Germanic paganism

Germanic paganism refers to the ethnic religion practiced by the Germanic peoples from the Iron Age until Christianisation during the Middle Ages. It was an essential element of early Germanic culture. From both archaeological remains and literary sources, it is possible to trace a number of common or closely related beliefs amid the Germanic peoples into the Middle Ages, when the last areas in Scandinavia were Christianized. Rooted in Proto-Indo-European religion, Proto-Germanic religion expanded during the Migration Period, yielding extensions such as Old Norse religion among the North Germanic peoples, the paganism practiced amid the continental Germanic peoples, and Anglo-Saxon paganism among the Old English-speaking peoples. Germanic religion is best documented in several texts from the 10th and 11th centuries, where they have been best preserved in Scandinavia and Iceland.

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe

Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians

East Asia Europe East Asia Europe

Indo-Aryan Iranian

|

|

Religion and mythology

Indo-Aryan Iranian Others Europe

|

|

Geographical dispersion

Germania was the Roman term for the area east of the Rhine and north of the Danube and up to the islands of the Baltic Sea[1] (its namesake originates from Julius Caesar, who used it in his treatise on the Gallic Wars, Commentarii de Bello Gallico). The Germanic core area, Magna Germania, was located in ancient Europe in the northern European lowland, which mainly includes present-day Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, and the Scandinavian peninsula.[2] However, the boundaries of Germania were not clearly defined, as large Germanic populations lived within the borders of the Roman Empire, and the Roman influence reached far into "free Germania" across the border of Limes.[3] In Central Europe, the Celtic culture was already dominant and early Germanic religious practices were influenced by the Celts. Later, elements from the Roman culture were mixed into the Germanic culture, which includes archaeological evidence of Roman gods, statues, and gold mining. Germanic people have never really constituted a uniform group with a common or ubiquitous culture, but some general core beliefs system are known from medieval texts, which may be the result of a fusion of various beliefs across the expanse of Germanic tribes throughout central Europe. Among the East Germanic peoples, traces of Gothic paganism may be discerned from scant artifacts and attestations. According to historian John Thor Ewing, as a religion, the Germanic version consisted of "individual worshippers, family traditions and regional cults within a broadly consistent framework".[4]

Sources

Few written sources for Germanic paganism exist, and few of those that do were written by participants in that religion. Traditional oral literature associated with the pre-Christian religion was most likely deliberately suppressed as Christian institutions became dominant in Germany, England, and Scandinavia during the Middle Ages.[5] Descriptions of early Germanic religious practices are, however, found in the works of Roman writers such as Tacitus in his first-century work Germania.[6]

Only in medieval Iceland was a large amount of Germanic-language material written on the subject of pagan traditions, principally the mythological poems of the Poetic Edda, Prose Edda, and skaldic verse.[7] These works have enormous significance for our understanding of the ancient religious traditions. However, these sources were recorded after Christianity became dominant in Iceland by writers who themselves were Christians.[8] Some traces of Germanic religion are preserved in other works by medieval Christians like the Middle High German Nibelungenlied and the Old English Beowulf.[9]

Medieval and post-medieval folklore has also been used as a source for older beliefs. But this too was influenced by Christianity and changed in shape.[10]

However, whereas stories can travel quickly and easily change over time, making late texts unreliable evidence for early Germanic culture, language changes in somewhat more predictable ways. Through the comparative method, it is possible to compare words in related languages and rationally reconstruct what their lost, earlier forms must have been, and to some extent what those earlier forms must have meant. This in turn allows the reconstruction of the names of some gods, supernatural beings, and ritual practices. For example, all the Germanic languages use a similar neuter noun to denote pagan gods: Gothic guþ, Old English god, Old High German got, and Old Norse guð. Proto-Germanic, therefore, surely had a similar word with a similar sense.[11]

History

Proto-Germanic Pagan Religion

Little is known for certain about the roots of Germanic religion.[12]

