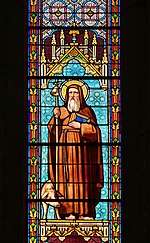

Anthony the Great

Anthony or Antony the Great (Greek: Ἀντώνιος Antṓnios; Latin: Antonius; Coptic: Ⲁⲃⲃⲁ Ⲁⲛⲧⲱⲛⲓ; c. 12 January 251 – 17 January 356), was a Christian monk from Egypt, revered since his death as a saint. He is distinguished from other saints named Anthony such as Anthony of Padua, by various epithets of his own: Saint Anthony, Anthony of Egypt, Anthony the Abbot, Anthony of the Desert, Anthony the Anchorite, and Anthony of Thebes. For his importance among the Desert Fathers and to all later Christian monasticism, he is also known as the Father of All Monks. His feast day is celebrated on 17 January among the Orthodox and Catholic churches and on Tobi 22 in the Coptic calendar.

Saint Anthony the Great | |

|---|---|

.jpg) San Antonio Abad, portrait by Francisco de Zurbarán in 1664 | |

| Venerable and God-bearing Father of Monasticism Father of All Monks | |

| Born | 12 January 251 (reputedly) Herakleopolis Magna, Egypt |

| Died | 17 January 356 (aged 105) Mount Colzim, Egypt |

| Venerated in | Coptic Orthodox Church Assyrian Church of the East Eastern Orthodox Church Oriental Orthodox Churches Catholic Church Anglican Communion |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Major shrine | Monastery of St. Anthony, Egypt Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye, France |

| Feast | 17 January (Catholic Church) 17 January (Eastern Orthodoxy) 22 Tobi (Coptic Calendar) |

| Attributes | bell; pig; book; Tau Cross[1][2] Tau cross with bell pendant[3] |

| Patronage | Animals, skin diseases, farmers, butchers, basket makers, brushmakers, gravediggers,[4] Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy, Rome[5] |

The biography of Anthony's life by Athanasius of Alexandria helped to spread the concept of Christian monasticism, particularly in Western Europe via its Latin translations. He is often erroneously considered the first Christian monk, but as his biography and other sources make clear, there were many ascetics before him. Anthony was, however, among the first known to go into the wilderness (about AD 270), which seems to have contributed to his renown.[6] Accounts of Anthony enduring supernatural temptation during his sojourn in the Eastern Desert of Egypt inspired the often-repeated subject of the temptation of St. Anthony in Western art and literature.

Anthony is appealed to against infectious diseases, particularly skin diseases. In the past, many such afflictions, including ergotism, erysipelas, and shingles, were referred to as St. Anthony's fire.

Life of Anthony

Most of what is known about Anthony comes from the Life of Anthony. Written in Greek around 360 by Athanasius of Alexandria, it depicts Anthony as an illiterate and holy man who through his existence in a primordial landscape has an absolute connection to the divine truth, which always is in harmony with that of Athanasius as the biographer.[6]

A continuation of the genre of secular Greek biography,[7] it became his most widely read work.[8] Sometime before 374 it was translated into Latin by Evagrius of Antioch. The Latin translation helped the Life become one of the best known works of literature in the Christian world, a status it would hold through the Middle Ages.[9]

Translated into several languages, it became something of a best seller in its day and played an important role in the spreading of the ascetic ideal in Eastern and Western Christianity. It later served as an inspiration to Christian monastics in both the East and the West,[10] and helped to spread the concept of Christian monasticism, particularly in Western Europe via its Latin translations.

Many stories are also told about Anthony in various collections of sayings of the Desert Fathers.

Anthony probably spoke only his native language, Coptic, but his sayings were spread in a Greek translation. He himself dictated letters in Coptic, seven of which are extant.[11]

Life

Early years

Anthony was born in Coma in Lower Egypt to wealthy landowner parents. When he was about 20 years old, his parents died and left him with the care of his unmarried sister. Shortly thereafter, he decided to follow the gospel exhortation in Matthew 19: 21, "If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasures in heaven." Anthony gave away some of his family's lands to his neighbors, sold the remaining property, and donated the funds to the poor.[12] He then left to live an ascetic life,[12] placing his sister with a group of Christian virgins.[13]

Hermit

For the next fifteen years, Anthony remained in the area,[14] spending the first years as the disciple of another local hermit.[4] There are various legends that he worked as a swineherd during this period.[15]

Anthony is sometimes considered the first monk,[14] and the first to initiate solitary desertification,[16] but there were others before him. There were already ascetic hermits (the Therapeutae), and loosely organized cenobitic communities were described by the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria in the 1st century AD as long established in the harsh environment of Lake Mareotis and in other less accessible regions. Philo opined that "this class of persons may be met with in many places, for both Greece and barbarian countries want to enjoy whatever is perfectly good."[17] Christian ascetics such as Thecla had likewise retreated to isolated locations at the outskirts of cities. Anthony is notable for having decided to surpass this tradition and headed out into the desert proper. He left for the alkaline Nitrian Desert (later the location of the noted monasteries of Nitria, Kellia, and Scetis) on the edge of the Western Desert about 95 km (59 mi) west of Alexandria. He remained there for 13 years.[4]

