Intercession of saints

Intercession of the saints is a doctrine held by the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Roman Catholic Churches. The practice of praying through saints can be found in Christian writings from the 3rd century onward.[2][3] The 4th-century Apostles' Creed states belief in the communion of saints, which certain Christian churches interpret as supporting the intercession of saints. As in Christianity, this practice is controversial in Judaism and Islam.

Biblical basis

Intercession of the dead for the living

On the basis of the intercession for believers by Christ, who is present at the right hand of God (Romans 8:34; Hebrews 7:25), it is argued by extension that other people who have died but are alive in Christ might be able to intercede on behalf of the petitioner (John 11:21-25; Romans 8:38–39).

Aquinas quotes Revelation 8:4: "And the smoke of the incense of the prayers of the saints ascended up before God from the hand of the angel."[4]

Both those for and against the intercession of saints quote Job 5:1.

Jesus' parable of the rich man and Lazarus in Luke 16:19–31 indicates the ability of the dead to pray for the living.[5] The intercession of the dead for the living is shown in 2 Maccabees 15:14–17; an intercession on behalf of Israel by the late high priest Onias III plus that of Jeremiah, the prophet who died almost 400 years earlier. "And Onias spoke, saying, 'This is a man who loves the brethren and prays much for the people and the holy city, Jeremiah, the prophet of God.'"

Intercession of the living for the living

According to the Epistle to the Romans, the living can intercede for the living:

"Now I (Paul) beseech you, brethren, for the Lord Jesus Christ's sake, and for the love of the Spirit, that ye strive together with me in your prayers to God for me" (Romans 15:30).

Mary intercedes at the wedding at Cana and occasions Jesus's first miracle. "On the third day a wedding took place at Cana in Galilee. Jesus’ mother was there, and Jesus and his disciples had also been invited to the wedding. When the wine was gone, Jesus’ mother said to him, 'They have no more wine.' 'Woman, why do you involve me?' Jesus replied. 'My hour has not yet come.' His mother said to the servants, 'Do whatever he tells you'” (John 2:1-5).[6]

When God was displeased by the four men who had attempted to give advice to the patriarch Job, he said to them, "My servant Job will pray for you, and I will accept his prayer and not deal with you according to your folly" (Job 42:8).[7]

Moses says to God, "'Forgive the sin of these people, just as you have pardoned them from the time they left Egypt until now.' The Lord replied, 'I have forgiven them, as you asked'" (Numbers 14:19-20).

The elders of the church can intercede for the sick people. "Is anyone among you sick? Let them call the elders of the church to pray over them and anoint them with oil in the name of the Lord. And the prayer offered in faith will make the sick person well; the Lord will raise them up. If they have sinned, they will be forgiven" (James 5:14-15).

Intercession of the living for the dead

Intercession of the living for the dead is allegedly seen in 2 Timothy 1:16–18. "The Lord give mercy unto the house of Onesiphorus; for he oft refreshed me, and was not ashamed of my chain: But, when he was in Rome, he sought me out very diligently, and found me. The Lord grant unto him that he may find mercy of the Lord in that day: and in how many things he ministered unto me at Ephesus, thou knowest very well."[8]

Catholic view

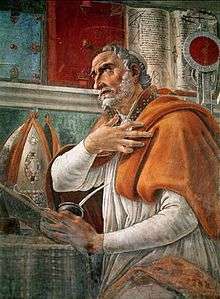

Roman Catholic Church doctrine supports intercessory prayer to saints. Intercessory prayer to saints also plays an important role in the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches. In addition, some Anglo-Catholics believe in saintly intercession. This practice is an application of the Catholic doctrine of the Communion of Saints. Some of the early basis for this was the belief that martyrs passed immediately into the presence of God and could obtain graces and blessings for others. A further reinforcement was derived from the cult of the angels which, while pre-Christian in its origin, was heartily embraced by the faithful of the sub-Apostolic age.[9]

According to St. Jerome, "If the Apostles and Martyrs, while still in the body, can pray for others, at a time when they must still be anxious for themselves, how much more after their crowns, victories, and triumphs are won!"[4]

The Catholic doctrine of intercession and invocation is set forth by the Council of Trent, which teaches that "...the saints who reign together with Christ offer up their own prayers to God for men. It is good and useful suppliantly to invoke them, and to have recourse to their prayers, aid, and help for obtaining benefits from God, through His Son Jesus Christ our Lord, Who alone is our Redeemer and Saviour."[4]

Intercessory prayer to saintly persons who have not yet been canonized is also practiced, and evidence of miracles produced as a result of such prayer is very commonly produced during the formal process of beatification and canonization.

