Tallinn

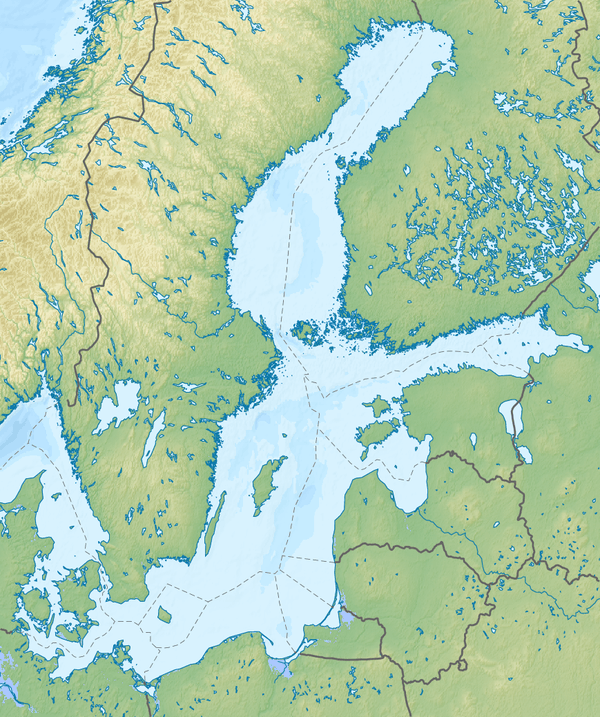

Tallinn (/ˈtɑːlɪn, ˈtælɪn/;[4][5][6] Estonian: [ˈtɑlʲˑinˑ]; names in other languages) is the capital, primate and the most populous city of Estonia. Located in the northern part of the country, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, it has a population of 437,619 in 2020.[1] Administratively a part of Harju County, Tallinn is the main financial, industrial and cultural centre of Estonia; the second largest city, Tartu, is located in the southern part of Estonia, 186 kilometres (116 mi) southeast of Tallinn. Tallinn is located 80 kilometres (50 mi) south of Helsinki, Finland, 320 kilometres (200 mi) west of Saint Petersburg, Russia, 300 kilometres (190 mi) north of Riga, Latvia, and 380 kilometres (240 mi) east of Stockholm, Sweden. It has close historical ties with these four cities. From the 13th century until the first half of the 20th century Tallinn was known in most of the world by its historical German name Reval.

Tallinn | |

|---|---|

Toompea hill | |

Logo | |

| Coordinates: 59°26′14″N 24°44′43″E | |

| Country | Estonia |

| County | Harju |

| First historical record | 1219 |

| First possible appearance on map | 1154 |

| Town rights | 1248 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mihhail Kõlvart |

| Area | |

| • Total | 159.2 km2 (61.5 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 9 m (30 ft) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 437,619 |

| • Rank | 1st in Estonia |

| • Density | 2,700/km2 (7,100/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Tallinner (English) tallinlane (Estonian) |

| Resident registration (1.08.2019) | |

| • Total | 441,062 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| GRP (Metro)[3] | 2018 |

| - Total | €14.2 billion ($17B) |

| - Per capita | €32,800 ($38,697) |

| Website | tallinn |

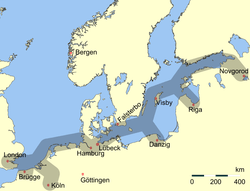

Tallinn, first mentioned in 1219, received city rights in 1248,[7] but the earliest human settlements date back 5,000 years.[8] The first recorded claim over the land was laid by Denmark in 1219, after a successful raid of Lyndanisse led by king Valdemar II, followed by a period of alternating Scandinavian and Teutonic rulers. Due to its strategic location, the city became a major trade hub, especially from the 14th to the 16th century, when it grew in importance as part of the Hanseatic League. Tallinn's Old Town is one of the best preserved medieval cities in Europe and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[9]

Tallinn has the highest number of start-ups per person among European countries[10] and is a birthplace of many international high technology companies, including Skype and Transferwise.[11] The city is to house the headquarters of the European Union's IT agency.[12] Providing to the global cybersecurity it is the home to the NATO Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence. Tallinn is ranked as a global city and has been listed among the top ten digital cities in the world.[13] The city was a European Capital of Culture for 2011, along with Turku in Finland.

Etymology

Historical names

In 1154, a town called قلون (Qlwn[14] or Qalaven, possibly derivations of Kalevan or Kolyvan)[15][16] was put on the world map of the Almoravid by the Arab cartographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, who described it as "a small town like a large castle" among the towns of 'Astlanda'. It was suggested that Quwri may have denoted a predecessor of the modern city.[17][18] Another possibly one of the earliest name of Tallinn is Kolyvan (Russian: Колывань), which has been discovered from East Slavic chronicles and may somehow be connected to the Estonian mythical hero Kalev.[19][20] However, a number of modern historians have considered connecting al-Idrisi placename(s) with Tallinn unfounded and erroneous.[21][7][22][23]

Henry of Livonia in his chronicle called the town with the name that is also known to have been used up to the 13th century by Scandinavians: Lindanisa (or Lyndanisse in Danish,[24][25][26] Lindanäs in Swedish and Ledenets in Old East Slavic). It has been suggested that the archaic Estonian word linda is similar to the Votic word lidna 'castle, town'. According to this suggestion, nisa would have the same meaning as niemi 'peninsula', producing Kesoniemi, the old Finnish name for the city.[27]

Another ancient historical name for Tallinn is Rääveli in Finnish. The Icelandic Njal's saga mentions Tallinn and calls it Rafala, which is probably based on the primitive form of Revala. This name originated from Latin Revelia (Revala or Rävala in Estonian), the adjacent ancient name of the surrounding area. After the Danish conquest in 1219, the town became known in the German, Swedish and Danish languages as Reval (Latin: Revalia). Reval was in official use in Estonia until 1918.

