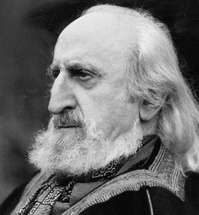

Frithjof Schuon

Frithjof Schuon (/ˈʃuːɒn/; German: [ˈfʀiːtˌjoːf ˈʃuː.ɔn]; 18 June, 1907 – 5 May, 1998), also known as ʿĪsā Nūr ad-Dīn ʾAḥmad (Arabic: عيسیٰ نور الـدّين أحمد) after his conversion to Islam,[1] was an author of German ancestry born in Basel, Switzerland. Schuon is widely recognized as one of the most influential scholars and teachers within the sphere of comparative religion whose religious worldview was influenced by his study of the Hindu philosophy of Advaita Vedanta and Islamic Sufism. He authored numerous books on religion and spirituality as well as being a poet and a painter.

Frithjof Schuon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 18, 1907 |

| Died | May 5, 1998 (aged 90) Bloomington, Indiana, U.S. |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | |

| School | Perennial philosophy |

Main interests | Philosophy, metaphysics, spirituality, religion, sacred studies |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

In his prose and poetic writings, Schuon focuses on metaphysical doctrine and spiritual method. He is considered one of the main representatives and exponents of the religio perennis (perennial religion) and one of the chief representatives of the Traditionalist School. In his writings, Schuon expresses his faith in an absolute principle, God, who governs the universe and to whom our souls would return after death. For Schuon, the great revelations are the link between this absolute principle—God—and humankind. He wrote the main bulk of his work in French. In the later years of his life, Schuon composed some volumes of poetry in his mother tongue, German. His articles in French were collected in about 20 titles in French which were later translated into English as well as many other languages. The main subjects of his prose and poetic compositions are spirituality and various essential realms of the human life coming from God and returning to God.[2]

Life and work

Schuon was born in Basel, Switzerland, on June 18, 1907. His father was a native of southern Germany, while his mother came from an Alsatian family. Schuon's father was a concert violinist and the household was one in which not only music but literary and spiritual culture were present. Schuon lived in Basel and attended school there until the untimely death of his father, after which his mother returned with her two young sons to her family in nearby Mulhouse, France, where Schuon was obliged to become a French citizen. Having received his earliest training in German, he received his later education in French and thus mastered both languages early in life.[3]

From his youth, Schuon's search for metaphysical truth led him to read the Hindu scriptures such as Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita. While still living in Mulhouse, he discovered the works of René Guénon, the French philosopher and Orientalist, which served to confirm his intellectual intuitions and which provided support for the metaphysical principles he had begun to discover.[3]

Schuon journeyed to Paris after serving for a year and a half in the French army. There he worked as a textile designer and began to study Arabic in the local mosque school. Living in Paris also brought the opportunity to be exposed to various forms of traditional art to a much greater degree than before, especially the arts of Asia with which he had had a deep affinity since his youth. This period of growing intellectual and artistic familiarity with the traditional worlds was followed by Schuon's first visit to Algeria in 1932. It was then that he met the celebrated Shaykh Ahmad al-Alawi and was initiated into his order.[4] Schuon has written about his deep affinity with the esoteric core of various traditions and hence appreciation for the Sufism in the Islamic tradition. His main reason for seeking the blessings of Shaykh Al-Alawi being exactly the attachment to an orthodox master and Saint.[5] On a second trip to North Africa, in 1935, he visited Algeria and Morocco; and during 1938 and 1939 he traveled to Egypt where he met Guénon, with whom he had been in correspondence for 27 years. In 1939, shortly after his arrival in Pie, India, World War II broke out, forcing him to return to Europe. After having served in the French army, and having been made a prisoner by the Germans, he sought asylum in Switzerland, which gave him Swiss nationality and was to be his home for forty years. In 1949 he married, his wife being a German Swiss with a French education who, besides having interests in religion and metaphysics, was also a gifted painter.[3]

Following World War II, Schuon accepted an invitation to travel to the American West, where he lived for several months among the Plains Indians, in whom he always had a deep interest. Having received his education in France, Schuon has written all his major works in French, which began to appear in English translation in 1953. Of his first book, The Transcendent Unity of Religions (London, Faber & Faber) T. S. Eliot wrote: "I have met with no more impressive work in the comparative study of Oriental and Occidental religion."[3]

While always continuing to write, Schuon and his wife traveled widely. In 1959 and again in 1963, they journeyed to the American West at the invitation of friends among the Sioux and Crow American Indians. In the company of their Native American friends, they visited various Plains tribes and had the opportunity to witness many aspects of their sacred traditions. In 1959, Schuon and his wife were solemnly adopted into the Sioux family of James Red Cloud, descendant of Red Cloud. Years later they were similarly adopted by the Crow medicine man and Sun Dance chief, Thomas Yellowtail. Schuon's writings on the central rites of Native American religion and his paintings of their ways of life attest to his particular affinity with the spiritual universe of the Plains Indians. Other travels have included journeys to Andalusia, Morocco, and a visit in 1968 to the reputed home of the Virgin Mary in Ephesus.

