Fakir

A fakir, faqeer or faqir (/fəˈkɪər/; Arabic: فقیر (noun of faqr)), derived from faqr (Arabic: فقر, "poverty") is an Islamic term traditionally used for a Sufi Muslim whose contingency and utter dependence upon God is manifest in everything they do and every breath they take. They do not necessarily renounce all relationships and take a vow of poverty, some may be poor and some may even be wealthy, but the adornments of the temporal worldly life are kept in perspective and do not detract from their constant neediness of God. The connotations of poverty associated with the term relate to their spiritual neediness, not necessarily their physical neediness.[1][2] The faqir seeks to attain the condition of the perfect slave of Allah, who "delivers his trust (existence) back to its Owner." They are said to be "faqir ila Allah" or impoverished in comparison to Allah, which is the most exalted state to attain.[3][4]

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

List of sufis |

|

|

The term has taken on a more recent and colloqiual usage for an ascetic who renounces worldly possessions, and has even been applied to non-Muslims.[5][6] Faqeers are prevalent in the Middle East and South Asia. A faqeer is thought to be self-sufficient and possesses only the spiritual need for God.[7]

Faqeers are characterized by their reverence for dhikr (a practice of repeating the names of God, often performed after prayers).[8] Sufism gained adherents among a number of Muslims as a reaction against the worldliness of the early Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE[9]). Though, Sufis have spanned several continents and cultures over a millennium, originally expressing their beliefs in Arabic, before spreading into Persian, Turkish, Indian languages and a dozen other languages.[10]

The term is also applied to Hindu ascetics (e.g., sadhus, gurus, swamis and yogis).[11] These usages developed primarily in the Mughal era in the Indian subcontinent.

There is also a distinct clan of faqeers found in North India, descended from communities of faqeers who took up residence at Sufi shrines.

History

| Part of a series on |

| Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

In terms of Ihsan |

|

|

|

Lists |

|

|

During the 17th century, another noble and spirited Muslim scholar and saint, Sultan Bahoo, revolutionized Sufism and reinstated (with fresh properties) the definition of faqr and faqir.

Historically, the terms tasawwuf, faqr, and faqer (noun of faqr) were first used (with full definition) by Husayn ibn Ali, who was the grandson of Muhammad. He wrote a book, Mirat ul Arfeen, on this topic, which is said to be the first book on Sufism and tasawwuf. However, under Ummayad rule, neither could this book be published nor was it allowed to discuss tasawwuf, Sufism or faqr openly. For a long time, after Husayn ibn Ali, the information and teachings of faqr, tasawwuf and Sufism kept on transferring from heart to heart.[12]

In the 10th century, highly reputed Muslim Abdul-Qadir Gilani, who is the founder of Qadri silsila, which has the most followers in Muslim Sufism, elaborated Sufism, tasawwuf and faqr.

In the 13th century, Ibn Arabi was the first vibrant Muslim scholar who not only started this discussion publicly but also wrote hundreds of books about Sufism, tasawwuf and faqr.

In English, faqir or fakir originally meant a mendicant dervish. In mystical usage, the word fakir refers to man's spiritual need for God, who alone is self-sufficient. Although of Muslim origin, the term has come to be applied in India to Hindus as well, largely replacing gosvamin, sadhu, bhikku, and other designations. Fakirs are generally regarded as holy men who are possessed of miraculous powers. Among Muslims, the leading Sufi orders of fakirs are the Shadhiliyyah, Chishtiyah, Qadiriyah, Naqshbandiyah, and Suhrawardiyah.[13]

The Cambridge English Dictionary defines faqir as "a member of an Islamic religious group, or a holy man".[14] Winston Churchill is known to have referred to Mahatma Gandhi, as a "seditious fakir".

Attributes

The attributes of a fakir have been defined by many Muslim scholars.

The early Muslim scholar, Abdul-Qadir Gilani, defined Sufism, tasawwuf and faqr in a conclusive manner. Explaining the attributes of a fakir, he says, "faqir is not who can not do anything and is nothing in his self-being. But faqir has all the commanding powers (gifted from Allah) and his orders can not be revoked."[15][16]

Ibn Arabi explained Sufism, including faqr, in more details. He wrote more than 500 books on the topic. He was the first Muslim scholar to openly introduce (first time openly) the idea of Wahdat al-wujud. His writings are considered a solid source, that defied time.[17][18][19][20]