Modern name

.svg.png)

The name Tallinn(a) is Estonian. It is usually thought to be derived from Taani-linn(a), (meaning 'Danish-town) (Latin: Castrum Danorum), after the Danes built the castle in place of the Estonian stronghold at Lindanisse. However, it could also have come from tali-linna ('winter-castle or town'), or talu-linna ('house/farmstead-castle or town'). The element -linna, like Germanic -burg and Slavic -grad / -gorod, originally meant 'fortress', but is used as a suffix in the formation of town names.

The previously-used official names in German ![]()

At first, both forms Tallinna and Tallinn were used.[28] The United States Board on Geographic Names adopted the form Tallinn between June 1923 and June 1927.[29] Tallinna in Estonian denotes the genitive case of the name, as in Tallinna Reisisadam ('the Port of Tallinn').

In Russian, the spelling of the name was changed from Таллинн to Таллин[30] (Tallin) by the Soviet authorities in the 1950s, and this spelling is still officially sanctioned by the Russian government, while Estonian authorities have been using the spelling Таллинн in Russian-language publications since the restoration of independence. The form Таллин is also used in several other languages in some of the countries that emerged from the former Soviet Union. Due to the Russian spelling, the form Tallin is sometimes found in international publications; it is also the official form in Spanish.[31]

Other variations of modern spellings include Tallinna in Finnish, Tallina in Latvian and Talinas in Lithuanian.

History

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 822 |

| Inscription | 1997 (21st session) |

| Area | 113ha |

| Buffer zone | 2,253 ha |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The first traces of human settlement[8] found in Tallinn's city centre by archeologists are about 5,000 years old. The comb ceramic pottery found on the site dates to about 3000 BCE and corded ware pottery c. 2500 BCE.[32]

.jpg)

Around 1050, the first fortress was built on Tallinn Toompea.[15]

As an important port for trade between Russia and Scandinavia, it became a target for the expansion of the Teutonic Knights and the Kingdom of Denmark during the period of Northern Crusades in the beginning of the 13th century when Christianity was forcibly imposed on the local population. Danish rule of Tallinn and Northern Estonia started in 1219.

In 1285, Tallinn, then known more widely as Reval, became the northernmost member of the Hanseatic League – a mercantile and military alliance of German-dominated cities in Northern Europe. The king of Denmark sold Reval along with other land possessions in northern Estonia to the Teutonic Knights in 1346. Medieval Reval enjoyed a strategic position at the crossroads of trade between Western and Northern Europe and Russia. The city, with a population of about 8,000, was very well fortified with city walls and 66 defence towers.

A weather vane, the figure of an old warrior called Old Thomas, was put on top of the spire of the Tallinn Town Hall in 1530. Old Thomas has later become a popular symbol of the city.

Already in the early years of the Protestant Reformation the city converted to Lutheranism. In 1561, Reval became a dominion of Sweden.

During the Great Northern War, plague stricken Tallinn along with Swedish Estonia and Livonia capitulated to Imperial Russia in 1710, but the local self-government institutions (Magistracy of Reval and Chivalry of Estonia) retained their cultural and economical autonomy within Imperial Russia as the Governorate of Estonia. The Magistracy of Reval was abolished in 1889. The 19th century brought industrialisation of the city and the port kept its importance. During the last decades of the century Russification measures became stronger. Off the coast of Reval, in June 1908, Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra of Russia, along with their children, met their mutual uncle and aunt, Britain's King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, an act which was seen as a royal confirmation of the Anglo-Russian Entente of the previous year, and which was the first time a reigning British monarch had visited Russia.[33]

On 24 February 1918, the Independence Manifesto was proclaimed in Reval (Tallinn), followed by Imperial German occupation and a war of independence with Soviet Russia, after which Tallinn became the capital of independent Estonia. During World War II, Estonia was first occupied by the Red Army and annexed into the USSR in 1940, then occupied by Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1944. When German forces invaded there were about 1,000 remaining Jews in the city of Tallinn, nearly all of whom would die in the Holocaust at the hands of the Nazis before the war's end.[34] After the German retreat in 1944, the city was occupied again by the Soviets. After the annexation of Estonia into the USSR, Tallinn became formally "the capital city" of the Estonian SSR within the Soviet Union.

During the 1980 Summer Olympics, the sailing (then known as yachting) events were held at Pirita, north-east of central Tallinn. Many buildings, such as the Tallinn TV Tower, "Olümpia" hotel, the new Main Post Office building, and the Regatta Centre, were built for the Olympics.

In 1991, an independent democratic Estonian nation was reestablished and a period of quick development as a modern European capital ensued. Tallinn became the capital of a de facto independent country once again on 20 August 1991.

Tallinn has historically consisted of three parts:

- The Toompea (Domberg) or "Cathedral Hill", which was the seat of the central authority: first the Danish captains, then the komturs of the Teutonic Order, and Swedish and Russian governors. It was until 1877 a separate town (Dom zu Reval), the residence of the aristocracy; it is today the seat of the Estonian parliament, government and some embassies and residencies.

- The Old Town, which is the old Hanseatic town, the "city of the citizens", was not administratively united with Cathedral Hill until the late 19th century. It was the centre of the medieval trade on which it grew prosperous.

- The Estonian town forms a crescent to the south of the Old Town, where the Estonians came to settle. It was not until the mid-19th century that ethnic Estonians replaced the local Baltic Germans as the majority among the residents of Tallinn.

The city of Tallinn has never been razed; that was the fate of Tartu, the university town 200 km (124 mi) south, which was pillaged in 1397 by the Teutonic Order. Around 1524 Catholic churches in many towns in Estonia, including Tallinn, were pillaged as part of the Reformational fervor: this occurred throughout Europe. Although extensively bombed by Soviet air forces during the later stages of World War II, much of the medieval Old Town still retains its charm. The Tallinn Old Town (including Toompea) became a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site in 1997.

At the end of the 15th century a new 159 m (521.65 ft) high Gothic spire was built for St. Olaf's Church. Between 1549 and 1625 it may have been the tallest building in the world. After several fires and subsequent periods of rebuilding, its overall height is now 123 m (403.54 ft).

Geography

Tallinn is situated on the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland, in north-western Estonia.