Through his many books and articles, Schuon became known as a spiritual teacher and leader of the Traditionalist School. During his years in Switzerland he regularly received visits from well-known religious scholars and thinkers of the East.[3]

Schuon throughout his entire life had great respect for and devotion to the Virgin Mary which was expressed in his writings. As a result, his teachings and paintings show a particular Marian presence. His reverence for the Virgin Mary has been studied in detail by American professor James Cutsinger.[6] Hence the name, Maryamiya (in Arabic, "Marian"), of the Sufi order he founded as a branch of the Shadhiliya-Darqawiya-Alawiya. When asked by one of his disciples about the reason for this choice of name, Schuon replied: "It is not we who have chosen her; it is she who has chosen us."[7]

In 1980, Schuon and his wife emigrated to the United States, settling in Bloomington, Indiana, where a community of disciples from all over the world would gather around him for spiritual direction. The first years in Bloomington saw the publication of some of his most important late works: From the Divine to the Human, To Have a Center, Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism and others.

Schuon was deeply attracted to the Native American traditions. It was American anthropologist Joseph Epes Brown who through letters and journeys to Lausanne would speak of the Native Americans to Schuon and would create possibilities of exchange between Schuon and that world, exchanges that were to play an important role in the last period of the Schuon’s' life. In the autumn of 1953, Schuon and his wife met with Thomas Yellowtail in Paris. The future Sun Dance Chief was making a dance tour. In his autobiography, Schuon explained how, after Yellowtail had performed a special rite, he had a visionary dream revealing to him certain aspects of the Plain Indian symbolism. Thomas Yellowtail remained his intimate friend till his death in 1993, visiting him every year after his settlement in Bloomington. During the visits of Yellowtail, Schuon and some of his followers organized what they called “Indian Days,” involving the performance of Native American dances[8] of which some have accused him of practising ritual nudity apart from regular strictly Islamic Sufi gatherings of invocation (majalis al-dhikr).[9] These gatherings were understood by disciples as a sharing in Schuon's personal insights and realization, not as part of the initiatic method he transmitted, centered on the invocation of a Divine Name.[10]

In 1991, one of Schuon's followers accused him of "fondling" three young girls during “primordial gatherings”. A preliminary investigation was begun, but the chief prosecutor eventually concluded that there was no proof, noting that the plaintiff was of extremely dubious character who had been previously condemned for making false statements in another similar affair in California.[11] The prosecutor declared that there were no grounds for prosecution, and the local press made amends. Some articles and books, including Mark Sedgwick's Against the Modern World,[12] purporting to be scholarly documents,[13] discuss this event and the related "primordial" practices of the Bloomington community in Midwestern suburban America in the late twentieth century.[14] Schuon was greatly affected, but continued to write poetry in his native German, to receive visitors and maintain a busy correspondence with followers, scholars and readers until his death in 1998.[3][15]

Views based on his written works

Transcendent unity of religions

The traditionalist or perennialist perspective began to be enunciated in the 1920s by the French philosopher René Guénon and, in the 1930s, by Schuon himself. Orientalist Ananda Coomaraswamy and Swiss art historian Titus Burckhardt also became prominent advocates of this point of view. Fundamentally, this doctrine is the Sanatana Dharma – the "eternal religion" – of Hindu Neo-Vedanta. It was supposedly formulated in ancient Greece, in particular, by Plato and later Neoplatonists, and in Christendom by Meister Eckhart (in the West) and Gregory Palamas (in the East). Every religion has, besides its literal meaning, an esoteric dimension, which is essential, primordial and universal. This intellectual universality is one of the hallmarks of Schuon's works, and it gives rise to insights into not only the various spiritual traditions, but also history, science and art.[16]

