Meaning of life

The meaning of life, or the answer to the question: "What is the meaning of life?", pertains to the significance of living or existence in general. Many other related questions include: "Why are we here?", "What is life all about?", or "What is the purpose of existence?" There have been many proposed answers to these questions from many different cultural and ideological backgrounds. The search for life's meaning has produced much philosophical, scientific, theological, and metaphysical speculation throughout history. Different people and cultures believe different things for the answer to this question.

The meaning of life as we perceive it is derived from philosophical and religious contemplation of, and scientific inquiries about existence, social ties, consciousness, and happiness. Many other issues are also involved, such as symbolic meaning, ontology, value, purpose, ethics, good and evil, free will, the existence of one or multiple gods, conceptions of God, the soul, and the afterlife. Scientific contributions focus primarily on describing related empirical facts about the universe, exploring the context and parameters concerning the "how" of life. Science also studies and can provide recommendations for the pursuit of well-being and a related conception of morality. An alternative, humanistic approach poses the question, "What is the meaning of my life?"

Questions

Questions about the meaning of life have been expressed in a broad variety of ways, including the following:

- What is the meaning of life? What's it all about? Who are we?[1][2][3]

Philosopher in Meditation (detail) by Rembrandt

Philosopher in Meditation (detail) by Rembrandt - Why are we here? What are we here for?[4][5][6]

- What is the origin of life?[7]

- What is the nature of life? What is the nature of reality?[7][8][9]

- What is the purpose of life? What is the purpose of one's life?[8][10][11]

- What is the significance of life?[11] – see also § Psychological significance and value in life

- What is meaningful and valuable in life?[12]

- What is the value of life?[13]

- What is the reason to live? What are we living for?[6][14]

These questions have resulted in a wide range of competing answers and arguments, from scientific theories, to philosophical, theological, and spiritual explanations.

Scientific inquiry and perspectives

Many members of the scientific community and philosophy of science communities think that science can provide the relevant context, and set of parameters necessary for dealing with topics related to the meaning of life. In their view, science can offer a wide range of insights on topics ranging from the science of happiness to death anxiety. Scientific inquiry facilitates this through nomological investigation into various aspects of life and reality, such as the Big Bang, the origin of life, and evolution, and by studying the objective factors which correlate with the subjective experience of meaning and happiness.

Psychological significance and value in life

Researchers in positive psychology study empirical factors that lead to life satisfaction,[15] full engagement in activities,[16] making a fuller contribution by utilizing one's personal strengths,[17] and meaning based on investing in something larger than the self.[18] Large-data studies of flow experiences have consistently suggested that humans experience meaning and fulfillment when mastering challenging tasks and that the experience comes from the way tasks are approached and performed rather than the particular choice of task. For example, flow experiences can be obtained by prisoners in concentration camps with minimal facilities, and occur only slightly more often in billionaires. A classic example[16] is of two workers on an apparently boring production line in a factory. One treats the work as a tedious chore while the other turns it into a game to see how fast she can make each unit and achieves flow in the process.

Neuroscience describes reward, pleasure, and motivation in terms of neurotransmitter activity, especially in the limbic system and the ventral tegmental area in particular. If one believes that the meaning of life is to maximize pleasure and to ease general life, then this allows normative predictions about how to act to achieve this. Likewise, some ethical naturalists advocate a science of morality—the empirical pursuit of flourishing for all conscious creatures.

Experimental philosophy and neuroethics research collects data about human ethical decisions in controlled scenarios such as trolley problems. It has shown that many types of ethical judgment are universal across cultures, suggesting that they may be innate, whilst others are culture-specific. The findings show actual human ethical reasoning to be at odds with most logical philosophical theories, for example consistently showing distinctions between action by cause and action by omission which would be absent from utility-based theories. Cognitive science has theorized about differences between conservative and liberal ethics and how they may be based on different metaphors from family life such as strong fathers vs nurturing mother models.

Neurotheology is a controversial field which tries to find neural correlates and mechanisms of religious experience. Some researchers have suggested that the human brain has innate mechanisms for such experiences and that living without using them for their evolved purposes may be a cause of imbalance. Studies have reported conflicting results on correlating happiness with religious belief and it is difficult to find unbiased meta-analyses.

Sociology examines value at a social level using theoretical constructs such as value theory, norms, anomie, etc. One value system suggested by social psychologists, broadly called Terror Management Theory, states that human meaning is derived from a fundamental fear of death, and values are selected when they allow us to escape the mental reminder of death.

Alongside this, there are a number of theories about the way in which humans evaluate the positive and negative aspects of their existence and thus the value and meaning they place on their lives. For example, depressive realism posits an exaggerated positivity in all except those experiencing depressive disorders who see life as it truly is, and David Benatar theorises that more weight is generally given to positive experiences, providing bias towards an over-optimistic view of life.

Emerging research shows that meaning in life predicts better physical health outcomes. Greater meaning has been associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease,[19] reduced risk of heart attack among individuals with coronary heart disease,[20] reduced risk of stroke,[21] and increased longevity in both American and Japanese samples.[22] In 2014, the British National Health Service began recommending a five-step plan for mental well-being based on meaningful lives, whose steps are: (1) Connect with community and family; (2) Physical exercise; (3) Lifelong learning; (4) Giving to others; (5) Mindfulness of the world around you.[23]

Origin and nature of biological life

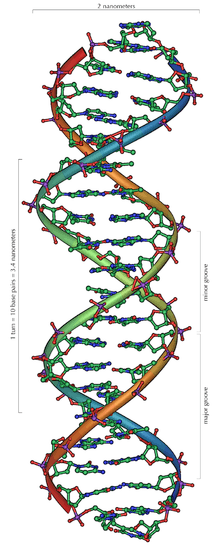

The exact mechanisms of abiogenesis are unknown: notable hypotheses include the RNA world hypothesis (RNA-based replicators) and the iron-sulfur world hypothesis (metabolism without genetics). The process by which different lifeforms have developed throughout history via genetic mutation and natural selection is explained by evolution.[24] At the end of the 20th century, based upon insight gleaned from the gene-centered view of evolution, biologists George C. Williams, Richard Dawkins, and David Haig, among others, concluded that if there is a primary function to life, it is the replication of DNA and the survival of one's genes.[25][26] This view has not achieved universal agreement; Jeremy Griffith is a notable exception, maintaining that the meaning of life is to be integrative.[27] Responding to an interview question from Richard Dawkins about "what it is all for", James Watson stated "I don't think we're for anything. We're just the products of evolution."[28]

Though scientists have intensively studied life on Earth, defining life in unequivocal terms is still a challenge.[29][30] Physically, one may say that life "feeds on negative entropy"[27][31][32] which refers to the process by which living entities decrease their internal entropy at the expense of some form of energy taken in from the environment.[33][34] Biologists generally agree that lifeforms are self-organizing systems which regulate their internal environments as to maintain this organized state, metabolism serves to provide energy, and reproduction causes life to continue over a span of multiple generations. Typically, organisms are responsive to stimuli and genetic information changes from generation to generation, resulting in adaptation through evolution; this optimizes the chances of survival for the individual organism and its descendants respectively.[35]

Non-cellular replicating agents, notably viruses, are generally not considered to be organisms because they are incapable of independent reproduction or metabolism. This classification is problematic, though, since some parasites and endosymbionts are also incapable of independent life. Astrobiology studies the possibility of different forms of life on other worlds, including replicating structures made from materials other than DNA.

Origins and ultimate fate of the universe

Though the Big Bang theory was met with much skepticism when first introduced, it has become well-supported by several independent observations.[36] However, current physics can only describe the early universe from 10−43 seconds after the Big Bang (where zero time corresponds to infinite temperature); a theory of quantum gravity would be required to understand events before that time. Nevertheless, many physicists have speculated about what would have preceded this limit, and how the universe came into being.[37] For example, one interpretation is that the Big Bang occurred coincidentally, and when considering the anthropic principle, it is sometimes interpreted as implying the existence of a multiverse.[38]

The ultimate fate of the universe, and implicitly humanity, is hypothesized as one in which biological life will eventually become unsustainable, such as through a Big Freeze, Big Rip, or Big Crunch.

