Social constructionism

Social constructionism is a theory of knowledge in sociology and communication theory that examines the development of jointly-constructed understandings of the world that form the basis for shared assumptions about reality. The theory centers on the notion that meanings are developed in coordination with others rather than separately within each individual.[1]

Social constructs can be different based on the society and the events surrounding the time period in which they exist.[2] An example of a social construct is money or the concept of currency, as people in society have agreed to give it importance/value.[2][3] Another example of a social construction is the concept of self/self-identity.[4] Charles Cooley stated based on his looking-glass self theory: "I am not who you think I am; I am not who I think I am; I am who I think you think I am."[2] This demonstrates how people in society construct ideas or concepts that may not exist without the existence of people or language to validate those concepts.[2][5]

There are weak and strong social constructs.[3] Weak social constructs rely on brute facts (which are fundamental facts that are difficult to explain or understand, such as quarks) or institutional facts (which are formed from social conventions).[2][3] Strong social constructs rely on the human perspective and knowledge that does not just exist, but is rather constructed by society.[2]

Definition

A social construct or construction concerns the meaning, notion, or connotation placed on an object or event by a society, and adopted by the inhabitants of that society with respect to how they view or deal with the object or event.[6] In that respect, a social construct as an idea would be widely accepted as natural by the society.

A major focus of social constructionism is to uncover the ways in which individuals and groups participate in the construction of their perceived social reality. It involves looking at the ways social phenomena are developed, institutionalized, known, and made into tradition by humans.

Origins

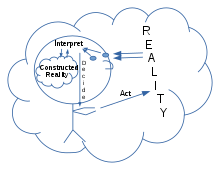

In 1886 or 1887, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote that, “Facts do not exist, only interpretations.” In his 1922 book Public Opinion, Walter Lippmann said, "The real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance" between people and their environment. Each person constructs a pseudo-environment that is a subjective, biased, and necessarily abridged mental image of the world, and to a degree, everyone's pseudo-environment is a fiction. People "live in the same world, but they think and feel in different ones."[7] Lippman's “environment” might be called “reality,” and his “pseudo-environment” seems equivalent to what today is called “constructed reality.”

Social constructionism has more recently been rooted in "symbolic interactionism" and "phenomenology."[8][9] With Berger and Luckmann's The Social Construction of Reality published in 1966, this concept found its hold. More than four decades later, much theory and research pledged itself to the basic tenet that people "make their social and cultural worlds at the same time these worlds make them."[9] It is a viewpoint that uproots social processes "simultaneously playful and serious, by which reality is both revealed and concealed, created and destroyed by our activities."[9] It provides a substitute to the "Western intellectual tradition" where the researcher "earnestly seeks certainty in a representation of reality by means of propositions."[9]

In social constructionist terms, "taken-for-granted realities" are cultivated from "interactions between and among social agents;" furthermore, reality is not some objective truth "waiting to be uncovered through positivist scientific inquiry."[9] Rather, there can be "multiple realities that compete for truth and legitimacy."[9] Social constructionism understands the "fundamental role of language and communication" and this understanding has "contributed to the linguistic turn" and more recently the "turn to discourse theory."[9][10] The majority of social constructionists abide by the belief that "language does not mirror reality; rather, it constitutes [creates] it."[9]

A broad definition of social constructionism has its supporters and critics in the organizational sciences.[9] A constructionist approach to various organizational and managerial phenomena appear to be more commonplace and on the rise.[9]

Andy Lock and Tomj Strong trace some of the fundamental tenets of social constructionism back to the work of the 18th-century Italian political philosopher, rhetorician, historian, and jurist Giambattista Vico.[11]

Berger and Luckmann give credit to Max Scheler as a large influence as he created the idea of Sociology of knowledge which influenced social construction theory.[12]

