Chakra

Chakra (Sanskrit: चक्र, IAST: cakra, Pali: cakka, lit. wheel, circle; English: /ˈtʃʌk-, ˈtʃækrə/ CHUK-, CHAK-rə[2]) are various focal points used in a variety of ancient meditation practices, collectively denominated as Tantra, or the esoteric or inner traditions of Hinduism.[3][4][5]

.jpg)

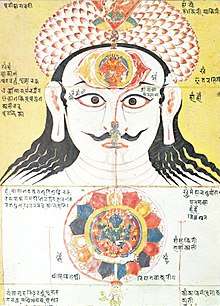

The concept is found in the early traditions of Hinduism.[6] Beliefs differ between the Indian religions, with many Buddhist texts consistently mentioning five chakras, while Hindu sources offer six or even seven.[7][3][4] Early Sanskrit texts speak of them both as meditative visualizations combining flowers and mantras and as physical entities in the body.[7] Some modern interpreters speak of them as complexes of electromagnetic variety, the precise degree and variety of which directly arise from a synthetic average of all positive and negative so-called "fields", thus eventuating the complex Nadi.[8][4] Within kundalini yoga, the techniques of breath exercises, visualizations, mudras, bandhas, kriyas, and mantras are focused on manipulating the flow of subtle energy through chakras.[9][6][10]

Etymology

Lexically, cakra is the Indic reflex of an ancestral Indo-European form *kʷékʷlos, whence also "wheel" and "cycle" (Ancient Greek κύκλος).[11][3][4] It has both literal[12] and metaphorical uses, as in the "wheel of time" or "wheel of dharma", such as in Rigveda hymn verse 1.164.11,[13][14] pervasive in the earliest Vedic texts.

In Buddhism, especially in Theravada, the Pali noun cakka connotes "wheel".[15] Within the central "Tripitaka", the Buddha variously refers the "dhammacakka", or "wheel of dharma", connoting that this dharma, universal in its advocacy, should bear the marks characteristic of any temporal dispensation. The Buddha spoke of freedom from cycles in and of themselves, whether karmic, reincarnative, liberative, cognitive or emotional.[16]

In Jainism, the term chakra also means "wheel" and appears in various contexts in its ancient literature.[17] As in other Indian religions, chakra in esoteric theories in Jainism such as those by Buddhisagarsuri means a yogic energy center.[18]

History

The term chakra appears to first emerge within the Hindu Vedas, though not precisely in the sense of psychic energy centers, rather as chakravartin or the king who "turns the wheel of his empire" in all directions from a center, representing his influence and power.[19] The iconography popular in representing the Chakras, states White, traces back to the five symbols of yajna, the Vedic fire altar: "square, circle, triangle, half moon and dumpling".[20]

The hymn 10.136 of the Rigveda mentions a renunciate yogi with a female named kunamnama. Literally, it means "she who is bent, coiled", representing both a minor goddess and one of many embedded enigmas and esoteric riddles within the Rigveda. Some scholars, such as David Gordon White and Georg Feuerstein, interpret this might be related to kundalini shakti, and an overt overture to the terms of esotericism that would later emerge in Post-Aryan Bramhanism. the Upanishad.[21][22][23]

Breath channels (nāḍi) are mentioned in the classical Upanishads of Hinduism from the 1st millennium BCE,[24][25] but not psychic-energy chakra theories. The latter, states David Gordon White, were introduced about 8th-century CE in Buddhist texts as hierarchies of inner energy centers, such as in the Hevajra Tantra and Caryāgiti.[24][26] These are called by various terms such as cakka, padma (lotus) or pitha (mound).[24] These medieval Buddhist texts mention only four chakras, while later Hindu texts such as the Kubjikāmata and Kaulajñānanirnaya expanded the list to many more.[24]

In contrast to White, according to Georg Feuerstein, early Upanishads of Hinduism do mention cakra in the sense of "psychospiritual vortices", along with other terms found in tantra: prana or vayu (life energy) along with nadi (energy carrying arteries).[22] According to Gavin Flood, the ancient texts do not present chakra and kundalini-style yoga theories although these words appear in the earliest Vedic literature in many contexts. The chakra in the sense of four or more vital energy centers appear in the medieval era Hindu and Buddhist texts.[27][24]

Overview

%2C_folio_2_from_the_Nath_Charit._Attributed_to_Bulaki%2C_1823_(Samvat_1880)%3B_46_x_122_cm._%C2%A9_Mehrangarh_Museum_Trust..jpg)

Shining, she holds

the noose made of the energy of will,

the hook which is energy of knowledge,

the bow and arrows made of energy of action.

Split into support and supported,

divided into eight, bearer of weapons,

arising from the chakra with eight points,

she has the ninefold chakra as a throne.