Theoretical cosmology studies many alternative speculative models for the origin and fate of the universe beyond the Big Bang theory. A recent trend has been models of the creation of 'baby universes' inside black holes, with our own Big Bang being a white hole on the inside of a black hole in another parent universe.[39] Many-worlds theories claim that every possibility of quantum mechanics is played out in parallel universes.

Scientific questions about the mind

The nature and origin of consciousness and the mind itself are also widely debated in science. The explanatory gap is generally equated with the hard problem of consciousness, and the question of free will is also considered to be of fundamental importance. These subjects are mostly addressed in the fields of cognitive science, neuroscience (e.g. the neuroscience of free will) and philosophy of mind, though some evolutionary biologists and theoretical physicists have also made several allusions to the subject.[40][41]

Reductionistic and eliminative materialistic approaches, for example the Multiple Drafts Model, hold that consciousness can be wholly explained by neuroscience through the workings of the brain and its neurons, thus adhering to biological naturalism.[41][42][43]

On the other hand, some scientists, like Andrei Linde, have considered that consciousness, like spacetime, might have its own intrinsic degrees of freedom, and that one's perceptions may be as real as (or even more real than) material objects.[44] Hypotheses of consciousness and spacetime explain consciousness in describing a "space of conscious elements",[44] often encompassing a number of extra dimensions.[45] Electromagnetic theories of consciousness solve the binding problem of consciousness in saying that the electromagnetic field generated by the brain is the actual carrier of conscious experience; there is however disagreement about the implementations of such a theory relating to other workings of the mind.[46][47] Quantum mind theories use quantum theory in explaining certain properties of the mind. Explaining the process of free will through quantum phenomena is a popular alternative to determinism.

Parapsychology

Based on the premises of non-materialistic explanations of the mind, some have suggested the existence of a cosmic consciousness, asserting that consciousness is actually the "ground of all being".[9][48][49] Proponents of this view cite accounts of paranormal phenomena, primarily extrasensory perceptions and psychic powers, as evidence for an incorporeal higher consciousness. In hopes of proving the existence of these phenomena, parapsychologists have orchestrated various experiments, but successful results might be due to poor experimental controls and might have alternative explanations.[50][51][52][53]

Nature of meaning in life

The most common definitions of meaning in life involve three components. First, Reker and Wong define personal meaning as the "cognizance of order, coherence and purpose in one's existence, the pursuit and attainment of worthwhile goals, and an accompanying sense of fulfillment" (p. 221).[54] In 2016 Martela and Steger defined meaning as coherence, purpose, and significance.[55] In contrast, Wong has proposed a four-component solution to the question of meaning in life,[56][57] with the four components purpose, understanding, responsibility, and enjoyment (PURE):

- You need to choose a worthy purpose or a significant life goal.

- You need to have sufficient understanding of who you are, what life demands of you, and how you can play a significant role in life.

- You and you alone are responsible for deciding what kind of life you want to live, and what constitutes a significant and worthwhile life goal.

- You will enjoy a deep sense of significance and satisfaction only when you have exercised your responsibility for self-determination and actively pursue a worthy life-goal.

Thus, a sense of significance permeates every dimension of meaning, rather than stands as a separate factor.

Although most psychology researchers consider meaning in life as a subjective feeling or judgment, most philosophers (e.g., Thaddeus Metz, Daniel Haybron) propose that there are also objective, concrete criteria for what constitutes meaning in life.[58][59] Wong has proposed that whether life is meaningful depends not only on subjective feelings but, more importantly, on whether a person's goal-striving and life as a whole is meaningful according to some objective normative standard.[57]

Western philosophical perspectives

The philosophical perspectives on the meaning of life are those ideologies that explain life in terms of ideals or abstractions defined by humans.

Ancient Greek philosophy

Platonism

Plato, a pupil of Socrates, was one of the earliest, most influential philosophers. His reputation comes from his idealism of believing in the existence of universals. His theory of forms proposes that universals do not physically exist, like objects, but as heavenly forms. In the dialogue of the Republic, the character of Socrates describes the Form of the Good. His theory on justice in the soul relates to the idea of happiness relevant to the question of the meaning of life.

In Platonism, the meaning of life is in attaining the highest form of knowledge, which is the Idea (Form) of the Good, from which all good and just things derive utility and value.

Aristotelianism

Aristotle, an apprentice of Plato, was another early and influential philosopher, who argued that ethical knowledge is not certain knowledge (such as metaphysics and epistemology), but is general knowledge. Because it is not a theoretical discipline, a person had to study and practice in order to become "good"; thus if the person were to become virtuous, he could not simply study what virtue is, he had to be virtuous, via virtuous activities. To do this, Aristotle established what is virtuous:

Every skill and every inquiry, and similarly, every action and choice of action, is thought to have some good as its object. This is why the good has rightly been defined as the object of all endeavor [...]

Everything is done with a goal, and that goal is "good".— Nicomachean Ethics 1.1

Yet, if action A is done towards achieving goal B, then goal B also would have a goal, goal C, and goal C also would have a goal, and so would continue this pattern, until something stopped its infinite regression. Aristotle's solution is the Highest Good, which is desirable for its own sake. It is its own goal. The Highest Good is not desirable for the sake of achieving some other good, and all other "goods" desirable for its sake. This involves achieving eudaemonia, usually translated as "happiness", "well-being", "flourishing", and "excellence".

What is the highest good in all matters of action? To the name, there is an almost complete agreement; for uneducated and educated alike call it happiness, and make happiness identical with the good life and successful living. They disagree, however, about the meaning of happiness.

— Nicomachean Ethics 1.4

Cynicism

Antisthenes, a pupil of Socrates, first outlined the themes of Cynicism, stating that the purpose of life is living a life of Virtue which agrees with Nature. Happiness depends upon being self-sufficient and master of one's mental attitude; suffering is the consequence of false judgments of value, which cause negative emotions and a concomitant vicious character.

The Cynical life rejects conventional desires for wealth, power, health, and fame, by being free of the possessions acquired in pursuing the conventional.[60][61] As reasoning creatures, people could achieve happiness via rigorous training, by living in a way natural to human beings. The world equally belongs to everyone, so suffering is caused by false judgments of what is valuable and what is worthless per the customs and conventions of society.

Cyrenaicism

Aristippus of Cyrene, a pupil of Socrates, founded an early Socratic school that emphasized only one side of Socrates's teachings—that happiness is one of the ends of moral action and that pleasure is the supreme good; thus a hedonistic world view, wherein bodily gratification is more intense than mental pleasure. Cyrenaics prefer immediate gratification to the long-term gain of delayed gratification; denial is unpleasant unhappiness.[62][63]

Epicureanism

Epicurus, a pupil of the Platonist Pamphilus of Samos, taught that the greatest good is in seeking modest pleasures, to attain tranquility and freedom from fear (ataraxia) via knowledge, friendship, and virtuous, temperate living; bodily pain (aponia) is absent through one's knowledge of the workings of the world and of the limits of one's desires. Combined, freedom from pain and freedom from fear are happiness in its highest form. Epicurus' lauded enjoyment of simple pleasures is quasi-ascetic "abstention" from sex and the appetites:

"When we say ... that pleasure is the end and aim, we do not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or the pleasures of sensuality, as we are understood to do, by some, through ignorance, prejudice or willful misrepresentation. By pleasure, we mean the absence of pain in the body and of trouble in the soul. It is not by an unbroken succession of drinking bouts and of revelry, not by sexual lust, nor the enjoyment of fish, and other delicacies of a luxurious table, which produce a pleasant life; it is sober reasoning, searching out the grounds of every choice and avoidance, and banishing those beliefs through which the greatest tumults take possession of the soul."[64]

The Epicurean meaning of life rejects immortality and mysticism; there is a soul, but it is as mortal as the body. There is no afterlife, yet, one need not fear death, because "Death is nothing to us; for that which is dissolved, is without sensation, and that which lacks sensation is nothing to us."[65]

Stoicism

Zeno of Citium, a pupil of Crates of Thebes, established the school which teaches that living according to reason and virtue is to be in harmony with the universe's divine order, entailed by one's recognition of the universal logos, or reason, an essential value of all people. The meaning of life is "freedom from suffering" through apatheia (Gr: απαθεια), that is, being objective and having "clear judgement", not indifference.