Roman Iron Age

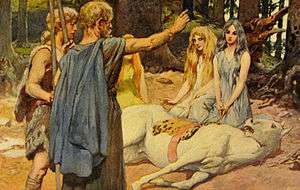

Early forms of Germanic religion are known exclusively from archaeological remains and can therefore only be interpreted on the basis of comparative studies with other religions or through the evaluation of Scandinavian literature, who, as the last converts among the practitioners of Germanic religion, maintained a written account of their religion into the Middle Ages.[13] In addition to the rich archaeological finds, like the evidence of a widespread veneration of a fire god,[14] there is also linguistic evidence attesting to Germanic religious practices. Description of the oldest forms of the Germanic religion are based on uncertain reconstructions, which in turn are based on comparisons with other material.[lower-alpha 1] Archaeological findings suggest that the Germanic peoples practiced some of the same 'spiritual' rituals as the Celts, including sacrifice, divination, and the belief in a spiritual connection with the natural environment around them.[15] Germanic priestesses were feared by the Romans, as these tall women with glaring eyes, wearing flowing white gowns often wielded a knife for sacrificial offerings. Captives might have their throats cut and be bled into giant cauldrons or have their intestines opened up and the entrails thrown to the ground for prophetic readings.[16][lower-alpha 2] Spiritual rituals frequently occurred in consecrated groves or upon islands on lakes where perpetual fires burned.[18]

Various deities found in Germanic paganism occur widely among the Germanic peoples, most notably the god known to the continental Germanic peoples as Wodan or Wotan, to the Anglo-Saxons as Woden, and to the Norse as Óðinn, as well as the god Thor—known to the continental Germanic peoples as Donar, to the Anglo-Saxons as Þunor and to the Norse as Þórr. Christianity had no relevance for the pre-Christian Germanic peoples until their contact and integration with Rome.[19]

Julius Caesar

One of the oldest written sources on Germanic religion is Julius Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico, where he compares the very intricate Celtic customs with the perceived very "primitive" Germanic traditions:

The German way of life is very different. They have no druids to preside over matter related to the divine, and they do not have much enthusiasm for sacrifices. They count as gods only those phenomenon that they can perceive and by whose power they are plainly helped, the Sun, Fire, and Moon; others they do not know even from hearsay. Their whole life is spent on hunting and military pursuits. (Caesar, Gallic War 6.21.1–6.21.3)[20]

Caesar's descriptions of the religion of the Germanic tribes differ greatly from what other sources show, and so it is not given high source value by modern religious researchers. In general, he describes Germania as a barbaric wonderland, very different from the Italy from which he comes. Many of the characteristics he attributes to the population are thus in contrast to the Romans. An interesting detail, however, is his identification of the most important deity in Gaul being the same as the Roman Mercury; he likewise references other Roman gods being found in Germanic beliefs.

Among the gods, Mercury has the most important cult; his sacred images are very frequent. The Gauls call him the inventor of every art and skill, the guide on roadways and journeys, and they believe he has the greatest power over trade and the pursuit of profit. After him, they venerate Apollo, Mars, Jupiter, and Minerva. Of these, they think in much the same way as other peoples do, holding that Apollo dispels disease, Minerva passes along the foundations of arts and crafts, Jupiter rules the heavenly gods, and Mars governs war. (Caesar, Gallic War 6.17.1)[21]

Tacitus

A later and much more detailed description of the Germanic religion was written by Tacitus around 100 AD. His ethnographic descriptions in Germania remain highly valued. According to this, the Germanic peoples sacrificed both animals and humans to their gods, which he identified with Hercules and Mars.[22] He also tells that the largest group, the Suebi, also sacrificed Roman prisoners of war to a goddess whom he identified with Isis.[22]

Another deity, whom he calls Nerthus, is cultivated as a goddess by a number of groups in the northwestern region. According to Tacitus's account, her followers believed that Nerthus interacted directly in human affairs.[23] Her main shrine was in the grove of Castum, located on an island. A covered wagon pulled by bulls was devoted to the goddess and only the high priest was permitted to touch it. This pastor was able to see the goddess stepping into the cart. It was carried all over the country and wherever it arrived, a party and feast in her honor was held. The priest proclaimed festivities over when the goddess was tired of contact with mortals, then the wagon and curtain were washed. The slave performing the purification ritual was subsequently thrown into the lake. During the time the goddess traveled, these tribes did not go to war and did not touch any weapons.[23] According to Tacitus, the Germans perceived temple buildings as inappropriate homes for the gods, nor did they depict them in human form, in the same way that the Romans did. Instead, they cultivated them in sacred forests or groves.[24]

Tacitus' reliability as a source can be characterized by his rhetorical tendencies, since one of the purposes of Germania was to present his own compatriots with an example of the virtues he believed they were missing.[25]

Germanic Iron Age

Paganism was still being practiced by the Germanic peoples when the Roman emperor Constantine the Great died in 337 AD, despite his conversion to Christianity; Constantine did not, however, ban pagan rituals at select religious temples across the Empire.[26] Sometime between 391–392, Theodosius I made an official proclamation which outlawed pagan religious practices throughout his region of influence with various successors like Justinian I doing likewise.[26] The Franks were converted directly from paganism to Christianity under the leadership of Clovis I in about 496 without an intervening time as Arian Christians. Eventually the Gothic tribes turned away from their Arian faith and in 589 converted to trinitarian Christianity.[27]