According to Lock and Strong, other influential thinkers whose work has affected the development of social constructionism are: Edmund Husserl, Alfred Schutz, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Martin Heidegger, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Paul Ricoeur, Jürgen Habermas, Emmanuel Levinas, Mikhail Bakhtin, Valentin Volosinov, Lev Vygotsky, George Herbert Mead, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Gregory Bateson, Harold Garfinkel, Erving Goffman, Anthony Giddens, Michel Foucault, Ken Gergen, Mary Gergen, Rom Harre, and John Shotter.[11]

Applications

Personal construct psychology

Since its appearance in the 1950s, personal construct psychology (PCP) has mainly developed as a constructivist theory of personality and a system of transforming individual meaning-making processes, largely in therapeutic contexts.[13][14][15][16][17][18] It was based around the notion of persons as scientists who form and test theories about their worlds. Therefore, it represented one of the first attempts to appreciate the constructive nature of experience and the meaning persons give to their experience.[19] Social constructionism (SC), on the other hand, mainly developed as a form of a critique,[20] aimed to transform the oppressing effects of the social meaning-making processes. Over the years, it has grown into a cluster of different approaches,[21] with no single SC position.[22] However, different approaches under the generic term of SC are loosely linked by some shared assumptions about language, knowledge, and reality.[23]

A usual way of thinking about the relationship between PCP and SC is treating them as two separate entities that are similar in some aspects, but also very different in others. This way of conceptualizing this relationship is a logical result of the circumstantial differences of their emergence. In subsequent analyses these differences between PCP and SC were framed around several points of tension, formulated as binary oppositions: personal/social; individualist/relational; agency/structure; constructivist/constructionist.[24][25][26][27][28][29] Although some of the most important issues in contemporary psychology are elaborated in these contributions, the polarized positioning also sustained the idea of a separation between PCP and SC, paving the way for only limited opportunities for dialogue between them.[30][31]

Reframing the relationship between PCP and SC may be of use in both the PCP and the SC communities. On one hand, it extends and enriches SC theory and points to benefits of applying the PCP “toolkit” in constructionist therapy and research. On the other hand, the reframing contributes to PCP theory and points to new ways of addressing social construction in therapeutic conversations.[31]

Educational psychology

Like social constructionism, social constructivism states that people work together to construct artifacts. While social constructionism focuses on the artifacts that are created through the social interactions of a group, social constructivism focuses on an individual's learning that takes place because of his or her interactions in a group.

Social constructivism has been studied by many educational psychologists, who are concerned with its implications for teaching and learning. For more on the psychological dimensions of social constructivism, see the work of Ernst von Glasersfeld and A. Sullivan Palincsar.[32]

Systemic therapy

Systemic therapy is a form of psychotherapy which seeks to address people as people in relationship, dealing with the interactions of groups and their interactional patterns and dynamics.

Crime

Potter and Kappeler (1996), in their introduction to Constructing Crime: Perspective on Making News And Social Problems wrote, "Public opinion and crime facts demonstrate no congruence. The reality of crime in the United States has been subverted to a constructed reality as ephemeral as swamp gas."[33]

Communication studies

A bibliographic review of social constructionism as used within communication studies was published in 2016. It features a good overview of resources from that disciplinary perspective.[34]

History and development

Berger and Luckmann

Constructionism became prominent in the U.S. with Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann's 1966 book, The Social Construction of Reality. Berger and Luckmann argue that all knowledge, including the most basic, taken-for-granted common sense knowledge of everyday reality, is derived from and maintained by social interactions. When people interact, they do so with the understanding that their respective perceptions of reality are related, and as they act upon this understanding their common knowledge of reality becomes reinforced. Since this common sense knowledge is negotiated by people, human typifications, significations and institutions come to be presented as part of an objective reality, particularly for future generations who were not involved in the original process of negotiation. For example, as parents negotiate rules for their children to follow, those rules confront the children as externally produced "givens" that they cannot change. Berger and Luckmann's social constructionism has its roots in phenomenology. It links to Heidegger and Edmund Husserl through the teaching of Alfred Schutz, who was also Berger's PhD adviser.

