Satanism

Satanism is a group of ideological and philosophical beliefs based on Satan. Contemporary religious practice of Satanism began with the founding of the Church of Satan in 1966, although a few historical precedents exist. Prior to the public practice, Satanism existed primarily as an accusation by various Christian groups toward perceived ideological opponents, rather than a self-identity. Satanism, and the concept of Satan, has also been used by artists and entertainers for symbolic expression.

Accusations that various groups have been practicing Satanism have been made throughout much of Christian history. During the Middle Ages, the Inquisition attached to the Catholic Church alleged that various heretical Christian sects and groups, such as the Knights Templar and the Cathars, performed secret Satanic rituals. In the subsequent Early Modern period, belief in a widespread Satanic conspiracy of witches resulted in mass trials of alleged witches across Europe and the North American colonies. Accusations that Satanic conspiracies were active, and behind events such as Protestantism (and conversely, the Protestant claim that the Pope was the Antichrist) and the French Revolution continued to be made in Christendom during the eighteenth to the twentieth century. The idea of a vast Satanic conspiracy reached new heights with the influential Taxil hoax of France in the 1890s, which claimed that Freemasonry worshipped Satan, Lucifer, and Baphomet in their rituals. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Satanic ritual abuse hysteria spread through the United States and the United Kingdom, amid fears that groups of Satanists were regularly sexually abusing and murdering children in their rites. In most of these cases, there is no corroborating evidence that any of those accused of Satanism were actually practitioners of a Satanic religion or guilty of the allegations leveled at them.

Since the 19th century, various small religious groups have emerged that identify as Satanists or use Satanic iconography. Satanist groups that appeared after the 1960s are widely diverse, but two major trends are theistic Satanism and atheistic Satanism. Theistic Satanists venerate Satan as a supernatural deity, viewing him not as omnipotent but rather as a patriarch. In contrast, atheistic Satanists regard Satan as merely a symbol of certain human traits.[1]

Contemporary religious Satanism is predominantly an American phenomenon, the ideas spreading elsewhere with the effects of globalization and the Internet.[2] The Internet spreads awareness of other Satanists, and is also the main battleground for Satanist disputes.[2] Satanism started to reach Central and Eastern Europe in the 1990s, in time with the fall of the Soviet Union, and most noticeably in Poland and Lithuania, predominantly Roman Catholic countries.[3][4]

Definition

In their study of Satanism, the religious studies scholars Asbjørn Dyrendal, James R. Lewis, and Jesper Aa. Petersen stated that the term Satanism "has a history of being a designation made by people against those whom they dislike; it is a term used for 'othering'".[5] The concept of Satanism is an invention of Christianity, for it relies upon the figure of Satan, a character deriving from Christian mythology.[6]

Elsewhere, Petersen noted that "Satanism as something others do is very different from Satanism as a self-designation".[7] Eugene Gallagher noted that, as commonly used, Satanism was usually "a polemical, not a descriptive term".[8]

In 1994, the Italian sociologist Massimo Introvigne suggested defining Satanism with the simultaneous presence of "1) the worship of the character identified with the name of Satan or Lucifer in the Bible, 2) by organized groups with at least a minimal organization and hierarchy, 3) through ritual or liturgical practices." The definition applies regardless the way in which "each group perceives Satan, as personal or impersonal, real or symbolical.[9]

Etymology

The word "Satan" was not originally a proper name but rather an ordinary noun meaning "the adversary"; in this context, it appears at several points in the Old Testament.[10] For instance, in the Book of Samuel, David is presented as the satan ("adversary") of the Philistines, while in the Book of Numbers the term appears as a verb, when God sent an angel to satan ("to oppose") Balaam.[11] Prior to the composition of the New Testament, the idea developed within Jewish communities that Satan was the name of an angel who had rebelled against God and had been cast out of Heaven along with his followers; this account would be incorporated into contemporary texts like the Book of Enoch.[12] This Satan was then featured in parts of the New Testament, where he was presented as a figure who tempted humans to commit sin; in the Book of Matthew and the Book of Luke, he attempted to tempt Jesus of Nazareth as the latter fasted in the wilderness.[13]

The word "Satanism" was adopted into English from the French satanisme.[14] The terms "Satanism" and "Satanist" are first recorded as appearing in the English and French languages during the sixteenth century, when they were used by Christian groups to attack other, rival Christian groups.[15] In a Roman Catholic tract of 1565, the author condemns the "heresies, blasphemies, and sathanismes [sic]" of the Protestants.[14] In an Anglican work of 1559, Anabaptists and other Protestant sects are condemned as "swarmes of Satanistes [sic]".[14] As used in this manner, the term "Satanism" was not used to claim that people literally worshipped Satan, but rather presented the view that through deviating from what the speaker or writer regarded as the true variant of Christianity, they were regarded as being essentially in league with the devil. [16] During the nineteenth century, the term "Satanism" began to be used to describe those considered to lead a broadly immoral lifestyle,[16] and it was only in the late nineteenth century that it came to be applied in English to individuals who were believed to consciously and deliberately venerate Satan.[16] This latter meaning had appeared earlier in the Swedish language; the Lutheran Bishop Laurentius Paulinus Gothus had described devil-worshipping sorcerers as Sathanister in his Ethica Christiana, produced between 1615 and 1630.[17]

Antagonism towards Satanism

Historical and anthropological research suggests that nearly all societies have developed the idea of a sinister and anti-human force that can hide itself within society.[18] This commonly involves a belief in witches, a group of individuals who invert the norms of their society and seek to harm their community, for instance by engaging in incest, murder, and cannibalism.[19] Allegations of witchcraft may have different causes and serve different functions within a society.[20] For instance, they may serve to uphold social norms,[21] to heighten the tension in existing conflicts between individuals,[21] or to scapegoat certain individuals for various social problems.[20]

Another contributing factor to the idea of Satanism is the concept that there is an agent of misfortune and evil who operates on a cosmic scale,[22] something usually associated with a strong form of ethical dualism that divides the world clearly into forces of good and forces of evil.[23] The earliest such entity known is Angra Mainyu, a figure that appears in the Persian religion of Zoroastrianism.[24] This concept was also embraced by Judaism and early Christianity, and although it was soon marginalized within Jewish thought, it gained increasing importance within early Christian understandings of the cosmos.[25] While the early Christian idea of the Devil was not well developed, it gradually adapted and expanded through the creation of folklore, art, theological treatises, and morality tales, thus providing the character with a range of extra-Biblical associations.[26]

Medieval and Early Modern Christendom

As Christianity expanded throughout the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe, it came into contact with a variety of other religions, which it regarded as "pagan". Christian theologians claimed that the gods and goddesses venerated by these "pagans" were not genuine divinities, but were actually demons.[27] However, they did not believe that "pagans" were deliberately devil-worshippers, instead claiming that they were simply misguided.[28] In Christian iconography, the Devil and demons were given the physical traits of figures from Classical mythology such as the god Pan, fauns, and satyrs.[28]

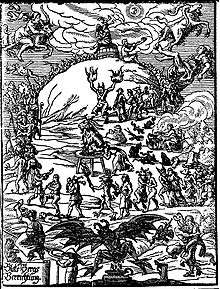

Those Christian groups regarded as heretics by the Roman Catholic Church were treated differently, with theologians arguing that they were deliberately worshipping the Devil.[29] This was accompanied by claims that such individuals engaged in incestuous sexual orgies, murdered infants, and committed acts of cannibalism, all stock accusations that had previously been leveled at Christians themselves in the Roman Empire.[30] The first recorded example of such an accusation being made within Western Christianity took place in Toulouse in 1022, when two clerics were tried for allegedly venerating a demon.[31] Throughout the Middle Ages, this accusation would be applied to a wide range of Christian heretical groups, including the Paulicians, Bogomils, Cathars, Waldensians, and the Hussites.[32] The Knights Templar were accused of worshipping an idol known as Baphomet, with Lucifer having appeared at their meetings in the form of a cat.[33] As well as these Christian groups, these claims were also made about Europe's Jewish community.[34] In the thirteenth century, there were also references made to a group of "Luciferians" led by a woman named Lucardis which hoped to see Satan rule in Heaven. References to this group continued into the fourteenth century, although historians studying the allegations concur that these Luciferians were likely a fictitious invention.[35]