Pagan beliefs amid the Germanic peoples were reported by some of the earlier Roman historians and in the 6th century AD another instance of this appears when the Byzantine historian and poet, Agathias, remarked that the Alemannic religion was "solidly and unsophisticatedly pagan."[28] However, during the Germanic Iron Age, the Germanic culture was increasingly exposed to the influence of Christianity and Mediterranean culture; for example, the Gothic Christian convert Ulfilas translated the Bible from Greek into Gothic in the mid 4th century, creating the earliest known translation of the Bible into a Germanic language.[29] Another aspect of this development can be seen, for example, in Jordanes, who wrote the story of the Goths, Getica, in the 6th century, since they had been Christians for more than 150 years and dominated the ancient Roman core area, Italy. Jordanes wrote that the Goths' chief god was Mars, whom they believed had been born among them. Jordanes does not bother using the god's original name, but instead employs the Latin form (Mars) and avows the Goths sacrificed captives to him.[30] The Goths were converted to the Arian form of Christianity in the 4th century at the time when Catholicism became the dominant religion of the Roman Empire, earning them the label of heretics.[31] Over time, the ancient religious traditions were replaced by the Christian culture, first to the south, later to the north. The early transition to Christianity and the rapid disappearance of the realms meant that the religious practices of the East Germanic tribes predating Christianity are almost unknown.[32]

England

Germanic-speakers are well attested to have been stationed in the part of Roman Britain corresponding to England, and their religious practices, combining traditional and Roman elements, are evidenced in archaeology, particularly in the form of inscriptions.[33]

From the fifth century, Germanic-speaking Anglo-Saxon culture became established in England, and the later writings of its Christian writers an important source for pre-Christian Germanic religion. For example, the Christian monk Bede, who in the early eighth century reproduced a traditional, non-Christian calendar in his work De Temporum Ratione, noted that the Germanic Angles began their year on 24–25 December.[34] In addition, some pieces of Old English poetry have survived, all passed on by Christian writers. Important works include Beowulf[35][lower-alpha 3] and some Anglo-Saxon metrical charms.[37][38]

Middle Ages

When the Germanic Lombards invaded Italy in the mid-sixth century, their forces consisted of persons practicing orthodox and the Arian form of Christianity, but a significant portion of them remained wedded to their pagan religious heritage.[39] Over time, the balance between pagan and Christian believers began to change. Eventually for many continental Germanic peoples who still clung to their ancient faith, the conversion to Christianity was achieved by armed force, successfully completed by Charlemagne, in a series of campaigns (the Saxon Wars). These wars brought Saxon lands into the Frankish Empire.[40] Massacres, such as the Bloody Verdict of Verden, where as many as 4,500 people were beheaded according to one of Charlemagne's chroniclers, were a direct result of this policy.[41] Several centuries later, Anglo-Saxon and Frankish missionaries and warriors undertook the conversion of their Saxon neighbors. A key event was the felling of Thor's Oak near Fritzlar by Boniface in 723 AD. According to surviving accounts, when Thor failed to strike Boniface dead after the oak hit the ground, the Franks were amazed and began their conversion to the Christian faith.[lower-alpha 4]

During the eighth-century the Carolingian Franks sought to stamp out Germanic paganism, when for instance, Charlemagne destroyed the mighty tree trunk Irminsul that supported the heavenly vault of pagan Saxons in much the same way that Boniface had destroyed Thor's Oak before.[42] Charlemagne then instituted a forced mass-baptism, which was never forgiven and incited the Saxons to revolt whenever Frankish forces were far away; the Saxons—under the leadership of Widukind—even wiped-out Christian mission centres in Frankish territory.[43] Historian J.M. Wallace-Hadrill asserts that Charlemagne was "in deadly earnest" about extirpating paganism and that his "kingly task" included converting the heathen pagans "by fire and sword if necessary."[44] Germanic paganism's lasting power and influence is revealed to some degree by the amount of anti-pagan measures undertaken during the period of Frankish ascendancy.[44]

