Hellenistic philosophy

Hellenistic philosophy is the period of Western philosophy and Middle Eastern philosophy that was developed in the Hellenistic period following Aristotle and ending with the beginning of Neoplatonism.

Pre-Hellenistic schools of thought

The Hellenistic era saw the continuation of several pre-Hellenistic era schools of thought, including:

Sophism - a category of teachers who specialized in using the tools of philosophy and rhetoric for the purpose of teaching arete (excellence, virtue) predominantly to young statesmen and nobility.

Cynicism - an ascetic sect of philosophers beginning with Antisthenes in the 4th century BC and continuing until the 5th century AD. They believed that one should live a life of virtue in agreement with Nature. This meant rejecting all conventional desires for wealth, power, health, or celebrity, and living a life free from possessions.

- Crates of Thebes (365–285 BC)

- Menippus (c. 275 BC)

- Demetrius (10–80 AD)

Cyrenaicism - a hedonist school of philosophy founded in the fourth century BC by Aristippus, who was a student of Socrates. They held that pleasure was the supreme good, especially immediate gratifications; and that people could only know their own experiences, beyond that truth was unknowable.

- Anniceris (flourished 300 BC)

- Hegesias of Cyrene (flourished 290 BC)

- Theodorus (c. 340 – c. 250 BC)

Peripatetic school - the philosophers who maintained and developed the philosophy of Aristotle. They advocated examination of the world to understand the ultimate foundation of things. The goal of life was the eudaimonia which originated from virtuous actions, which consisted in keeping the mean between the two extremes of the too much and the too little.

- Theophrastus (371–287 BC)

- Strato of Lampsacus (335–269 BC)

- Alexander of Aphrodisias (c. 200 AD)

In addition to these schools of thought, the Hellenistic era produced many new schools of thought.

Hellenistic schools of thought

Pyrrhonism

Pyrrhonism is a school of philosophical skepticism that originated with Pyrrho in the 3rd century BC, and was further advanced by Aenesidemus in the 1st century BC. Its objective is ataraxia (being mentally unperturbed), which is achieved through epoché (i.e. suspension of judgment) about non-evident matters (i.e., matters of belief).

- Pyrrho (365–275 BC)

- Timon of Phlius (320–230 BC)

- Aenesidemus (1st century BC)

- Sextus Empiricus (2nd century AD)

Epicureanism

Epicureanism was founded by Epicurus in the 3rd century BC. It viewed the universe as being ruled by chance, with no interference from gods. It regarded absence of pain as the greatest pleasure, and advocated a simple life. It was the main rival to Stoicism until both philosophies died out in the 3rd century AD.

- Epicurus (341–270 BC)

- Metrodorus (331–278 BC)

- Hermarchus (325-250 BC)

- Zeno of Sidon (1st century BC)

- Philodemus (110–40 BC)

- Lucretius (99–55 BC)

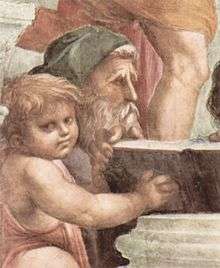

Stoicism

_-_BEIC_6353768.jpg)

Stoicism was founded by Zeno of Citium in the 3rd century BC. Based on the ethical ideas of the Cynics, it taught that the goal of life was to live in accordance with Nature. It advocated the development of self-control and fortitude as a means of overcoming destructive emotions.

- Zeno of Citium (333–263 BC)

- Cleanthes (331–232 BC)

- Chrysippus (280–207 BC)

- Panaetius (185–110 BC)

- Posidonius (135–51 BC)

- Seneca (4 BC – 65 AD)

- Epictetus (55–135 AD)

- Marcus Aurelius (121–180 AD)

Academic Skepticism

Academic skepticism is the period of ancient Platonism dating from around 266 BC, when Arcesilaus became head of the Platonic Academy, until around 90 BC, when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected skepticism, although individual philosophers, such as Favorinus and his teacher Plutarch continued to defend Academic skepticism after this date. The Academic skeptics maintained that knowledge of things is impossible. Ideas or notions are never true; nevertheless, there are degrees of truth-likeness, and hence degrees of belief, which allow one to act. The school was characterized by its attacks on the Stoics and on the Stoic dogma that convincing impressions led to true knowledge.