Within Christian thought, the idea developed that certain individuals could make a pact with Satan.[36] This may have emerged after observing that pacts with gods and goddesses played a role in various pre-Christian belief systems, or that such pacts were also made as part of the Christian cult of saints.[37] Another possibility is that it derives from a misunderstanding of Augustine of Hippo's condemnation of augury in his On the Christian Doctrine, written in the late fourth century. Here, he stated that people who consulted augurs were entering "quasi pacts" (covenants) with demons.[38] The idea of the diabolical pact made with demons was popularized across Europe in the story of Faust, likely based in part on the real life Johann Georg Faust.[39]

As the late medieval gave way to the early modern period, European Christendom experienced a schism between the established Roman Catholic Church and the breakaway Protestant movement. In the ensuing Reformation and Counter-Reformation, both Catholics and Protestants accused each other of deliberately being in league with Satan.[40] It was in this context that the terms "Satanist" and "Satanism" emerged.[15]

The early modern period also saw fear of Satanists reach its "historical apogee" in the form of the witch trials of the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries.[41] This came about as the accusations which had been leveled at medieval heretics, among them that of devil-worship, were applied to the pre-existing idea of the witch, or practitioner of malevolent magic.[42] The idea of a conspiracy of Satanic witches was developed by educated elites, although the concept of malevolent witchcraft was a widespread part of popular belief and folkloric ideas about the night witch, the wild hunt, and the dance of the fairies were incorporated into it.[43] The earliest trials took place in Northern Italy and France, before spreading it out to other areas of Europe and to Britain's North American colonies, being carried out by the legal authorities in both Catholic and Protestant regions.[41] Between 30,000 and 50,000 individuals were executed as accused Satanic witches.[41] Most historians agree that the majority of those persecuted in these witch trials were innocent of any involvement in Devil worship.[44] However, in their summary of the evidence for the trials, the historians Geoffrey Scarre and John Callow thought it "without doubt" that some of those accused in the trials had been guilty of employing magic in an attempt to harm their enemies, and were thus genuinely guilty of witchcraft.[45]

In seventeenth-century Sweden, a number of highway robbers and other outlaws living in the forests informed judges that they venerated Satan because he provided more practical assistance than God.[46] The historian of religion Massimo Introvigne regarded these practices as "folkloric Satanism".[17]

18th to 20th century Christendom

During the eighteenth century, gentleman's social clubs became increasingly prominent in Britain and Ireland, among the most secretive of which were the Hellfire Clubs, which were first reported in the 1720s.[47] The most famous of these groups was the Order of the Knights of Saints Francis, which was founded circa 1750 by the aristocrat Sir Francis Dashwood and which assembled first at his estate at West Wycombe and later in Medmenham Abbey.[48] A number of contemporary press sources portrayed these as gatherings of atheist rakes where Christianity was mocked and toasts were made to the Devil.[49] Beyond these sensationalist accounts, which may not be accurate portrayals of actual events, little is known about the activities of the Hellfire Clubs.[49] Introvigne suggested that they may have engaged in a form of "playful Satanism" in which Satan was invoked "to show a daring contempt for conventional morality" by individuals who neither believed in his literal existence nor wanted to pay homage to him.[50]

The French Revolution of 1789 dealt a blow to the hegemony of the Roman Catholic Church in parts of Europe, and soon a number of Catholic authors began making claims that it had been masterminded by a conspiratorial group of Satanists.[51] Among the first to do so was French Catholic priest Jean-Baptiste Fiard, who publicly claimed that a wide range of individuals, from the Jacobins to tarot card readers, were part of a Satanic conspiracy.[52] Fiard's ideas were furthered by Alexis-Vincent-Charles Berbiguier, who devoted a lengthy book to this conspiracy theory; he claimed that Satanists had supernatural powers allowing them to curse people and to shapeshift into both cats and fleas.[53] Although most of his contemporaries regarded Berbiguier as mad,[54] his ideas gained credence among many occultists, including Stanislas de Guaita, a Cabalist who used them for the basis of his book, The Temple of Satan.[55]

In the early 20th century, the British novelist Dennis Wheatley produced a range of influential novels in which his protagonists battled Satanic groups.[56] At the same time, non-fiction authors like Montague Summers and Rollo Ahmed published books claiming that Satanic groups practicing black magic were still active across the world, although they provided no evidence that this was the case.[57] During the 1950s, various British tabloid newspapers repeated such claims, largely basing their accounts on the allegations of one woman, Sarah Jackson, who claimed to have been a member of such a group.[58] In 1973, the British Christian Doreen Irvine published From Witchcraft to Christ, in which she claimed to have been a member of a Satanic group that gave her supernatural powers, such as the ability to levitate, before she escaped and embraced Christianity.[59] In the United States during the 1960s and 1970s, various Christian preachers—the most famous being Mike Warnke in his 1972 book The Satan-Seller—claimed that they had been members of Satanic groups who carried out sex rituals and animal sacrifices before discovering Christianity.[60] According to Gareth Medway in his historical examination of Satanism, these stories were "a series of inventions by insecure people and hack writers, each one based on a previous story, exaggerated a little more each time".[61]

Other publications made allegations of Satanism against historical figures. The 1970s saw the publication of the Romanian Protestant preacher Richard Wurmbrand's book in which he argued—without corroborating evidence—that the socio-political theorist Karl Marx had been a Satanist.[62]

Satanic ritual abuse hysteria

At the end of the twentieth century, a moral panic developed around claims regarding a Devil-worshipping cult that made use of sexual abuse, murder, and cannibalism in its rituals, with children being among its victims.[63] Initially, the alleged perpetrators of such crimes were labeled "witches", although the term "Satanist" was soon adopted as a favored alternative,[63] and the phenomenon itself came to be called "the Satanism Scare".[64] Promoters of the claims alleged that there was a conspiracy of organized Satanists who occupied prominent positions throughout society, from the police to politicians, and that they had been powerful enough to cover up their crimes.[65]

Sociologist of religion Massimo Introvigne, 2016[66]

One of the primary sources for the scare was Michelle Remembers, a 1980 book by the Canadian psychiatrist Lawrence Pazder in which he detailed what he claimed were the repressed memories of his patient (and wife) Michelle Smith. Smith had claimed that as a child she had been abused by her family in Satanic rituals in which babies were sacrificed and Satan himself appeared.[67] In 1983, allegations were made that the McMartin family—owners of a preschool in California—were guilty of sexually abusing the children in their care during Satanic rituals. The allegations resulted in a lengthy and expensive trial, in which all of the accused would eventually be cleared.[68] The publicity generated by the case resulted in similar allegations being made in various other parts of the United States.[69]

A prominent aspect of the Satanic Scare was the claim by those in the developing "anti-Satanism" movement that any child's claim about Satanic ritual abuse must be true, because children would not lie.[70] Although some involved in the anti-Satanism movement were from Jewish and secular backgrounds,[71] a central part was played by fundamentalist and evangelical forms of Christianity, in particular Pentecostalism, with Christian groups holding conferences and producing books and videotapes to promote belief in the conspiracy.[64] Various figures in law enforcement also came to be promoters of the conspiracy theory, with such "cult cops" holding various conferences to promote it.[72] The scare was later imported to the United Kingdom through visiting evangelicals and became popular among some of the country's social workers,[73] resulting in a range of accusations and trials across Britain.[74]