Transition from paganism to Christianity was nonetheless an uneven process. For example, when the formidable Harald Gormsson attempted to impose Christianity on Denmark in the mid-10th century, the inhabitants resented the change, which led to his son driving him out of the country and returning it to its pagan practices.[45] Sometime around 1000 CE, Iceland was formally declared Christian, however, pagan religious practices were tolerated in the private sphere. The change of religion took place in some places peacefully, while in others through forced conversion. Norwegian King, Olaf II, (later canonized as St Olaf) who reigned in the early 11th century, attempted to spread Christianity throughout his kingdom, but was forced into exile by a rebellion in 1028 and killed at the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030. In 1080, Sweden's King Inge the Elder, who had converted to Christianity, was exiled from Uppsala by his own people when he refused to sacrifice to the pagan gods.[46] Nonetheless, most of Scandinavia turned from their Nordic pagan practices and converted to Christianity by the 11th century.[47][48] Adam of Bremen provided the last description of widespread paganism being practiced in the Nordic countries.[49]

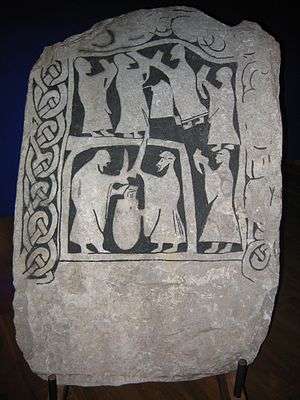

Viking era

_vit_bakgr.jpg)

The Scandinavian religion in the early Middle Ages is far better documented than the former Germanic religions, thanks especially to the texts written down in Iceland between 1150 and 1400.[50] Bronze Age personal ornaments show images of their gods on chariots, and rock carvings all across Scandinavia south of Trondheim-Swedish Uppland reveal gods, priests, and various fauna.[51] Sacrifice was known to be merely a part of festivals where the various gods received gifts, or whenever one tried to predict and influence the events of the coming year. The relationship between gods and humans was understood as one that resembled the connection between a great man and those submissive to him; therefore it was important to routinely confirm the relationship with the gods through gifts. Blood sacrifices were used in times of crisis and for the holidays.[52] Ninth-century accounts of the Viking Rus' of Novgorod (perhaps the furthest East that Germanic religious practices manifest) include the sacrifice of "men, women, and cattle" to their deities.[53]

While Christian conversion happened first in Denmark and then Norway, thanks largely to Harald Bluetooth, the Swedish royal household was the last to accept Christian baptism.[54] Pagan religion formed the core of Nordic religious identity and their bond was as much their non-Christian identity and their related tongue than it was their common worship of Odinn, Thor, or Frey.[55] Even after conversion, there are reports that Norsemen like Helgi the Lean—who was a professed Christian—made vows to Thor during sea-voyages or when matters of utmost importance arose, demonstrating how some were slow to give up their old gods entirely.[56]

Influences

Celtic Iron Age

During the transition between the Bronze Age and the Iron Age (about 500 BC), there was a shift in both living and religious customs.[57] The archaeological finds show a society that was changed, instead of burying their dead, they were now starting to burn them before ceremoniously placing them in the ground.[57] This burial practice remained dominant right up to the transition to Christianity in the Middle Ages. In later sources, it appears that the Germanic peoples believed that the dead would continue to live in a celestial kingdom through burning, while those who were laid in the earth without being burned would remain down there.[58] Among finds that probably had religious significance, objects of Celtic origin dominate, and the mythological motifs found in many cases have clear connections to the Mediterranean region or Celtic culture. Based on archaeological evidence alone, it is nearly impossible to distinguish early Germans from Celts according to historian Malcolm Todd.[59] While there is limited information available on Germanic mythology in the early part of the Iron Age, the remnants that do exist indicate that there were shifts in the religious beliefs of the Germanic peoples over the centuries.[60]

Traces of Roman religion

Until about 400 AD, the borders of the Roman Empire were only about 300 km away from Scandinavia, and even closer to other German-speaking tribes. The Roman Empire was the dominant power of that time, both politically, economically and culturally in this part of the world. As the Roman Empire grew and made contact with different cultures across a vast area of Europe, local traditions eventually began borrowing cultural elements derived from the Romans; this also applies to the Germanic peoples. A telling example is that by 300 AD, the Germanic peoples began dividing the week into seven days, each day named after a particular deity.[61]

More examples include sculptures that create an overall common tradition throughout Europe, the Near-North and North Africa. In northern Europe, smaller sculptures with clear similarities to Roman models from archaeological excavations—in particular, at Funen and Øland—dating between 200 and 400 AD, consist of figures that can stand on a table and are either made of metal or wood. Unfortunately, it is impossible to identify which gods these figures are meant to depict or much about the religious beliefs attached to them.[62] A special feature of the Germanic figures, however, is the lack of female figures that were otherwise popular in the Roman Empire, which indicates a deliberate opt-out. In Roman context, these types of figures were mainly used in connection with the larch cult in private homes, where they were placed on small home-altars. However, whether they have been used for the same purpose in the Nordic countries is uncertain. Gradually, these figures disappear again from the finds, and from the Viking Age only very few and small figures are known.[63]