The dominant theme or principle of Schuon's writings was foreshadowed in his early encounter with a Black marabout who had accompanied some members of his Senegalese village to Switzerland in order to demonstrate their culture. When the young Schuon talked with him, the venerable old man drew a circle with radii on the ground and explained: God is in the center; all paths lead to Him.[17]

Metaphysics

For Schuon, the quintessence of pure metaphysics can be summarized by the following vedantic statement, although the Advaita Vedanta's perspective finds its equivalent in the teachings of Ibn Arabi, Meister Eckhart or Plotinus: Brahma satyam jagan mithya jivo brahmaiva na'parah (Brahman is real, the world is illusory, the self is not different from Brahman).[18]

The metaphysics exposited by Schuon is based on the doctrine of the non-dual Absolute (Beyond-Being) and the degrees of reality. The distinction between the Absolute and the relative corresponds for Schuon to the couple Atma/Maya. Maya is not only the cosmic illusion: from a higher standpoint, Maya is also the Infinite, the Divine Relativity or else the feminine aspect (mahashakti) of the Supreme Principle.

Said differently, being the Absolute, Beyond-Being is also the Sovereign Good (Agathon), that by its nature desires to communicate itself through the projection of Maya. The whole manifestation from the first Being (Ishvara) to matter (Prakriti), the lower degree of reality, is indeed the projection of the Supreme Principle (Brahman). The personal God, considered as the creative cause of the world, is only relatively Absolute, a first determination of Beyond-Being, at the summit of Maya. The Supreme Principle is not only Beyond-Being. It is also the Supreme Self (Atman) and in its innermost essence, the Intellect (buddhi) that is the ray of Consciousness shining down, the axial refraction of Atma within Maya.[19]

Spiritual path

According to Schuon the spiritual path is essentially based on the discernment between the "Real" and the "unreal" (Atma / Maya); concentration on the Real; and the practice of virtues. Human beings must know the "Truth". Knowing the Truth, they must then will the "Good" and concentrate on it. These two aspects correspond to the metaphysical doctrine and the spiritual method. Knowing the Truth and willing the Good, human beings must finally love "Beauty" in their own soul through virtue, but also in "Nature". In this respect Schuon has insisted on the importance for the authentic spiritual seeker to be aware of what he called the "metaphysical transparency of phenomena".[20]

Schuon wrote about different aspects of spiritual life both on the doctrinal and on the practical levels. He explained the forms of the spiritual practices as they have been manifested in various traditional universes. In particular, he wrote on the Invocation of the Divine Name (dhikr, Japa-Yoga, the Prayer of the Heart), considered by Hindus as the best and most providential means of realization at the end of the Kali Yuga. As has been noted by the Hindu saint Ramakrishna, the secret of the invocatory path is that God and his Name are one.[21]

Schuon's views are in harmony with traditional Islamic teachings of the primacy of "Remembrance of God" as emphasized by Shaykh Al-Alawi in the following passage:

Remembrance (dhikr) is the most important rule of the religion. The law was not imposed upon us nor the rites of worship ordained except for the sake of establishing the remembrance of God (dhikru ʾLlāh). The Prophet said: ‘The circumambulation (ṭawāf) around the Holy House, the passage to and fro between (the hills of) Safa and Marwa, and the throwing of the pebbles (on three pillars symbolizing the devil) were ordained only for the sake of the Remembrance of God.’ And God Himself has said (in the Koran): ‘Remember God at the Holy Monument.’ Thus we know that the rite that consists in stopping there was ordained for remembrance and not specifically for the sake of the monument itself, just as the halt at Muna was ordained for remembrance and not because of the valley. Furthermore He (God) has said on the subject of the ritual prayer: ‘Perform the prayer in remembrance of Me.’ In a word, our performance of the rites is considered ardent or lukewarm according to the degree of our remembrance of God while performing them. Thus when the Prophet was asked which spiritual strivers would receive the greatest reward, he replied: ‘Those who have remembered God most.’ And when asked which fasters would receive the greatest reward, he replied: ‘Those who have remembered God most.’ And when the prayer and the almsgiving and the pilgrimage and the charitable donations were mentioned, he said each time: ‘The richest in remembrance of God is the richest in reward.’[22]

Quintessential esoterism

Guénon had pointed out at the beginning of the twentieth century that every religion comprises two main aspects, "esoterism" and "exoterism". Schuon explained that esoterism displays two aspects, one being an extension of exoterism and the other one independent of exoterism; for if it be true that the form "is" in a certain way the essence, the essence on the contrary is by no means totally expressed by a single form; the drop is water, but water is not the drop. This second aspect is called "quintessential esoterism" for it is not limited or expressed totally by one single form or theological school and, above all, by a particular religious form as such.[23]