The largest lake in Tallinn is Lake Ülemiste (9.44 km2 (3.6 sq mi)). It is the main source of the city's drinking water. Lake Harku is the second largest lake within the borders of Tallinn and its area is 1.6 square kilometres (0.6 sq mi). Tallinn does not lie on a major river. The only significant river in Tallinn is Pirita River in Pirita, a city district counted as a suburb. Historically, the small Härjapea River flowed from Lake Ülemiste through the town into the sea, but the river was diverted for sewage in the 1930s and has since completely disappeared from the cityscape. References to it still remain in the street names Jõe (from Jõgi, river) and Kivisilla (from Kivisild, stone bridge).

A limestone cliff runs through the city. It can be seen at Toompea, Lasnamäe and Astangu. However, Toompea is not a part of the cliff, but a separate hill.

The highest point in Tallinn, at 64 meters above sea level, is situated in Hiiu, Nõmme District, in the south-west of the city.

The length of the coast is 46 kilometres (29 miles). It comprises three bigger peninsulas: Kopli peninsula, Paljassaare peninsula and Kakumäe peninsula. The city has a number of public beaches, including those at Pirita, Stroomi, Kakumäe, Harku and Pikakari.[35]

Geology

The geology under the city of Tallinn is made up of rocks and sediments of different composition and age. Youngest are the Quaternary deposits. The material of these deposits are till, varved clay, sand, gravel and pebbles that are of glacial, marine and lacustrine origin. Some of the Quaternary deposits are valuable as they constitute aquifers or, as in the case of gravels and sands, are used as construction materials. The Quaternary deposits are the fill of valleys that are now buried. The buried valleys of Tallinn are carved into older rock likely by ancient rivers to be later modified by glaciers. While the valley fill is made up of Quaternary sediments the valleys themselves originated from erosion that took place before the Quaternary.[36] The substrate into which the buried valleys were carved is made up of hard sedimentary rock of Ediacaran, Cambrian and Ordovician age. Only the upper layer of Ordovician rocks protrudes from the cover of younger deposits cropping out in the Baltic Klint at the coast and at a few places inland. The Ordovician rocks are made up from top to bottom of a thick layer of limestone and marlstone, then a first layer of argillite followed by first layer of sandstone and siltstone and then another layer of argillite also followed by sandstone and siltstone. In other places of the city hard sedimentary rock is only to be found beneath Quaternary sediments at depths reaching as much as 120 meters below sea level. Underlying the sedimentary rock are the rocks of the Fennoscandian Craton including gneisses and other metamorphic rocks with volcanic rock protoliths and rapakivi granites. The mentioned rocks are much older than the rest (Paleoproterozoic age) and do not crop out anywhere in Estonia.[36]

Climate

Tallinn has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb) with warm, mild summers and cold, snowy winters.[37] Winters are cold but mild for its latitude, owing to its coastal location. The average temperature in February, the coldest month, is −4.3 °C (24.3 °F). During the winter months, temperatures tend to hover close to the freezing mark but mild spells of weather can push temperatures above 0 °C (32 °F), occasionally reaching above 5 °C (41 °F) while cold air masses can push temperatures below −18 °C (0 °F) an average of 6 days a year. Snowfall is common during the winter months. Winters are cloudy[38] and are characterised by low amounts of sunshine, ranging from only 0.5 hours of sunshine per day in December to 4.1 hours in March.[39] At the winter solstice daylight lasts for only 6 hours.[40]

Spring starts out cool, with freezing temperatures common in March and April but gradually becomes warmer in late May when daytime temperatures average 15.2 °C (59.4 °F) although nighttime temperatures still remain cool, averaging −1.0 to 5.2 °C (30.2 to 41.4 °F) from March to May. Snowfall is common in March and can occur in April.[38]

Summers are mild with daytime temperatures hovering around 19 to 21 °C (66 to 70 °F) and nighttime temperatures averaging between 9.6 to 12.7 °C (49.3 to 54.9 °F) from June to August. The warmest month is usually July, with an average of 17.2 °C (63.0 °F). During summer, partly cloudy or clear days are common[38] and it is the sunniest season, ranging from 7.4 hours of sunshine in August to 10.1 hours in June although precipitation is higher during these months.[39] As a consequence of its high latitude, at the summer solstice, daylight lasts for more than 18 hours and 30 minutes.[41]

Fall starts out mild, with a September average of 11.3 °C (52.3 °F) and increasingly becomes cooler and cloudier towards the end of November.[38] In the early parts of fall, temperatures commonly reach 15 °C (59 °F) on some days and at least one day above 21 °C (70 °F) in September. In the latter months of fall, freezing temperatures become more common and snowfall can occur.

Tallinn receives 618 millimeters (24.3 in) of precipitation annually which is evenly distributed throughout the year although March and April are the driest months, averaging about 30 millimeters (1.2 in) while July and August are the wettest months with 74 millimeters (2.9 in) of precipitation. The average humidity is 81%, ranging from a high of 88% to a low of 69% in May. Tallinn has an average windspeed of 3.5 metres per second (11 ft/s) with winters being the windiest (around 4.0 metres per second (13 ft/s) in January) and summers being the least windy at around 2.9 m/s (9.5 ft/s) in July and August.[38] Extremes range from −32.2 °C (−26.0 °F) in December 1978 and −31.1 °C (−24.0 °F) in January 1940 to 34.3 °C (93.7 °F) in July 1994.[38]

| Climate data for Tallinn, Estonia (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

15.9 (60.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

34.3 (93.7) |

34.2 (93.6) |

28.0 (82.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

34.3 (93.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.0 (30.2) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

2.3 (36.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

18.9 (66.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

0.4 (32.7) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.3 (26.1) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.2 (63.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.3 (52.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −5.9 (21.4) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