The Satanic ritual abuse hysteria died down between 1990 and 1994.[66] In the late 1980s, the Satanic Scare had lost its impetus following increasing skepticism about such allegations,[75] and a number of those who had been convicted of perpetrating Satanic ritual abuse saw their convictions overturned.[76] In 1990, an agent of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Ken Lanning, revealed that he had investigated 300 allegations of Satanic ritual abuse and found no evidence for Satanism or ritualistic activity in any of them.[76] In the UK, the Department of Health commissioned the anthropologist Jean La Fontaine to examine the allegations of SRA.[77] She noted that while approximately half did reveal evidence of genuine sexual abuse of children, none revealed any evidence that Satanist groups had been involved or that any murders had taken place.[78] She noted three examples in which lone individuals engaged in child molestation had created a ritual performance to facilitate their sexual acts, with the intent of frightening their victims and justifying their actions, but that none of these child molesters were involved in wider Satanist groups.[79] By the 21st century, hysteria about Satanism has waned in most Western countries, although allegations of Satanic ritual abuse continued to surface in parts of continental Europe and Latin America.[80]

Artistic Satanism

Literary Satanism

From the late seventeenth through to the nineteenth century, the character of Satan was increasingly rendered unimportant in Western philosophy and ignored in Christian theology, while in folklore he came to be seen as a foolish rather than a menacing figure.[81] The development of new values in the Age of Enlightenment—in particular those of reason and individualism—contributed to a shift in how many Europeans viewed Satan.[81] In this context, a number of individuals took Satan out of the traditional Christian narrative and reread and reinterpreted him in light of their own time and their own interests, in turn generating new and different portraits of Satan.[82]

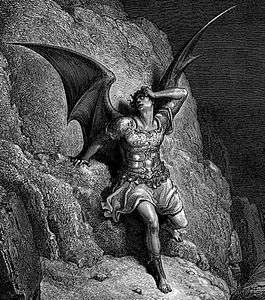

The shifting view of Satan owes many of its origins to John Milton's epic poem Paradise Lost (1667), in which Satan features as the protagonist.[83] Milton was a Puritan and had never intended for his depiction of Satan to be a sympathetic one.[84] However, in portraying Satan as a victim of his own pride who rebeled against God he humanized him and also allowed him to be interpreted as a rebel against tyranny.[85] This was how Milton's Satan was understood by later readers like the publisher Joseph Johnson,[86] and the anarchist philosopher William Godwin, who reflected it in his 1793 book Enquiry Concerning Political Justice.[85] Paradise Lost gained a wide readership in the eighteenth century, both in Britain and in continental Europe, where it had been translated into French by Voltaire.[87] Milton thus became "a central character in rewriting Satanism" and would be viewed by many later religious Satanists as a "de facto Satanist".[82]

The nineteenth century saw the emergence of what has been termed "literary Satanism" or "romantic Satanism".[88] According to Van Luijk, this cannot be seen as a "coherent movement with a single voice, but rather as a post factum identified group of sometimes widely divergent authors among whom a similar theme is found".[89] For the literary Satanists, Satan was depicted as a benevolent and sometimes heroic figure,[90] with these more sympathetic portrayals proliferating in the art and poetry of many romanticist and decadent figures.[82] For these individuals, Satanism was not a religious belief or ritual activity, but rather a "strategic use of a symbol and a character as part of artistic and political expression".[91]

Among the romanticist poets to adopt this view of Satan was the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who had been influenced by Milton.[92] In his poem Laon and Cythna, Shelley praised the "Serpent", a reference to Satan, as a force for good in the universe.[93] Another was Shelley's fellow British poet Lord Byron, who included Satanic themes in his 1821 play Cain, which was a dramatization of the Biblical story of Cain and Abel.[88] These more positive portrayals also developed in France; one example was the 1823 work Eloa by Alfred de Vigny.[94] Satan was also adopted by the French poet Victor Hugo, who made the character's fall from Heaven a central aspect of his La Fin de Satan, in which he outlined his own cosmogony.[95] Although the likes of Shelley and Byron promoted a positive image of Satan in their work, there is no evidence that any of them performed religious rites to venerate him, and thus it is problematic to regard them as religious Satanists.[89]

Radical left-wing political ideas had been spread by the American Revolution of 1765–83 and the French Revolution of 1789–99, and the figure of Satan, who was interpreted as having rebelled against the tyranny imposed by God, was an appealing one for many of the radical leftists of the period.[96] For them, Satan was "a symbol for the struggle against tyranny, injustice, and oppression... a mythical figure of rebellion for an age of revolutions, a larger-than-life individual for an age of individualism, a free thinker in an age struggling for free thought".[91] The French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who was a staunch critic of Christianity, embraced Satan as a symbol of liberty in several of his writings.[97] Another prominent 19th century anarchist, the Russian Mikhail Bakunin, similarly described the figure of Satan as "the eternal rebel, the first freethinker and the emancipator of worlds" in his book God and the State.[98] These ideas likely inspired the American feminist activist Moses Harman to name his anarchist periodical Lucifer the Lightbearer.[99] The idea of this "Leftist Satan" declined during the twentieth century,[99] although it was used on occasion by authorities within the Soviet Union, who portrayed Satan as a symbol of freedom and equality.[100]

Metal and rock music

During the 1960s and 1970s, several rock bands—namely the American Coven and the British Black Widow—employed the imagery of Satanism and witchcraft in their work.[101] References to Satan also appeared in the work of those rock bands which were pioneering the heavy metal genre in Britain during the 1970s.[102] Black Sabbath for instance made mention of Satan in their lyrics, although several of the band's members were practicing Christians and other lyrics affirmed the power of the Christian God over Satan.[103] In the 1980s, greater use of Satanic imagery was made by heavy metal bands like Slayer, Kreator, Sodom, and Destruction.[104] Bands active in the subgenre of death metal—among them Deicide, Morbid Angel, and Entombed—also adopted Satanic imagery, combining it with other morbid and dark imagery, such as that of zombies and serial killers.[105]

Satanism would come to be more closely associated with the subgenre of black metal,[102] in which it was foregrounded over the other themes that had been used in death metal.[106] A number of black metal performers incorporated self-injury into their act, framing this as a manifestation of Satanic devotion.[106] The first black metal band, Venom, proclaimed themselves to be Satanists, although this was more an act of provocation than an expression of genuine devotion to the Devil.[107] Satanic themes were also used by the black metal bands Bathory and Hellhammer.[108] However, the first black metal act to more seriously adopt Satanism was Mercyful Fate, whose vocalist, King Diamond, joined the Church of Satan.[109] More often than not musicians associating themselves with black metal say they do not believe in legitimate Satanic ideology and often profess to being atheists, agnostics, or religious skeptics.[110]

In contrast to King Diamond, various black metal Satanists sought to distance themselves from LaVeyan Satanism, for instance by referring to their beliefs as "devil worship".[111] These individuals regarded Satan as a literal entity,[112] and in contrast to LaVey's views, they associated Satanism with criminality, suicide, and terror.[111] For them, Christianity was regarded as a plague which required eradication.[113] Many of these individuals—such as Varg Vikernes and Euronymous—were Norwegian,[114] and influenced by the strong anti-Christian views of this milieu, between 1992 and 1996 around fifty Norwegian churches were destroyed in arson attacks.[115] Within the black metal scene, a number of musicians later replaced Satanic themes with those deriving from Heathenry, a form of modern Paganism.[116]