Anthony maintained a very strict ascetic diet. He ate only bread, salt and water and never meat or wine.[18] He ate at most only once a day and sometimes fasted through two or four days.[19][20]

According to Athanasius, the devil fought Anthony by afflicting him with boredom, laziness, and the phantoms of women, which he overcame by the power of prayer, providing a theme for Christian art. After that, he moved to one of the tombs near his native village. There it was that the Life records those strange conflicts with demons in the shape of wild beasts, who inflicted blows upon him, and sometimes left him nearly dead.[21]

After fifteen years of this life, at the age of thirty-five, Anthony determined to withdraw from the habitations of men and retire in absolute solitude. He went into the desert to a mountain by the Nile called Pispir (now Der-el-Memun), opposite Arsinoë.[14] There he lived strictly enclosed in an old abandoned Roman fort for some 20 years.[4] Food was thrown to him over the wall. He was at times visited by pilgrims, whom he refused to see; but gradually a number of would-be disciples established themselves in caves and in huts around the mountain. Thus a colony of ascetics was formed, who begged Anthony to come forth and be their guide in the spiritual life. Eventually, he yielded to their importunities and, about the year 305, emerged from his retreat. To the surprise of all, he appeared to be not emaciated, but healthy in mind and body.[21]

For five or six years he devoted himself to the instruction and organization of the great body of monks that had grown up around him; but then he once again withdrew into the inner desert that lay between the Nile and the Red Sea, near the shore of which he fixed his abode on a mountain where still stands the monastery that bears his name, Der Mar Antonios. Here he spent the last forty-five years of his life, in a seclusion, not so strict as Pispir, for he freely saw those who came to visit him, and he used to cross the desert to Pispir with considerable frequency. Amid the Diocletian Persecutions, around 311 Anthony went to Alexandria and was conspicuous visiting those who were imprisoned.[21]

Father of Monks

_-_Vier_verhalen_van_Antonius_van_Egypte_(1340)_-_Bologna_Pinacoteca_Nazionale_-_26-04-2012_9-22-59.jpg)

Anthony was not the first ascetic or hermit, but he may properly be called the "Father of Monasticism" in Christianity,[12][22][23] as he organized his disciples into a community and later, following the spread of Athanasius's hagiography, was the inspiration for similar communities throughout Egypt and, elsewhere. Macarius the Great was a disciple of Anthony. Visitors traveled great distances to see the celebrated holy man. Anthony is said to have spoken to those of a spiritual disposition, leaving the task of addressing the more worldly visitors to Macarius. Macarius later founded a monastic community in the Scetic desert.[24]

The fame of Anthony spread and reached Emperor Constantine, who wrote to him requesting his prayers. The brethren were pleased with the Emperor's letter, but Anthony was not overawed and wrote back exhorting the Emperor and his sons not to esteem this world but remember the next.[11]

The stories of the meeting of Anthony and Paul of Thebes, the raven who brought them bread, Anthony being sent to fetch the cloak given him by "Athanasius the bishop" to bury Paul's body in, and Paul's death before he returned, are among the familiar legends of the Life. However, belief in the existence of Paul seems to have existed quite independently of the Life.[25]

In 338, he left the desert temporarily to visit Alexandria to help refute the teachings of Arius.[4]

Final days

When Anthony sensed his death approaching, he commanded his disciples to give his staff to Macarius of Egypt, and to give one sheepskin cloak to Athanasius of Alexandria and the other sheepskin cloak to Serapion of Thmuis, his disciple.[26] Anthony was interred, according to his instructions, in a grave next to his cell.[11]

Temptation

Accounts of Anthony enduring supernatural temptation during his sojourn in the Eastern Desert of Egypt inspired the often-repeated subject of the temptation of St. Anthony in Western art and literature.[27]

Anthony is said to have faced a series of supernatural temptations during his pilgrimage to the desert. The first to report on the temptation was his contemporary Athanasius of Alexandria. It is possible these events, like the paintings, are full of rich metaphor or in the case of the animals of the desert, perhaps a vision or dream. Emphasis on these stories, however, did not really begin until the Middle Ages when the psychology of the individual became of greater interest.[4]

Some of the stories included in Anthony's biography are perpetuated now mostly in paintings, where they give an opportunity for artists to depict their more lurid or bizarre interpretations. Many artists, including Martin Schongauer, Hieronymus Bosch, Dorothea Tanning, Max Ernst, Leonora Carrington and Salvador Dalí, have depicted these incidents from the life of Anthony; in prose, the tale was retold and embellished by Gustave Flaubert in The Temptation of Saint Anthony.[28]