Stoicism's prime directives are virtue, reason, and natural law, abided to develop personal self-control and mental fortitude as means of overcoming destructive emotions. The Stoic does not seek to extinguish emotions, only to avoid emotional troubles, by developing clear judgment and inner calm through diligently practiced logic, reflection, and concentration.

The Stoic ethical foundation is that "good lies in the state of the soul", itself, exemplified in wisdom and self-control, thus improving one's spiritual well-being: "Virtue consists in a will which is in agreement with Nature."[65] The principle applies to one's personal relations thus: "to be free from anger, envy, and jealousy".[65]

Enlightenment philosophy

The Enlightenment and the colonial era both changed the nature of European philosophy and exported it worldwide. Devotion and subservience to God were largely replaced by notions of inalienable natural rights and the potentialities of reason, and universal ideals of love and compassion gave way to civic notions of freedom, equality, and citizenship. The meaning of life changed as well, focusing less on humankind's relationship to God and more on the relationship between individuals and their society. This era is filled with theories that equate meaningful existence with the social order.

Classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a set of ideas that arose in the 17th and 18th centuries, out of conflicts between a growing, wealthy, propertied class and the established aristocratic and religious orders that dominated Europe. Liberalism cast humans as beings with inalienable natural rights (including the right to retain the wealth generated by one's own work), and sought out means to balance rights across society. Broadly speaking, it considers individual liberty to be the most important goal,[66] because only through ensured liberty are the other inherent rights protected.

There are many forms and derivations of liberalism, but their central conceptions of the meaning of life trace back to three main ideas. Early thinkers such as John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Adam Smith saw humankind beginning in the state of nature, then finding meaning for existence through labor and property, and using social contracts to create an environment that supports those efforts.

Kantianism

.jpg)

Kantianism is a philosophy based on the ethical, epistemological, and metaphysical works of Immanuel Kant. Kant is known for his deontological theory where there is a single moral obligation, the "Categorical Imperative", derived from the concept of duty. Kantians believe all actions are performed in accordance with some underlying maxim or principle, and for actions to be ethical, they must adhere to the categorical imperative.

Simply put, the test is that one must universalize the maxim (imagine that all people acted in this way) and then see if it would still be possible to perform the maxim in the world without contradiction. In Groundwork, Kant gives the example of a person who seeks to borrow money without intending to pay it back. This is a contradiction because if it were a universal action, no person would lend money anymore as he knows that he will never be paid back. The maxim of this action, says Kant, results in a contradiction in conceivability (and thus contradicts perfect duty).

Kant also denied that the consequences of an act in any way contribute to the moral worth of that act, his reasoning being that the physical world is outside one's full control and thus one cannot be held accountable for the events that occur in it.

19th-century philosophy

Utilitarianism

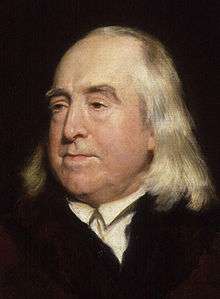

The origins of utilitarianism can be traced back as far as Epicurus, but, as a school of thought, it is credited to Jeremy Bentham,[67] who found that "nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure"; then, from that moral insight, he derived the Rule of Utility: "that the good is whatever brings the greatest happiness to the greatest number of people". He defined the meaning of life as the "greatest happiness principle".

Jeremy Bentham's foremost proponent was James Mill, a significant philosopher in his day, and father of John Stuart Mill. The younger Mill was educated per Bentham's principles, including transcribing and summarizing much of his father's work.[68]

Nihilism

Nihilism suggests that life is without objective meaning.

Friedrich Nietzsche characterized nihilism as emptying the world, and especially human existence, of meaning, purpose, comprehensible truth, and essential value; succinctly, nihilism is the process of "the devaluing of the highest values".[69] Seeing the nihilist as a natural result of the idea that God is dead, and insisting it was something to overcome, his questioning of the nihilist's life-negating values returned meaning to the Earth.[70]

To Martin Heidegger, nihilism is the movement whereby "being" is forgotten, and is transformed into value, in other words, the reduction of being to exchange value.[69] Heidegger, in accordance with Nietzsche, saw in the so-called "death of God" a potential source for nihilism:

If God, as the supra-sensory ground and goal, of all reality, is dead; if the supra-sensory world of the Ideas has suffered the loss of its obligatory, and above it, its vitalizing and up-building power, then nothing more remains to which Man can cling, and by which he can orient himself.[71]

The French philosopher Albert Camus asserts that the absurdity of the human condition is that people search for external values and meaning in a world which has none and is indifferent to them. Camus writes of value-nihilists such as Meursault,[72] but also of values in a nihilistic world, that people can instead strive to be "heroic nihilists", living with dignity in the face of absurdity, living with "secular saintliness", fraternal solidarity, and rebelling against and transcending the world's indifference.[73]

20th-century philosophy

The current era has seen radical changes in both formal and popular conceptions of human nature. The knowledge disclosed by modern science has effectively rewritten the relationship of humankind to the natural world. Advances in medicine and technology have freed humans from significant limitations and ailments of previous eras;[74] and philosophy—particularly following the linguistic turn—has altered how the relationships people have with themselves and each other are conceived. Questions about the meaning of life have also seen radical changes, from attempts to reevaluate human existence in biological and scientific terms (as in pragmatism and logical positivism) to efforts to meta-theorize about meaning-making as a personal, individual-driven activity (existentialism, secular humanism).

Pragmatism

Pragmatism originated in the late-19th-century US, concerning itself (mostly) with truth, and positing that "only in struggling with the environment" do data, and derived theories, have meaning, and that consequences, like utility and practicality, are also components of truth. Moreover, pragmatism posits that anything useful and practical is not always true, arguing that what most contributes to the most human good in the long course is true. In practice, theoretical claims must be practically verifiable, i.e. one should be able to predict and test claims, and, that, ultimately, the needs of humankind should guide human intellectual inquiry.

Pragmatic philosophers suggest that the practical, useful understanding of life is more important than searching for an impractical abstract truth about life. William James argued that truth could be made, but not sought.[75][76] To a pragmatist, the meaning of life is discoverable only via experience.

Theism

Theists believe God created the universe and that God had a purpose in doing so. Theists also hold the view that humans find their meaning and purpose for life in God's purpose in creating. Theists further hold that if there were no God to give life ultimate meaning, value, and purpose, then life would be absurd.[77]

Existentialism

According to existentialism, each man and each woman creates the essence (meaning) of their life; life is not determined by a supernatural god or an earthly authority, one is free. As such, one's ethical prime directives are action, freedom, and decision, thus, existentialism opposes rationalism and positivism. In seeking meaning to life, the existentialist looks to where people find meaning in life, in course of which using only reason as a source of meaning is insufficient; this gives rise to the emotions of anxiety and dread, felt in considering one's free will, and the concomitant awareness of death. According to Jean-Paul Sartre, existence precedes essence; the (essence) of one's life arises only after one comes to existence.