Another dignified Muslim saint, Sultan Bahoo, describes a fakir as one "who has been entrusted with full authority from Allah (God)". In the same book, Sultan Bahoo says, "Faqir attains eternity by dissolving himself in oneness of Allah. He, when, eliminates himself from other than Allah, his soul reaches to divinity."[21] He says in another book, "faqir has three steps (stages). First step he takes from eternity (without beginning) to this mortal world, second step from this finite world to hereafter and last step he takes from hereafter to manifestation of Allah."[22]

Gurdjieff

In the Fourth Way teaching of G. I. Gurdjieff the word fakir is used to denote the specifically physical path of development, as opposed to the words yogi (which Gurdjieff used for a path of mental development) and monk (which he used for the path of emotional development).[23]

Indian subcontinent

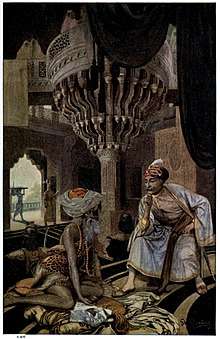

Emperor Jahangir receiving a petition from a fakir.

Emperor Jahangir receiving a petition from a fakir.

The Fakir and Goshai was with the stronger religious influence, and there are even Bauls who would shave their heads as in their past and kept on practicing and believing in many of the basic creeds of Vaishnava-Sahajiya. So all followers of different religions and religious practices came under the nomenclature Baul, which has its etymological origin in the Sanskrit words Vatula ("madcap"), or Vyakula ("restless") and used for someone who is possessed or crazy. They were known as performers 'mad' in a worshiping trance of joy - transcending above both good and bad. Though fond of both Hinduism and Islam, the Baul evolved into a religion focused on the individual and centered on a spiritual quest for God from within. They believe the soul that lives in all human bodies is God.

See also

- Dervish

- Ghous-e-Azam

- Ibn Arabi

- Madariyya

- Mirin Dajo

- Qalandariyya

- Sai Baba of Shirdi

- Shramana

- Sultan Bahoo

- Yogi

- Monk

References

- "Faqīr". Oxford Reference. doi:10.1093/oi/authority.20110810104900321. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Faqir - Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "The Language of the Future | Sufi Terminology - al-faqir ila'llah". www.almirajsuficentre.org.au. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "The Language of the Future | Sufi Terminology". www.almirajsuficentre.org.au. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Dobe, Timothy S. Hindu Christian Faqir: Modern Monks, Global Christianity, and Indian Sainthood. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-934627-1.

- Nanda, B. R. Churchill's ‘Half-naked Faqir’. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-908141-7.

- "Encyclopædia Britannica". britannica.com. Retrieved 2015-07-10.

- A Prayer for Spiritual Elevation and Protection (2007) by Muhyiddin Ibn 'Arabi, Suha Taji-Farouki

- Hawting, Gerald R. (2000). The first dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24073-4. See Google book search.

- Michael Sells, Early Islamic Mysticism, pg. 1

- Colby, Frank Moore; Williams, Talcott (1918). The New International Encyclopaedia. Dodd, Mead. p. 343. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

Fakir: In general a religious mendicant; more specifically a Hindu marvel worker or priestly juggler, usually peripatetic and indigent.

- A brief history of Islam by Tamara Sonn, 2004, p60

- "Online Dictionary / Reference". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- "Dictionary of Cambridge". Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- Biographical encyclopaedia of Sufis: Central Asia and Middle East by N. Hanif, 2002

- The Sultan of the saints: mystical life and teaching of Shaikh Syed Abdul Qadir Jilani, Muhammad Riyāz Qādrī, 2000, p24

- Fusus al-hikam (The Bezels of Wisdom), ed. A. Affifi, Cairo, 1946;trans. R.W.J. Austin, The Bezels of Wisdom, New York: Paulist Press,1980

- al-Futuhat al-makkiyya (The Meccan Illuminations), Cairo, 1911; partial trans. Michel Chodkiewicz et al., Les Illuminations de la Mecque: The Meccan Illuminations, Textes choisis/Selected Texts, Paris: Sindbad,1988.

- The Sufi Path of Knowledge: Ibn al-'Arabi's Metaphysics of Imagination, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.1981

- Sufis of Andalusia, London, George Allen & Unwin.1971

- "Reference from Sultan Bahoo's book". Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- "Noor ul Khuda book of Sultan Bahoo". Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- The Fourth Way: Teachings of G.I. Gurdjieff, P.D. Ouspensky, Random House USA, 2000

External links

| Look up fakir or faqir in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fakirs. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Fakir. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Fakir. |