Religious Satanism

Religious Satanism does not exist in a single form, as there are multiple different religious Satanisms, each with different ideas about what being a Satanist entails.[117] The historian of religion Ruben van Luijk used a "working definition" in which Satanism was regarded as "the intentional, religiously motivated veneration of Satan".[16]

Dyrendal, Lewis, and Petersen believed that it was not a single movement, but rather a milieu.[118] They and others have nevertheless referred to it as a new religious movement.[119] They believed that there was a family resemblance that united all of the varying groups in this milieu,[5] and that most of them were self religions.[118] They argued that there were a set of features that were common to the groups in this Satanic milieu: these were the positive use of the term "Satanist" as a designation, an emphasis on individualism, a genealogy that connects them to other Satanic groups, a transgressive and antinomian stance, a self-perception as an elite, and an embrace of values such as pride, self-reliance, and productive non-conformity.[120]

Dyrendal, Lewis, and Petersen argued that the groups within the Satanic milieu could be divided into three groups: reactive Satanists, rationalist Satanists, and esoteric Satanists.[121] They saw reactive Satanism as encompassing "popular Satanism, inverted Christianity, and symbolic rebellion" and noted that it situates itself in opposition to society while at the same time conforming to society's perspective of evil.[121] Rationalist Satanism is used to describe the trend in the Satanic milieu which is atheistic, skeptical, materialistic, and epicurean.[122] Esoteric Satanism instead applied to those forms which are theistic and draw upon ideas from other forms of Western esotericism, Modern Paganism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.[122]

Forerunners and early forms

The first person to promote a Satanic philosophy was the Pole Stanislaw Przybyszewski, who promoted a Social Darwinian ideology.[123]

The use of the term "Lucifer" was also taken up by the French ceremonial magician Eliphas Levi, who has been described as a "Romantic Satanist".[124] During his younger days, Levi used "Lucifer" in much the same manner as the literary romantics.[125] As he moved toward a more politically conservative outlook in later life, he retained the use of the term, but instead applied it as to what he believed was a morally neutral facet of the Absolute.[126]

Levi was not the only occultist who wanted to use the term "Lucifer" without adopting the term "Satan" in a similar way.[125] The early Theosophical Society held to the view that "Lucifer" was a force that aided humanity's awakening to its own spiritual nature.[127] In keeping with this view, the Society began production of a journal titled Lucifer.[128]

"Satan" was also used within the esoteric system propounded by the Danish occultist Carl William Hansen, who used the pen name "Ben Kadosh".[128] Hansen was involved in a variety of esoteric groups, including Martinism, Freemasonry, and the Ordo Templi Orientis, drawing on ideas from various groups to establish his own philosophy.[128] In one pamphlet, he provided a "Luciferian" interpretation of Freemasonry.[129] Kadosh's work left little influence outside of Denmark.[130]

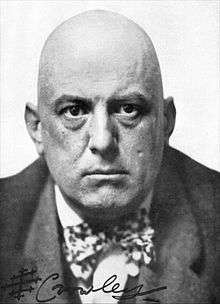

Both during his life and after it, the British occultist Aleister Crowley has been widely described as a Satanist, usually by detractors. Crowley stated he did not consider himself a Satanist, nor did he worship Satan, as he did not accept the Christian world view in which Satan was believed to exist.[131] He nevertheless used imagery considered satanic, for instance by describing himself as "the Beast 666" and referring to the Whore of Babylon in his work, while in later life he sent "Antichristmas cards" to his friends.[132] Dyrendel, Lewis, and Petersen noted that despite the fact that Crowley was not a Satanist, he "in many ways embodies the pre-Satanist esoteric discourse on Satan and Satanism through his lifestyle and his philosophy", with his "image and thought" becoming an "important influence" on the later development of religious Satanism.[129]

In 1928, the Fraternitas Saturni (FS) was established in Germany; its founder, Eugen Grosche, published Satanische Magie ("Satanic Magic") that same year.[133] The group connected Satan to Saturn, claiming that the planet related to the Sun in the same manner that Lucifer relates to the human world.[133]

In 1932, an esoteric group known as the Brotherhood of the Golden Arrow was established in Paris, France by Maria de Naglowska, a Russian occultist who had fled to France following the Russian Revolution.[134] She promoted a theology centered on what she called the Third Term of the Trinity consisting of Father, Son, and Sex, the latter of which she deemed to be most important.[135] Her early disciples, who underwent what she called "Satanic Initiations", included models and art students recruited from bohemian circles.[135] The Golden Arrow disbanded after Naglowska abandoned it in 1936.[136] According to Introvigne, hers was "a quite complicated Satanism, built on a complex philosophical vision of the world, of which little would survive its initiator".[137]

In 1969, a Satanic group based in Toledo, Ohio, part of the United States, came to public attention. Called the Our Lady of Endor Coven, it was led by a man named Herbert Sloane, who described his Satanic tradition as the Ophite Cultus Sathanas and alleged that it had been established in the 1940s.[138] The group offered a Gnostic interpretation of the world in which the creator God was regarded as evil and the Biblical Serpent presented as a force for good who had delivered salvation to humanity in the Garden of Eden.[139] Sloane's claims that his group had a 1940s origin remain unproven; it may be that he falsely claimed older origins for his group to make it appear older than Anton LaVey's Church of Satan, which had been established in 1966.[140]

None of these groups had any real impact on the emergence of the later Satanic milieu in the 1960s.[141]

Rationalistic Satanism

LaVeyan Satanism and the Church of Satan

Anton LaVey, who has been referred to as "The Father of Satanism",[142] synthesized his religion through the establishment of the Church of Satan in 1966 and the publication of The Satanic Bible in 1969. LaVey's teachings promoted "indulgence", "vital existence", "undefiled wisdom", "kindness to those who deserve it", "responsibility to the responsible" and an "eye for an eye" code of ethics, while shunning "abstinence" based on guilt, "spirituality", "unconditional love", "pacifism", "equality", "herd mentality" and "scapegoating". In LaVey's view, the Satanist is a carnal, physical and pragmatic being—and enjoyment of physical existence and an undiluted view of this-worldly truth are promoted as the core values of Satanism, propagating a naturalistic worldview that sees mankind as animals existing in an amoral universe.

LaVey believed that the ideal Satanist should be individualistic and non-conformist, rejecting what he called the "colorless existence" that mainstream society sought to impose on those living within it.[143] He praised the human ego for encouraging an individual's pride, self-respect, and self-realization and accordingly believed in satisfying the ego's desires.[144] He expressed the view that self-indulgence was a desirable trait,[145] and that hate and aggression were not wrong or undesirable emotions but that they were necessary and advantageous for survival.[146] Accordingly, he praised the seven deadly sins as virtues which were beneficial for the individual.[147] The anthropologist Jean La Fontaine highlighted an article that appeared in The Black Flame, in which one writer described "a true Satanic society" as one in which the population consists of "free-spirited, well-armed, fully-conscious, self-disciplined individuals, who will neither need nor tolerate any external entity 'protecting' them or telling them what they can and cannot do."[148]

The sociologist James R. Lewis noted that "LaVey was directly responsible for the genesis of Satanism as a serious religious (as opposed to a purely literary) movement".[149] Scholars agree that there is no reliably documented case of Satanic continuity prior to the founding of the Church of Satan.[150] It was the first organized church in modern times to be devoted to the figure of Satan,[151] and according to Faxneld and Petersen, the Church represented "the first public, highly visible, and long-lasting organization which propounded a coherent satanic discourse".[152] LaVey's book, The Satanic Bible, has been described as the most important document to influence contemporary Satanism.[153] The book contains the core principles of Satanism, and is considered the foundation of its philosophy and dogma.[154] Petersen noted that it is "in many ways the central text of the Satanic milieu",[155] with Lap similarly testifying to its dominant position within the wider Satanic movement.[156] David G. Bromley calls it "iconoclastic" and "the best-known and most influential statement of Satanic theology."[157] Eugene V. Gallagher says that Satanists use LaVey's writings "as lenses through which they view themselves, their group, and the cosmos." He also states: "With a clear-eyed appreciation of true human nature, a love of ritual and pageantry, and a flair for mockery, LaVey's Satanic Bible promulgated a gospel of self-indulgence that, he argued, anyone who dispassionately considered the facts would embrace."[158]