Søren Kierkegaard spoke about a "leap", arguing that life is full of absurdity, and one must make his and her own values in an indifferent world. One can live meaningfully (free of despair and anxiety) in an unconditional commitment to something finite and devotes that meaningful life to the commitment, despite the vulnerability inherent to doing so.[78]

Arthur Schopenhauer answered: "What is the meaning of life?" by stating that one's life reflects one's will, and that the will (life) is an aimless, irrational, and painful drive. Salvation, deliverance, and escape from suffering are in aesthetic contemplation, sympathy for others, and asceticism.[79][80]

For Friedrich Nietzsche, life is worth living only if there are goals inspiring one to live. Accordingly, he saw nihilism ("all that happens is meaningless") as without goals. He stated that asceticism denies one's living in the world; stated that values are not objective facts, that are rationally necessary, universally binding commitments: our evaluations are interpretations, and not reflections of the world, as it is, in itself, and, therefore, all ideations take place from a particular perspective.[70]

Absurdism

Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death[81]

In absurdist philosophy, the Absurd arises out of the fundamental disharmony between the individual's search for meaning and the apparent meaninglessness of the universe. As beings looking for meaning in a meaningless world, humans have three ways of resolving the dilemma. Kierkegaard and Camus describe the solutions in their works, The Sickness Unto Death (1849) and The Myth of Sisyphus (1942):

- Suicide (or, "escaping existence"): a solution in which a person simply ends one's own life. Both Kierkegaard and Camus dismiss the viability of this option.

- Religious belief in a transcendent realm or being: a solution in which one believes in the existence of a reality that is beyond the Absurd, and, as such, has meaning. Kierkegaard stated that a belief in anything beyond the Absurd requires a non-rational but perhaps necessary religious acceptance in such an intangible and empirically unprovable thing (now commonly referred to as a "leap of faith"). However, Camus regarded this solution as "philosophical suicide".

- Acceptance of the Absurd: a solution in which one accepts and even embraces the Absurd and continues to live in spite of it. Camus endorsed this solution (notably in his 1947 allegorical novel The Plague or La Peste), while Kierkegaard regarded this solution as "demoniac madness": "He rages most of all at the thought that eternity might get it into its head to take his misery from him!"[82]

Secular humanism

Per secular humanism, the human species came to be by reproducing successive generations in a progression of unguided evolution as an integral expression of nature, which is self-existing.[83][84] Human knowledge comes from human observation, experimentation, and rational analysis (the scientific method), and not from supernatural sources; the nature of the universe is what people discern it to be.[83] Likewise, "values and realities" are determined "by means of intelligent inquiry"[83] and "are derived from human need and interest as tested by experience", that is, by critical intelligence.[85][86] "As far as we know, the total personality is [a function] of the biological organism transacting in a social and cultural context."[84]

People determine human purpose without supernatural influence; it is the human personality (general sense) that is the purpose of a human being's life. Humanism seeks to develop and fulfill:[83] "Humanism affirms our ability and responsibility to lead ethical lives of personal fulfillment that aspire to the greater good of humanity".[85] Humanism aims to promote enlightened self-interest and the common good for all people. It is based on the premises that the happiness of the individual person is inextricably linked to the well-being of all humanity, in part because humans are social animals who find meaning in personal relations and because cultural progress benefits everybody living in the culture.[84][85]

The philosophical subgenres posthumanism and transhumanism (sometimes used synonymously) are extensions of humanistic values. One should seek the advancement of humanity and of all life to the greatest degree feasible and seek to reconcile Renaissance humanism with the 21st century's technoscientific culture. In this light, every living creature has the right to determine its personal and social "meaning of life".[87]

From a humanism-psychotherapeutic point of view, the question of the meaning of life could be reinterpreted as "What is the meaning of my life?"[88] This approach emphasizes that the question is personal—and avoids focusing on cosmic or religious questions about overarching purpose. There are many therapeutic responses to this question. For example, Viktor Frankl argues for "Dereflection", which translates largely as cease endlessly reflecting on the self; instead, engage in life. On the whole, the therapeutic response is that the question itself—what is the meaning of life?—evaporates when one is fully engaged in life. (The question then morphs into more specific worries such as "What delusions am I under?"; "What is blocking my ability to enjoy things?"; "Why do I neglect loved-ones?".) See also: Existential Therapy and Irvin Yalom

Logical positivism

Logical positivists ask: "What is the meaning of life?", "What is the meaning in asking?"[89][90] and "If there are no objective values, then, is life meaningless?"[91] Ludwig Wittgenstein and the logical positivists said: "Expressed in language, the question is meaningless"; because, in life the statement the "meaning of x", usually denotes the consequences of x, or the significance of x, or what is notable about x, etc., thus, when the meaning of life concept equals "x", in the statement the "meaning of x", the statement becomes recursive, and, therefore, nonsensical, or it might refer to the fact that biological life is essential to having a meaning in life.

The things (people, events) in the life of a person can have meaning (importance) as parts of a whole, but a discrete meaning of (the) life, itself, aside from those things, cannot be discerned. A person's life has meaning (for themselves, others) as the life events resulting from their achievements, legacy, family, etc., but, to say that life, itself, has meaning, is a misuse of language, since any note of significance, or of consequence, is relevant only in life (to the living), so rendering the statement erroneous. Bertrand Russell wrote that although he found that his distaste for torture was not like his distaste for broccoli, he found no satisfactory, empirical method of proving this:[65]

When we try to be definite, as to what we mean when we say that this or that is "the Good," we find ourselves involved in very great difficulties. Bentham's creed, that pleasure is the Good, roused furious opposition, and was said to be a pig's philosophy. Neither he nor his opponents could advance any argument. In a scientific question, evidence can be adduced on both sides, and, in the end, one side is seen to have the better case—or, if this does not happen, the question is left undecided. But in a question, as to whether this, or that, is the ultimate Good, there is no evidence, either way; each disputant can only appeal to his own emotions, and employ such rhetorical devices as shall arouse similar emotions in others ... Questions as to "values"—that is to say, as to what is good or bad on its own account, independently of its effects—lie outside the domain of science, as the defenders of religion emphatically assert. I think that, in this, they are right, but, I draw the further conclusion, which they do not draw, that questions as to "values" lie wholly outside the domain of knowledge. That is to say, when we assert that this, or that, has "value", we are giving expression to our own emotions, not to a fact, which would still be true if our personal feelings were different.[92]

Postmodernism

Postmodernist thought—broadly speaking—sees human nature as constructed by language, or by structures and institutions of human society. Unlike other forms of philosophy, postmodernism rarely seeks out a priori or innate meanings in human existence, but instead focuses on analyzing or critiquing given meanings in order to rationalize or reconstruct them. Anything resembling a "meaning of life", in postmodernist terms, can only be understood within a social and linguistic framework and must be pursued as an escape from the power structures that are already embedded in all forms of speech and interaction. As a rule, postmodernists see awareness of the constraints of language as necessary to escaping those constraints, but different theorists take different views on the nature of this process: from a radical reconstruction of meaning by individuals (as in deconstructionism) to theories in which individuals are primarily extensions of language and society, without real autonomy (as in poststructuralism).

Naturalistic pantheism

According to naturalistic pantheism, the meaning of life is to care for and look after nature and the environment.

Embodied cognition

Embodied cognition uses the neurological basis of emotion, speech, and cognition to understand the nature of thought. Cognitive neuropsychology has identified brain areas necessary for these abilities, and genetic studies show that the gene FOXP2 affects neuroplasticity which underlies language fluency. George Lakoff, a professor of cognitive linguistics and philosophy, advances the view that metaphors are the usual basis of meaning, not the logic of verbal symbol manipulation. Computers use logic programming to effectively query databases but humans rely on a trained biological neural network. Postmodern philosophies that use the indeterminacy of symbolic language to deny definite meaning ignore those who feel they know what they mean and feel that their interlocutors know what they mean. Choosing the correct metaphor results in enough common understanding to pursue questions such as the meaning of life. Improved knowledge of brain function should result in better treatments producing healthier brains. When combined with more effective training, a sound personal assessment as to the meaning of one's life should be straightforward.