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

956 The intercession of the saints. "Being more closely united to Christ, those who dwell in heaven fix the whole Church more firmly in holiness. . . . They do not cease to intercede with the Father for us, as they proffer the merits which they acquired on earth through the one mediator between God and men, Christ Jesus . . . . So by their fraternal concern is our weakness greatly helped."[10]

Some Catholic scholars have reinterpreted invocation and intercession of the saints with a critical view toward the medieval tendencies of imagining the saints in heaven distributing favors to whom they will and instead seeing in proper devotion to the saints a means of response to God’s activity in us through these creative models of Christ-likeness.[11]

Protestant views

With the exception of a few early Protestant churches, most modern Protestant churches strongly reject the intercession of the dead for the living, but they are in favor of the intercession of the living for the living according to Romans 15:30.

Anglican views

The first Anglican articles of faith, the Ten Articles (1536), defended the practice of praying to saints,[12] while the King's Book, the official statement of religion produced in 1543, devotes an entire section to the importance of the Ave Maria ("Hail Mary") prayer.[13] However, the Thirty-nine Articles (1563) condemn "invocation of saints" as "a fond thing, vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God" (Article XXII).[14]

Theologians within the Anglican Communion make a clear distinction between a "Romish" doctrine concerning the invocation of saints and what they view as the "Patristic" doctrine of intercession of the saints, permitting the latter, but forbidding the former.[15] The bishop William Forbes termed the Anglican practice advocation of the saints, meaning "asking for the saints to pray with them and on their behalf, not praying to them".[16]

Lutheran views

The Lutheran confessions approve honoring the saints by thanking God for examples of his mercy, by using the saints as examples for strengthening the believers' faith, and by imitating their faith and other virtues.[18][19][20] However, the confessions strongly reject invoking the saints to ask for their help. The Augsburg Confession emphasizes that Christ is the only mediator between God and man, and that he is the one to whom Christians ought to pray.[lower-alpha 1]

Reformed views

Like Lutherans, strict Calvinists and other Reformed Christians understand the "communion of saints" mentioned in the Apostles' Creed to consist of all believers, including those who have died,[23] but invocation of departed saints is regarded as a transgression of the First Commandment.[24]

Methodist views

Article XIV of the Methodist Articles of Religion from 1784, echoing the Anglican Thirty-nine Articles, rejects invocation of saints by declaring the doctrine "a fond thing, vainly invented, and grounded upon no warrant of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God".[25]

Parallels in other religions

Judaism

There is some evidence of a Jewish belief in intercession, both in the form of the paternal blessings passed down from Abraham to his children, and 2 Maccabees, where Judas Maccabaeus sees the dead Onias and Jeremiah giving blessing to the Jewish army. In ancient Judaism, it was also popular to pray for intercession from Michael in spite of the rabbinical prohibition against appealing to angels as intermediaries between God and his people. There were two prayers written beseeching him as the prince of mercy to intercede in favor of Israel: one composed by Eliezer ha-Kalir, and the other by Judah ben Samuel he-Hasid.[26] Those who oppose this practice feel that to God alone may prayers be offered.

In modern times one of the greatest divisions in Jewish theology (hashkafa) is over the issue of whether one can beseech the help of a tzadik – an extremely righteous individual. The main conflict is over a practice of beseeching a tzadik who has already died to make intercession before the Almighty.[27] This practice is common mainly among Chasidic Jews, but also found in varying degrees among other usually Chareidi communities. It strongest opposition is found largely among sectors of Modern Orthodox Judaism, Dor Daim and Talmide haRambam, and among aspects of the Litvish Chareidi community. Those who oppose this practice usually do so over the problem of idolatry, as Jewish Law strictly prohibits making use of a mediator (melitz) or agent (sarsur) between oneself and the Almighty.

The perspectives of those Jewish groups opposed to the use of intercessors is usually softer in regard to beseeching the Almighty alone merely in the "merit" (tzechut) of a tzadik.

Those Jews who support the use of intercessors claim that their beseeching of the tzadik is not prayer or worship. The conflict between the groups is essentially over what constitutes prayer, worship, a mediator (melitz), and an agent (sarsur).

Islam

Tawassul is the practice of using someone as a means or an intermediary in a supplication directed towards God. An example of this would be such: "O my Lord, help me with [such and such need] due to the love I have for Your Prophet."

Some Shi'a practice seeking intercession from saints, in particular from Muhammad's son-in-law, Ali and Ali's son, Husayn. A well-known Persian Shi'a hymn reads "Z bandegi-ye 'Ali na-ajab bashar be-khoda rasad" ("It is not strange that man, through servitude to 'Ali, will reach God").