Narrative turn

During the 1970s and 1980s, social constructionist theory underwent a transformation as constructionist sociologists engaged with the work of Michel Foucault and others as a narrative turn in the social sciences was worked out in practice. This particularly affected the emergent sociology of science and the growing field of science and technology studies. In particular, Karin Knorr-Cetina, Bruno Latour, Barry Barnes, Steve Woolgar, and others used social constructionism to relate what science has typically characterized as objective facts to the processes of social construction, with the goal of showing that human subjectivity imposes itself on those facts we take to be objective, not solely the other way around. A particularly provocative title in this line of thought is Andrew Pickering's Constructing Quarks: A Sociological History of Particle Physics. At the same time, Social Constructionism shaped studies of technology – the Sofield, especially on the Social construction of technology, or SCOT, and authors as Wiebe Bijker, Trevor Pinch, Maarten van Wesel, etc.[35][36] Despite its common perception as objective, mathematics is not immune to social constructionist accounts. Sociologists such as Sal Restivo and Randall Collins, mathematicians including Reuben Hersh and Philip J. Davis, and philosophers including Paul Ernest have published social constructionist treatments of mathematics.

Postmodernism

Social constructionism can be seen as a source of the postmodern movement, and has been influential in the field of cultural studies. Some have gone so far as to attribute the rise of cultural studies (the cultural turn) to social constructionism. Within the social constructionist strand of postmodernism, the concept of socially constructed reality stresses the ongoing mass-building of worldviews by individuals in dialectical interaction with society at a time. The numerous realities so formed comprise, according to this view, the imagined worlds of human social existence and activity, gradually crystallized by habit into institutions propped up by language conventions, given ongoing legitimacy by mythology, religion and philosophy, maintained by therapies and socialization, and subjectively internalized by upbringing and education to become part of the identity of social citizens.

In the book The Reality of Social Construction, the British sociologist Dave Elder-Vass places the development of social constructionism as one outcome of the legacy of postmodernism. He writes "Perhaps the most widespread and influential product of this process [coming to terms with the legacy of postmodernism] is social constructionism, which has been booming [within the domain of social theory] since the 1980s."[37]

Criticisms

Social constructionism falls toward the nurture end of the spectrum of the larger nature and nurture debate. Consequently, critics have argued that it generally ignores the contribution made by physical and biological sciences. It equally denies or downplays to a significant extent the role that meaning and language have for each individual, seeking to configure language as an overall structure rather than an historical instrument used by individuals to communicate their personal experiences of the world. This is particularly the case with cultural studies, where personal and pre-linguistic experiences are disregarded as irrelevant or seen as completely situated and constructed by the socio-economical superstructure. As a theory, social constructionism particularly denies the influences of biology on behaviour and culture, or suggests that they are unimportant to achieve an understanding of human behaviour.[38] The scientific consensus is that behaviour is a complex outcome of both biological and cultural influences.[39][40]

In 1996, to illustrate what he believed to be the intellectual weaknesses of social constructionism and postmodernism, physics professor Alan Sokal submitted an article to the academic journal Social Text deliberately written to be incomprehensible but including phrases and jargon typical of the articles published by the journal. The submission, which was published, was an experiment to see if the journal would "publish an article liberally salted with nonsense if (a) it sounded good and (b) it flattered the editors' ideological preconceptions."[41] In 1999, Sokal, with coauthor Jean Bricmont published the book Fashionable Nonsense, which criticized postmodernism and social constructionism.

Philosopher Paul Boghossian has also written against social constructionism. He follows Ian Hacking's argument that many adopt social constructionism because of its potentially liberating stance: if things are the way that they are only because of our social conventions, as opposed to being so naturally, then it should be possible to change them into how we would rather have them be. He then states that social constructionists argue that we should refrain from making absolute judgements about what is true and instead state that something is true in the light of this or that theory. Countering this, he states:

But it is hard to see how we might coherently follow this advice. Given that the propositions which make up epistemic systems are just very general propositions about what absolutely justifies what, it makes no sense to insist that we abandon making absolute particular judgements about what justifies what while allowing us to accept absolute general judgements about what justifies what. But in effect this is what the epistemic relativist is recommending.[42]

Woolgar and Pawluch[43] argue that constructionists tend to 'ontologically gerrymander' social conditions in and out of their analysis.