East Asian philosophical perspectives

Mohism

The Mohist philosophers believed that the purpose of life was universal, impartial love. Mohism promoted a philosophy of impartial caring—a person should care equally for all other individuals, regardless of their actual relationship to him or her.[93] The expression of this indiscriminate caring is what makes a man a righteous being in Mohist thought. This advocacy of impartiality was a target of attack by the other Chinese philosophical schools, most notably the Confucians who believed that while love should be unconditional, it should not be indiscriminate. For example, children should hold a greater love for their parents than for random strangers.

Confucianism

Confucianism recognizes human nature in accordance with the need for discipline and education. Because humankind is driven by both positive and negative influences, Confucianists see a goal in achieving virtue through strong relationships and reasoning as well as minimizing the negative. This emphasis on normal living is seen in the Confucianist scholar Tu Wei-Ming's quote, "we can realize the ultimate meaning of life in ordinary human existence."[94]

Legalism

The Legalists believed that finding the purpose of life was a meaningless effort. To the Legalists, only practical knowledge was valuable, especially as it related to the function and performance of the state.

Religious perspectives

The religious perspectives on the meaning of life are those ideologies that explain life in terms of an implicit purpose not defined by humans. According to the Charter for Compassion, signed by many of the world's leading religious and secular organizations, the core of religion is the golden rule of 'treat others as you would have them treat you'. The Charter's founder, Karen Armstrong, quotes the ancient Rabbi Hillel who suggested that 'the rest is commentary'. This is not to reduce the commentary's importance, and Armstrong considers that its study, interpretation, and ritual are the means by which religious people internalize and live the golden rule.

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

In the Judaic world view, the meaning of life is to elevate the physical world ('Olam HaZeh') and prepare it for the world to come ('Olam HaBa'), the messianic era. This is called Tikkun Olam ("Fixing the World"). Olam HaBa can also mean the spiritual afterlife, and there is debate concerning the eschatological order. However, Judaism is not focused on personal salvation, but on communal (between man and man) and individual (between man and God) spiritualised actions in this world.

Judaism's most important feature is the worship of a single, incomprehensible, transcendent, one, indivisible, absolute Being, who created and governs the universe. Closeness with the God of Israel is through a study of His Torah, and adherence to its mitzvot (divine laws). In traditional Judaism, God established a special covenant with a people, the people of Israel, at Mount Sinai, giving the Jewish commandments. Torah comprises the written Pentateuch and the transcribed oral tradition, further developed through the generations. The Jewish people are intended as "a kingdom of priests and a holy nation"[95] and a "light to the Nations", influencing the other peoples to keep their own religio-ethical Seven Laws of Noah. The messianic era is seen as the perfection of this dual path to God.

Jewish observances involve ethical and ritual, affirmative, and prohibitive injunctions. Modern Jewish denominations differ over the nature, relevance, and emphases of mitzvot. Jewish philosophy emphasises that God is not affected or benefited, but the individual and society benefit by drawing close to God. The rationalist Maimonides sees the ethical and ritual divine commandments as a necessary, but insufficient preparation for philosophical understanding of God, with its love and awe.[96] Among fundamental values in the Torah are pursuit of justice, compassion, peace, kindness, hard work, prosperity, humility, and education.[97][98] The world to come,[99] prepared in the present, elevates man to an everlasting connection with God.[100] Simeon the Righteous says, "the world stands on three things: on Torah, on worship, and on acts of loving kindness." The prayer book relates, "blessed is our God who created us for his honor...and planted within us everlasting life." Of this context, the Talmud states, "everything that God does is for the good," including suffering.

The Jewish mystical Kabbalah gives complementary esoteric meanings of life. As well as Judaism providing an immanent relationship with God (personal theism), in Kabbalah the spiritual and physical creation is a paradoxical manifestation of the immanent aspects of God's Being (panentheism), related to the Shekhinah (Divine feminine). Jewish observance unites the sephirot (Divine attributes) on high, restoring harmony to creation. In Lurianic Kabbalah, the meaning of life is the messianic rectification of the shattered sparks of God's persona, exiled in physical existence (the Kelipot shells), through the actions of Jewish observance.[101] Through this, in Hasidic Judaism the ultimate essential "desire" of God is the revelation of the Omnipresent Divine essence through materiality, achieved by a man from within his limited physical realm when the body will give life to the soul.[102]

Christianity

Christianity has its roots in Judaism, and shares much of the latter faith's ontology. Its central beliefs derive from the teachings of Jesus Christ as presented in the New Testament. Life's purpose in Christianity is to seek divine salvation through the grace of God and intercession of Christ (John 11:26). The New Testament speaks of God wanting to have a relationship with humans both in this life and the life to come, which can happen only if one's sins are forgiven (John 3:16–21; 2 Peter 3:9).

In the Christian view, humankind was made in the Image of God and perfect, but the Fall of Man caused the progeny of the first Parents to inherit Original Sin and its consequences. Christ's passion, death and resurrection provide the means for transcending that impure state (Romans 6:23). The good news that this restoration from sin is now possible is called the gospel. The specific process of appropriating salvation through Christ and maintaining a relationship with God varies between different denominations of Christians, but all rely on faith in Christ and the gospel as the fundamental starting point. Salvation through faith in God is found in Ephesians 2:8–9 – "[8]For by grace you have been saved through faith; and that not of yourselves, it is the gift of God; [9]not as a result of works, that no one should boast" (NASB; 1973). The gospel maintains that through this belief, the barrier that sin has created between man and God is destroyed, thereby allowing God to regenerate (change) the believer and instill in them a new heart after God's own will with the ability to live righteously before him. This is what the terms Born again or saved almost always refer to.

In the Westminster Shorter Catechism, the first question is: "What is the chief end of Man?" (that is, "What is Man's main purpose?"). The answer is: "Man's chief end is to glorify God, and enjoy him forever". God requires one to obey the revealed moral law, saying: "love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbour as yourself".[104] The Baltimore Catechism answers the question "Why did God make you?" by saying "God made me to know Him, to love Him, and to serve Him in this world, and to be happy with Him forever in heaven."[105]

The Apostle Paul also answers this question in his speech on the Areopagus in Athens: "And He has made from one blood every nation of men to dwell on all the face of the earth, and has determined their preappointed times and the boundaries of their dwellings, so that they should seek the Lord, in the hope that they might grope for Him and find Him, though He is not far from each one of us."[106]

Catholicism's way of thinking is better expressed through the Principle and Foundation of St. Ignatius of Loyola: "The human person is created to praise, reverence, and serve God Our Lord, and by doing so, to save his or her soul. All other things on the face of the earth are created for human beings in order to help them pursue the end for which they are created. It follows from this that one must use other created things, in so far as they help towards one's end, and free oneself from them, in so far as they are obstacles to one's end. To do this, we need to make ourselves indifferent to all created things, provided the matter is subject to our free choice and there is no other prohibition. Thus, as far as we are concerned, we should not want health more than illness, wealth more than poverty, fame more than disgrace, a-long life more than a short one, and similarly for all the rest, but we should desire and choose only what helps us more towards the end for which we are created."[107]

Mormonism teaches that the purpose of life on Earth is to gain knowledge and experience and to have joy.[108] Mormons believe that humans are literally the spirit children of God the Father, and thus have the potential to progress to become like Him. Mormons teach that God provided his children the choice to come to Earth, which is considered a crucial stage in their development—wherein a mortal body, coupled with the freedom to choose, makes for an environment to learn and grow.[108] The Fall of Adam is not viewed as an unfortunate or unplanned cancellation of God's original plan for a paradise; rather, the opposition found in mortality is an essential element of God's plan because the process of enduring and overcoming challenges, difficulties, and temptations provides opportunities to gain wisdom and strength, thereby learning to appreciate and choose good and reject evil.[109][110] Because God is just, he allows those who were not taught the gospel during mortality to receive it after death in the spirit world,[111] so that all of his children have the opportunity to return to live with God, and reach their full potential.