—Yoginihrdaya 53–54

(Translator: Andre Padoux)[28]

Chakra is a part of the esoteric medieval era beliefs about physiology and psychic centers that emerged across Indian traditions.[24][29] The belief held that human life simultaneously exists in two parallel dimensions, one "physical body" (sthula sarira) and other "psychological, emotional, mind, non-physical" it is called the "subtle body" (sukshma sarira).[30][note 1] This subtle body is energy, while the physical body is mass. The psyche or mind plane corresponds to and interacts with the body plane, and the belief holds that the body and the mind mutually affect each other.[5] The subtle body consists of nadi (energy channels) connected by nodes of psychic energy called chakra.[3] The belief grew into extensive elaboration, with some suggesting 88,000 chakras throughout the subtle body. The number of major chakras varied between various traditions, but they typically ranged between four and seven.[3][4]

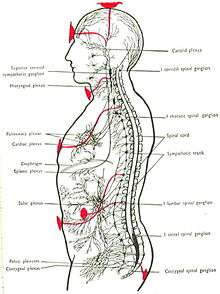

The important chakras are stated in Hindu and Buddhist texts to be arranged in a column along the spinal cord, from its base to the top of the head, connected by vertical channels.[5][6] The tantric traditions sought to master them, awaken and energize them through various breathing exercises or with assistance of a teacher. These chakras were also symbolically mapped to specific human physiological capacity, seed syllables (bija), sounds, subtle elements (tanmatra), in some cases deities, colors and other motifs.[3][5][32]

Belief in the chakra system of Hinduism and Buddhism differs from the historic Chinese system of meridians in acupuncture.[6] Unlike the latter, the chakra relates to subtle body, wherein it has a position but no definite nervous node or precise physical connection. The tantric systems envision it as continually present, highly relevant and a means to psychic and emotional energy. It is useful in a type of yogic rituals and meditative discovery of radiant inner energy (prana flows) and mind-body connections.[6][33] The meditation is aided by extensive symbology, mantras, diagrams, models (deity and mandala). The practitioner proceeds step by step from perceptible models, to increasingly abstract models where deity and external mandala are abandoned, inner self and internal mandalas are awakened.[34][35]

These ideas are not unique to Hindu and Buddhist traditions. Similar and overlapping concepts emerged in other cultures in the East and the West, and these are variously called by other names such as subtle body, spirit body, esoteric anatomy, sidereal body and etheric body.[36][37][31] According to Geoffrey Samuel and Jay Johnston, professors of Religious studies known for their studies on Yoga and esoteric traditions:

Ideas and practices involving so-called 'subtle bodies' have existed for many centuries in many parts of the world. (...) Virtually all human cultures known to us have some kind of concept of mind, spirit or soul as distinct from the physical body, if only to explain experiences such as sleep and dreaming. (...) An important subset of subtle-body practices, found particularly in Indian and Tibetan Tantric traditions, and in similar Chinese practices, involves the idea of an internal 'subtle physiology' of the body (or rather of the body-mind complex) made up of channels through which substances of some kind flow, and points of intersection at which these channels come together. In the Indian tradition the channels are known as nadi and the points of intersection as cakra.

— Geoffrey Samuel and Jay Johnston, Religion and the Subtle Body in Asia and the West: Between Mind and Body[38]

Contrast with classical yoga

Chakra and related beliefs have been important to the esoteric traditions, but they are not directly related to mainstream yoga. According to the Indologist Edwin Bryant and other scholars, the goals of classical yoga such as spiritual liberation (freedom, self-knowledge, moksha) is "attained entirely differently in classical yoga, and the cakra / nadi / kundalini physiology is completely peripheral to it."[39][40]

Classical traditions

The classical eastern traditions, particularly those that developed in India during the 1st millennium AD, primarily describe nadi and cakra in a "subtle body" context.[41] To them, they are in same dimension as of the psyche-mind reality that is invisible yet real. In the nadi and cakra flow the prana (breath, life energy).[41][42] The concept of "life energy" varies between the texts, ranging from simple inhalation-exhalation to far more complex association with breath-mind-emotions-sexual energy.[41] This prana or essence is what vanishes when a person dies, leaving a gross body. Some of this concept states this subtle body is what withdraws within, when one sleeps. All of it is believed to be reachable, awake-able and important for an individual's body-mind health, and how one relates to other people in one's life.[41] This subtle body network of nadi and chakra is, according to some later Indian theories and many new age speculations, closely associated with emotions.[41][43]

Hindu Tantra

Different esoteric traditions in Hinduism mention numerous numbers and arrangements chakras, of which a classical system of seven is most prevalent.[3][4][5] This seven-part system, central to the core texts of hatha yoga, is one among many systems found in Hindu tantric literature. These texts teach many different Chakra theories.[44]

The Chakra methodology is extensively developed in the goddess tradition of Hinduism called Shaktism. It is an important concept along with yantras, mandalas and kundalini yoga in its practice. Chakra in Shakta tantrism means circle, an "energy center" within, as well as being a term for group rituals such as in chakra-puja (worship within a circle) which may or may not involve tantra practice.[45] The cakra-based system is a part of the meditative exercises that came to be known as yoga.[46]