0.6 (33.1) |

5.2 (41.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.4 (−24.5) |

−28.7 (−19.7) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−18.8 (−1.8) |

−24.3 (−11.7) |

−31.4 (−24.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56 (2.2) |

36 (1.4) |

37 (1.5) |

32 (1.3) |

36 (1.4) |

64 (2.5) |

84 (3.3) |

86 (3.4) |

67 (2.6) |

78 (3.1) |

70 (2.8) |

57 (2.2) |

704 (27.7) |

| Average rainy days | 10 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 17 | 18 | 16 | 12 | 153 |

| Average snowy days | 19 | 18 | 13 | 5 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 18 | 87 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 85 | 81 | 73 | 69 | 74 | 76 | 79 | 82 | 85 | 88 | 88 | 81 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 25.0 | 55.7 | 129.3 | 202.8 | 292.9 | 285.7 | 307.4 | 240.7 | 151.5 | 87.4 | 28.6 | 18.8 | 1,825.8 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Source: Estonian Weather Service[42][43][44][45], Pogoda.ru.net (rainy and snowy days)[38] and Weather Atlas[46] | |||||||||||||

Administrative districts

| District | Population (November 2017)[47] |

Area[48] | Density |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Haabersti | 45,339 | 22.26 km2 (8.6 sq mi) | 2,036.8/km2 (5,275.3/sq mi) |

| 2. Kesklinn (centre) | 63,406 | 30.56 km2 (11.8 sq mi) | 2,074.8/km2 (5,373.7/sq mi) |

| 3. Kristiine | 33,202 | 7.84 km2 (3.0 sq mi) | 4,234.9/km2 (10,968.5/sq mi) |

| 4. Lasnamäe | 119,542 | 27.47 km2 (10.6 sq mi) | 4,351.7/km2 (11,270.9/sq mi) |

| 5. Mustamäe | 68,211 | 8.09 km2 (3.1 sq mi) | 8,431.5/km2 (21,837.5/sq mi) |

| 6. Nõmme | 39,540 | 29.17 km2 (11.3 sq mi) | 1,355.5/km2 (3,510.7/sq mi) |

| 7. Pirita | 18,606 | 18.73 km2 (7.2 sq mi) | 993.4/km2 (2,572.8/sq mi) |

| 8. Põhja-Tallinn | 60,203 | 15.9 km2 (6.1 sq mi) | 3,786.4/km2 (9,806.6/sq mi) |

For local government purposes, Tallinn is subdivided into 8 administrative districts (Estonian: linnaosad, singular linnaosa). The district governments are city institutions that fulfill, in the territory of their district, the functions assigned to them by Tallinn legislation and statutes.

Each district government is managed by an elder (Estonian: linnaosavanem). They are appointed by the city government on the nomination of the mayor and after having heard the opinion of the administrative councils. The function of the administrative councils is to recommend to the city government and commissions of the city council how the districts should be administered.

The administrative districts are further divided into subdistricts or neighbourhoods (Estonian: asum). Their names and borders are officially defined. There are 84 subdistricts in Tallinn.[49]

Demographics

| Largest ethnic groups[50] | ||

| Ethnic group | Population (2019) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Estonians | 228,821 | 49.38 |

| Russians | 157,696 | 34.03 |

| Ukrainians | 12,717 | 2.74 |

| Belarusians | 5,983 | 1.29 |

| Finns | 2,449 | 0.53 |

| Jews | 1,450 | 0.31 |

| Tatars | 1,020 | 0.22 |

| Lithuanians | 985 | 0.21 |

| Armenians | 983 | 0.21 |

| Latvians | 951 | 0.21 |

| Germans | 783 | 0.17 |

| Poles | 778 | 0.17 |

| Azerbaijanis | 752 | 0.16 |

| Other | 35,391 | 7.64 |

| Unknown | 12,654 | 2.73 |

The population of Tallinn on 1 January 2020 was 437,619.[1]

According to Eurostat, in 2004 Tallinn had one of the largest number of non-EU nationals of all EU member states' capital cities with Russians forming a significant minority (~34% belong to the Russian ethnic group, but a majority now hold Estonian citizenship).[51] Ethnic Estonians make up about 50% of the population (as of 2019).

The official language of Tallinn is Estonian. In 2011, 206,490 (50.1%) spoke Estonian as their native language and 192,199 (46.7%) spoke Russian as their native language. Other spoken languages include Ukrainian, Belarusian and Finnish.[52]

| Year | 1372 | 1772 | 1816 | 1834 | 1851 | 1881 | 1897 | 1925 | 1959 | 1989 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 3,250 | 6,954 | 12,000 | 15,300 | 24,000 | 45,900 | 58,800 | 119,800 | 283,071 | 478,974 | 400,378 | 401,694 | 406,703 | 426,538 | 430,805 | 434,562 | 437,619 |

Economy

Tallinn is the financial and business capital of Estonia. The city has a highly diversified economy with particular strengths in information technology, tourism and logistics. Over half of the Estonian GDP is created in Tallinn.[53] In 2008, the GDP per capita of Tallinn stood at 172% of the Estonian average.[54]

Information technology

In addition to longtime functions as seaport and capital city, Tallinn has seen development of an information technology sector; in its 13 December 2005, edition, The New York Times characterised Estonia as "a sort of Silicon Valley on the Baltic Sea".[55] One of Tallinn's sister cities is the Silicon Valley town of Los Gatos, California. Skype is one of the best-known of several Estonian start-ups originating from Tallinn. Many start-ups originated from the Soviet-era Institute of Cybernetics. In recent years, Tallinn has gradually been becoming one of the main IT centres of Europe, with the Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCD COE) of NATO, the EU Agency for large-scale IT systems and the IT development centres of large corporations, such as TeliaSonera and Kuehne + Nagel being based in the city. Smaller start-up incubators like Garage48 and Game Founders have helped to provide support to teams from Estonia and around the world looking for support, development and networking opportunities.[56]

Tourism

Tallinn receives 4.3 million visitors annually,[57] a figure that has grown steadily over the past decade.

Tallinn's Old Town, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is a major tourist attraction; others include the Seaplane Harbour of Estonian Maritime Museum, the Tallinn Zoo, Kadriorg Park, and the Estonian Open Air Museum. Most of the visitors come from Europe, though Tallinn has also become increasingly visited by tourists from Russia and the Asia-Pacific region.[58]

Tallinn Passenger Port is one of the busiest cruise destinations on the Baltic Sea, serving more than 520,000 cruise passengers in 2013.[59] From year 2011 regular cruise turnarounds in cooperation with Tallinn Airport are organised.