Criticism of modernity

Guénon had based his Crisis of the Modern World on the Hindu doctrine of cyclic nature of time.[24] Schuon expanded on this concept and its consequences for humanity in many of his articles.[25] In his essay "The Contradictions of Relativism", Schuon wrote that the uncompromising relativism that underlies many modern philosophies had fallen into an intrinsic absurdity in declaring that there is no absolute truth and then attempting to put this forward as an absolute truth. Schuon notes that the essence of relativism is found in the idea that we never escape from human subjectivity whilst its expounders seem to remain unaware of the fact that relativism is therefore also deprived of any objectivity. Schuon further notes that the Freudian assertion that rationality is merely a hypocritical guise for a repressed animal drive results in the very assertion itself being devoid of worth as it is itself a rational judgment.[26][27]

Works

Books in English

- Adastra and Stella Maris: Poems by Frithjof Schuon, World Wisdom, 2003

- Autumn Leaves & The Ring: Poems by Frithjof Schuon, World Wisdom, 2010

- Castes and Races, Perennial Books, 1959, 1982

- Christianity/Islam, World Wisdom, 1985

- New translation, World Wisdom, 2008

- Dimensions of Islam, 1969

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom, World Wisdom, 1992

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way, Perennial Books, 1981, 1990

- The Eye of the Heart, World Wisdom, 1997

- The Feathered Sun: Plain Indians in Art & Philosophy, World Wisdom, 1990

- Form and Substance in the Religions, World Wisdom, 2002

- From the Divine to the Human, World Wisdom, 1982

- New translation, World Wisdom, 2013

- Gnosis: Divine Wisdom, 1959, 1978, Perennial Books 1990

- New translation, World Wisdom, 2006

- Images of Primordial & Mystic Beauty: Paintings by Frithjof Schuon, Abodes, 1992, World Wisdom

- In the Face of the Absolute, World Wisdom, 1989, 1994

- In the Tracks of Buddhism, 1968, 1989

- New translation, Treasures of Buddhism, World Wisdom, 1993

- Islam and the Perennial Philosophy, Scorpion Cavendish, 1976

- Language of the Self, 1959

- Revised edition, World Wisdom, 1999

- Light on the Ancient Worlds, 1966, World Wisdom, 1984

- New translation, World Wisdom, 2006

- Logic and Transcendence, 1975, Perennial Books, 1984

- New translation, World Wisdom, 2009

- The Play of Masks, World Wisdom, 1992

- Primordial Meditation: Contemplating the Real, The Matheson Trust, 2015 (translated from the original German)

- Road to the Heart, World Wisdom, 1995

- Roots of the Human Condition, World Wisdom, 1991

- New translation, World Wisdom, 2002

- Songs Without Names Vol. I-VI, World Wisdom, 2007

- Songs Without Names VII-XII, World Wisdom, 2007

- Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts, 1954, 1969

- New translation, World Wisdom, 2008

- Stations of Wisdom, 1961, 1980

- Revised translation, World Wisdom, 1995, 2003

- Sufism: Veil and Quintessence, World Wisdom, 1981, 2007

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism, World Wisdom, 1986, 2000

- The Transcendent Unity of Religions, 1953

- Revised Edition, 1975, 1984, The Theosophical Publishing House, 1993

- The Transfiguration of Man, World Wisdom, 1995

- Treasures of Buddhism ( = In the Tracks of Buddhism) (1968, 1989, 1993)

- To Have a Center, World Wisdom, 1990, 2015

- Understanding Islam, 1963, 1965, 1972, 1976, 1979, 1981, 1986, 1989

- Revised translation, World Wisdom, Foreword by Annemarie Schimmel, 1994, 1998, 2011

- World Wheel Vol. I-III, World Wisdom, 2007

- World Wheel Vol. IV-VII, World Wisdom, 2007

Schuon was a frequent contributor to the quarterly journal Studies in Comparative Religion, (along with Guénon, Coomarswamy, and many others) which dealt with religious symbolism and the Traditionalist perspective.[28]

Bibliography

- Art from the Sacred to the Profane: East and West, (A selection from his writings by Catherine Schuon), World Wisdom, Inc, 2007. ISBN 1933316357

- The Essential Frithjof Schuon, World Wisdom, 2005

- The Essential Writings of Frithjof Schuon, ed. Seyyed Hossein Nasr, 1986, Element, 1991

- The Fullness of God: Frithjof Schuon on Christianity, Foreword by Antoine Faivre ed. James Cutsinger (2004)

- Prayer Fashions Man: Frithjof Schuon on the Spiritual Life, ed. James Cutsinger (2005)

- René Guénon: Some Observations, ed. William Stoddart (2004)

- Songs for a Spiritual Traveler: Selected Poems, World Wisdom, 2002

- American Gurus: From American Transcendentalism to New Age Religion, Arthur Versluis (2014), Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199368136

- Harry Oldmeadow (2010). Frithjof Schuon and the Perennial Philosophy. World Wisdom. ISBN 9781935493099.