Sometime between 400 and 500 AD, there was an increase in the amount of gold, as indicated by archeological excavations across northern Europe—this is likely related to the extensive use of Germanic mercenaries by the Romans as they attempted to expand their empire. Round gold medals inspired by Roman coins appeared, adorned by images of Balder, Tyr and Odin. These gods were prominently worshipped by the upper class and the Germanic kings. In this example, Roman techniques were used to reproduce and convey Germanic ideas and religion.[64]

Ritual practices

Traces of Germanic pagan religion in the oldest periods during Celtic Iron Age, are known exclusively through archaeological finds. These include images and remnants of rituals, typically objects discovered in lakes and marshes, among which many of them trace back to the Neolithic Age through the Bronze Age, and most prominently continue into the Iron Age. The people of that time have probably perceived bogs and marshes as sacred places where contact with divine powers was possible. Tacitus described the home of the Germanic goddess, Nerthus, as being on an island in a lake.[23] In several bogs, raw processed wood figures have been found, generally depicting people and consisting of branches with strongly emphasized sexual features. This probably suggests that the early Germanic pagan gods of fertility were associated with water, a belief that relates to later practices.[65]

The fact that sacrifice was a fundamental element of Germanic religion can be seen in the fact that it occurs in all sorts of sources, both ancient and medieval, in place names, material relics, and in Germanic pagan mythological texts, where even the gods sacrificed.[66] Sacrifice sent objects via destruction or physical placement to places where the living no longer have access to them; most frequently this included burning them or throwing them into lakes. An important element of these rituals was the sacrificial festival, which included copious eating and drinking. Large public offerings took place in centralized locations, and in many places throughout what was once ancient Germania, the remains of such sites have been found.[67]

Wooden figures were sacrificed as were people; human victims suffered a sudden and violent death from what the archaeological finds throughout bogs—in what was once Germania—indicate. In many cases, various measures were employed to ensure that the body was held down in the bog, either using branches or stones.[68] Danish historian, Allan A. Lund, posits that the victims had been killed because they were considered witches who brought misfortune to society. He explains this by the fact that the victims had been placed in a peat bog, where they would not dissolve and thereby be transferred to the other world, but were instead, preserved forever in a border state between this and the other world.[69]

Another practice was the Germanic pagan custom of offering up weapons to their gods. In southern Scandinavia, there are about 50 sites where weapons have been thrown into a lake and sacrificed after the weapons were partially destroyed or rendered useless. At these sites, only weapons and possessions were sacrificed; no human bones are found anywhere, and only animal bones from horses can be found. Swords are bent, spears and shields are broken. The majority of this type of sacrifice comes from the period between AD 200–500 and many of them are in East Jutland in places with access to the Kattegat, a strait that is 225-km in length between Sweden and Denmark.[70] The Germans' sacrifice of defeated enemy weapons to their deities is known from ancient accounts and constitutes part of an offering to Odin, during which the weapon sacrifice affirms the connection between the worshippers and the divine.[71]

Folklore

The Germanic tribes of central Europe gradually became Christians between the 6th and 8th centuries. However, elements of the ancient mythology survived through the Middle Ages in the form of legends, adventures and epic tales and folklore. Fragments can be found, for example, in historical accounts written about the different tribes, such as Paul the Deacon's historical account of the Lombards[72] or the tales of Saint Willibrord by Alcuin, who was likewise a theologian and advisor to Charlemagne.[73]

But in relation to especially Old Norse religion and, to a lesser extent, Anglo-Saxon religion, the written sources of early spiritual practices in central Europe are of a very fragmentary nature. For example, the Merseburg charms[lower-alpha 5] is the only pre-Christian text written in Old High German and contains mentions of the deities Fulla, Wodan, and Frigg.[74] In other texts, including chronicles and historical representations, there are hints of the pagan religion, such as Charlemagne's destruction of Irminsul—reproduced in the Annales regni Francorum[75]—or the invention of the Christmas tree by Saint Boniface.[76] Other traces include the modern Scottish depiction of the "brownies".[77] As paganism was marginalized by Christianity, parts of the pre-Christian religion continued in the folklore of the rural population; Germanic mythology therefore survived in fairy tales, which the Brothers Grimm collected and published in their work.[78][lower-alpha 6]