Serer religion

In the religion of the Serer people of Senegal, the Gambia and Mauritania, some of their ancient dead are canonized as Holy Saints, called Pangool in the Serer language. These ancient ancestors act as interceders between the living world and their supreme deity Roog.[28]

See also

Notes

- The intercession of saints was criticized in the Augsburg Confession, Article XXI: Of the Worship of the Saints. This criticism was refuted by the Catholic side in the Confutation,[21] which in turn was refuted by the Lutheran side in the Apology to the Augsburg Confession.[22]

References

- On the Birthday of Saint John the Baptist, Sermon 293B:5:1. “Against superstitious midsummer rituals.” Augustine’s Works, Sermons on the Saints, (1994), Sermons 273–305, John E. Rotelle, ed., Edmund Hill, Trans., ISBN 1-56548-060-0 ISBN 978-1-56548-060-5 p. 165. Editor's comment (ibid., note 16, p. 167): “So does ‘his grace’ mean John’s grace? Clearly not in the ordinary understanding of such a phrase, as though John were the source of the grace. But in the sense that John’s grace is the grace of being the friend of the bridegroom, and that that is the grace we are asking him to obtain for us too, yes, it does mean John’s grace.”

- "On the Intercession and Invocation of the Saints". orthodoxinfo.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-06-19. Retrieved 2009-09-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Intercession". newadvent.org.

- "4 Biblical Proofs for Prayers to Saints and for the Dead". National Catholic Register. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John+2%3A1-5&version=NIV

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Job+42%3A8&version=NIV

- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=2+Timothy+1%3A16%E2%80%9318&version=KJV

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary". newadvent.org.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church - The Communion of Saints. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Patricia A. Sullivan. “A Reinterpretation of Invocation and Intercession of the Saints.” Theological Studies 66, no.2 (2005): 381-400. https://theologicalstudies.net/2005-all-volumes-and-table-of-contents/.

- Schofield, John (2006). Philip Melanchthon and the English Reformation, Ashgate Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7546-5567-1

- A Necessary Doctrine and Erudition for Any Christian Man Set forth by the King’s Majesty of England, &c.. (1543)

- Thirty-Nine Articles, Article XXII: "Of Purgatory"

- Sokol, David F. (2001). The Anglican Prayer Life: Ceum Na Corach', the True Way. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-595-19171-0.

In 1556 Article XXII in part read ... 'The Romish doctrine concerning ... invocation of saints, is a fond thing vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the word of God.' The term 'doctrina Romanensium' or Romish doctrine was substituted for the 'doctrina scholasticorum' of the doctrine of the school authors in 1563 to bring the condemnation up to date subsequent to the Council of Trent. As E. J. Bicknell writes, invocation may mean either of two things: the simple request to a saint for his prayers (intercession), 'ora pro nobis', or a request for some particular benefit. In medieval times the saints had come to be regarded as themselves the authors of blessings. Such a view was condemned but the former was affirmed.

- Mitchican, Jonathan A. (26 August 2016). "The Non-Competitive Mary – Working the Beads". Working the Beads. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

The Scottish priest William Forbes (1558–1634) argued that Anglicans could call upon the saints without running afoul of the Articles by simply making it clear, in their minds if nowhere else, that they are asking for the saints to pray with them and on their behalf, not praying to them. Forbes styled this advocation as opposed to invocation.

- Augsburg Confession, Article 21, "Of the Worship of the Saints". trans. Kolb, R., Wengert, T., and Arand, C. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2000.

- Augsburg Confession XXI 1

- Apology of the Augsburg Confession XXI 4–7

- "Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod – Christian Cyclopedia". lcms.org.

- "1530 Roman Confutation". bookofconcord.org.

- Apology to the Augsburg Confession, Article XXI : Of the Invocation of Saints

- Heidelberg Catechism, Question 55

- Heidelberg Catechism, Question 94

- Articles of Religion, Article XIV: "Of Purgatory"

- Baruch Apoc. Ethiopic, ix. 5

- "Is it okay to ask a deceased tzaddik to pray on my behalf?" at Chabad.org

- Gravrand, Henry, "La civilisation sereer", vol. II : Pangool, Nouvelles éditions africaines, Dakar, 1990, pp 305-402

External links

- Church Fathers on the Intercession of the Saints

- Marian Prayers and Prayers of the Saints

- Marian Novenas and Novenas to Saints

- Index and Calendar of Saints

- Salatul Istisqa, Islamic prayer for rain ceremony

- The performance of the Salatul Istisqa, the Islamic prayer for rain, in the parched bed of the Goulburn River in Denman, in the Hunter Valley, Sydney, Australia, 2003.

- Hadith Proofs for Tawassul through the Prophet