Beyond its original Shakta milieu, various sub-traditions within the Shaiva and Vaishnava schools of Hinduism also developed texts and practices on Nadi and Chakra systems. Modern Hindu groups including the Bihar School of Yoga and the Self Realization Fellowship utilize a technique of circular energy that works based on the chakras known as kriya yoga. Although Paramahansa Yogananda claimed this was the same technique taught as kriya yoga by Patañjali in the Yoga Sūtras and by Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita (as karma yoga), Swami Satyananda of the Bihar school disagreed with this assessment and acknowledged the similarities between kriya and taoist inner orbit practices. Both schools claim the technique is taught in every age by an avatar of god known as Babaji. The historicity of its techniques in India prior to the early twentieth century are not well established. It believed by its practitioners to activate the chakras and stimulate faster spiritual development.

Buddhist Tantra

.jpg)

The esoteric traditions in Buddhism generally teach four chakras.[3] In some early Buddhist sources, these chakras are identified as: manipura (navel), anahata (heart), vishuddha (throat) and ushnisha kamala (crown).[48][49] In one development within the Nyingma lineage of the Mantrayana of Tibetan Buddhism a popular conceptualization of chakras in increasing subtlety and increasing order is as follows: Nirmanakaya (gross self), Sambhogakaya (subtle self), Dharmakaya (causal self), and Mahasukhakaya (non-dual self), each vaguely – yet by no means directly – corresponding to the categories within the Shaiva Mantramarga universe, i.e., Svadhisthana, Anahata, Visuddha, Sahasrara, etc.[50] However, depending on the meditational tradition, these vary between three and six.[48] The chakras are considered psycho-spiritual constituents, each bearing meaningful correspondences to cosmic processes and their postulated Buddha counterpart.[51][48]

A system of five chakras is common among the Mother class of Tantras and these five chakras along with their correspondences are:[52]

- Basal chakra (Element: Earth, Buddha: Amoghasiddhi, Bija mantra: LAM)

- Abdominal chakra (Element: Water, Buddha: Ratnasambhava, Bija mantra: VAM)

- Heart chakra (Element: Fire, Buddha: Akshobhya, Bija mantra: RAM)

- Throat chakra (Element: Wind, Buddha: Amitabha, Bija mantra: YAM)

- Crown chakra (Element: Space, Buddha: Vairochana, Bija mantra: KHAM)

Chakras clearly play a key role in Tibetan Buddhism, and are considered to be the pivotal providence of Tantric thinking. And, the precise use of the chakras across the gamut of tantric sadhanas gives little space to doubt the primary efficacy of Tibetan Buddhism as distinct religious agency, that being that precise revelation that, without Tantra there would be no Chakras, but more importantly, without Chakras, there is no Tibetan Buddhism. The highest practices in Tibetan Buddhism point to the ability to bring the subtle pranas of an entity into alignment with the central channel, and to thus penetrate the realisation of the ultimate unity, namely, the "organic harmony" of one's individual consciousness of Wisdom with the co-attainment of All-embracing Love, thus synthesizing a direct cognition of absolute Buddhahood.[53]

According to Geoffrey Samuel, the buddhist esoteric systems developed cakra and nadi as "central to their soteriological process".[54] The theories were sometimes, but not always, coupled with a unique system of physical exercises, called yantra yoga or 'phrul 'khor.

Chakras, according to the Bon tradition, enable the gestalt of experience, with each of the five major chakras, being psychologically linked with the five experiential qualities of unenlightened consciousness, the six realms of woe.[55]

The tsa lung practice embodied in the Trul khor lineage, unbaffles the primary channels, thus activating and circulating liberating prana. Yoga awakens the deep mind, thus bringing forth positive attributes, inherent gestalts, and virtuous qualities. In a computer analogy, the screen of one's consciousness is slated and an attribute-bearing file is called up that contains necessary positive or negative, supportive qualities.[56][57]

Tantric practice is said to eventually transform all experience into clear light. The practice aims to liberate from all negative conditioning, and the deep cognitive salvation of freedom from control and unity of perception and cognition.[56]

Qigong

Qigong (氣功) also relies on a similar model of the human body as an esoteric energy system, except that it involves the circulation of qì (氣, also ki) or life-energy.[58][59] The qì, equivalent to the Hindu prana, flows through the energy channels called meridians, equivalent to the nadi, but two other energies are also important: jīng, or primordial essence, and shén, or spirit energy.