The satyr and the centaur

Anthony was on a journey in the desert to find Paul of Thebes, who according to his dream was a better Hermit than he.[29] Anthony had been under the impression that he was the first person to ever dwell in the desert; however, due to the dream, Anthony was called into the desert to find his "better", Paul. On his way there, he ran into two creatures in the forms of a centaur and a satyr. Although chroniclers sometimes postulated they might have been living beings, Western theology considers to have been demons.[29]

While traveling through the desert, Anthony first found the centaur, a "creature of mingled shape, half horse half-man," whom he asked about directions. The creature tried to speak in an unintelligible language, but ultimately pointed with his hand the way desired, and then ran away and vanished from sight.[29] It was interpreted as a demon trying to terrify him, or alternately a creature engendered by the desert.[30]

Anthony found next the satyr, a "a manikin with hooked snout, horned forehead, and extremities like goats's feet." This creature was peaceful and offered him fruits, and when Anthony asked who he was, the satyr replied, "I'm a mortal being and one of those inhabitants of the desert whom the Gentiles deluded by various forms of error worship under the names of Fauns, Satyrs, and Incubi. I am sent to represent my tribe. We pray you in our behalf to entreat the favor of your Lord and ours, who, we have learnt, came once to save the world, and 'whose sound has gone forth into all the earth.'" Upon hearing this, Anthony was overjoyed and rejoiced over the glory of Christ. He condemned the city of Alexandria for worshipping monsters instead of God while beasts like the satyr spoke about Christ.[29]

Silver and gold

Another time Anthony was travelling in the desert and found a plate of silver coins in his path.[31]

Demons in the cave

Once, Anthony tried hiding in a cave to escape the demons that plagued him. There were so many little demons in the cave though that Anthony's servant had to carry him out because they had beaten him to death. When the hermits were gathered to Anthony's corpse to mourn his death, Anthony was revived. He demanded that his servants take him back to that cave where the demons had beaten him. When he got there he called out to the demons, and they came back as wild beasts to rip him to shreds. All of a sudden a bright light flashed, and the demons ran away. Anthony knew that the light must have come from God, and he asked God where he was before when the demons attacked him. God replied, "I was here but I would see and abide to see thy battle, and because thou hast mainly fought and well maintained thy battle, I shall make thy name to be spread through all the world."[32]

Veneration

Anthony had been secretly buried on the mountain-top where he had chosen to live. His remains were reportedly discovered in 361, and transferred to Alexandria. Some time later, they were taken from Alexandria to Constantinople, so that they might escape the destruction being perpetrated by invading Saracens. In the eleventh century, the Byzantine emperor gave them to the French Count Jocelin. Jocelin had them transferred to La-Motte-Saint-Didier, later renamed.[4] There, Jocelin undertook to build a church to house the remains, but died before the church was even started. The building was finally erected in 1297 and became a centre of veneration and pilgrimage, known as Saint-Antoine-l'Abbaye.

Anthony is credited with assisting in a number of miraculous healings, primarily from ergotism, which became known as "St. Anthony's Fire". He was credited by two local noblemen of assisting them in recovery from the disease. They then founded the Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony in honor of him, who specialized in nursing the victims of skin diseases.[4]

Veneration of Anthony in the East is more restrained. There are comparatively few icons and paintings of him. He is, however, regarded as the "first master of the desert and the pinnacle of holy monks", and there are monastic communities of the Maronite, Chaldean, and Orthodox churches which state that they follow his monastic rule.[4] During the Middle Ages, Anthony, along with Quirinus of Neuss, Cornelius and Hubertus, was venerated as one of the Four Holy Marshals (Vier Marschälle Gottes) in the Rhineland.[33]

Legacy

Though Anthony himself did not organize or create a monastery, a community grew around him based on his example of living an ascetic and isolated life. Athanasius' biography helped propagate Anthony's ideals. Athanasius writes, "For monks, the life of Anthony is a sufficient example of asceticism."[4]

Coptic literature

Examples of purely Coptic literature are the works of Anthony and Pachomius, who only spoke Coptic, and the sermons and preachings of Shenouda the Archmandrite, who chose to only write in Coptic. The earliest original writings in Coptic language were the letters by Anthony. During the 3rd and 4th centuries many ecclesiastics and monks wrote in Coptic.[34]

In popular literature

The main character in the Hervey Allen novel Anthony Adverse, and the 1936 film of the same name, is an abandoned child who is placed in a foundling wheel on the saint's feast day, and given the name Anthony in his honor.