The Tallinn Card is a time-limited ticket to visitors. It allows the holder free use of public transport, free entry to many museums and other places of interest, and discounts or free gifts from shops or restaurants.

Energy

Eesti Energia, a large oil shale to energy company,[60] has its headquarters in Tallinn. The city also hosts the headquarters of Elering, a national electric power transmission system operator and member of ENTSO-E, the Estonian natural gas company Eesti Gaas and energy holding company Alexela Energia, part of Alexela Group. Nord Pool Spot, the largest market for electrical energy in the world, established its local office in Tallinn.

Finance

Tallinn is the financial centre of Estonia and also a strong economic centre in the Scandinavian-Baltic region. Many major banks, such as SEB, Swedbank, Nordea, DNB, have their local offices in Tallinn. LHV Pank, an Estonian investment bank, has its corporate headquarters in Tallinn. Two crypto-currencies exchanges officially recognized by the Estonian government, CoinMetro[61] and DX.Exchange[62] have their headquarters in Tallinn. Tallinn Stock Exchange, part of NASDAQ OMX Group, is the only regulated exchange in Estonia.

Logistics

Port of Tallinn is one of the biggest ports in the Baltic sea region.[63] Old City Harbour has been known as a convenient harbour since the 10th century, but nowadays the cargo operations are shifted to Muuga Cargo Port and Paldiski Southern Port. There is a small fleet of oceangoing trawlers that operate out of Tallinn.[64]

Manufacturing sector

Tallinn industries include shipbuilding, machine building, metal processing, electronics, textile manufacturing. BLRT Grupp has its headquarters and some subsidiaries in Tallinn. Air Maintenance Estonia and AS Panaviatic Maintenance, both based in Tallinn Airport, provide MRO services for aircraft, largely expanding their operations in recent years.

Food processing

Liviko, the maker of Vana Tallinn liqueur, strongly associated with the city, is based in Tallinn. The headquarters of Kalev, a confectionery company and part of the industrial conglomerate Orkla Group, is located in Lehmja, southeast of Tallinn.

Retail

The city draws large numbers of shopping tourists from countries within the region. When new planned retail developments are completed, Tallinn will have almost 2 square metres of shopping floor space per inhabitant. As Estonia is already ranked third in Europe in terms of shopping centre space per inhabitant, ahead of Sweden and being surpassed only by Norway and Luxembourg, it will further improve the positions of the city as the major centre of shopping.[65]

Notable headquarters

Among others:

- NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE)

- European Agency for the operational management of large-scale IT systems in the area of freedom, security and justice[66][67][12] is based in Tallinn.

- Skype has its software development centre located in Tallinn.[68]

- TeliaSonera has its IT development centre located in Tallinn.[69]

- Kuehne + Nagel has its IT centre located in Tallinn.[70]

- Arvato Financial Solutions has its global IT development and innovation centre located in Tallinn.[71]

- Ericsson has one of its biggest production facilities in Europe located in Tallinn, focusing on the production of 4G communication devices.[72]

- Equinor has announced moving the group's financial centre to Tallinn.[73]

Education

Institutions of higher education and science include:

- Baltic Film and Media School

- Estonian Academy of Arts

- Estonian Academy of Security Sciences

- Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre

- Estonian Business School

- Estonian Maritime Academy

- Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church Institute of Theology

- National Institute of Chemical Physics and Biophysics

- Tallinn University

- Tallinn University of Technology

Culture

Museums

Tallinn is home to more than 60 museums and galleries.[74] Most of them are located in Kesklinn, the central district of the city, and cover Tallinn's rich history.

One of the most visited historical museums in Tallinn is the Estonian History Museum, located in Great Guild Hall at Vanalinn, the old part of the city.[75] It covers Estonia's history from prehistoric times up until the end of the 20th century.[76] It features film and hands-on displays that show how Estonian dwellers lived and survived.[76]

The Estonian Maritime Museum provides a detailed overview of nation's seafaring past. This museum in also located in city's Old Town, where it occupies one of Tallinn's former defensive structures – Fat Margaret's Tower.[77] Another historical museum that can be found at city's Old Town, just behind the Town Hall, is Tallinn City Museum. It covers Tallinn's history from pre-history until 1991, when Estonia regained its independence.[78] Tallinn City Museum owns nine more departments and museums around the city,[78] one of which is Tallinn's Museum of Photography, also located just behind the Town Hall. It features permanent exhibition that covers 100 years of photography in Estonia.[79]

Estonia's Museum of Occupation is yet another historical museum located in Tallinn's central district. It covers the 52 years when Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.[80] Not far away is another museum related to the Soviet occupation of Estonia, the KGB Museum, which occupies the 23rd floor of Sokos Hotel Viru. It features equipment, uniforms, and documents of Russian Secret Service agents.[81]

Tallinn is also home to two major natural science museums – Estonian Museum of Natural History and Estonian Health Care Museum, both located in Old Town. The Estonian Museum of Natural Science features several seasonal and temporary themed exhibitions that provide an overview of wildlife in Estonia and around the world.[82] The Estonian Health Care Museum features permanent exhibitions on anatomy and health care; its collections and displays cover the history of medicine in Estonia.[83]

Estonia's capital is also home to many art and design museums. The Estonian Art Museum, the country's biggest art museum, now consists of four branches – Kumu Art Museum, Kadriorg Art Museum, Mikkel Museum, and Niguliste Museum. Kumu Art Museum features the country's largest collection of contemporary and modern art. It also displays Estonian art starting from the early 18th century.[84] Those who are interested in Western European and Russian art may enjoy Kadriorg Art Museum collections, located in Kadriorg Palace, a beautiful Baroque building erected by Peter the Great. It stores and displays about 9,000 works of art from the 16th to 20th centuries.[85] The Mikkel Museum, in Kadriorg Park, displays a collection of mainly Western art – ceramics and Chinese porcelain donated by Johannes Mikkel in 1994. The Niguliste Museum occupies former St. Nicholas' Church; it displays collections of historical ecclesiastical art spanning nearly seven centuries from the Middle Ages to post-Reformation art.