A number of religious studies scholars have described LaVey's Satanism as a form of "self-religion" or "self-spirituality",[159] with religious studies scholar Amina Olander Lap arguing that it should be seen as being both part of the "prosperity wing" of the self-spirituality New Age movement and a form of the Human Potential Movement.[160] The anthropologist Jean La Fontaine described it as having "both elitist and anarchist elements", also citing one occult bookshop owner who referred to the Church's approach as "anarchistic hedonism".[161] In The Invention of Satanism, Dyrendal and Petersen theorized that LaVey viewed his religion as "an antinomian self-religion for productive misfits, with a cynically carnivalesque take on life, and no supernaturalism".[162] The sociologist of religion James R. Lewis even described LaVeyan Satanism as "a blend of Epicureanism and Ayn Rand's philosophy, flavored with a pinch of ritual magic."[163] The historian of religion Mattias Gardell described LaVey's as "a rational ideology of egoistic hedonism and self-preservation",[164] while Nevill Drury characterized LaVeyan Satanism as "a religion of self-indulgence".[165] It has also been described as an "institutionalism of Machiavellian self-interest".[166]

Prominent Church leader Blanche Barton described Satanism as "an alignment, a lifestyle".[167] LaVey and the Church espoused the view that "Satanists are born, not made";[168] that they are outsiders by their nature, living as they see fit,[169] who are self-realized in a religion which appeals to the would-be Satanist's nature, leading them to realize they are Satanists through finding a belief system that is in line with their own perspective and lifestyle.[170] Adherents to the philosophy have described Satanism as a non-spiritual religion of the flesh, or "...the world's first carnal religion".[171] LaVey used Christianity as a negative mirror for his new faith,[172] with LaVeyan Satanism rejecting the basic principles and theology of Christian belief.[161] It views Christianity – alongside other major religions, and philosophies such as humanism and liberal democracy – as a largely negative force on humanity; LaVeyan Satanists perceive Christianity as a lie which promotes idealism, self-denigration, herd behavior, and irrationality.[173] LaVeyans view their religion as a force for redressing this balance by encouraging materialism, egoism, stratification, carnality, atheism, and social Darwinism.[173] LaVey's Satanism was particularly critical of what it understands as Christianity's denial of humanity's animal nature, and it instead calls for the celebration of, and indulgence in, these desires.[161] In doing so, it places an emphasis on the carnal rather than the spiritual.[174]

Practitioners do not believe that Satan literally exists and do not worship him. Instead, Satan is viewed as a positive archetype embracing the Hebrew root of the word "Satan" as "adversary", who represents pride, carnality, and enlightenment, and of a cosmos which Satanists perceive to be motivated by a "dark evolutionary force of entropy that permeates all of nature and provides the drive for survival and propagation inherent in all living things".[175] The Devil is embraced as a symbol of defiance against the Abrahamic faiths which LaVey criticized for what he saw as the suppression of humanity's natural instincts. Moreover, Satan also serves as a metaphorical external projection of the individual's godhood. LaVey espoused the view that "god" is a creation of man, rather than man being a creation of "god". In his book, The Satanic Bible, the Satanist's view of god is described as the Satanist's true "self"—a projection of his or her own personality—not an external deity.[176] Satan is used as a representation of personal liberty and individualism.[177]

LaVey explained that the gods worshipped by other religions are also projections of man's true self. He argues that man's unwillingness to accept his own ego has caused him to externalize these gods so as to avoid the feeling of narcissism that would accompany self-worship.[178] The current High Priest of the Church of Satan, Peter H. Gilmore, further expounds that "...Satan is a symbol of Man living as his prideful, carnal nature dictates [...] Satan is not a conscious entity to be worshipped, rather a reservoir of power inside each human to be tapped at will.[179] The Church of Satan has chosen Satan as its primary symbol because in Hebrew it means adversary, opposer, one to accuse or question. We see ourselves as being these Satans; the adversaries, opposers and accusers of all spiritual belief systems that would try to hamper enjoyment of our life as a human being."[180] The term "Theistic Satanism" has been described as "oxymoronic" by the church and its High Priest.[181] The Church of Satan rejects the legitimacy of any other organizations who claim to be Satanists, dubbing them reverse-Christians, pseudo-Satanists or Devil worshipers, atheistic or otherwise,[182] and maintains a purist approach to Satanism as expounded by LaVey.[151]

First Satanic Church

After LaVey's death in 1997, the Church of Satan was taken over by a new administration and its headquarters were moved to New York. LaVey's daughter, the High Priestess Karla LaVey, felt this to be a disservice to her father's legacy. The First Satanic Church was re-founded on October 31, 1999 by Karla LaVey to carry on the legacy of her father. She continues to run it out of San Francisco, California.

The Satanic Temple

The Satanic Temple is an American religious and political activist organization based in Salem, Massachusetts. The organization actively participates in public affairs that have manifested in several public political actions[183][184] and efforts at lobbying,[185] with a focus on the separation of church and state and using satire against Christian groups that it believes interfere with personal freedom.[185] According to Dyrendal, Lewis, and Petersen, the group were "rationalist, political pranksters".[186] Their pranks are designed to highlight religious hypocrisy and advance the cause of secularism.[187] In one of their actions, they performed a "Pink Mass" over the grave of the mother of the evangelical Christian and prominent anti-LGBT preacher Fred Phelps; the Temple claimed that the mass converted the spirit of Phelps' mother into a lesbian.[186]

The Satanic Temple does not believe in a supernatural Satan, as they believe that this encourages superstition that would keep them from being "malleable to the best current scientific understandings of the material world". The Temple uses the literary Satan as metaphor to construct a cultural narrative which promotes pragmatic skepticism, rational reciprocity, personal autonomy, and curiosity.[188] Satan is thus used as a symbol representing "the eternal rebel" against arbitrary authority and social norms.[189][190]

Theistic Satanism

Theistic Satanism (also known as traditional Satanism, Spiritual Satanism or Devil worship) is a form of Satanism with the primary belief that Satan is an actual deity or force to revere or worship.[191] Other characteristics of theistic Satanism may include a belief in magic, which is manipulated through ritual, although that is not a defining criterion, and theistic Satanists may focus solely on devotion.

Luciferianism

Luciferianism can be understood best as a belief system or intellectual creed that venerates the essential and inherent characteristics that are affixed and commonly given to Lucifer. Luciferianism is often identified as an auxiliary creed or movement of Satanism, due to the common identification of Lucifer with Satan. Some Luciferians accept this identification and/or consider Lucifer as the "light bearer" and illuminated aspect of Satan, giving them the name of Satanists and the right to bear the title. Others reject it, giving the argument that Lucifer is a more positive and easy-going ideal than Satan. They are inspired by the ancient myths of Egypt, Rome and Greece, Gnosticism and traditional Western occultism.