Social constructionism has been criticized for having an overly narrow focus on society and culture as a causal factor in human behavior, excluding the influence of innate biological tendencies, by psychologists such as Steven Pinker in The Blank Slate[44] as well as by Asian Studies scholar Edward Slingerland in What Science Offers the Humanities.[45] John Tooby and Leda Cosmides used the term "standard social science model" to refer to social-science philosophies that they argue fail to take into account the evolved properties of the brain.[46]

See also

References

- Leeds-Hurwitz, Wendy (2009). "Social construction of reality". In Littlejohn, Stephen W.; Foss, Karen A. (eds.). Encyclopedia of communication theory. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. p. 891. doi:10.4135/9781412959384.n344. ISBN 978-1-4129-5937-7.

- Mr. Sinn (3 February 2016), Theoretical Perspectives: Social Constructionism, retrieved 11 May 2018

- khanacademymedicine (17 September 2013), Social constructionism | Society and Culture | MCAT | Khan Academy, retrieved 12 May 2018

- Jorgensen Phillips (16 March 2019). "Discourse Analysis" (PDF).

- "Social constructionism". Study Journal. 4 December 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- "Social Constructionism | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- Walter Lippmann (1922), Public Opinion, Wikidata Q1768450, pp. 16, 20.

- Woodruff Smith, David (2018). "Phenomenology". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, California: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054 – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Fairhurst, Gail T.; Grant, David (1 May 2010). "The Social Construction of Leadership: A Sailing Guide". Management Communication Quarterly. Thouisand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. 24 (2): 171–210. doi:10.1177/0893318909359697. ISSN 0893-3189.

- Janet Tibaldo (19 September 2013). "Discourse Theory".

- Lock, Andy; Strong, Tom (2010). Social Constructionism: Sources and Stirrings in Theory and Practice. Cambrdge, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–29. ISBN 978-0521708357.

- Leeds-Hurwitz, pgs. 8-9

- Bannister, Donald; Mair, John Miller (1968). The Evaluation of Personal Constructs. London, England: Academic Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0120779505.

- Kelly, George (1955). The Psychology of Personal Constructs. New York City: W.W. Norton. p. 32. ISBN 978-0415037976.

- Mair, John Miller (1977). "The Community of Self". In Bannister, Donald (ed.). New Perspectives in Personal Construct Theory. London, England: Academic Press. pp. 125–149. ISBN 978-0120779406.

- Neimeyer, Robert A.; Levitt, Heidi (January 2000). "What's narrative got to do with it? Construction and coherence in accounts of loss". Journal of Loss and Trauma. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Brunner Routledge: 401–412.

- Procter, Harry G. (2015). "Family Construct Psychology". In Walrond-Skinner, Sue (ed.). Developments in Family Therapy: Theories and Applications Since 1948. London, England: Routledge & Kega. pp. 350–367. ISBN 978-0415742603.

- Stojnov, Dusan; Butt, Trevor (2002). "The relational basis of personal construct psychology". In Neimeyer, Robert A.; Neimeyer, Greg J. (eds.). Advances of personal construct theory: New directions and perspectives. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishing. pp. 81–113. ISBN 978-0275972943.

- Harré, R., & Gillett, D. (1994). The discursive mind. London, UK: Sage

- Shotter, J.; Lannamann, J. (2002). "The situation of social constructionism: Its imprisonment within the ritual of theory-criticism-and-debate". Theory & Psychology. 12 (5): 577–609. doi:10.1177/0959354302012005894.

- Harré, R (2002). "Public sources of the personal mind: Social constructionism in context". Theory & Psychology. 12 (5): 611–623. doi:10.1177/0959354302012005895.