Those that are interested in design and applied art may enjoy the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design collection of Estonian contemporary designs. It displays up to 15.000 pieces of work made of textile art, ceramics, porcelain, leather, glass, jewellery, metalwork, furniture, and product design.[86] To experience more relaxed, culture-oriented exhibits, one may turn to Museum of Estonian Drinking Culture. This museum showcases the historic Luscher & Matiesen Distillery as well as the history of Estonian alcohol production.[87]

Lauluväljak

The Estonian Song Festival (in Estonian: Laulupidu) is one of the largest choral events in the world, listed by the UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. It is held every five years in July on the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds (Lauluväljak) simultaneously with the Estonian Dance Festival.[88] The joint choir has comprised more than 30,000 singers performing to an audience of 80,000.[88][89]

Often referred to as The Singing Nation, the Estonians have one of the biggest collections of folk songs in the world, with written records of about 133,000 folk songs.[90] From 1987, a cycle of mass demonstrations featuring spontaneous singing of national songs and hymns that were strictly forbidden during the years of the Soviet occupation to peacefully resist the illegal oppression. In September 1988, a record 300,000 people, more than a quarter of all Estonians, gathered in Tallinn for a song festival.[91]

Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival

Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival (Estonian: Pimedate Ööde Filmifestival, or PÖFF), is an annual film festival held since 1997 in Tallinn, the capital city of Estonia. PÖFF is the only festival in the Nordic and Baltic region with a FIAPF (International Federation of Film Producers Association) accreditation for holding an international competition programme in the Nordic and Baltic region with 14 other non-specialised festivals, such as Cannes, Berlin, Venice. With over 250 feature films screened each year and over 77500 attendances (2014), PÖFF is one of the largest film events of Northern Europe and cultural events in Estonia in the winter season. During its 19th edition in 2015 the festival screened more than 600 films (including 250+ feature-length films from 80 different countries), bringing over 900 screenings to an audience of over 80, 000 people as well as over 700 accredited guests and journalists from 50 different countries. In 2010 the festival held the European Film Awards ceremony in Tallinn.

Cuisine

The traditional cuisine of Tallinn reflects culinary traditions of the Northern Estonia, the role of the city as a fishing port, and the Baltic German influence. Numerous cafés (Estonian: Kohvik) have played a major role in a social life of the city since the 19th century, as have bars, especially in the Kesklinn district.

The marzipan industry in Tallinn has a very long history. The production of marzipan started in the Middle Ages, almost simultaneously in Tallinn and Lübeck, both members of the Hanseatic League. In 1695, marzipan was mentioned as a medicine, under the designation of Panis Martius, in the price lists of the Tallinn Town Hall Pharmacy.[93] The modern era of marzipan in Tallinn began in 1806, when the Swiss confectioner Lorenz Caviezel set up his confectionery on Pikk Street. In 1864 it was bought and expanded by Georg Stude and now is known as the Maiasmokk café. In the late 19th century marzipan figurines made by Reval confectioners were supplied to the Russian Imperial Family.[94] Today, along with mass production, unique projects are made, such as a 12 kg scale model of the Estonia Theatre.[95]

The most symbolic seafood dish of Tallinn is "Vürtsikilu" – spicy sprats, pickled with a distinctive set of spices including black pepper, allspice and cloves. Making vürtsikilu presumably originated from the city outskirts, beginning in the late 18th or the early 19th century. In 1826 Tallinn merchants exported nearly 40,000 cans of vürtsikilu to Saint Petersburg, then the capital of the Russian Empire.[96] A closely associated dish is a "Kiluvõileib" – a traditional rye bread open sandwich with a thin layer of butter and a layer of vürtsikilu as a topping. Boiled egg slices, mayonnaise and culinary herbs are optional extra toppings.

Alcoholic beverages produced in the city include beers, vodkas, and liqueurs, the latter (such as Vana Tallinn) being the most characteristic. Also, the number of craft beer breweries has expanded sharply in Tallinn over the last decade, entering local and regional markets.

Tourism

.jpg)

What can arguably be considered to be Tallinn's main attractions are located in the old town of Tallinn (divided into a "lower town" and Toompea hill) which is easily explored on foot. The eastern parts of the city, notably Pirita (with Pirita Convent) and Kadriorg (with Kadriorg Palace) districts, are also popular destinations, and the Estonian Open Air Museum in Rocca al Mare, west of the city, preserves aspects of Estonian rural culture and architecture.

Toompea – Upper Town

This area was once an almost separate town, heavily fortified, and has always been the seat of whatever power that has ruled Estonia. The hill occupies an easily defensible site overlooking the surrounding districts. The major attractions are the medieval Toompea Castle (today housing the Estonian Parliament, the Riigikogu), the Lutheran St Mary's Cathedral, also known as the Dome Church (Estonian: Toomkirik), and the Russian Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Cathedral.

All-linn – Lower Town

This area is one of the best preserved medieval towns in Europe and the authorities are continuing its rehabilitation. Major sights include the Town Hall square (Estonian: Raekoja plats), the city wall and towers (notably "Fat Margaret" and "Kiek in de Kök") as well as a number of medieval churches, including St Olaf's, St. Nicholas' and the Church of the Holy Ghost. The Catholic Cathedral of St Peter and St Paul is also in the Lower Town.

Kadriorg

Kadriorg is 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) east of the city centre and is served by buses and trams. Kadriorg Palace, the former palace of Peter the Great, built just after the Great Northern War, now houses the foreign art department of the Art Museum of Estonia, the presidential residence and the surrounding grounds include formal gardens and woodland.