Runes

An important Roman contribution to Germanic culture was writing. Around 200 AD, Runic inscriptions begin to appear in southern Scandinavia and did not cease until about 1300. The origin of this particular Germanic script can be linked to the strong Roman-influenced power center at Stevns in southern Denmark.[80] Researchers have long debated whether the runes had only religious significance or if they were also used for everyday writing. Today, most scholars believe that the script could not have survived so long if it was used exclusively in special ritual contexts [80] It is known for certain that runes were frequently used for religious purposes. Within the rune magic system, each rune sign had a special meaning, and the cumulative writing down of the entire alphabet series—the futhark—functioned as a magic formula. Also, in other contexts, the written text of the rune was used for spells on weapons and personal effects.[81]

Further evidence of the religious context of runes and their importance shows up in the Old Saxon epic poem, Heliand, written in Old High German verse from the ninth-century, whereby the work uses secular and pagan phrases in telling the gospel narrative. One particular line reads, gerihti us that geruni ("reveal to us the runes"), demonstrating a conflation of the Christian idea "Lord, teach us to pray" with ancient pagan practices.[82] Early proselytizers of the Christian faith had to use familiar vernacular equivalents to convey Christian concepts to their pagan brethren.[83] An enigmatic fusion of the ancient Germanic pagan, Roman, and Christian ideas shows up on the Anglo-Saxon chest known as Franks Casket, which contains a mixture of the runic and Roman alphabets.[84]

Variations of Germanic paganism

- Anglo-Saxon paganism

- Continental Germanic mythology

- Frankish mythology

- Gothic paganism

- Old Norse religion

See also

References

Informational Notes

- See the following work for more on this: D. H. Green, Language and History in the Early Germanic World (New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- The ancient rites of the Cimbri, whose priestesses carried out these practices according to the ancient biographer Strabo, show up on bowls found in Jutland.[17]

- Beowulf has also been described as the "moral gene-pool" of a bygone warrior aristocracy)[36]

- See: Levison (1905). Vitae Sancti Bonifatii archiepiscopi moguntini, pp. 31–32.

- See: F. R. Schroder, "Balder und der zweite Merseburger Spruch," Germanisch-Romanische Monatsschrift 34 (1953): 166–183

- The beginning of Germanic philology proper begins in the early 19th century, with Rasmus Rask's Icelandic Lexicon of 1814, and was in full bloom by the 1830s, with Jacob Grimm's Deutsche Mythologie giving an extensive account of reconstructed Germanic mythology and composing a German dictionary (Deutsches Wörterbuch) of Germanic etymology.[79]

Citations

- Heather 2005, pp. 49–53.

- Manco 2013, p. 207.

- Heather 2012, pp. 5–8.

- Ewing 2010, p. 9.

- Frassetto 2003, p. 180.

- Eliade 1984, pp. 143, 475fn.

- Eliade 1984, pp. 168, 470fn.

- Eliade 1984, p. 154.

- Eliade 1984, p. 170.

- Heide & Bek-Pedersen 2014, pp. 11–16.

- Green 1998, pp. 14–16.

- Shaw 2011, pp. 9–14.

- Frassetto 2003, p. 177.

- Frassetto 2003, p. 178.

- Burns 2003, p. 367.

- Williams 1998, pp. 81–82.

- Jones 1984, p. 22.

- Williams 1998, p. 82.

- Burns 2003, p. 368.

- Caesar 2017, p. 187.

- Caesar 2017, p. 186.

- Tacitus 2009, p. 42.

- Tacitus 2009, p. 58.

- Beare 1964, p. 71.

- Beare 1964, p. 72–73.

- Cameron 1997, p. 98.

- Pohl 1997, p. 37.

- Drinkwater 2007, p. 117.

- Bauer 2010, p. 44.

- Schwarcz 1999, p. 450.

- Santosuo 2004, pp. 14–16.

- James 2014, pp. 215–225.

- Shaw 2011, pp. 37–48.

- Jones & Pennick 1995, p. 124.

- Artz 1980, pp. 209–210.

- Brown 2006, p. 478.

- Vaughan-Sterling 1983, pp. 186–200.

- Jolly 1996.

- Geary 2002, p. 125.

- McKitterick 2008, pp. 103–106.

- Wilson 2005, p. 47.

- Wallace-Hadrill 2004, p. 97.

- Wallace-Hadrill 2004, pp. 97–98.

- Wallace-Hadrill 2004, p. 98.

- Jones & Pennick 1995, p. 136.

- Jones & Pennick 1995, pp. 136–137.

- Winroth 2012, pp. 138–144.

- Kendrick 2013, pp. 118–123.

- Dowden 1999, pp. 291–292.

- DuBois 1999, pp. 12, 36–37, 175.