Order of Nine Angles

According to the group's own claims, the Order of Nine Angles was established in Shropshire, Western England during the late 1960s, when a Grand Mistress united a number of ancient pagan groups active in the area.[192] This account states that when the Order's Grand Mistress migrated to Australia, a man known as "Anton Long" took over as the new Grand Master.[192] From 1976 onward he authored an array of texts for the tradition, codifying and extending its teachings, mythos, and structure.[193] Various academics have argued that Long is the pseudonym of British neo-Nazi activist David Myatt,[194] an allegation that Myatt has denied.[195] The ONA arose to public attention in the early 1980s,[196] spreading its message through magazine articles over the following two decades.[197] In 2000, it established a presence on the internet,[197] later adopting social media to promote its message.[198]

The ONA is a secretive organization,[199] and lacks any central administration, instead operating as a network of allied Satanic practitioners, which it terms the "kollective".[200] It consists largely of autonomous cells known as "nexions".[200] The majority of these are located in Britain, Ireland, and Germany, although others are located elsewhere in Europe, and in Russia, Egypt, South Africa, Brazil, Australia, and the United States.[200]

The ONA describe their occultism as "Traditional Satanism".[201] The ONA's writings encourage human sacrifice,[202] referring to their victims as opfers.[203] According to the Order's teachings, such opfers must demonstrate character faults that mark them out as being worthy of death,[204] and accordingly the ONA insists that children must never be victims.[205] No ONA cell have admitted to carrying out a sacrifice in a ritualized manner, but rather Order members have joined the police and military in order to carry out such killings.[206] Faxneld described the Order as "a dangerous and extreme form of Satanism",[207] while religious studies scholar Graham Harvey claimed that the ONA fit the stereotype of the Satanist "better than other groups" by embracing "deeply shocking" and illegal acts.[208]

Temple of Set

The Temple of Set is an initiatory occult society claiming to be the world's leading left-hand path religious organization. It was established in 1975 by Michael A. Aquino and certain members of the priesthood of the Church of Satan,[209] who left because of administrative and philosophical disagreements. ToS deliberately self-differentiates from CoS in several ways, most significantly in theology and sociology.[210] The philosophy of the Temple of Set may be summed up as "enlightened individualism"—enhancement and improvement of oneself by personal education, experiment and initiation. This process is necessarily different and distinctive for each individual. The members do not agree on whether Set is "real" or not, and they're not expected to.[210]

The Temple presents the view that the name Satan was originally a corruption of the name Set.[211] The Temple teaches that Set is a real entity,[212] the only real god in existence, with all others created by the human imagination.[213] Set is described as having given humanity—through the means of non-natural evolution—the "Black Flame" or the "Gift of Set", a questioning intellect which sets the species apart from other animals.[214] While Setians are expected to revere Set, they do not worship him.[215] Central to Setian philosophy is the human individual,[172] with self-deification presented as the ultimate goal.[216]

In 2005 Petersen noted that academic estimates for the Temple's membership varied from between 300 and 500,[217] and Granholm suggested that in 2007 the Temple contained circa 200 members.[218]

Reactive Satanism

Dyrendal, Lewis, and Petersen used the term "reactive Satanism" to describe one form of modern religious Satanism. They described this as an adolescent and anti-social means of rebelling in a Christian society, by which an individual transgresses cultural boundaries.[121] They believed that there were two tendencies within reactive Satanism: one, "Satanic tourism", was characterized by the brief period of time in which an individual was involved, while the other, the "Satanic quest", was typified by a longer and deeper involvement.[122]

The researcher Gareth Medway noted that in 1995 he encountered a British woman who stated that she had been a practicing Satanist during her teenage years. She had grown up in a small mining village, and had come to believe that she had psychic powers. After hearing about Satanism in some library books, she declared herself a Satanist and formulated a belief that Satan was the true god. After her teenage years she abandoned Satanism and became a chaos magickian.[219]

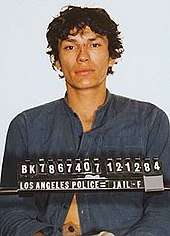

Some reactive Satanists are teenagers or mentally disturbed individuals who have engaged in criminal activities.[220] During the 1980s and 1990s, several groups of teenagers were apprehended after sacrificing animals and vandalizing both churches and graveyards with Satanic imagery.[221] Introvigne expressed the view that these incidents were "more a product of juvenile deviance and marginalization than Satanism".[221] In a few cases the crimes of these reactive Satanists have included murder. In 1970, two separate groups of teenagers—one led by Stanley Baker in Big Sur and the other by Steven Hurd in Los Angeles—killed a total of three people and consumed parts of their corpses in what they later claimed were sacrifices devoted to Satan.[222] In 1984, a U.S. group called the Knights of the Black Circle killed one of its own members, Gary Lauwers, over a disagreement regarding the group's illegal drug dealing; group members later related that Lauwers' death was a sacrifice to Satan.[222] The American serial killer Richard Ramirez for instance claimed that he was a Satanist; during his 1980s killing spree he left an inverted pentagram at the scene of each murder and at his trial called out "Hail Satan!"[223]

Demographics

Dyrendal, Lewis, and Petersen observed that from surveys of Satanists conducted in the early 21st century, it was clear that the Satanic milieu was "heavily dominated by young males".[224] They nevertheless noted that census data from New Zealand suggested that there may be a growing proportion of women becoming Satanists.[224] In comprising more men than women, Satanism differs from most other religious communities, including most new religious communities.[225] Most Satanists came to their religion through reading, either online or books, rather than through being introduced to it through personal contacts.[226] Many practitioners do not claim that they converted to Satanism, but rather state that they were born that way, and only later in life confirmed that Satanism served as an appropriate label for their pre-existing worldviews.[227] Others have stated that they had experiences with supernatural phenomena that led them to embracing Satanism.[228] A number reported feelings of anger in respect of a set of practicing Christians and expressed the view that the monotheistic Gods of Christianity and other religions are unethical, citing issues such as the problem of evil.[229] For some practitioners, Satanism gave a sense of hope, even for those who had been physically and sexually abused.[230]

The surveys revealed that atheistic Satanists appeared to be in the majority, although the numbers of theistic Satanists appeared to grow over time.[231] Beliefs in the afterlife varied, although the most popular afterlife views were reincarnation and the idea that consciousness survives bodily death.[232] The surveys also demonstrated that most recorded Satanists practiced magic,[233] although there were differing opinions as to whether magical acts operated according to etheric laws or whether the effect of magic was purely psychological.[234] A number described performing cursing, in most cases as a form of vigilante justice.[235] Most practitioners conduct their religious observances in a solitary manner, and never or rarely meet fellow Satanists for rituals.[236] Rather, the primary interaction that takes place between Satanists is online, on websites or via email.[237] From their survey data, Dyrendal, Lewis, and Petersen noted that the average length of involvement in the Satanic milieu was seven years.[238] A Satanist's involvement in the movement tends to peak in the early twenties and drops off sharply in their thirties.[239] A small proportion retain their allegiance to the religion into their elder years.[240] When asked about their political views, the largest proportion of Satanists identified as apolitical or non-aligned, while only a small percentage identified as conservative despite the conservative views of prominent Satanists like LaVey and Marilyn Manson.[241] A small minority of Satanists expressed support for the far right; conversely, over two-thirds expressed negative or extremely negative views about Nazism and neo-Nazism.[228]

Legal recognition

In 2004, it was claimed that Satanism was allowed in the Royal Navy of the British Armed Forces, despite opposition from Christians.[242][243][244] In 2016, under a Freedom of Information request, the Navy Command Headquarters stated that "we do not recognise satanism as a formal religion, and will not grant facilities or make specific time available for individual 'worship'."[245]

In 2005, the Supreme Court of the United States debated in the case of Cutter v. Wilkinson over protecting minority religious rights of prison inmates after a lawsuit challenging the issue was filed to them.[246][247] The court ruled that facilities that accept federal funds cannot deny prisoners accommodations that are necessary to engage in activities for the practice of their own religious beliefs.[248][249]

See also

- Contemporary Religious Satanism

- Demonology

- Devil in popular culture

- Satanic ritual abuse

References

Footnotes

- Gilmore, Peter. "Science and Satanism". Point of Inquiry Interview. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- Jesper Aagaard Petersen (2009). "Introduction: Embracing Satan". Contemporary Religious Satanism: A Critical Anthology. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-5286-1.