In the principle circuit of qì, called the microcosmic orbit, energy rises up a main meridian along the spine, but also comes back down the front torso. Throughout its cycle it enters various dantian (elixir fields) which act as furnaces, where the types of energy in the body (jing, qi and shen) are progressively refined.[60] These dantian play a very similar role to that of chakras. The number of dantian varies depending on the system; the navel dantian is the most well-known, but there is usually a dantian located at the heart and between the eyebrows.[61] The lower dantian at or below the navel transforms essence, or jīng, into qì. The middle dantian in the middle of the chest transforms qì into shén, or spirit, and the higher dantian at the level of the forehead (or at the top of the head), transforms shen into wuji, infinite space of void.[62]

Silat

Traditional spirituality in the Malay Archipelago borrows heavily from Hindu-Buddhist concepts. In Malay and Indonesian metaphysical theory, the chakras' energy rotates outwards along diagonal lines. Defensive energy emits outwards from the centre line, while offensive energy moves inwards from the sides of the body. This can be applied to energy-healing, meditation, or martial arts. Silat practitioners aim to harmonise their movements with these chakras, thereby increasing the power and effectiveness of attacks and movements.[63]

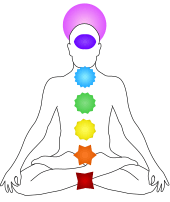

The seven chakra system

The more common and most studied chakra system incorporates six major chakras along with a seventh center generally not regarded as a chakra. These points are arranged vertically along the axial channel (sushumna nadi in Hindu texts, Avadhuti in some Buddhist texts).[64] According to Gavin Flood, this system of six chakras plus the sahasrara "center" at the crown first appears in the Kubjikāmata-tantra, an 11th-century Kaula work.[65]

It was this chakra system that was translated in the early 20th century by Sir John Woodroffe (also called Arthur Avalon) in the text The Serpent Power. Avalon translated the Hindu text Ṣaṭ-Cakra-Nirūpaṇa meaning the examination (nirūpaṇa) of the six (ṣaṭ) chakras (cakra).[66]

The Chakras are traditionally considered meditation aids. The yogi progresses from lower chakras to the highest chakra blossoming in the crown of the head, internalizing the journey of spiritual ascent.[67] In both the Hindu and Buddhist kundalini or candali traditions, the chakras are pierced by a dormant energy residing near or in the lowest chakra. In Hindu texts she is known as Kundalini, while in Buddhist texts she is called Candali or Tummo (Tibetan: gtum mo, "fierce one").[68]

Below are the common new age description of these six chakras and the seventh point known as sahasrara. This new age version incorporates the Newtonian colors that were unknown when these systems were created.

| Image of chakra | Name | Sanskrit | Translation | Location | No. of lotus petals | Modern colour | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sahasrara or Sahastrar | सहस्रार | "Thousand-petaled" | Crown | 1000 | Multi-coloured or violet | Highest spiritual centre, pure consciousness, containing neither object nor subject. When the feminine Kundalini Shakti rises to this point, it unites with the masculine Shiva, giving self-realization and samadhi.[69] In esoteric Buddhism, it is called Mahasukha, the petal lotus of "Great Bliss" corresponding to the fourth state of Four Noble Truths.[68] |

| Ajna or Agya | आज्ञा | "Command" | Between eyebrows | 2 | Indigo | Guru chakra or third-eye chakra, the subtle center of energy, where the tantra guru touches the seeker during the initiation ritual (saktipata). He or she commands the awakened kundalini to pass through this centre.[70] |

| Vishuddha | विशुद्ध | "Purest" | Throat | 16 | Blue | The Vishuddha is iconographically represented with 16 petals covered with the sixteen Sanskrit vowels. It is associated with the element of space (akasha) and has the seed syllable of the space element Ham at its centre. The residing deity is Panchavaktra shiva, with 5 heads and 4 arms, and the Shakti is Shakini.[4]

In esoteric Buddhism, it is called Sambhoga and is generally considered to be the petal lotus of "Enjoyment" corresponding to the third state of Four Noble Truths.[68] |

| Anahata | अनाहत | "Unstruck" | Heart | 12 | Green | Within it is a yantra of two intersecting triangles, forming a hexagram, symbolising a union of the male and female as well as being the esoteric symbol for the element of air (vayu). The seed mantra of air, Yam, is at its centre. The presiding deity is Ishana Rudra Shiva, and the Shakti is Kakini.[71]

In esoteric Buddhism, this Chakra is called Dharma and is generally considered to be the petal lotus of "Essential nature" and corresponding to the second state of Four Noble Truths.[68] |

| Manipura | मणिपूर | "Jewel city" | Navel | 10 | Yellow | For the Nath yogi meditation system, this is described as the Madhyama-Shakti or the intermediate stage of self-discovery.[67] This chakra is represented as a downward pointing triangle representing fire in the middle of a lotus with ten petals. The seed syllable for fire is at its center Ram. The presiding deity is Braddha Rudra, with Lakini as the Shakti.[4] |

| Svadhishthana | स्वाधिष्ठान | "Where the self is established" | Root of sexual organs | 6 | Orange | Svadhisthana is represented with a lotus within which is a crescent moon symbolizing the water element. The seed mantra in its center is Vam representing water. The presiding deity is Brahma, with the Shakti being Rakini (or Chakini).[4]