- Stam, H.J. (2001). "Introduction: Social constructionism and its critiques". Theory & Psychology. 11 (3): 291–296. doi:10.1177/0959354301113001.

- Burr, V. (1995), An introduction to social constructionism. London, UK: Routledge

- Botella, L. (1995). Personal construct psychology, constructivism and postmodern thought. In R.A. Neimeyer & G.J. Neimeyer (Eds.), Advances in personal construct psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 3–35). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Burkitt, I (1996). "Social and personal constructs: A division left unresolved". Theory & Psychology. 6: 71–77. doi:10.1177/0959354396061005.

- Burr, V. (1992). Construing relationships: Some thoughts on PCP and discourse. In A. Thompson & P. Cummins (Eds.), European perspectives in personal construct psychology: Selected papers from the inaugural conference of the EPCA (pp. 22–35). Lincoln, UK: EPCA.

- Butt, T.W. (2001). "Social action and personal constructs". Theory & Psychology. 11: 75–95. doi:10.1177/0959354301111007.

- Mancuso, J (1998). "Can an avowed adherent of personal-construct psychology be counted as a social constructions?". Journal of Constructivist Psychology. 11 (3): 205–219. doi:10.1080/10720539808405221.

- Raskin, J.D. (2002). "Constructivism in psychology: Personal construct psychology, radical constructivism, and social constructionism". American Communication Journal. 5 (3): 1–25.

- Jelena Pavlović (11 May 2011). "Personal construct psychology and social constructionism are not incompatible: Implications of a reframing". Theory & Psychology. 21 (3): 396–411. doi:10.1177/0959354310380302.

- Pavlović, Jelena (11 May 2011). "Personal construct psychology and social constructionism are not incompatible: Implications of a reframing". Theory & Psychology. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. 21 (3): 396–411. doi:10.1177/0959354310380302.

- von Glasersfeld, Ernst (1995). Radical Constructivism: A Way of Knowing and Learning. London: Routledge.; Palincsar, A.S. (1998). "Social constructivist perspectives on teaching and learning". Annual Review of Psychology. 49: 345–375. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.345. PMID 15012472.

- Gary W. Potter; Victor W. Kappeler, eds. (1996), Constructing Crime: Perspectives on Making News and Social Problems, Waveland Press, Wikidata Q96343487, p. 2.

- Leeds-Hurwitz, Wendy (29 June 2016). Moy, Patricia (ed.). Social construction. Journal of Communication. Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199756841-0106.

- Pinch, T. J. (1996). The Social Construction of Technology: a Review. In R. Fox (Ed.), Technological Change; Methods and Themes in the History of Technology (pp. 17 – 35). Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.

- Wesel, M. v. (2006). Why we do not always get what we want; The power imbalance in the Social Shaping of Technology (final draft 29 June 2006). Unpublished Master Thesis, Universiteit Maastricht, Maastricht (Look for the latest version here).

- Dave Elder-Vass. 2012.The Reality of Social Construction. Cambridge University Press, 4

- Sokal, A., & Bricmont, J. (1999). Fashionable Nonsense: Postmodern Intellectuals' Abuse of Science. NY: Picador.

- Francsis, D., & Kaufer, D. (2011). Beyond Nature vs. Nurture. The Scientist. 1 October 2011

- Ridly, M. (2004). The Agile Gene: How Nature Turns on Nurture. NY: Harper.

- Sokal, Alan D. (May 1996). "A Physicist Experiments With Cultural Studies". Lingua Franca. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- Paul Boghossian, Fear of Knowledge: Against Relativism and Conmstructivism, Oxford University Press, 2006, 152pp, hb/pb, ISBN 0-19-928718-X.

- Woolgar, S; Pawluch, D (1985). "Ontological gerrymandering: The anatomy of social problems explanations". Social Problems. 32 (3): 214–27. doi:10.1525/sp.1985.32.3.03a00020.

- Pinker, Steven (2016). The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Penguin Books. ISBN 9781101200322.