- Alisauskiene, Milda (2009). "The Peculiarities of Lithuanian Satanism". In Jesper Aagaard Petersen (ed.). Contemporary Religious Satanism: A Critical Anthology. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-5286-1.

- "Satanism stalks Poland". BBC News. 2000-06-05.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 7.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 16.

- Petersen 2012, p. 92.

- Gallagher 2006, p. 151.

- Introvigne, Massimo (September 29, 2016). Satanism: A Social History. Aries Book Series. Leiden ; Boston: Brill. p. 3. ISBN 9789004244962. OCLC 1030572947. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2020 – via archive.is.

- Medway 2001, p. 51; Van Luijk 2016, p. 19.

- Medway 2001, p. 51.

- Medway 2001, p. 52.

- Medway 2001, p. 53.

- Medway 2001, p. 9.

- Medway 2001, p. 257; Van Luijk 2016, p. 2.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 2.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 44.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 13–14.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 14.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 16.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 15.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 19.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 20.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 19; Van Luijk 2016, p. 18.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 21.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 21–22.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 23.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 24.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 24–26.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 25–26.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 25.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 28.

- Medway 2001, p. 126.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 28–29.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 29–31.

- Medway 2001, p. 57.

- Medway 2001, p. 58.

- Medway 2001, pp. 57–58.

- Medway 2001, pp. 60–63.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 35.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 36.

- Medway 2001, p. 133; Van Luijk 2016, p. 37.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 38.

- Medway 2001, p. 70.

- Scarre & Callow 2001, p. 2.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 44–45.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 58–59; Van Luijk 2016, p. 66.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 66–67.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 66.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 60–61.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 71.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 71–73.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 74–78.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 84–85.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 85–86.

- Medway 2001, pp. 266–267.

- Medway 2001, pp. 141–142.

- Medway 2001, pp. 143–149.

- Medway 2001, pp. 159–161.

- Medway 2001, pp. 164–170.

- Medway 2001, p. 161.

- Medway 2001, pp. 262–263; Introvigne 2016, p. 66.

- La Fontaine 2016, p. 13.

- La Fontaine 2016, p. 15.

- La Fontaine 2016, p. 13; Introvigne 2016, p. 381.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 372.

- Medway 2001, pp. 175–177; Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 115–116; Introvigne 2016, pp. 374–376.

- Medway 2001, pp. 178–183; Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 116–120; Introvigne 2016, pp. 405–406.

- Medway 2001, p. 183.

- La Fontaine 2016, p. 16.

- Medway 2001, p. 369; La Fontaine 2016, p. 15.

- Medway 2001, pp. 191–195.

- Medway 2001, pp. 220–221.

- Medway 2001, pp. 234–248.

- Medway 2001, pp. 210–211.

- Medway 2001, p. 213.

- Medway 2001, p. 249.

- La Fontaine 2016, pp. 13–14.

- Medway 2001, p. 118; La Fontaine 2016, p. 14.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 456.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 29.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 28.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 28; Van Luijk 2016, p. 70.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 28, 30.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 30.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 28, 30; Van Luijk 2016, pp. 69–70.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 70.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 73.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 108.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 69.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 31.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 71–72.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 97–98.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 74–75.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 105–107.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 77–79.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 117–119.

- Van Luijk 2016, pp. 119–120.

- Van Luijk 2016, p. 120.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 66.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 462–463.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 467.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 467–468.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 468.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 468–469.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 469.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 470.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 472–473.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 471.

- "Death to False Satanism | NOISEY". NOISEY. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 480.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 479.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 482.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 479–481.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 481.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 503–504.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 3.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 4.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 3; Introvigne 2016, p. 517.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 7–9.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 5.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 6.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 36.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 107.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 37.

- Dyrendal; no 16.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 37–38.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 38.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 39.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 39; Introvigne 2016, p. 227.

- Hutton 1999, p. 175; Dyrendal 2012, pp. 369–370.

- Hutton 1999, p. 175.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 42.

- Medway 2001, p. 18; Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 43–44.

- Medway 2001, p. 18.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 45.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 277.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 49–50; Introvigne 2016, p. 278.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 49–50; Introvigne 2016, p. 280.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 50; Introvigne 2016, p. 278.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 46.

- Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (2009). Contemporary Religious Satanism. ISBN 9780754652861.

- Dyrendal 2013, p. 129.

- Lap 2013, p. 92.

- Maxwell-Stuart 2011, p. 198.

- Lap 2013, p. 94.

- Gardell 2003, p. 288; Schipper 2010, p. 107.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 97.

- Lewis 2001, p. 5.

- Contemporary Esotericism, Asprem & Granholm 2014, p. 75.

- Lewis 2002, p. 5.

- Faxneld & Petersen 2013, p. 81.

- Lewis 2003, p. 116.

- Lewis 2003, p. 105.

- Petersen 2013, p. 232.

- Lap 2013, p. 85.

- Bromley 2005, pp. 8127–8128.

- Gallagher 2005, p. 6530.

- Harvey 1995, p. 290; Partridge 2004, p. 82; Petersen 2009, pp. 224–225; Schipper 2010, p. 108; Faxneld & Petersen 2013, p. 79.

- Lap 2013, p. 84.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 96.

- The Invention of Satanism & Asbjorn Dyrendal, Jesper Aa. Petersen, James R. Lewis 2016, p. 70.

- Lewis 2002, p. 2.

- Gardell 2003, p. 288.

- Drury 2003, p. 188.

- Taub & Nelson 1993, p. 528.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 99.

- Contemporary Religious Satanism: A Critical Anthology & Petersen 2009, p. 9.

- The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity & Faxneld, Petersen 2013, p. 129.

- Satanism Today & Lewis 2001, p. 330.

- Who's? Right: Mankind, Religions & The End Times & Warman-Stallings 2012, p. 35.

- Schipper 2010, p. 109.

- Faxneld & Petersen 2013, p. 80.

- Lewis 2001b, p. 50.

- Controversial New Religions, Lewis & Petersen 2014, p. 408.

- Wright 1993, p. 143.

- Cavaglion & Sela-Shayovitz 2005, p. 255.

- LaVey 2005, pp. 44–45.

- High Priest, Magus Peter H. Gilmore. "Satanism: The Feared Religion". churchofsatan.com.

- The Church of Satan [History Channel]. YouTube. 12 January 2012.

- High Priest, Magus Peter H. Gilmore. "F.A.Q. Fundamental Beliefs". churchofsatan.com.

- Ohlheiser, Abby (7 November 2014). "The Church of Satan wants you to stop calling these 'devil worshiping' alleged murderers Satanists". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- Massoud Hayoun (2013-12-08). "Group aims to put 'Satanist' monument near Oklahoma capitol | Al Jazeera America". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- "Satanists petition to build monument on Oklahoma state capitol grounds | Washington Times Communities". The Washington Times. 2013-12-09. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- Bugbee, Shane (2013-07-30). "Unmasking Lucien Greaves, Leader of the Satanic Temple | VICE United States". Vice.com. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 219.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 220.

- Oppenheimer, Mark (July 10, 2015). "A Mischievous Thorn in the Side of Conservative Christianity". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-07-11.

- "FAQ". The Satanic Temple. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- "What does Satan mean to the Satanic Temple? - CNN". CNN. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- Partridge, Christopher Hugh (2004). The Re-enchantment of the West. p. 82. ISBN 9780567082695. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2003, p. 218; Senholt 2013, p. 256.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2003, p. 218; Senholt 2013, p. 256; Monette 2013, p. 87.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2003, p. 216; Senholt 2013, p. 268; Faxneld 2013a, p. 207.