In esoteric Buddhism, it is called Nirmana, the petal lotus of "Creation" and corresponding to the first state of Four Noble Truths.[68] |

| Muladhara | मूलाधार | "Root" | Base of spine | 4 | Red | Dormant Kundalini is often said to be resting here, wrapped three and a half, or seven or twelve times. Sometimes she is wrapped around the black Svayambhu linga, the lowest of three obstructions to her full rising (also known as knots or granthis).[72] It is symbolised as a four-petaled lotus with a yellow square at its center representing the element of earth.[4]

The seed syllable is Lam for the earth element (pronounced lum),. All sounds, words and mantras in their dormant form rest in the muladhara chakra, where Ganesha resides,[73] while the Shakti is Dakini.[74] The associated animal is the elephant.[75] |

Other chakras

| Tantric chakras |

|---|

Many systems include myriad minor chakras throughout the body. Talu, bindu, manas, and dvadashanta chakra are close to and associated with Ajna chakra. Situated just to the left of Anahata chakra (where the heart is situated anatomically) is Hridaya chakra. Lalance chakra is situated at the base of the mouth and is associated with Vishuddha chakra. In some Shaivist traditions there are 114 chakras out of which 112 are present inside the body.[76]

Reception and introduction into the West

In 1918, the translation of two Indian texts—the Ṣaṭ-Cakra-Nirūpaṇa and the Pādukā-Pañcaka, by Sir John Woodroffe, alias Arthur Avalon, in a book titled The Serpent Power—introduced the shakta theory of seven main chakras in the West.[77] This book is extremely detailed and complex, and later the ideas were developed into the predominant Western view of the chakras by C. W. Leadbeater in his book The Chakras. Many of the views which directed Leadbeater's understanding of the chakras were influenced by previous theosophist authors, in particular Johann Georg Gichtel, a disciple of Jakob Böhme, and his book Theosophia Practica (1696), in which Gichtel directly refers to inner force centres, a concept reminiscent of the chakras.[78]

Hesychasm

A separate contemplative movement within the Eastern Orthodox Church is Hesychasm, a form of Christian meditation. Comparisons have been made between the Hesychastic centres of prayer and the position of the chakras.[79] Particular emphasis is placed upon the heart area. However, there is no talk about these centres as having any sort of metaphysical existence. Far more than in any of the cases discussed above, the centres are simply places to focus the concentration during prayer.

New Age

In Anatomy of the Spirit (1996), Caroline Myss describes the function of chakras as follows: "Every thought and experience you've ever had in your life gets filtered through these chakra databases. Each event is recorded into your cells...".[80] The chakras are described as being aligned in an ascending column from the base of the spine to the top of the head. New Age practices often associate each chakra with a certain colour. In various traditions, chakras are associated with multiple physiological functions, an aspect of consciousness, a classical element, and other distinguishing characteristics. They are visualised as lotuses or flowers with a different number of petals in every chakra.

The chakras are thought to vitalise the physical body and to be associated with interactions of a physical, emotional and mental nature. They are considered loci of life energy or prana (which New Age belief equates with shakti, qi in Chinese, ki in Japanese, koach-ha-guf[81] in Hebrew, bios in Greek, and aether in both Greek and English), which is thought to flow among them along pathways called nadi. The function of the chakras is to spin and draw in this energy to keep the spiritual, mental, emotional and physical health of the body in balance.[82]

Rudolf Steiner considered the chakra system to be dynamic and evolving. He suggested that this system has become different for modern people than it was in ancient times and that it will, in turn, be radically different in future times.[83][84][85] Steiner described a sequence of development that begins with the upper chakras and moves down, rather than moving in the opposite direction. He gave suggestions on how to develop the chakras through disciplining thoughts, feelings, and will.[86]

According to Florin Lowndes, a "spiritual student" can further develop and deepen or elevate thinking consciousness when taking the step from the "ancient path" of schooling to the "new path" represented by Steiner's The Philosophy of Freedom.[87]

Supposed physical counterparts

Although chakras are posited to reside in the psyche, authors such as Gary Osborn have called the chakras metaphysical counterparts to the endocrine glands.[88] Anodea Judith asserted that the positions and roles of the two were similar.[89] Stephen Sturgess also links the lower six chakras to specific nerve plexuses along the spinal cord as well as glands.[90] C. W. Leadbeater associated the Ajna chakra with the pineal gland,[91] which is a part of the endocrine system.[92]

See also

- Aura

- Lataif-e-sitta

- Meridian (Chinese medicine)

- Sudarshana Chakra

- Surya Namaskar—the Sun Salutation, in which each posture is sometimes associated with a chakra and a mantra

- Seven Factors of Awakening

- Classical planet

- Seven churches of Asia

- List of Mesopotamian deities#Seven planetary deities

Notes

- The roots to this belief are found in Samkhya and Vedanta which attempt to conceptualize the permanent soul and impermanent body as interacting in three overlapping states: the gross body (sthula sarira), the subtle body (sukshma sarira), and causal body (karana sarira). These ideas emerged to address questions relating to the nature of body and soul, how and why they interact while one is awake, one is asleep and over the conception-birth-growth-decay-death-rebirth cycle.[30][31]

Citations

- Sapta Chakra, The British Library, MS 24099

- Wells, John (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Chakra: Religion, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Grimes, John A (1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-0-7914-3067-5.