- Jones 1984, pp. 18–19.

- Davidson 1965, pp. 110–124.

- Jones 1984, p. 255.

- Jones 1984, pp. 73–74.

- Jones 1984, p. 74.

- Jones 1984, p. 277.

- Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 146.

- Davidson 1965, p. 52.

- Todd 2004, p. 253.

- Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 325–329.

- Axboe 2005, p. 47.

- Thrane 2005, p. 37.

- Thrane 2005, pp. 37–40.

- Thrane 2005, pp. 49–51.

- Kofoed & Warming 1989, pp. 21–22.

- Persch 2005, pp. 123–124.

- Persch 2005, pp. 124–127.

- van der Sanden & Stuyts 1996, pp. 174–175.

- Lund 2002, pp. 83–85.

- Ilkjær 2000, p. 144.

- Kofoed & Warming 1989, p. 24.

- Ghosh 2015, pp. 115–117.

- Frassetto 2003, p. 21.

- Jones & Pennick 1995, p. 162.

- Scholz 1972, pp. 8–9.

- Forbes 2007, p. 45.

- Alexander 2013, p. 64.

- Letcher 2014, pp. 94–95.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 912.

- Stoklund 1994, p. 160.

- Kofoed & Warming 1989, pp. 77–81.

- Fletcher 1997, pp. 265–267.

- Fletcher 1997, p. 267.