- Arcesilaus (316–232 BC)

- Carneades (214–129 BC)

- Cicero (106–43 BC)

Eclecticism

Eclecticism was a system of philosophy which adopted no single set of doctrines but selected from existing philosophical beliefs those doctrines that seemed most reasonable. Its most notable advocate was Cicero.

- Varro Reatinus (116–27 BC)

- Cicero (106–43 BC)

- Seneca the Younger (4 BC – 65 AD)

Hellenistic Judaism

Hellenistic Judaism was an attempt to establish the Jewish religious tradition within the culture and language of Hellenism. Its principal representative was Philo of Alexandria.

- Philo of Alexandria (30 BC – 45 AD)

- Josephus (37–100 AD)

Neopythagoreanism

Neopythagoreanism was a school of philosophy reviving Pythagorean doctrines, which was prominent in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. It was an attempt to introduce a religious element into Greek philosophy, worshipping God by living an ascetic life, ignoring bodily pleasures and all sensuous impulses, to purify the soul.

- Nigidius Figulus (98–45 BC)

- Apollonius of Tyana (15/40–100/120 AD)

- Numenius of Apamea (2nd century AD)

Hellenistic Christianity

Hellenistic Christianity was the attempt to reconcile Christianity with Greek philosophy, beginning in the late 2nd century. Drawing particularly on Platonism and the newly emerging Neoplatonism, figures such as Clement of Alexandria sought to provide Christianity with a philosophical framework.

- Clement of Alexandria (150–215 AD)

- Origen (185–254 AD)

- Augustine of Hippo (354–430 AD)

- Aelia Eudocia (401–460 AD)

Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism, or Plotinism, is a school of religious and mystical philosophy founded by Plotinus in the 3rd century AD and based on the teachings of Plato and the other Platonists. The summit of existence was the One or the Good, the source of all things. In virtue and meditation the soul had the power to elevate itself to attain union with the One, the true function of human beings. Non-Christian Neoplatonists used to attack Christianity until Christians such as Augustine, Boethius, and Eriugena adopt Neoplatonism.

See also

References

- A. A. Long, D. N. Sedley (eds.), The Hellenistic Philosophers (2 vols, Cambridge University Press, 1987)

- Giovanni Reale, The Systems of the Hellenistic Age: History of Ancient Philosophy (Suny Series in Philosophy), edited and translated from Italian by John R. Catan, Albany, State of New York University Press, 1985, ISBN 0887060080.

- Scholium on Aristotle's Rhetoric, quoted in Dudley 1937, p. 5

- Navia, Luis E. Classical Cynicism: A Critical Study. pg 140.

- Chauí, 2010, p. 14

- Chauí, 2010, p. 81

- FERGUSON, John. Cosmópolis. In: A Herança do Helenismo. Lisboa: Verbo, 1973, p. 35

- Abbagnano, 2014, p. 707.

- Eduard Zeller, Outlines of the History of Greek Philosophy, 13th Edition

- "Peripatetic philosophy" entry in Lieber, Wigglesworth & Bradford 1832, p. 22

- Chauí, 2010, p. 14

- Abbagnano, 2014, p. 826

- Abbagnano, 2014, p. 779

- https://web.archive.org/web/20150429142100/http://www.iep.utm.edu/eclectic/

- Abbagnano, 2014, p. 826

- "Platonism." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hellenistic philosophy. |

- The London Philosophy Study Guide offers many suggestions on what to read, depending on the student's familiarity with the subject: Post-Aristotelian philosophy

- "Readings in Hellenistic Philosophy" on PhilPapers, edited by Dirk Baltzly