A recent alternative Christian theological discourse interprets Jesus as revealing that the purpose of life is to elevate our compassionate response to human suffering;[112] nonetheless, the conventional Christian position is that people are justified by belief in the propitiatory sacrifice of Jesus' death on the cross.

Islam

In Islam, humanity's ultimate purpose is to worship their creator, Allah (English: The God), through his signs, and be grateful to him through sincere love and devotion. This is practically shown by following the divine guidelines revealed in the Qur'an and the tradition of the Prophet (for non-koranist). Earthly life is a test, determining one's position of closeness to Allah in the hereafter. A person will either be close to him and his love in Jannah (Paradise) or far away in Jahannam (Hell).

For Allah's satisfaction, via the Qur'an, all Muslims must believe in God, his revelations, his angels, his messengers, and in the "Day of Judgment".[113] The Qur'an describes the purpose of creation as follows: "Blessed be he in whose hand is the kingdom, he is powerful over all things, who created death and life that he might examine which of you is best in deeds, and he is the almighty, the forgiving" (Qur'an 67:1–2) and "And I (Allâh) created not the jinn and mankind except that they should be obedient (to Allah)." (Qur'an 51:56). Obedience testifies to the oneness of God in his lordship, his names, and his attributes. Terrenal life is a test; how one acts (behaves) determines whether one's soul goes to Jannat (Heaven) or to Jahannam (Hell).[114] However, on the day of Judgement the final decision is of Allah alone.[115]

The Five Pillars of Islam are duties incumbent to every Muslim; they are: Shahadah (profession of faith); salat (ritual prayer); Zakah (charity); Sawm (fasting during Ramadan), and Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca).[116] They derive from the Hadith works, notably of Sahih Al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim. The five pillars are not mentioned directly in the Quran.

Beliefs differ among the Kalam. The Sunni and the Ahmadiyya concept of pre-destination is divine decree;[117] likewise, the Shi'a concept of pre-destination is divine justice; in the esoteric view of the Sufis, the universe exists only for God's pleasure; Creation is a grand game, wherein Allah is the greatest prize.

The Sufi view of the meaning of life stems from the hadith qudsi that states "I (God) was a Hidden Treasure and loved to be known. Therefore I created the Creation that I might be known." One possible interpretation of this view is that the meaning of life for an individual is to know the nature of God, and the purpose of all of creation is to reveal that nature and to prove its value as the ultimate treasure, that is God. However, this hadith is stated in various forms and interpreted in various ways by people, such, as 'Abdu'l-Bahá of the Bahá'í Faith,[118] and in Ibn'Arabī's Fuṣūṣ al-Ḥikam.[119]

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í Faith emphasizes the unity of humanity.[120] To Bahá'ís, the purpose of life is focused on spiritual growth and service to humanity. Human beings are viewed as intrinsically spiritual beings. People's lives in this material world provide extended opportunities to grow, to develop divine qualities and virtues, and the prophets were sent by God to facilitate this.[121][122]

South Asian religions

Hindu philosophies

Hinduism is a religious category including many beliefs and traditions. Since Hinduism was the way of expressing meaningful living for a long time, before there was a need for naming it as a separate religion, Hindu doctrines are supplementary and complementary in nature, generally non-exclusive, suggestive and tolerant in content.[123] Most believe that the ātman (spirit, soul)—the person's true self—is eternal.[124] In part, this stems from Hindu beliefs that spiritual development occurs across many lifetimes, and goals should match the state of development of the individual. There are four possible aims to human life, known as the purusharthas (ordered from least to greatest): (i)Kāma (wish, desire, love and sensual pleasure), (ii)Artha (wealth, prosperity, glory), (iii)Dharma (righteousness, duty, morality, virtue, ethics), encompassing notions such as ahimsa (non-violence) and satya (truth) and (iv)Moksha (liberation, i.e. liberation from Saṃsāra, the cycle of reincarnation).[125][126][127]

In all schools of Hinduism, the meaning of life is tied up in the concepts of karma (causal action), sansara (the cycle of birth and rebirth), and moksha (liberation). Existence is conceived as the progression of the ātman (similar to the western concept of a soul) across numerous lifetimes, and its ultimate progression towards liberation from karma. Particular goals for life are generally subsumed under broader yogas (practices) or dharma (correct living) which are intended to create more favorable reincarnations, though they are generally positive acts in this life as well. Traditional schools of Hinduism often worship Devas which are manifestations of Ishvara (a personal or chosen God); these Devas are taken as ideal forms to be identified with, as a form of spiritual improvement.

In short, the goal is to realize the fundamental truth about oneself. This thought is conveyed in the Mahāvākyas ("Tat Tvam Asi" (thou art that), "Aham Brahmāsmi", "Prajñānam Brahma" and "Ayam Ātmā Brahma" (the soul and the world are one)).

Advaita and Dvaita Hinduism

Later schools reinterpreted the vedas to focus on Brahman, "The One Without a Second",[128] as a central God-like figure.

In monist Advaita Vedanta, ātman is ultimately indistinguishable from Brahman, and the goal of life is to know or realize that one's ātman (soul) is identical to Brahman.[129] To the Upanishads, whoever becomes fully aware of the ātman, as one's core of self, realizes identity with Brahman, and, thereby, achieves Moksha (liberation, freedom).[124][130][131]

Dvaita Vedanta and other bhakti schools have a dualist interpretation. Brahman is seen as a supreme being with a personality and manifest qualities. The ātman depends upon Brahman for its existence; the meaning of life is achieving Moksha through the love of God and upon His grace.[130]

Vaishnavism

Vaishnavism is a branch of Hinduism in which the principal belief is the identification of Vishnu or Narayana as the one supreme God. This belief contrasts with the Krishna-centered traditions, such as Vallabha, Nimbaraka and Gaudiya, in which Krishna is considered to be the One and only Supreme God and the source of all avataras.[132]

Vaishnava theology includes the central beliefs of Hinduism such as monotheism, reincarnation, samsara, karma, and the various Yoga systems, but with a particular emphasis on devotion (bhakti) to Vishnu through the process of Bhakti yoga, often including singing Vishnu's name's (bhajan), meditating upon his form (dharana) and performing deity worship (puja). The practices of deity worship are primarily based on texts such as Pañcaratra and various Samhitas.[133]

One popular school of thought, Gaudiya Vaishnavism, teaches the concept of Achintya Bheda Abheda. In this, Krishna is worshipped as the single true God, and all living entities are eternal parts and the Supreme Personality of the Godhead Krishna. Thus the constitutional position of a living entity is to serve the Lord with love and devotion. The purpose of human life especially is to think beyond the animalistic way of eating, sleeping, mating, and defending and engage the higher intelligence to revive the lost relationship with Krishna.

Jainism

Jainism is a religion originating in ancient India, its ethical system promotes self-discipline above all else. Through following the ascetic teachings of Jina, a human achieves enlightenment (perfect knowledge). Jainism divides the universe into living and non-living beings. Only when the living becomes attached to the non-living does suffering result. Therefore, happiness is the result of self-conquest and freedom from external objects. The meaning of life may then be said to be to use the physical body to achieve self-realization and bliss.[134]

Jains believe that every human is responsible for his or her actions and all living beings have an eternal soul, jiva. Jains believe all souls are equal because they all possess the potential of being liberated and attaining Moksha. The Jain view of karma is that every action, every word, every thought produces, besides its visible, and invisible, the transcendental effect on the soul.

