Moinuddin Chishti

Chishtī Muʿīn al-Dīn Ḥasan Sijzī (1143–1236 CE), known more commonly as Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī or Moinuddin Chishti[6] or Khwājā Ghareeb Nawaz, or reverently as a Shaykh Muʿīn al-Dīn or Muʿīn al-Dīn or Khwājā Muʿīn al-Dīn ( In Urdu خواجہ معین الدین چشتی المعروف خواجہ غریب نواز ) by Muslims of the Indian subcontinent, was a Persian Muslim[3] preacher,[6] ascetic, religious scholar, philosopher, and mystic from Sistan,[6] who eventually ended up settling in the Indian subcontinent in the early 13th-century, where he promulgated the famous Chishtiyya order of Sunni mysticism.[6][7] This particular tariqa (order) became the dominant Muslim spiritual group in medieval India and many of the most beloved and venerated Indian Sunni saints[4][8][9] were Chishti in their affiliation, including Nizamuddin Awliya (d. 1325) and Amir Khusrow (d. 1325).[6] As such, Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī's legacy rests primarily on his having been "one of the most outstanding figures in the annals of Islamic mysticism."[2] Additionally Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī is also notable, according to John Esposito, for having been one of the first major Islamic mystics to formally allow his followers to incorporate the "use of music" in their devotions, liturgies, and hymns to God, which he did in order to make the foreign Arab faith more relatable to the indigenous peoples who had recently entered the religion or whom he sought to convert.[10] Others contest that the Chisti order ever permitted musical instruments and a famous Chisti, Nizamuddin Auliya, is quoted as stating that musical instruments are prohibited.[11][12][13]

Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī | |

|---|---|

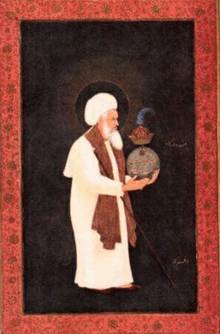

A Mughal miniature representing Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī | |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1 February 1143 CE |

| Died | 15 March 1236 CE (aged 93) |

| Resting place | Ajmer Sharif Dargah |

| Religion | Islam |

| Flourished | Islamic golden age |

| Denomination | Sunni[3][4] |

| Jurisprudence | Hanafi |

| Creed | Maturidi |

| Tariqa | Chisti |

| Muslim leader | |

| Teacher | Usman Harooni, ʿAbdullah Ansari,[5] Najīb al-Dīn Nakhshabī[5] |

Although little is known of Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī's early life, it is probable that he travelled from Sistan to India to seek refuge from the increasing prevalence of Mongol military action in central Asia at that point in time.[6] Having arrived in Delhi during the reign of the sultan Iltutmish (d. 1236), Muʿīn al-Dīn moved from Delhi to Ajmer shortly thereafter, at which point he became increasingly influenced by the writings of the famous Sunni Hanbali scholar and mystic ʿAbdallāh Anṣārī (d. 1088), whose famous work on the lives of the early Islamic saints, the Ṭabāqāt al-ṣūfiyya, may have played a role in shaping Muʿīn al-Dīn's worldview.[6] It was during his time in Ajmer that Muʿīn al-Dīn acquired the reputation of being a charismatic and compassionate spiritual preacher and teacher; and biographical accounts of his life written after his death report that he received the gifts of many "spiritual marvels (karāmāt), such as miraculous travel, clairvoyance, and visions of angels"[6][14] in these years of his life. Muʿīn al-Dīn seems to have been unanimously regarded as a great saint after his passing.[6]

Life

Born in 1143 in Sistan, Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī was a teenager when his father, Sayyid G̲h̲iyāt̲h̲ al-Dīn (d. c. 1155), died,[2] with the latter leaving his grinding mill and orchard to his son.[2] His father, Ghayasuddin, and mother, Bibi Ummalwara (alias Bibi Mahe-Noor), were the descendants of Ali, through his sons Hassan and Hussain.[15] He lost both his parents at an early age of sixteen years.[15] Although he was initially hoping to continue his father's business,[2] the Mongol conquests in the region seem to have "turned his mind inwards,"[2] whence he soon began to develop strong contemplative and mystic tendencies in his personal piety.[2] Soon after, Muʿīn al-Dīn gave away all of his financial assets, and began a life of destitute itineracy, wandering in search of knowledge and wisdom throughout the neighbouring quarters of the Islamic world. As such, he visited the famous seminaries of Bukhara and Samarkand, "and acquired religious learning at the feet of eminent scholars of his age."[2] It is also entirely probable that he visited the shrines of Muhammad al-Bukhari (d. 870) and Abu Mansur al-Maturidi (d. 944) during his travels in this region, who were both widely venerated figures in the Islamic world by this point in time.[2]