See also

- Coptic Saints

- Chariton the Confessor (mid-3rd century-c. 350), contemporary monk in the Judaean desert

- Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers, early Christian hermits, ascetics, and monks who lived mainly in the Scetes desert of Egypt beginning around the third century AD

- Hilarion (291–371), anchorite and saint considered by some to be the founder of Palestinian monasticism

- Monastery of Saint Anthony, Egypt

- Pachomius the Great (c. 292–348), Egyptian saint generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism

- Patron saints of ailments, illness and dangers

- Paul of Thebes (c. 226/7-c. 341), known as "Paul, the First Hermit", who preceded both Anthony and Chariton

- St. Anthony Hall, American fraternity and literary society

- Saint Anthony the Great, patron saint archive

Notes

- Jack Tresidder, ed. (2005). The Complete Dictionary of Symbols. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-4767-5.

- Cornwell, Hilarie; James Cornwell (2009). Saints, Signs, and Symbols (3rd ed.). Harrisburg: Morehouse Publishing. ISBN 0-8192-2345-X.

- Liechtenstein, the Princely Collections, catalogue of Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, p.276

- Michael Walsh, ed. (1991). Butler's Lives of the Saints (Concise, Revised & Updated, 1st HarperCollins ed.). San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0-06-069299-5.

- "Pontificia Accademia Ecclesiastica, Cenni storici (1701–2001)". Pontificia Accademia Ecclesiastica (in Italian). Vatican, Roman Curia. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Endsjø, Dag Øistein (2008). Primordial landscapes, Incorruptible Bodies. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 1-4331-0181-5.

- Hägg, Tomas. "The Life of St Antony between Biography and Hagiography", Ashgate Research Companion to Byzantine Hagiography. Vol. I, Farnham; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011 ISBN 9780754650331

- "Athanasius of Alexandria: Vita S. Antoni [Life of St. Antony] (written bwtween 356 and 362)". Fordham University. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- The Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism, Bernhart McGinn ISBN 0-8129-7421-2

- "Athanasius". Christian History | Learn the History of Christianity & the Church. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Saint Anthony of Egypt", Lives of the Saints, John J. Crawley & Co., Inc.

- EB (1878).

- Athanasius (1998). Life of Antony. 3. Carolinne White, trans. London: Penguin Books. p. 10. ISBN 0-8146-2377-8.

- EB (1911).

- Sax, Boria. "How Saint Anthony Brought Fire to the World". Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- "A few words about the life and writings of St. Anthony the Great". orthodoxthought.sovietpedia.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Philo. De Vita Contemplativa [English: The Contemplative Life]..

- Watterson, Barbara. (1989). Coptic Egypt. Scottish Academic Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0707305561 "His food consisted of bread, salt and water: meat and wine he never touched at all. He slept upon a mat, and sometimes upon the bare ground; and never washed or cleansed his body with oil and strigil."

- Smedley, Edward; Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John. (1845). Encyclopaedia Metropolitana. Volume 20. London. p. 228. "He never tasted food till sunset, and sometimes fasted through two or even four days; his diet was of the simplest kind, bread, salt and water, his bed was straw, or frequently bare ground."

- Harmless, William. (2004). Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism. Oxford University Press. pp. 61-62. ISBN 0-19-516222-6

- Butler, Edward Cuthbert. "St. Anthony." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 19 May 2019

- "Britannica, Saint Anthony".

- "Saint Anthony Father of the Monks". coptic.net.

- Healy, Patrick. "Macarius." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 16 (Index). New York: The Encyclopedia Press, 1914. 19 May 2019

- Bacchus, Francis Joseph. "St. Paul the Hermit." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 19 May 2019

- Cross, F. L., ed. (1957) The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford U. P., p. 1242

- Alan Shestack; Fifteenth century Engravings of Northern Europe; no.37, 1967, National Gallery of Art, Washington(Catalogue), LOC 67-29080

- Leclerc, Yvan. "Gustave Flaubert - études critiques - Le saint-poème selon Flaubert : le délire des sens dans La Tentation de saint Antoine". flaubert.univ-rouen.fr. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Vitae Patrum, Book 1a- Collected from Jerome. Ch. VI

- Bacchus, Francis. "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Saint Paul the Hermit". Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- "Venerable and God-bearing Father Anthony the Great". oca.org. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "The Golden Legend: The Life of Anthony of Egypt". Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- "Quirinus von Rom" [English: Quirinus of Rome] (in German). Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- "Coptic Literature". Retrieved 4 January 2013.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 96–97

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anthony the Great. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anthony the Great |

- "Spiritual Considerations on the Life of Saint Antony the Great" is a manuscript, from 1864, in Arabic, that is a translation of a Latin work about the life of Saint Anthony

- "Saint Anthony Abbot" at the Christian Iconography website

- "Of the Life of Saint Anthony" from Caxton's translation of the Golden Legend

- Colonnade Statue in St Peter's Square