- Fletcher 1997, pp. 268–271.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Marc (2013). Sutton Companion to British Folklore, Myths & Legends. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-5427-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Artz, Frederick B. (1980). The Mind of the Middle Ages: An Historical Survey, A.D. 200–1500. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-22602-840-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Axboe, Morten (2005). "Guld og Guder". In Torsten Capelle; Christian Fischer; Morten Axboe; Silkeborg Museum; Karen M. Boe (eds.). Ragnarok: Odins Verden [Ragnarok: Odin's World] (in Danish). Silkeborg: Silkeborg Museum Publishing. OCLC 68385544.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bauer, Susan Wise (2010). The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05975-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beare, W. (1964). "Tacitus on the Germans". Greece & Rome. Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association. 11 (1): 64–76. doi:10.1017/S0017383500012675. JSTOR 642633.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Peter (2006). The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200–1000. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-69116-177-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burns, Thomas (2003). Rome and the Barbarians, 100 B.C.—A.D. 400. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7306-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caesar, Julius (2017). "Gallic War". In Raaflaub, Kurt A. (ed.). The Landmark Julius Caesar—The Complete Works: Gallic War, Civil War, Alexandrian War, African War, and Spanish War. Translated by Kurt A. Raaflaub. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-30737-786-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cameron, Averil (1997). "Cult and Worship in East and West". In Leslie Webster; Michelle Brown (eds.). The Transformation of the Roman World, AD 400–900. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-0585-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. 22. New York: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davidson, H.R. Ellis (1965). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14013-627-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dowden, Ken (1999). European Paganism. New York; London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41512-034-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drinkwater, John F. (2007). Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929568-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- DuBois, Thomas (1999). Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-81221-714-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eliade, Mircea (1984). A History of Religious Ideas: From Gautama Buddha to the Triumph of Christianity. Vol. 2. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-20403-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ewing, Thor (2010). Gods and Worshippers in the Viking and Germanic World. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-75243-590-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fletcher, Richard (1997). The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-2763-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forbes, Bruce David (2007). Christmas: A Candid History. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520251045.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frassetto, Michael (2003). Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-263-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geary, Patrick J. (2002). The Myth of Nations: The Medieval Origins of Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-69109-054-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ghosh, Shami (2015). Writing the Barbarian Past: Studies in Early Medieval Historical Narrative. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9-00430-522-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, D.H. (1998). Language and History in the Early Germanic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 468327031.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heather, Peter (2005). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19515-954-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heather, Peter (2012). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-989226-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heide, Eldar; Bek-Pedersen, Karen (2014). "Why a New Focus on Retrospective Methods?". In Eldar Heide; Karen Bek-Pedersen (eds.). New Focus on Retrospective Methods: Resuming Methodological Discussions. Case studies from Northern Europe. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tidedeakatemia. ISBN 978-9-51411-093-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ilkjær, Jørgen (2000). Illerup Ådal, et arkæologisk tryllespejl [Illerup Ådal: An Archaeological Mirror] (in Danish). Højbjerg: Moesgård Museum. ISBN 87-87334-40-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James, Edward (2014). Europe's Barbarians, AD 200–600. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-58277-296-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jolly, Karen Louise (1996). Popular Religion in Late Saxon England: Elf-Charms in Context. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-80784-565-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Gwyn (1984). A History of the Vikings. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-2158826.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Prudence; Pennick, Nigel (1995). A History of Pagan Europe. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-76071-210-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kendrick, T.D. (2013) [1930]. A History of the Vikings. New York: Fall River Press. ISBN 978-1-43514-641-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kofoed, Aase; Warming, Morten (1989). Old var Årle: Nordens Gamle Religioner [Old was Årle: The Old Religions of the North] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Gjellerup & Gad. ISBN 87-13-03545-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Alvin A. (1997). "Symbolism and Allegory". In Robert E. Bjork; John D. Niles (eds.). A Beowulf Handbook. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-80326-150-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Letcher, Andy (2014). "Paganism and the British Folk Revival". In Donna Weston; Andy Bennett (eds.). Pop Pagans: Paganism and Popular Music. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-84465-646-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lund, Allan A. (2002). Mumificerede moselig [Mummified in the Bog] (in Danish). Copenhagen: Høst. ISBN 978-8-71429-674-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manco, Jean (2013). Ancestral Journeys: The Peopling of Europe from the First Venturers to the Vikings. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05178-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKitterick, Rosamond (2008). Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-71645-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Persch, Alexandra (2005). "På glatis med ikonografi!: Blodoffer, drikkelag og frække sange?". In Torsten Capelle; Christian Fischer; Morten Axboe; Silkeborg Museum; Karen M. Boe (eds.). Ragnarok: Odins Verden [Ragnarok: Odin's World] (in Danish). Silkeborg: Silkeborg Museum Publishing. OCLC 68385544.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pohl, Walter (1997). "The Barbarian Successor States". In Leslie Webster; Michelle Brown (eds.). The Transformation of the Roman World, AD 400–900. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-0585-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Santosuo, Antonio (2004). Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels: The Ways of Medieval Warfare. New York: MJF Books. ISBN 978-1-56731-891-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scholz, Bernard-Walter (1972). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472061860.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schwarcz, Andreas (1999). "Cult and Religion Among the Tervingi and the Visigoths and their Conversion to Christianity". In Peter Heather (ed.). The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century: A Ethnographic Perspective. Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0851157627.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaw, Philip A. (2011). Pagan Goddesses in the Early Germanic World: Eostre, Hreda and the Cult of Matrons. Translated by Anthony R. Birley. London: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 978-0-71563-797-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stoklund, Marie (1994). "Myter, runer og tolkning". In Jens Peter Schjodt (ed.). Myte og ritual i det førkristne Nordenn: et symposium [Myth and Ritual in Pre-Christian Scandinavia: A Symposium] (in Danish). Odense: Odense Universitetsforlag. ISBN 978-8-77838-053-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tacitus (2009). Agricola and Germany. Translated by Anthony R. Birley. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19953-926-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thrane, Henrik (2005). "Romerske og germanske småfigurer". In Torsten Capelle; Christian Fischer; Morten Axboe; Silkeborg Museum; Karen M. Boe (eds.). Ragnarok: Odins Verden [Ragnarok: Odin's World] (in Danish). Silkeborg: Silkeborg Museum Publishing. OCLC 68385544.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Todd, Malcolm (2004). The Early Germans. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-63119-904-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van der Sanden, Wijnand; Stuyts, Ingelise (1996). Udødeliggjorte i mosen historierne om de nordvesteuropæiske moselig [Immortalized in the Bog: Stories of the Northwest European Bogs] (in Danish). Amsterdam: Batavian Lion International. ISBN 978-9-06707-414-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vaughan-Sterling, Judith A. (1983). "The Anglo-Saxon "Metrical Charms": Poetry as Ritual". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 82 (2): 186–200. JSTOR 27709147.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0816049646.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallace-Hadrill, J. M. (2004). The Barbarian West, 400–1000. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-63120-292-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Derek (1998). Romans and Barbarians. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-19958-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Derek (2005). Charlemagne: A Biography. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-307-27480-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winroth, Anders (2012). The Conversion of Scandinavia. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30017-026-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Grimm, Jacob (2004), Teutonic Mythology, translated by Stallybrass, James S., Dover Publications

- Buchholz, Peter (1968), "Perspectives for Historical Research in Germanic Religion", History of Religions, University of Chicago Press, 8 (2): 111–138, doi:10.1086/462579

- Polomé, Edgar C.; Rowe, Elizabeth Ashman (December 27, 2019). "Germanic Religion: An Overview". Encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia of Religion. Gale. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- North, Richard (1991), Pagan words and Christian meanings, Rodopi, ISBN 978-90-5183-305-8