While travelling to Iraq, the young Muʿīn al-Dīn encountered in the district of Nishapur the famous Sunni saint and mystic Ḵh̲wāj̲a ʿUt̲h̲mān (d. c. 1200), who initiated the willing seeker into his circle of disciples.[2] Accompanying his spiritual guide for over twenty years on the latter's journeys from region to region, Muʿīn al-Dīn also continued his own independent spiritual travels during the time period.[2] It was on his independent wanderings that Muʿīn al-Dīn encountered many of the most notable Sunni mystics of the era, including Abdul-Qadir Gilani (d. 1166) and Najmuddin Kubra (d. 1221), as well as Naj̲īb al-Dīn ʿAbd al-Ḳāhir Suhrawardī, Abū Saʿīd Tabrīzī, and ʿAbd al-Waḥid G̲h̲aznawī (all d. c. 1230), all of whom were destined to become some of the most highly venerated saints in the Sunni tradition.[2] Due to Muʿīn al-Dīn's subsequent visits to "nearly all the great centers of Muslim culture in those days," including Bukhara, Samarkand, Nishapur, Baghdad, Tabriz, Isfahan, Balkh, Ghazni, Astarabad, and many others, the preacher and mystic eventually "acquainted himself with almost every important trend in Muslim religious life in the middle ages."[2]

Arrival in Lahore

Arriving in India in the early thirteenth century, Muʿīn al-Dīn first travelled to Lahore to meditate at the tomb-shrine of the famous Sunni mystic and jurist Ali Hujwiri (d. 1072),[2] who was venerated by the Sunnis of the area as the patron saint of that city.[2] From Lahore, Muʿīn al-Dīn continued forward on his journey towards Ajmer, which he reached prior to the city's conquest by the Ghurids.[2] It was in Ajmer that Muʿīn al-Dīn got married at an advanced age; and, according to the seventeenth-century chronicler ʿAbd al-Ḥaqq Dihlawī (d. 1642), the mystic actually took two wives, one of whom was the daughter of a local Hindu raja.[2] Having three sons—Abū Saʿīd, Fak̲h̲r al-Dīn and Ḥusām al-Dīn by name—and one daughter named Bībī Jamāl,[2] it so happened that only the latter inherited her father's mystic leanings,[2] whence she too was later venerated as a saint in local Sunni tradition.[2] After settling in Ajmer, Muʿīn al-Dīn worked at firmly establishing the Chishti order of Sunni mysticism in India, and many later biographic accounts relate the numerous miracles wrought by God at the hands of the saint during this period.[2]

Preaching in India

Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī was not the originator or founder of the Chishtiyya order of mysticism as he is often erroneously thought to be. On the contrary, the Chishtiyya was already an established Sufi order prior to his birth, being originally an offshoot of the older Adhamiyya order that traced its spiritual lineage and titular name to the early Islamic saint and mystic Ibrahim ibn Adham (d. 782). Thus, this particular branch of the Adhamiyya was renamed the Chishtiyya after the 10th-century Sunni mystic Abū Isḥāq al-Shāmī (d. 942) migrated to Chishti Sharif, a town in the present-day Herat Province of Afghanistan in around 930, in order to preach Islam in that area. The order spread into the Indian subcontinent, however, at the hands of the Persian Muʿīn al-Dīn in the 13th-century,[7] after the saint is believed to have had a dream in which the Prophet Muhammad appeared and told him to be his "representative" or "envoy" in India.[16][17][18]

According to the various chronicles, Muʿīn al-Dīn's tolerant and compassionate behavior towards the local population seems to have been one of the major reasons behind conversion to Islam at his hand.[19][20] Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī is said to have appointed Bakhtiar Kaki (d. 1235) as his spiritual successor, who worked at spreading the Chishtiyya in Delhi. Furthermore, Muʿīn al-Dīn's son, Fakhr al-Dīn (d. 1255), is said to have further spread the order's teachings in Ajmer, whilst another of the saint's major disciples, Ḥamīd al-Dīn Ṣūfī Nāgawrī (d. 1274), preached in Nagaur, Rajasthan.[7]

Spiritual lineage

As with every other major Sufi order, the Chishtiyya proposes an unbroken spiritual chain of transmitted knowledge going back to the Islamic prophet Muhammad through one of his Companions, which in the Chishtiyya's case is Ali (d. 661).[7] Thus, Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī's spiritual lineage is traditionally given as follows:

- Muhammad.[7]

- ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib (d. 661),

- Ḥasan al-Baṣrī (d. 728),

- Abdul Wahid bin Zaid (d. 786),

- al-Fuḍayl b. ʿIyāḍ (d. 803),

- Ibrahim ibn Adham al-Balkhī (d. 783),

- Ḥudhayfa al-Marʿashī (d. 890),

- Abu Hubayra al-Basri (d. 900),

- Khwaja Mumshad Uluw Al Dīnawarī (d. 911),

- Abu Ishaq Shami (d. 941),

- Abu Aḥmad Abdal Chishti (d. 966),

- Abu Muḥammad Chishti (d. 1020),

- Abu Yusuf ibn Saman Muḥammad Samʿān Chishtī (d. 1067),

- Maudood Chishti (d. 1133),

- Shareef Zandani (d. 1215),

- Usman Harooni (d. 1220),

- Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī,

Dargah Sharif

The tomb (dargāh) of Muʿīn al-Dīn became a deeply venerated site in the century following the preacher's death in March 1236. Honoured by members of all social classes, the tomb was treated with great respect by many of the era's most important Sunni rulers, including Muhammad bin Tughluq, the Sultan of Delhi from 1324-1351, who paid a famous visit to the tomb in 1332 to commemorate the memory of the saint.[21] In a similar way, the later Mughal emperor Akbar (d. 1605) visited the shrine no less than fourteen times during his reign.[22] In the present day, the tomb of Muʿīn al-Dīn continues to be one of the most popular sites of religious visitation for Sunni Muslims in the Indian subcontinent,[6] with over "hundreds of thousands of people from all over the Indian sub-continent assembling there on the occasion of [the saint's] ʿurs or death anniversary."[2] Additionally, the site also attracts many Hindus, who have also venerated the Islamic saint since the medieval period.[2] A bomb blast on October 11, 2007 in the Dargah of Sufi Saint Khawaja Moinuddin Chishti at the time of Roza Iftaar had left three pilgrims dead and 15 injured. A special National Investigation Agency (NIA) court in Jaipur punished with life imprisonment the two convicts in the 2007 Ajmer Dargah bomb blast case.[23]

Popular culture

A song in the 2008 film Jodhaa Akbar named "Khwaja Mere Khwaja," composed by A. R. Rahman, pays tribute to Muʿīn al-Dīn Chishtī.[24][25]

Various qawalis have been portrayed ample of melodies and famous Qawalas including Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan Sahab's Khwaja E khwajgan and The Sabri Brothers Khawaja Ki Deewani.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moinuddin Chishti. |

References

- Oxford Islamic Studies. Oxford Islamic Studies http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e430. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Nizami, K.A., “Čis̲h̲tī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.

- Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield, Telling and Texts: Music, Literature, and Performance in North India (Open Book Publishers, 2015), p. 463

- Arya, Gholam-Ali and Negahban, Farzin, “Chishtiyya”, in: Encyclopaedia Islamica, Editors-in-Chief: Wilferd Madelung and, Farhad Daftary: "The followers of the Chishtiyya Order, which has the largest following among Sufi orders in the Indian subcontinent, are Ḥanafī Sunni Muslims."

- Ḥamīd al-Dīn Nāgawrī, Surūr al-ṣudūr; cited in Auer, Blain, “Chishtī Muʿīn al-Dīn Ḥasan”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson.

- Blain Auer, “Chishtī Muʿīn al-Dīn Ḥasan”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson.

- Arya, Gholam-Ali; Negahban, Farzin. "Chishtiyya". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica.

- See Andrew Rippin (ed.), The Blackwell Companion to the Quran (John Wiley & Sons, 2008), p. 357.

- M. Ali Khan and S. Ram, Encyclopaedia of Sufism: Chisti Order of Sufism and Miscellaneous Literature (Anmol, 2003), p. 34.

- John Esposito (ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Islam (Oxford, 2004), p. 53

- Nizamuddin Auliya (31 December 1996). Fawa'id al-Fu'aad: Spirtual and Literal Discourses. Translated by Z. H. Faruqi. D.K. Print World Ltd. ISBN 9788124600429.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Muhammad bin Mubarak Kirmani. Siyar-ul-Auliya: History of Chishti Silsila (in Urdu). Translated by Ghulam Ahmed Biryan. Lahore: Mushtaq Book Corner.

- Hussain, Zahid (22 April 2012). "Is it permissible to listen to Qawwali?". TheSunniWay. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Muḥammad b. Mubārak Kirmānī, Siyar al-awliyāʾ, Lahore 1978, pp. 54-58.

- Shah Baba, Nawab Gudri, Muinul Arwahʾ (2009)

- ʿAlawī Kirmānī, Muḥammad, Siyar al-awliyāʾ, ed. Iʿjāz al-Ḥaqq Quddūsī (Lahore, 1986), p. 55

- Firishtah, Muḥammad Qāsim, Tārīkh (Kanpur, 1301/1884), 2/377

- Dārā Shukūh, Muḥammad, Safīnat al-awliyāʾ (Kanpur, 1884), p. 93.

- Rizvi, Athar Abbas, A History of Sufism in India (New Delhi, 1986), I/pp. 116-125

- Nizami, Khaliq Ahmad, ‘Ṣūfī Movement in the Deccan’, in H. K. Shervani, ed., A History of Medieval Deccan, vol. 2 (Hyderabad, 1974), pp. 142-147.

- ʿAbd al-Malik ʿIṣāmī, Futūḥ al-salāṭīn, ed. A. S. Usha, Madras 1948, p. 466.

- Abū l-Faḍl, Akbar-nāma, ed. ʿAbd al-Raḥīm, 3 vols., Calcutta 1873–87.

- https://m.timesofindia.com/india/life-sentence-to-two-in-ajmer-dargah-blast-case/articleshow/57773081.cms

- "Jodhaa Akbar Music Review". Planet Bollywood. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "Khwaja Mere Khwaja". Lyrics Translate. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Moinuddin Chishti |