Implicit and explicit atheism

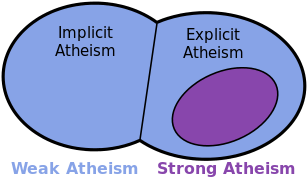

Implicit atheism and explicit atheism are types of atheism.[1] In George H. Smith's Atheism: The Case Against God, "implicit atheism" is defined as "the absence of theistic belief without a conscious rejection of it", while "explicit atheism" is "the absence of theistic belief due to a conscious rejection of it".[1] Explicit atheists have considered the idea of deities and have rejected belief that any exist. Implicit atheists, though they do not themselves maintain a belief in a god or gods, have not rejected the notion or have not considered it further.

| on right | Explicit "positive" / "strong" / "hard" atheists assert that "At least one deity exists" is false. | |

| on right | Explicit "negative" / "weak" / "soft" assert that "At least one deity exists necessarily" is false, without asserting the above. | |

| on left | Implicit "negative" / "weak" / "soft" atheists include agnostics (and infants or babies) who do not believe or do not know whether a deity or deities exist and who have not explicitly rejected or eschewed such a belief. |

| Part of a series on |

| Atheism |

|---|

|

Arguments for atheism |

|

People

|

|

Related stances |

|

Implicit atheism

"Implicit atheism" is "the absence of theistic belief without a conscious rejection of it". "Absence of theistic belief" encompasses all forms of non-belief in deities. This would categorize as implicit atheists those adults who have never heard of the concept of deities, and those adults who have not given the idea any real consideration. Also included are agnostics who assert they do not believe in any deities (even if they claim not to be atheists), and children. As far back as 1772, Baron d'Holbach said that "All children are born Atheists; they have no idea of God".[2] Smith is silent on newborn children, but clearly identifies as atheists some children who are unaware of any concept of any deity:

The man who is unacquainted with theism is an atheist because he does not believe in a god. This category would also include the child with the conceptual capacity to grasp the issues involved, but who is still unaware of those issues. The fact that this child does not believe in god qualifies him as an atheist.[1]

Explicit atheism

Smith observes that some motivations for explicit atheism are rational and some not. Of the rational motivations, he says:

The most significant variety of atheism is explicit atheism of a philosophical nature. This atheism contends that the belief in god is irrational and should therefore be rejected. Since this version of explicit atheism rests on a criticism of theistic beliefs, it is best described as critical atheism.[1]

For Smith, critical, explicit atheism is subdivided further into three groups:[1] p.17

- the view usually expressed by the statement "I do not believe in the existence of a god or supernatural being" after "the failure of theism to provide sufficient evidence in its favor. Faced with a lack of evidence, this explicit atheist sees no reason whatsoever for believing in a supernatural being";

- the view usually expressed by the statement "God does not exist" or "the existence of God is impossible" after "a particular concept of god, such as the God of Christianity, is judged to be absurd or contradictory";

- the view which "refuses to discuss the existence or nonexistence of a god" because "the concept of a 'god' is unintelligible".

For the purposes of his paper on "philosophical atheism", Ernest Nagel chose to attach only the explicit atheism definition for his examination and discussion:

I must begin by stating what sense I am attaching to the word "atheism," and how I am construing the theme of this paper. I shall understand by "atheism" a critique and a denial of the major claims of all varieties of theism. [...] atheism is not to be identified with sheer unbelief, or with disbelief in some particular creed of a religious group. Thus, a child who has received no religious instruction and has never heard about God, is not an atheist – for he is not denying any theistic claims. Similarly in the case of an adult who, if he has withdrawn from the faith of his father without reflection or because of frank indifference to any theological issue, is also not an atheist – for such an adult is not challenging theism and not professing any views on the subject. [...] I propose to examine some philosophic concepts of atheism...[3]

In Nagel's Philosophical Concepts of Atheism, he very much agrees with Smith on the three-part subdivision of "explicit atheism" above, though Nagel does not use the term "explicit".

Other typologies of atheism

The specific narrow focus on positive atheism taken by some professional philosophers like Nagel on the one hand, compared with the scholarship on traditional negative atheism of freethinkers like d'Holbach and Smith on the other has been attributed to the different concerns of professional philosophers and layman proponents of atheism,

"If so many atheists and some of their critics have insisted on the negative definition of atheism, why have some modern philosophers called for a positive definition of atheism -- atheism as the outright denial of God's existence? Part of the reason, I suspect, lies in the chasm separating freethinkers and academic philosophers. Most modern philosophers are totally unfamiliar with atheistic literature and so remain oblivious to the tradition of negative atheism contained in that literature. (see Smith (1990, Chapter 3, p. 51-60[4]))

Everitt (2004) makes the point that professional philosophers are more interested in the grounds for giving or withholding assent to propositions:

We need to distinguish between a biographical or sociological enquiry into why some people have believed or disbelieved in God, and an epistemological enquiry into whether there are any good reasons for either belief or unbelief... We are interested in the question of what good reasons there are for or against God's existence, and no light is thrown on that question by discovering people who hold their beliefs without having good reasons for them.[5]

So, sometimes in philosophy (Flew, Martin and Nagel notwithstanding), only the explicit "denial of theistic belief" is examined, rather than the broader, implicit subject of atheism.

The terms "weak atheism" and "strong atheism", also known as "negative atheism" and "positive atheism", are usually used by Smith as synonyms of the less well-known "implicit" and "explicit" categories. "Strong explicit" atheists assert that it is false that any deities exist. "Weak explicit" atheists assert they do not believe in deities, and do not assert it is true that deities do not exist. Those who do not believe any deities exist, and do not assert their non-belief are included among implicit atheists. Among weak implicit atheists are included the following: children and adults who have never heard of deities; people who have heard of deities but have never given the idea any considerable thought; and those agnostics who suspend belief about deities, but do not reject such belief.[1]

See also

Further reading

References

- Smith, George H. (1979). Atheism: The Case Against God. Buffalo, New York: Prometheus. pp. 13–18. ISBN 0-87975-124-X. Archived from the original on 2020-01-05. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- d'Holbach, P. H. T. (1772). Good Sense. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- Nagel, Ernest (1959). "Philosophical Concepts of Atheism". Basic Beliefs: The Religious Philosophies of Mankind. Sheridan House.

reprinted in Critiques of God, edited by Peter A. Angeles, Prometheus Books, 1997. - Smith, George H. (1990). Atheism, Ayn Rand, and Other Heresies. pp. 51–60. Archived from the original on 2008-07-13.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Everitt, Nicholas, The Non-existence of God: An Introduction. London: Routledge, 2004 (ISBN 0-415-30107-6), p. 10.