Jainism includes strict adherence to ahimsa (or ahinsā), a form of nonviolence that goes far beyond vegetarianism. Jains refuse food obtained with unnecessary cruelty. Many practice a lifestyle similar to veganism due to the violence of modern dairy farms, and others exclude root vegetables from their diets in order to preserve the lives of the plants from which they eat.[135]

Buddhism

Earlier Buddhism

Buddhists practice embracing mindfulness the ill-being (suffering) and well-being that is present in life. Buddhists practice seeing the causes of ill-being and well-being in life. For example, one of the causes of suffering is an unhealthy attachment to objects material or non-material. The Buddhist sūtras and tantras do not speak about "the meaning of life" or "the purpose of life", but about the potential of human life to end suffering, for example through embracing (not suppressing or denying) cravings and conceptual attachments. Attaining and perfecting dispassion is a process of many levels that ultimately results in the state of Nirvana. Nirvana means freedom from both suffering and rebirth.[136]

Theravada Buddhism is generally considered to be close to the early Buddhist practice. It promotes the concept of Vibhajjavada (Pali), literally "Teaching of Analysis", which says that insight must come from the aspirant's experience, critical investigation, and reasoning instead of by blind faith. However, the Theravadin tradition also emphasizes heeding the advice of the wise, considering such advice and evaluation of one's own experiences to be the two tests by which practices should be judged. The Theravadin goal is liberation (or freedom) from suffering, according to the Four Noble Truths. This is attained in the achievement of Nirvana, or Unbinding which also ends the repeated cycle of birth, old age, sickness, and death. The way to attain Nirvana is by following and practicing the Noble Eightfold Path.

Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhist schools de-emphasize the traditional view (still practiced in Theravada) of the release from individual Suffering (Dukkha) and attainment of Awakening (Nirvana). In Mahayana, the Buddha is seen as an eternal, immutable, inconceivable, omnipresent being. The fundamental principles of Mahayana doctrine are based on the possibility of universal liberation from suffering for all beings, and the existence of the transcendent Buddha-nature, which is the eternal Buddha essence present, but hidden and unrecognised, in all living beings.

Philosophical schools of Mahayana Buddhism, such as Chan/Zen and the vajrayana Tibetan and Shingon schools, explicitly teach that bodhisattvas should refrain from full liberation, allowing themselves to be reincarnated into the world until all beings achieve enlightenment. Devotional schools such as Pure Land Buddhism seek the aid of celestial buddhas—individuals who have spent lifetimes accumulating positive karma, and use that accumulation to aid all.

Sikhism

The followers of Sikhism are ordained to follow the teachings of the ten Sikh Gurus, or enlightened leaders, as well as the holy scripture entitled the Gurū Granth Sāhib, which includes selected works of many philosophers from diverse socio-economic and religious backgrounds.

The Sikh Gurus say that salvation can be obtained by following various spiritual paths, so Sikhs do not have a monopoly on salvation: "The Lord dwells in every heart, and every heart has its own way to reach Him."[137] Sikhs believe that all people are equally important before God.[138] Sikhs balance their moral and spiritual values with the quest for knowledge, and they aim to promote a life of peace and equality but also of positive action.[139]

A key distinctive feature of Sikhism is a non-anthropomorphic concept of God, to the extent that one can interpret God as the Universe itself (pantheism). Sikhism thus sees life as an opportunity to understand this God as well as to discover the divinity which lies in each individual. While a full understanding of God is beyond human beings,[140] Nanak described God as not wholly unknowable, and stressed that God must be seen from "the inward eye", or the "heart", of a human being: devotees must meditate to progress towards enlightenment and the ultimate destination of a Sikh is to lose the ego completely in the love of the lord and finally merge into the almighty creator. Nanak emphasized the revelation through meditation, as its rigorous application permits the existence of communication between God and human beings.[140]

East Asian religions

Taoism

Taoist cosmogony emphasizes the need for all sentient beings and all men to return to the primordial or to rejoin with the Oneness of the Universe by way of self-cultivation and self-realization. All adherents should understand and be in tune with the ultimate truth.

Taoists believe all things were originally from Taiji and Tao, and the meaning in life for the adherents is to realize the temporal nature of the existence. "Only introspection can then help us to find our innermost reasons for living ... the simple answer is here within ourselves."[141]

Shinto

Shinto is the native religion of Japan. Shinto means "the path of the kami", but more specifically, it can be taken to mean "the divine crossroad where the kami chooses his way". The "divine" crossroad signifies that all the universe is divine spirit. This foundation of free will, choosing one's way, means that life is a creative process.

Shinto wants life to live, not to die. Shinto sees death as pollution and regards life as the realm where the divine spirit seeks to purify itself by rightful self-development. Shinto wants individual human life to be prolonged forever on earth as a victory of the divine spirit in preserving its objective personality in its highest forms. The presence of evil in the world, as conceived by Shinto, does not stultify the divine nature by imposing on divinity responsibility for being able to relieve human suffering while refusing to do so. The sufferings of life are the sufferings of the divine spirit in search of progress in the objective world.[142]

New religions

There are many new religious movements in East Asia, and some with millions of followers: Chondogyo, Tenrikyo, Cao Đài, and Seicho-No-Ie. New religions typically have unique explanations for the meaning of life. For example, in Tenrikyo, one is expected to live a Joyous Life by participating in practices that create happiness for oneself and others.

Iranian religions

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrians believe in a universe created by a transcendental God, Ahura Mazda, to whom all worship is ultimately directed. Ahura Mazda's creation is asha, truth and order, and it is in conflict with its antithesis, druj, falsehood and disorder. (See also Zoroastrian eschatology).

Since humanity possesses free will, people must be responsible for their moral choices. By using free will, people must take an active role in the universal conflict, with good thoughts, good words and good deeds to ensure happiness and to keep chaos at bay.

Popular views

"What is the meaning of life?" is a question many people ask themselves at some point during their lives, most in the context "What is the purpose of life?".[10] Some popular answers include:

To realize one's potential and ideals

- To chase dreams.[143]

- To live one's dreams.[144]

- To spend it for something that will outlast it.[145]

- To matter: to count, to stand for something, to have made some difference that you lived at all.[145]

- To expand one's potential in life.[144]

- To become the person you've always wanted to be.[146]

- To become the best version of yourself.[147]

- To seek happiness[148][149] and flourish.[3]

- To be a true authentic human being.[150]

- To be able to put the whole of oneself into one's feelings, one's work, one's beliefs.[145]

- To follow or submit to our destiny.[151][152][153]

- To achieve eudaimonia,[154] a flourishing of human spirit.

To achieve biological perfection

To seek wisdom and knowledge

- To expand one's perception of the world.[144]

- To follow the clues and walk out the exit.[164]

- To learn as many things as possible in life.[165]

To know as much as possible about as many things as possible.[166] - To seek wisdom and knowledge and to tame the mind, as to avoid suffering caused by ignorance and find happiness.[167]

- To face our fears and accept the lessons life offers us.[151]

- To find the meaning or purpose of life.[168][169]

- To find a reason to live.[170]

- To resolve the imbalance of the mind by understanding the nature of reality.[171]

To do good, to do the right thing

- To leave the world as a better place than you found it.[143]

To do your best to leave every situation better than you found it.[143] - To benefit others.[6]

- To give more than you take.[143]

- To end suffering.[172][173][174]

- To create equality.[175][176][177]

- To challenge oppression.[178]

- To distribute wealth.[179][180]

- To be generous.[181][182]

- To contribute to the well-being and spirit of others.[183][184]

- To help others,[3][182] to help one another.[185]

To take every chance to help another while on your journey here.[143] - To be creative and innovative.[183]

- To forgive.[143]

To accept and forgive human flaws.[186][187] - To be emotionally sincere.[145]

- To be responsible.[145]

- To be honorable.[145]

- To seek peace.[145]

Meanings relating to religion

- To reach the highest heaven and be at the heart of the Divine.[188]

- To have a pure soul and experience God.[145]