- Lochtefeld, James G (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- Heilijgers-Seelen, Dory (1992). The system of five cakras in Kubjikāmatatantra 14–16: a study and annotated translation (Thesis). S.l.: s.n.] OCLC 905777672.

- Wendy, Doniger (2006). Britannica Encyclopedia of World Religions. Encyclopaedia Britannica. ISBN 9781593394912. OCLC 319493641.

- https://www.shrisanatana.co/2019/08/seven-chakras.html

- Beer, Robert (2003). The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Serindia Publications. pp. 242–243. ISBN 978-1-932476-03-3.

- Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture (1 ed.). Routledge. p. 640. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Staal, Frits (2008). Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights. Penguin Books. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-14-309986-4.

- Staal, Frits (2008). Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights. Penguin Books. pp. 333–335. ISBN 978-0-14-309986-4.

- ऋग्वेद: सूक्तं १.१६४, verse ॥११॥, Rigveda, Wikisource

- Steven Collins (1998). Nirvana and Other Buddhist Felicities. Cambridge University Press. pp. 473–474. ISBN 978-0-521-57054-1.

- Edgerton, Franklin (1993). Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Grammar and Dictionary (Repr ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 221. ISBN 81-208-0999-8.

- Helmuth von Glasenapp (1925). Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 280–283, 427–428, 476–477. ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2.

- White, David Gordon (2001). Tantra in Practice. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 426–427. ISBN 978-81-208-1778-4.

- White, David Gordon (2001). Tantra in Practice. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 25. ISBN 978-81-208-1778-4.

- White, David Gordon (2001). Tantra in Practice. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 555. ISBN 978-81-208-1778-4.

- David Gordon White (2006). Kiss of the Yogini: "Tantric Sex" in its South Asian Contexts. University of Chicago Press. pp. 33, 130, 198. ISBN 978-0-226-02783-8.

- Feuerstein, Georg (1998). Tantra: Path of Ecstasy. Shambhala Publications. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-8348-2545-1.

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–78, 285. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- White, David Gordon. Yoga in Practice. Princeton University Press 2012, pages 14–15.

- Trish O'Sullivan (2010), Chakras. In: D.A. Leeming, K. Madden, S. Marlan (eds.), Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion, Springer Science + Business Media.

- White, David Gordon (2003). Kiss of the Yogini. University of Chicago Press. p. 224. ISBN 0-226-89483-5.

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–100. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- Andre Padoux (2013). The Heart of the Yogini: The Yoginihrdaya, a Sanskrit Tantric Treatise. Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-19-998233-2.

- Basant Pradhan (2014). Yoga and Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy: A Clinical Guide. Springer. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-3-319-09105-1.

- Arvind Sharma (2006). A Primal Perspective on the Philosophy of Religion. Springer. pp. 193–196. ISBN 978-1-4020-5014-5.

- Friedrich Max Müller (1899). The Six Systems of Indian Philosophy. Longmans. pp. 227–236, 393–395.

- Klaus K. Klostermaier (2010). Survey of Hinduism, A: Third Edition. State University of New York Press. pp. 238–243. ISBN 978-0-7914-8011-3.

- Peter Harvey (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices, 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 190–191, 353–357. ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4.

- E. A. Mayer; C. B. Saper (2000). The Biological Basis for Mind Body Interactions. Elsevier. pp. 514–516. ISBN 978-0-08-086247-7.

- Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 735–740. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0.

- Jay Johnston (2010). Elizabeth Burns Coleman and Kevin White (ed.). Medicine, Religion, and the Body. BRILL Academic. pp. 69–75. ISBN 978-90-04-17970-7.

- Christine Göttler; Wolfgang Neuber (2008). Spirits Unseen: The Representation of Subtle Bodies in Early Modern European Culture. BRILL Academic. pp. 55–58, 294–300. ISBN 978-90-04-16396-6.

- Geoffrey Samuel; Jay Johnston (2013). Religion and the Subtle Body in Asia and the West: Between Mind and Body. Routledge. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-136-76640-4.

- Edwin Francis Bryant (2009). The Yoga sūtras of Patañjali: a new edition, translation, and commentary with insights from the traditional commentators. North Point Press. pp. 358–364, 229–233. ISBN 978-0-86547-736-0.

- Stefanie Syman (2010). The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 72–74. ISBN 978-1-4299-3307-0.

- Geoffrey Samuel; Jay Johnston (2013). Religion and the Subtle Body in Asia and the West: Between Mind and Body. Routledge. pp. 5–8, 38–45, 187–190. ISBN 978-1-136-76640-4.

- Adrian Snodgrass (1992). The Symbolism of the Stupa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 317–319. ISBN 978-81-208-0781-5.

- Harish Johari (2000). Chakras: Energy Centers of Transformation. Inner Traditions. pp. 21–36. ISBN 978-1-59477-909-1.

