islam", in Jones, Lindsay (ed.), MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religion, MacMillan

- McGinn, Bernard (2006), The Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism, New York: Modern Library

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195183276

- Mohr, Michel (2000), Emerging from Nonduality. Koan Practice in the Rinzai Tradition since Hakuin. In: steven Heine & Dale S. Wright (eds.)(2000), "The Koan. texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism", Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Mooney, Hilary Anne-Marie (2009), Theophany: The Appearing of God According to the Writings of Johannes Scottus Eriugena, Mohr Siebeck

- Moore, Peter (2005), "Mysticism (further considerations)", in Jones, Lindsay (ed.), MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religion, MacMillan

- Moores, D.J. (2006), Mystical Discourse in Wordsworth and Whitman: A Transatlantic Bridge, Peeters Publishers, ISBN 9789042918092

- Mumon, Yamada (2004), Lectures On The Ten Oxherding Pictures, University of Hawaii Press

- Nakamura, Hajime (2004), A History of Early Vedanta Philosophy. Part Two, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

- Newberg, Andrew; d'Aquili, Eugene (2008), Why God Won't Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief, Random House LLC, ISBN 9780307493156

- Newberg, Andrew; Waldman, Mark Robert (2009), How God Changes Your Brain, New York: Ballantine Books

- Newman, John (2001), "Vajrayoga in the Kalachakra Tantra", in White, David Gordon (ed.), Tantra in practice, Motilall Banarsidass

- Nicholson, Andrew J. (2010), Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, Columbia University Press

- Osto, Douglas (2016), Altered States: Buddhism and Psychedelic Spirituality in America, Columbia University Press, ISBN 9780231541411

- Paden, William E. (2009), Comparative religion. In: John Hinnells (ed.)(2009), "The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion", pp. 225–241, Routledge, ISBN 9780203868768

- Parsons, William Barclay (2011), Teaching Mysticism, Oxford University Press

- Picard, Fabienne (2013), "State of belief, subjective certainty and bliss as a product of cortical dysfuntion", Cortex, 49 (9): 2494–2500, doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2013.01.006, PMID 23415878

- Picard, Fabienne; Kurth, Florian (2014), "Ictal alterations of consciousness during ecstatic seizures", Epilepsy & Behavior, 30: 58–61, doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.09.036, PMID 24436968