- Slingerland, Edward (2008). What Science Offers the Humanities. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139470360.

- Barkow, J., Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. 1992. The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Further reading

Books

- Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality : A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (Anchor, 1967; ISBN 0-385-05898-5).

- Joel Best, Images of Issues: Typifying Contemporary Social Problems, New York: Gruyter, 1989

- Ian Hacking, The Social Construction of What? Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999; ISBN 0-674-81200-X

- John Searle, The Construction of Social Reality. New York: Free Press, 1995; ISBN 0-02-928045-1 .

- Charles Arthur Willard, Liberalism and the Problem of Knowledge: A New Rhetoric for Modern Democracy Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996; ISBN 0-226-89845-8.

- Vivien Burr. Social Constructionism, 2nd ed. Routledge 2003.

- Wilson, D. S. (2005), "Evolutionary Social Constructivism". In J. Gottshcall and D. S. Wilson, (Eds.), The Literary Animal: Evolution and the Nature of Narrative. Evanston, IL, Northwestern University Press; ISBN 0-8101-2286-3. Full text

- Sal Restivo and Jennifer Croissant, "Social Constructionism in Science and Technology Studies" (Handbook of Constructionist Research, ed. J.A. Holstein & J.F. Gubrium) Guilford, NY 2008, 213–229; ISBN 978-1-59385-305-1

- Ellul, Jacques. Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes. Trans. Konrad Kellen & Jean Lerner. New York: Knopf, 1965. New York: Random House/ Vintage 1973

- Paul Ernest, (1998), Social Constructivism as a Philosophy of Mathematics; Albany, New York: State University of New York Press

- Kenneth Gergen, (2015, 3d edition, first 1999), An Invitation to Social Construction. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Glasersfeld, Ernst von (1995), Radical Constructivism: A Way of Knowing and Learning. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Hibberd, Fiona J. (2005), Unfolding Social Constructionism. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-22974-4

- André Kukla (2000), Social Constructivism and the Philosophy of Science, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-23419-0, ISBN 978-0-415-23419-1

- Poerksen, Bernhard (2004), The Certainty of Uncertainty: Dialogues Introducing Constructivism. Exeter: Imprint-Academic.

- Schmidt, Siegfried J. (2007), Histories and Discourses: Rewriting Constructivism. Exeter: Imprint-Academic.

- Sheila McNamee and Kenneth Gergen (1999). Relational Responsibility: Resources for Sustainable Dialogue. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage, Inc. ISBN 0-7619-1094-8.

- Sheila McNamee and Kenneth Gergen (Eds.) (1992). Therapy as Social Construction. London: Sage ISBN 0-8039-8303-4.

- Lowenthal, P., & Muth, R. (2008). Constructivism. In E. F. Provenzo, Jr. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the social and cultural foundations of education (pp. 177–179). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Paul Boghossian (2006). Fear of Knowledge: Against Relativism and Constructivism. Oxford University Press. Online review: http://ndpr.nd.edu/news/25184/?id=8364

- Darin Weinberg. 2014. Contemporary Social Constructionism: Key Themes. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press

Articles

- Kitsuse JI, Spector M. "Toward a sociology of social problems: Social conditions, value-judgements, and social problems", Social Problems, 20(4) 407-19, 1973

- Mallon, Ron, "Naturalistic Approaches to Social Construction", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- Metzner, Andreas (1998), "Constructions of Environmental Issues in Scientific and Public Discourse", in: Mueller, F.; Leupelt, M. (Eds.): Eco Targets, Goal Functions and Orientors. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York (Springer Publishers) 1998, pp. 171–192

- Drost, Alexander. "Borders. A Narrative Turn – Reflections on Concepts, Practices and their Communication", in: Olivier Mentz and Tracey McKay (eds.), Unity in Diversity. European Perspectives on Borders and Memories, Berlin 2017, pp. 14–33.

External links

| Library resources about Social constructionism |

| Look up social constructionism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

.svg.png)