- Splendor of the true : a Frithjof Schuon reader, James S. Cutsinger, State University of New York Press, 2013. ISBN 9781438446127.[29]

- Frithjof Schuon and Sri Ramana Maharshi: A survey of the spiritual masters of the 20th century, Mateus Soares de Azevedo, Sacred Web, a Journal of Tradition and Modernity, volume 10, 2002. [30]

See also

References

- Vincent Cornell, Voices of Islam: Voices of the spirit, Greenwood Publishing Group (2007), p. xxvi.

- Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. p. 1. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

- Frithjof Schuon's life and work.

- Frithjof Schuon, Songs Without Names, Volumes VII-XII, (World Wisdom, 2007) p. 226.

- J. B. Aymard and Patrick Laude. Frithjof Schuon, life and teachings. SUNY press 2002

- "Colorless Light and Pure Air: The Virgin in the Thought of Frithjof Schuon" for some reflections, and J.-B. Aymard’s "Approche biographique" for chronological details.

- Martin Lings, A Return to the Spirit, Fons Vitae, Kentucky, 2005, p. 6.

- Renaud Fabbri, Frithjof Schuon: The Shining Realm of the Pure Intellect (MA diss., Miami University, 2007), 30.

- American Gurus: From Transcendentalism to New Age Religion, Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 170. by Arthur Versluis.

- Aymard and Laude, Frithjof Schuon: Life and Teachings, SUNY Press, NY, 2004.

- Renaud Fabbri, Frithjof Schuon: The Shining Realm of the Pure Intellect, 47.

- Mark Segdwick (2004). Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century. Oxford Scholarship Online. p. 171ff. doi:10.1093/0195152972.001.0001. ISBN 9780195152975.

- Book critique by Horváth, Róbert and reviews by Fitzgerald, Michael Oren and Poindexter, Wilson Eliot (2009). "Articles". studiesincomparativereligion.com. Retrieved 2018-08-23.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Versluis, Arthur (2014). American Gurus: From Transcendentalism to New Age Religion. Oxford university press. ISBN 9780199368143.

- J.-B. Aymard, "Approche biographique", in Connaissance des Religions, Numéro Hors Série Frithjof Schuon, 1999, Coédition Connaissance des Religions/ Le Courrier du Livre.

- Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. pp. i. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

- Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. pp. Backcover. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

- Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. p. 21. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

- Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. p. 37. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

- Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. p. 61. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

- Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. USA: World Wisdom Books. p. 73. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

- (Shaykh Aḥmad al-ʿAlawī in his treatise Al-Qawl al-Maʿrūf)

- Schuon, Frithjof (1982). From the Divine to the Human. US: World Wisdom Books. p. 85. ISBN 0-941532-01-1.

- The System of Antichrist: Truth and Falsehood in Postmodernism and the New Age, Chapter: The Prophecy of René Guénon, By Charles Upton, Sophia Perennis, 2005 - 88 pages, Pages 8 to 10

- Nasr, Critic of the modern World, pages 46 à 50 , in The Essential Frithjof Schuon,

- Logic and transcendence, Perennial Books, 1975.

- A Mística Islâmica em Terræ Brasilis: o Sufismo e as Ordens Sufis em São Paulo Archived 2015-04-14 at the Wayback Machine. Mário Alves da Silva Filho. Dissertação apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo em 2012. (in Portuguese)

- Journal of American Society of Philosophy

- World Catalog

- Sacred Web

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Frithjof Schuon |

- Perennialist/Traditionalist School website

- Schuon website

- Fons Vitae books - Traditionalist School books

- Frithjof Schuon Archive

- World Wisdom - Perennial Philosophy

- Frithjof Schuon metaphysician, theologian and philosopher

- Frithjof Schuon Swiss metaphysician, theologian and philosopher Oxford University Press

- Publications by and about Frithjof Schuon in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library