- To understand the mystery of God.[151]

- To know or attain union with God.[189][190]

- To know oneself, know others, and know the will of heaven.[191]

- To love something bigger, greater, and beyond ourselves, something we did not create or have the power to create, something intangible and made holy by our very belief in it.[143]

- To love God[189] and all of his creations.[192]

- To glorify God by enjoying him forever.[193]

- To spread your religion and share it with others.[194] (Matthew 28:18-20)

- To act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God.[195]

- To be fruitful and multiply.[196] (Genesis 1:28)

- To obtain freedom. (Romans 8:20-21)

- To fill the Earth and subdue it.[196] (Genesis 1:28)

- To serve humankind,[197] to prepare to meet[198] and become more like God,[199][200][201][202] to choose good over evil,[203] and have joy.[204][205]

- [He] [God] who created death and life to test you [as to] who is best in deed and He is Exalted in Might, the Forgiving. (Quran 67:2)

- To worship God and enter heaven in afterlife.[206]

To love, to feel, to enjoy the act of living

- To love more.[143]

- To love those who mean the most. Every life you touch will touch you back.[143]

- To treasure every enjoyable sensation one has.[143]

- To seek beauty in all its forms.[143]

- To have fun or enjoy life.[151][183]

- To seek pleasure[145] and avoid pain.[207]

- To be compassionate.[145]

- To be moved by the tears and pain of others, and try to help them out of love and compassion.[143]

- To love others as best we possibly can.[143]

- To eat, drink, and be merry.[208]

To have power, to be better

Life has no meaning

- Life or human existence has no real meaning or purpose because human existence occurred out of a random chance in nature, and anything that exists by chance has no intended purpose.[171]

- Life has no meaning, but as humans we try to associate a meaning or purpose so we can justify our existence.[143]

- There is no point in life, and that is exactly what makes it so special.[143]

One should not seek to know and understand the meaning of life

- The answer to the meaning of life is too profound to be known and understood.[171]

- You will never live if you are looking for the meaning of life.[143]

- The meaning of life is to forget about the search for the meaning of life.[143]

- Ultimately, a person should not ask what the meaning of their life is, but rather must recognize that it is they themselves who are asked. In a word, each person is questioned by life; and they can only answer to life by answering for their own life; to life they can only respond by being responsible.[211]

In popular culture

The mystery of life and its true meaning is an often recurring subject in popular culture, featured in entertainment media and various forms of art.

In Monty Python's The Meaning of Life, there are several allusions to the meaning of life. At the end of the film, a character played by Michael Palin is handed an envelope containing "the meaning of life", which she opens and reads out to the audience: "Well, it's nothing very special. Uh, try to be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try to live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations."[212][213][214]

Many other Monty Python sketches and songs are also existential in nature, questioning the importance we place on life ("Always Look on the Bright Side of Life") and other meaning-of-life related questioning. John Cleese also had his sit-com character Basil Fawlty contemplating the futility of his own existence in Fawlty Towers.

In Douglas Adams' popular comedy book, movie, television, and radio series The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything is given the numeric solution "42", after seven and a half million years of calculation by a giant supercomputer called Deep Thought. When this answer is met with confusion and anger from its constructors, Deep Thought explains that "I think the problem such as it was, was too broadly based. You never actually stated what the question was."[215][3][216][217][218] Deep Thought then constructs another computer—the Earth—to calculate what the Ultimate Question actually is. Later Ford and Arthur manage to extract the question as the Earth computer would have rendered it. That question turns out to be "what do you get if you multiply six by nine",[219] and it is realised that the program was ruined by the unexpected arrival of the Golgafrinchans on Earth, and so the actual Ultimate Question of Life, The Universe, And Everything remains unknown. While 6 × 9 would be written as 42 in the tridecimal numeral system, author Douglas Adams claimed that this was mere coincidence and completely serendipitous.

In The Simpsons episode "Homer the Heretic", a representation of God agrees to tell Homer what the meaning of life is, but the show's credits begin to roll just as he starts to say what it is.[220]

In Red vs. Blue season 1 episode 1 the character Simmons asks Grif the question "Why are we here?" and is a major line in the series.

In Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure, the characters are asked how we should live our lives, and reply with a version of the golden rule 'be excellent to each other' followed by 'party on, dudes!'.

In Person of Interest season 5 episode 13, an artificial intelligence referred to as The Machine tells Harold Finch that the secret of life is "Everyone dies alone. But if you mean something to someone, if you help someone, or love someone. If even a single person remembers you then maybe you never really die at all." This phrase is then repeated at the very end of the show to add emphasis to the finale.[221]

See also

- Scientific explanations

- Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life

- Sex, Death and the Meaning of Life – 2010 film

- Origin and nature of life and reality

- Abiogenesis – The natural process by which life arises from non-living matter

- Awareness – State or ability to perceive, to feel, or to be conscious of events, objects, or sensory patterns

- Being – Broad concept encompassing objective and subjective features of reality and existence

- Biosemiotics – a field of semiotics and biology that studies the prelinguistic meaning-making, or production and interpretation of signs and codes

- Dao

- Existence – Ability of an entity to interact with physical or mental reality

- Human condition – Ultimate concerns of human existence

- Logos – Term in Western philosophy, psychology, rhetoric, and religion

- Metaphysical naturalism

- Perception – Organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the environment

- Reality – Sum or aggregate of all that is real or existent

- Simulated reality

- Theory of everything – Hypothetical single, all-encompassing, coherent theoretical framework of physics

- Teleology – Philosophical study of nature by attempting to describe things in terms of their apparent purpose, directive principle, or goal

- Ultimate fate of the universe – Range of cosmological hypotheses and scenarios describing the eventual fate of the universe as we know it

- Value of life

- Culture of life

- Bioethics

- Meaningful life

- Quality of life – Term of well-being of individuals

- Value of life

- Purpose of life

- Destiny – Predetermined course of events

- Ethical living

- Intentional living

- Life extension – Concept of extending human lifespan by improvements in medicine or biotechnology

- Man's Search for Meaning – book by Viktor Frankl

- Means to an end

- Philosophy of life – Personal philosophy, whose focus is resolving the existential questions about the human condition

- Miscellaneous

- Human extinction – The hypothetical end of the human species

- Ikigai – Japanese concept: a reason for being

- Life stance

- Meaning-making

- Perennial philosophy – 15th-century philosophical idea that views all religious traditions as sharing a single truth or origin

- Vale of tears

- World riddle

- World view

References

- Jonathan Westphal (1998). Philosophical Propositions: An Introduction to Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415170536.

- Robert Nozick (1981). Philosophical Explanations. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674664791.

- Julian Baggini (2004). What's It All About? Philosophy and the Meaning of Life. US: Granta Books. ISBN 978-1862076617.

- Ronald F. Thiemann; William Carl Placher (1998). Why Are We Here?: Everyday Questions and the Christian Life. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1563382369.

- Dennis Marcellino (1996). Why Are We Here?: The Scientific Answer to this Age-old Question (that you don't need to be a scientist to understand). Lighthouse Pub. ISBN 978-0945272106.

- Hsuan Hua (2003). Words of Wisdom: Beginning Buddhism. Dharma Realm Buddhist Association. ISBN 978-0881393026.

- Paul Davies (2000). The Fifth Miracle: The Search for the Origin and Meaning of Life. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684863092. Archived from the original on 16 June 2001. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- Charles Christiansen; Carolyn Manville Baum; Julie Bass-Haugen (2005). Occupational Therapy: Performance, Participation, and Well-Being. SLACK Incorporated. ISBN 978-1556425301.

- Evan Harris Walker (2000). The Physics of Consciousness: The Quantum Mind and the Meaning of Life. Perseus Books. ISBN 978-0738204369.

- "Question of the Month: What Is The Meaning of Life?". Philosophy Now. Issue 59. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2007.