Babylonian religion

Babylonian religion is the religious practice of Babylonia. Babylonian mythology was greatly influenced by their Sumerian counterparts, and was written on clay tablets inscribed with the cuneiform script derived from Sumerian cuneiform. The myths were usually either written in Sumerian or Akkadian. Some Babylonian texts were translations into Akkadian from the Sumerian language of earlier texts, although the names of some deities were changed.

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

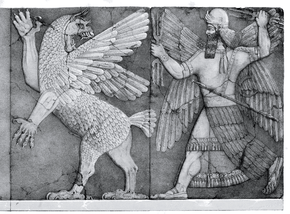

Chaos Monster and Sun God |

|

Seven gods who decree

|

|

Other major deities |

|

Demigods and heroes

|

| Related topics |

| Part of a series on |

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

|---|

Some of the stories of the Tanakh are believed to have been based on, influenced by, or inspired by the legendary mythological past of the Near East.[1]

Mythology and cosmology

Babylonian myths were greatly influenced by the Sumerian religion, and were written on clay tablets inscribed with the cuneiform script derived from Sumerian cuneiform. The myths were usually either written in Sumerian or Akkadian. Some Babylonian texts were even translations into Akkadian from the Sumerian language of earlier texts, although the names of some deities were changed in Babylonian texts.

Many Babylonian deities, myths and religious writings are singular to that culture; for example, the uniquely Babylonian deity, Marduk, replaced Enlil as the head of the mythological pantheon. The Enûma Eliš, a creation myth epic was an original Babylonian work.

Religious festivals

Tablet fragments from the Neo-Babylonian period describe a series of festival days celebrating the New Year. The Festival began on the first day of the first Babylonian month, Nisannu, roughly corresponding to April/May in the Gregorian calendar. This festival celebrated the re-creation of the Earth, drawing from the Marduk-centered creation story described in the Enûma Eliš.[2]

Importance of idols

In Babylonian religion, the ritual care and worship of the statues of deities was considered sacred; the gods lived simultaneously in their statues in temples and in the natural forces they embodied. An elaborate ceremony of washing the mouths of the statues appeared sometime in the Old Babylonian period.

The pillaging or destruction of idols was considered to be loss of divine patronage; during the Neo-Babylonian period, the Chaldean prince Marduk-apla-iddina II fled into the southern marshes of Mesopotamia with the statues of Babylon's gods to save them from the armies of Sennacherib of Assyria.[3]

See also

References

- Morris Jastrow Jr.; et al. "Babylon". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- McIntosh, Jane R. "Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives". ABC-CLIO, Inc: Santa Barbara, California, 2005. p. 221

- McIntosh, Jane R. "Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives". ABC-CLIO, Inc: Santa Barbara, California, 2005. pp. 35-43

Further reading

- Renger, Johannes (1999), "Babylonian and Assyrian Religion", in Fahlbusch, Erwin (ed.), Encyclopedia of Christianity, 1, Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, pp. 177–178, ISBN 0802824137