- Ryan 2003, p. 53; Senholt 2013, p. 267.

- Gardell 2003, p. 293.

- Senholt 2013, p. 256.

- Monette 2013, p. 107.

- Kaplan 2000, p. 236.

- Monette 2013, p. 88.

- Faxneld 2013a, p. 207; Faxneld 2013b, p. 88; Senholt 2013, p. 250; Sieg 2013, p. 252.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2003, pp. 218–219; Baddeley 2010, p. 155.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2003, p. 219.

- Kaplan 2000, p. 237; Ryan 2003, p. 54.

- Harvey 1995, p. 292; Kaplan 2000, p. 237.

- Monette 2013, p. 114.

- Faxneld 2013a, p. 207.

- Harvey 1995, p. 292.

- Aquino, Michael (2002). Church of Satan (PDF). San Francisco: Temple of Set. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-12.

- Harvey, Graham (2009). "Satanism: Performing Alterity and Othering". In Jesper Aagaard Petersen (ed.). Contemporary Religious Satanism: A Critical Anthology. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-5286-1.

- Gardell 2003, p. 390.

- Petersen 2005, p. 436; Harvey 2009, p. 32.

- Granholm 2009, pp. 93–94; Granholm 2013, p. 218.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 102; Gardell 2003, p. 291; Petersen 2005, p. 436.

- Granholm 2009, p. 94.

- Faxneld & Petersen 2013, p. 7.

- Petersen 2005, p. 435.

- Granholm 2009, p. 93; Granholm 2013, p. 223.

- Medway 2001, pp. 362–365.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 130.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 445.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 446.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 122.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 138.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 158.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 146.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 142.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 143.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 202–204.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 200–201.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 179–180.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 181–182.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 183.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 209.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 210–212.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, pp. 151, 153.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 153.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 157.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 159.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 160.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 171.

- Royal Navy to allow devil worship CNN

- Carter, Helen. The devil and the deep blue sea: Navy gives blessing to sailor Satanist. The Guardian

- Navy approves first ever Satanist BBC News

- Ministry of Defence Request for Information. Navy Command FOI Section, 7 January 2016.

- Linda Greenhouse (March 22, 2005). "Inmates Who Follow Satanism and Wicca Find Unlikely Ally". The New York Times.

- "Before high court: law that allows for religious rights". The Christian Science Monitor.

- Johnson, M. Alex (May 31, 2005). "Court upholds prisoners' religious rights". MSNBC. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- "Cutter v. Wilkinson 544 U.S. 709 (2005)". Oyez. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

Sources

- Baddeley, Gavin (2010). Lucifer Rising: Sin, Devil Worship & Rock n' Roll (third ed.). London: Plexus. ISBN 978-0-85965-455-5.

- Dyrendal, Asbjørn (2012). "Satan and the Beast: The Influence of Aleister Crowley on Modern Satanism". In Henrik Bogdan; Martin P. Starr (eds.). Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 369–394. ISBN 978-0-19-986309-9.

- Dyrendal, Asbjørn; Lewis, James R.; Petersen, Jesper Aa. (2016). The Invention of Satanism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195181104.

- Faxneld, Per (2013a). "Post-Satanism, Left-Hand Paths, and Beyond: Visiting the Margins". The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity. Per Faxneld and Jesper Aagaard Petersen (editors). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 205–208. ISBN 978-0-19-977924-6.

- ——— (2013b). "Secret Lineages and De Facto Satanists: Anton LaVey's Use of Esoteric Tradition". Contemporary Esotericism. Egil Asprem and Kennet Granholm (editors). Durham: Acumen. pp. 72–90. ISBN 978-1-317-54357-2.

- Faxneld, Per; Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (2013). "Introduction: At the Devil's Crossroads". In Per Faxneld; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (eds.). The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-0-19-977924-6.

- Gallagher, Eugene (2006). "Satanism and the Church of Satan". Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America. Eugene V. Gallagher, W. Michael Ashcraft (editors). Greenwood. pp. 151–168. ISBN 978-0313050787.

- Gardell, Matthias (2003). Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism. Durham and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3071-4.

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (2003). Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-3155-0.

- Granholm, Kennet (2009). "Embracing Others than Satan: The Multiple Princes of Darkness in the Left-Hand Path Milieu". In Jesper Aagard Petersen (ed.). Contemporary Religious Satanism: A Critical Anthology. Farnham: Ashgate. pp. 85–101. ISBN 978-0-7546-5286-1.

- ——— (2013). "The Left-Hand Path and Post-Satanism: The Temple of Set and the Evolution of Satanism". In Per Faxneld; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (eds.). The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 209–228. ISBN 978-0-19-977924-6.

- Harvey, Graham (1995). "Satanism in Britain Today". Journal of Contemporary Religion. 10 (3): 283–296. doi:10.1080/13537909508580747.

- ——— (2009). "Satanism: Performing Alterity and Othering". In Jesper Aagard Petersen (ed.). Contemporary Religious Satanism: A Critical Anthology. Farnham: Ashgate. pp. 27–40. ISBN 978-0-7546-5286-1.

- Hutton, Ronald (1999). The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1928-5449-0.

- Introvigne, Massimo (2016). Satanism: A Social History. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9004288287.

- Kaplan, Jeffrey (2000). "Order of Nine Angles". Encyclopedia of White Power: A Sourcebook on the Radical Racist Right. Jeffrey Kaplan (editor). Lanham: AltaMira Press. pp. 235–238. ISBN 978-0-7425-0340-3.

- La Fontaine, Jean (1999). "Satanism and Satanic Mythology". In Bengt Ankarloo; Stuart Clark (eds.). The Athlone History of Witchcraft and Magic in Europe. 6: The Twentieth Century. London: Athlone. pp. 94–140. ISBN 0-485-89006-2.

- La Fontaine, Jean (2016). Witches and Demons: A Comparative Perspective on Witchcraft and Satanism. New York and Oxford: Berhahn. ISBN 978-1-78533-085-8.

- Medway, Gareth J. (2001). Lure of the Sinister: The Unnatural History of Satanism. New York and London: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814756454.

- Monette, Connell (2013). Mysticism in the 21st Century. Wilsonville, Oregon: Sirius Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-940964-00-3.

- Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (2005). "Modern Satanism: Dark Doctrines and Black Flames". In James R. Lewis; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (eds.). Controversial New Religions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 423–457. ISBN 978-0-19-515683-6.

- Ryan, Nick (2003). Homeland: Into a World of Hate. Edinburgh and London: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84018-465-5.

- Scarre, Geoffrey; Callow, John (2001). Witchcraft and Magic in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Europe (second ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave. ISBN 9780333920824.

- Schipper, Bernd U. (2010). "From Milton to Modern Satanism: The History of the Devil and the Dynamics between Religion and Literature". Journal of Religion in Europe. 3 (1): 103–124. doi:10.1163/187489210X12597396698744.

- Senholt, Jacob C. (2013). "Secret Identities in the Sinister Tradition: Political Esotericism and the Convergence of Radical Islam, Satanism, and National Socialism in the Order of Nine Angles". The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity. Per Faxneld and Jesper Aagaard Petersen (editors). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 250–274. ISBN 978-0-19-977924-6.

- Sieg, George (2013). "Angular Momentum: From Traditional to Progressive Satanism in the Order of Nine Angles". International Journal for the Study of New Religions. 4 (2): 251–283. doi:10.1558/ijsnr.v4i2.251.

- Van Luijk, Ruben (2016). Children of Lucifer: The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190275105.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Satanism. |