- White, David Gordon (2003). Kiss of the Yogini. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 221–229. ISBN 0-226-89483-5.

- June McDaniel (2004). Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal. Oxford University Press. pp. 96–97, 101–123. ISBN 978-0-19-534713-5.

- Philipp H. Pott (2013). Yoga and Yantra: Their Interrelation and Their Significance for Indian Archaeology. Springer. pp. 8–12. ISBN 978-94-017-5868-0.

- John C. Huntington; Dina Bangdel (2003). The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Serindia Publications. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-1932476019.

- Carl Olson (2009). Historical Dictionary of Buddhism. Scarecrow Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8108-6317-0.

- Alternate Sanskrit terms can be found at http://malankazlev.com/kheper/topics/chakras/chakras-Tib.htm .

- Geoffrey Samuel; Jay Johnston (2013). Religion and the Subtle Body in Asia and the West: Between Mind and Body. Routledge. p. 40, Table 2.1. ISBN 978-1-136-76640-4.

- Rory Mackenzie (2007). New Buddhist Movements in Thailand: Towards an Understanding of Wat Phra Dhammakaya and Santi Asoke. Routledge. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-1-134-13262-1.

- John C. Huntington, Dina Bangdel, The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art, Serindia Publications, Inc., 2003, p. 231.

- Geshe Gelsang Kyatos, Clear Light of Bliss.

- Geoffrey Samuel; Jay Johnston (2013). Religion and the Subtle Body in Asia and the West: Between Mind and Body. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-136-76640-4.

- Dahlby, Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche (2002). Mark (ed.). Healing with Form, Energy, and Light: The Five Elements in Tibetan Shamanism, Tantra, and Dzogchen. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion. p. 84. ISBN 1-55939-176-6.

- Rinpoche, Tenzin Wangyal (2002). Healing with Form, Energy, and Light: the five elements in Tibetan Shamanism, Tantra, and Dzogchen. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion. pp. 84–85. ISBN 1-55939-176-6.

- Dahlby, Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche ; edited by Mark (2002). Healing with Form, Energy, and Light: the five elements in Tibetan Shamanism, Tantra, and Dzogchen. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion. pp. 84–85. ISBN 1-55939-176-6.

- Charles Luk, Taoist Yoga – Alchemy and Immortality, Rider and Company, London, 1970

- Mantak and Maneewan Chia Awaken Healing Light of the Tao (Healing Tao Books, 1993), ch.5

- Yang Erzeng, Philip Clart. The Story of Han Xiangzi: the alchemical adventures of a Taoist immortal

- Mantak and Maneewan Chia Awaken Healing Light of the Tao (Healing Tao Books, 1993), ch.13

- Andy James. The Spiritual Legacy of Shaolin Temple

- Zainal Abidin Shaikh Awab and Nigel Sutton (2006). Silat Tua: The Malay Dance of Life. Kuala Lumpur: Azlan Ghanie Sdn Bhd. ISBN 978-983-42328-0-1.

- Geoffrey Samuel; Jay Johnston (2013). Religion and the Subtle Body in Asia and the West: Between Mind and Body. Routledge. pp. 39–42. ISBN 978-1-136-76640-4.

- Flood, Gavin (2006). The Tantric Body: The Secret Tradition of Hindu Religion. I.B.Tauris. p. 157. ISBN 978-1845110123.

- White, David Gordon (2003). Kiss of the Yogini. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 221. ISBN 0-226-89483-5.

- Akshaya Kumar Banerjea (1983). Philosophy of Gorakhnath with Goraksha-Vacana-Sangraha. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 175–184. ISBN 978-81-208-0534-7.

- Geoffrey Samuel; Jay Johnston (2013). Religion and the Subtle Body in Asia and the West: Between Mind and Body. Routledge. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-1-136-76640-4.

- John A. Grimes (1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. pp. 265, 100–101. ISBN 978-0-7914-3067-5.

- John A. Grimes (1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. pp. 22, 100–101. ISBN 978-0-7914-3067-5.

- John A. Grimes (1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7914-3067-5.

- Brown, C. Mackenzie (1998). The Devī Gītā: the Song of the Goddess: a translation, annotation, and commentary. Albany (N.Y.): State university of New York press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-7914-3940-1.

- Tigunait, Rajmani (1999). Tantra Unveiled: Seducing the Forces of Matter & Spirit. Himalayan Institute Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780893891589.

- Mumford, John (1988). Ecstasy Through Tantra (Third ed.). Llewellyn Worldwide. p. 72. ISBN 0-87542-494-5.

- Mindell, Arnold; Sternback-Scott, Sisa; Goodman, Becky (1984). Dreambody: the body's rôle in revealing the self. Taylor & Francis. p. 38. ISBN 0-7102-0250-4.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y_VL19SScV8&t=538s

- Woodroffe, The Serpent Power, Dover Publications, pp.317ff

- Archived 4 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Mircea Eliade. Yoga, Immortality and Freedom

- "Myss Library | Chakras". Myss.com. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Helena Blavatsky (1892). Theosophical Glossary. Krotona.