The main building of the Art Museum of Estonia, Kumu (Estonian: Kunstimuuseum, Art Museum), was built in 2006 and lies in Kadriorg park. It houses an encyclopaedic collection of Estonian art, including paintings by Carl Timoleon von Neff, Johann Köler, Eduard Ole, Jaan Koort, Konrad Mägi, Eduard Wiiralt, Henn Roode and Adamson-Eric, among others.

Pirita

This coastal district is a further 2 kilometres north-east of Kadriorg. The marina was built for the Moscow Olympics of 1980, and boats can be hired on the Pirita River. Two kilometres inland are the Botanic Gardens and the Tallinn TV Tower.

Music culture

Tallinn has a few music venues for live music such as Kultuurikatel/Kanala, Ptarmigan, Tapper, EKKM – Museum and nightlife, DM Baar. Yearly festivals like Tallinn Music Week and Stalker Festival take place.

Old Town of Tallinn

Old Town of Tallinn.jpg) Panorama of the central Town Hall Square (Raekoja plats)

Panorama of the central Town Hall Square (Raekoja plats)

Transport

City transport

The city operates a system of bus (73 lines), tram (4 lines) and trolley-bus (4 lines) routes to all districts. A flat-fare system is used. The ticket-system is based on prepaid RFID cards available in kiosks and post offices. In January 2013, Tallinn became the first European capital to offer a fare-free service on buses, trams and trolleybuses within the city limits. This service is available to residents who register with the municipality.[97]

Air

The Lennart Meri Tallinn Airport is about 4 kilometres (2 miles) from Town Hall square (Raekoja plats). There is a tram (Line Number: 4 and local bus connection between the airport and the edge of the city centre (bus no. 2). The nearest railway station Ülemiste is only 1.5 km (0.9 mi) from the airport.

The construction of the new section of the airport began in 2007 and was finished in summer 2008.

There has been a helicopter service to and from Helsinki operated by Copterline and taking 18 minutes to cross the Gulf of Finland. The Copterline Tallinn terminal is located adjacent to Linnahall, five minutes from the city centre. After a crash near Tallinn in August 2005, service was suspended but restarted in 2008 with a new fleet.[98] The operator cancelled it again in December 2008,[99] on grounds of unprofitability. On 15 February 2010, Copterline filed for bankruptcy, citing inability to keep the company profitable. In 2011 Copterline started again operating the Tallinn – Helsinki flights. In 2016, Copterline OÜ filed for bankruptcy[100] and there are no scheduled helicopter flights from Tallinn.

Ferry

Several ferry operators, Viking Line, Linda Line, Tallink and Eckerö Line, connect Tallinn to Helsinki, Mariehamn, Stockholm, and St. Petersburg. Passenger lines connect Tallinn to Helsinki (83 km (52 mi) north of Tallinn) in approximately 2–3.5 hours by cruiseferries.

Railroad

The Elron railway company operates train services from Tallinn to Tartu, Valga, Türi, Viljandi, Tapa, Narva, Orava, Koidula. Buses are also available to all these and various other destinations in Estonia, as well as to Saint Petersburg in Russia and Riga, Latvia. The Russian railways company operates a daily international sleeper train service between Tallinn – Moscow.

Tallinn also has a commuter rail service running from Tallinn's main rail station in two main directions: east (Aegviidu) and to several western destinations (Pääsküla, Keila, Riisipere, Paldiski, and Kloogaranna). These are electrified lines and are used by the Elron railroad company. Stadler FLIRT EMU and DMU units are in service since July 2013. The first electrified train service in Tallinn was opened in 1924 from Tallinn to Pääsküla, a distance of 11.2 km (7.0 mi).

The Rail Baltica project, which will link Tallinn with Warsaw via Latvia and Lithuania, will connect Tallinn with the rest of the European rail network. A tunnel has been proposed between Tallinn and Helsinki, though it remains at a planning phase.

Roads

The Via Baltica motorway (part of European route E67 from Helsinki to Prague) connects Tallinn to the Lithuanian/Polish border through Latvia.

Frequent and affordable long-distance bus routes connect Tallinn with other parts of Estonia.

On 9 October 2013, the 320-meter-long Ülemiste tunnel was first opened.

Notable people

Pre 1900

- Michael Sittow (ca. 1469–1525) An Estonian painter, trained in the tradition of Early Netherlandish painting. He was one of the most important Flemish painters of the era.

- Jacob Johan Hastfer (1647 in Tallinn – 1695) Swedish officer and governor of the Livonia province between 1687 and 1695

- Alexander Friedrich von Hueck (1802–1842) Baltic-German professor of anatomy at University of Tartu, a notable estophile.

- Julius Gottlieb Iversen (1823–1900) Russian phalerist (scholar of medals), taught Greek and Latin

- Carl Wilhelm Hiekisch (1840–1901) was a Baltic German geographer.

- Marie Under (1883–1980) one of the greatest Estonian poets, nominated for the Nobel prize in literature 8 times

- Edmund August Friedrich Russow (1841–1897) Baltic German biologist, researched plant anatomy and histology

- Alfred Rosenberg (1893–1946), German theorist and Nazi official, executed for war crimes

1900 to 1930

- Ants Oras (1900–1982) Estonian translator and writer, studied pause patterns in English Renaissance dramatic blank verse

- Vidrik "Frits" Rootare (1906–1981) Estonian chess player

- Andrus Johani (1906–1941) painter from Estonia, executed in Tartu prison

- Edmund S. Valtman (1914–2005) Estonian-American cartoonist, won the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning

- Evald Okas (1915–2011) Estonian painter, probably best known for his portraits of nudes

- Evi Rauer (1915–2004) Estonian stage, film and television actress and television director

- Paul Kuusberg (1916–2003) Estonian writer, particularly of novellas

- Ellen Liiger (1918–1987) Estonian stage, TV, radio and film actress and theatre teacher whose stage career began at age six

- Udo Kasemets (1919–2014) Estonian-born Canadian composer of orchestral, vocal, piano and electroacoustic works

- Jaan Kross (1920–2007) Estonian writer of novels

- Vincent Zigas (1920–1983) medical officer in Papua New Guinea during the 1950s

- Harry Männil (1920–2010), Estonian businessman, art collector, and Venezuelan resident

- Kaljo Raid (1921–2005) Estonian composer, cellist and pastor

- Vello Viisimaa (1928–1991) Estonian opera singer and stage actor, appeared mostly in operettas.