- Neff, Dio Urmilla (1985). "The Great Chakra Controversy". Yoga Journal (Nov–Dec 1985): 42–45, 50–53.

- "GA010: Chapter I: The Astral Centers". Fremont, Michigan. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- http://wn.rsarchive.org/Books/GA010/English/MAC1909/GA010b_index.html

- "GA010: Initiation and Its Results". Fremont, Michigan. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- Rudolf Steiner, How to Know Higher Worlds

- Lowndes, Florin (2000). Enlivening the Chakra of the Heart: The Fundamental Spiritual Exercises of Rudolf Steiner (2nd ed.). London: Sophia Books. ISBN 1-85584-053-7.

- Gardiner, Philip; Osborn, Gary (2006). The Shining Ones: the world's most powerful secret society revealed (Rev. and updated ed.). London: Watkins. pp. 44–45. ISBN 1-84293-150-4.

- Judith, Anodea (1999). Wheels of Life: A User's Guide to the Chakra System. p. 20. ISBN 9780875423203.

- Sturgess, Stephen (1997). The Yoga Book: a practical guide to self-realization. Rockport, Mass.: Element. pp. 19–21. ISBN 1-85230-972-5.

- Charles Webster Leadbeater (1972). The Chakras. Theosophical Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-8356-0422-2.

- "John Van Auken | Mysticism - Interpretating the Revelation". Edgarcayce.org. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

Further reading

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965). The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary (fourth revised & enlarged ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-0567-4.

- Bucknell, Roderick; Stuart-Fox, Martin (1986). The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism. London: Curzon Press. ISBN 0-312-82540-4.

- Edgerton, Franklin (2004) [1953]. Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Grammar and Dictionary (Reprint ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-0999-8. (Two volumes)

- Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43878-0.

- Chia, Mantak; Chia, Maneewan (1993). Awaken Healing Light of the Tao. Healing Tao Books.

- Dale, Cyndi (2009). The Subtle Body: An Encyclopedia of Your Energetic Anatomy. Boulder, CO: Sounds True. ISBN 978-1-59179-671-8.

- Monier-Williams, Monier. A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

- Prabhananda, S. (2000). Studies on the Tantras (Second reprint ed.). Calcutta: The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture. ISBN 81-85843-36-8.

- Rinpoche, Tenzin Wangyal (2002). Healing with Form, Energy, and Light. Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 1-55939-176-6.

- Saraswati, MD, Swami Sivananda (1953–2001). Kundalini Yoga. Tehri-Garhwal, India: Divine Life Society. foldout chart. ISBN 81-7052-052-5.

- Tulku, Tarthang (2007). Tibetan Relaxation. The illustrated guide to Kum Nye massage and movement – A yoga from the Tibetan tradition. London: Dunkan Baird Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84483-404-4.

- Woodroffe, John (1919–1964). The Serpent Power. Madras, India: Ganesh & Co. ISBN 0-486-23058-9.

- Banerji, S. C. Tantra in Bengal. Second Revised and Enlarged Edition. (Manohar: Delhi, 1992) ISBN 81-85425-63-9

- Saraswati, Swami Sivananda, MD (1953–2001). Kundalini Yoga. Tehri-Garhwal, India: Divine Life Society. ISBN 81-7052-052-5.

- Shyam Sundar Goswami, Layayoga: The Definitive Guide to the Chakras and Kundalini, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980.

- Leadbeater, C.W. The Chakras Wheaton, Illinois, USA:1926—Theosophical Publishing House—Picture of the Chakras on plates facing page 17 as claimed to have been observed by Leadbeater with his third eye

- Sharp, Michael (2005). Dossier of the Ascension: A Practical Guide to Chakra Activation and Kundalini Awakening (1st ed.). Avatar Publications. ISBN 0-9735379-3-0. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Guru Dharam Singh Khalsa and Darryl O'Keeffe. The Kundalini Yoga Experience New York, NY USA:2002, Fireside, Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright by Gaia Books Limited. Kriyas and meditations copyright Yogi Bhajan, All Rights reserved. Revised Edition published 2016 as "Kundalini Yoga" ISBN 978-1-85675-359-3

- Judith, Anodea (1996). Eastern Body Western Mind: Psychology and the Chakra System As A Path to the Self. Berkeley, California, USA: Celestial Arts Publishing. ISBN 0-89087-815-3

- Dahlheimer, Volker (2006). Kundalini Shakti: Explanation of the Seven Chakras (Video clip with words and explanative grafics ed.). 5th Level Publications.

- Florin Lowndes, 'Enlivening the Chakra of the Heart: The Fundamental Spiritual Exercises of Rudolf Steiner' ISBN 1-85584-053-7, first English edition 1998 from the original German edition of 1996, comparing 'traditional' chakra teaching, and that of C.W.Leadbeater, with that of Rudolf Steiner.

External links

| Look up Chakra in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chakras. |