- Lennart Georg Meri (1929–2006) Estonian politician, writer, film director, statesman, second President of Estonia, 1992 to 2001

- Eino Tamberg (1930–2010) Estonian composer, promoted neoclassicism in Estonian music

1930 to 1950

- Vladimir-Georg Karassev-Orgusaar (1931–2015) was an Estonian film director and member of the Congress of Estonia

- Martin Puhvel (1933–2016) a literature researcher, professor emeritus at McGill University for old and medieval English literature

- Ingrid Rüütel (born 1935) Estonian folklorist and philologist, 2001–2006 First Lady of Estonia, married to President Arnold Rüütel

- Peter Peet Silvester (1935–1996) electrical engineer, particularly numerical analysis of electromagnetic fields

- Jüri Arrak (born 1936) Estonian artist and painter

- Enn Vetemaa (1936–2017) Estonian writer, master of the Estonian Modernist short novel

- Arvo Antonovich Mets (1937–1997) Estonian-born Russian poet, master of Russian free verse

- Mikk Mikiver (1937–2006) Estonian stage and film actor and theater director

- Linnart Mäll (1938–2010) Estonian historian, orientalist, translator and politician.

- Ene Riisna (born 1938) Estonian-born American television producer, known for her work on the American news show 20/20.

- Andres Tarand (born 1940) Estonian politician, Prime Minister of Estonia and Member of the European Parliament

- Leila Säälik (born 1941) Estonian stage, film and radio actress.

- Paul-Eerik Rummo (born 1942) Estonian poet and politician

- Eili Sild (born 1942) Estonian stage, film, television and radio actress

- Kalle Lasn (born 1942) Estonian-Canadian film maker, author, magazine editor and activist

- Urjo Kareda (1944–2001) Estonian-born Canadian theatre and music critic, dramaturge and stage director

- Mari Lill (born 1945) Estonian stage, film and TV actress

- Sulev Mäeltsemees (born 1947) Estonian public administration and local government scholar

- Siiri Oviir (born 1947) Estonian politician and Member of the European Parliament

- Lepo Sumera (1950–2000) Estonian composer and teacher and Minister of Culture from 1988 to 1992

1950 to 1970

- Urmas Alender (1953–1994) Estonian singer and musician, the vocalist of popular Estonian bands Ruja and Propeller

- Ivo Lill (born 1953) Estonian glass artist

- Ain Lutsepp (born 1954) Estonian actor and politician.

- Kalle Randalu (born 1956) Estonian pianist

- Alexander Leonidovich Goldstein (1957–2006) a Russian writer and essayist, resident of Tel-Aviv from 1991

- Peeter Järvelaid (born 1957) Estonian legal scholar, historian and professor in the University of Tallinn

- Doris Kareva (born 1958) Estonian poet and translator, head of the Estonian National Commission in UNESCO

- Anu Lamp (born 1958) Estonian stage, film, TV and voice actress, stage director, translator and instructor.

- Tõnu Õnnepalu (born 1962), also known by the pen names Emil Tode and Anton Nigov, is an Estonian poet and author

- Tõnis Lukas (born 1962) Estonian politician, Vice-Chairman of the Union of Pro Patria and Res Publica

- Marina Kaljurand (born 1962) Estonian politician who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Kiiri Tamm (born 1962) Estonian stage, television and film actress and stage manager.

- Tõnu Trubetsky (born 1963), Estonian punk rock/glam punk musician, film and music video director and individualist anarchist

- Ivo Uukkivi (born 1965) Estonian stage, film, radio, TV actor and producer, founder and singer with the punk band Velikije Luki

- Liina Tennosaar (born 1965) Estonian stage, film and television actress

- Juhan Parts (born 1966) Estonian politician and Prime Minister of Estonia from 2003 to 2005

- Mart Sander (born 1967) Estonian singer, actor, director, author, artist, and television host.

- Indrek Sirel (born 1970) general of the Estonian Defence Forces

1970 to Date

- Jaan Tallinn (born 1972) Estonian programmer, investor, and entrepreneur known for involvement in Skype and other projects.

- Jan Uuspõld (born 1973) Estonian stage, television, radio and film actor and musician.

- Urmas Paet (born 1974) Estonian politician and Member of the European Parliament

- Ken-Marti Vaher (born 1974) Estonian politician, Minister of Justice 2003–2005 and Minister of the Interior 2011–2014

- Urmas Reinsalu (born 1975) Estonian politician, Minister of Defence from 2012 to 2014, Minister of Justice since 2015

- Kristen Michal (born 1975) Estonian politician, Minister of economic affairs 2015 to 2016 and Minister of Justice from 2011 to 2012

- Mailis Reps (born 1975) Estonian politician, Minister of Education and Research 2002/03 and 2005/07

- Harriet Toompere (born 1975) Estonian stage, television, film actress and author of two children's books

- Tanel Ingi (born 1976) Estonian stage and film actor, performs primarily at the Ugala theatre

- Katrin Pärn (born 1977) Estonian stage, film and television actress and singer.

- Johann Urb (born 1977) Estonian-born American actor, producer and former model

- Carmen Kass (born 1978) Estonian model, chess player and former political candidate

- Lauri Lagle (born 1981) Estonian stage and film actor, screenwriter and stage producer, director and playwright

- Ursula Ratasepp (born 1982) Estonian stage, film and television actress.

- Ott Sepp (born 1982) Estonian actor, singer, writer and television presenter

- Katrin Siska (born 1983) Estonian musician, member of pop-rock band Vanilla Ninja

- Priit Loog (born 1984) Estonian stage, television and film actor

- Diana Arno (born 1984) Estonian beauty queen, fashion designer, model and Miss Estonia 2009

- Tiiu Kuik (born 1987) Estonian fashion model, has a mole on her left cheek

- Pääru Oja (born 1989) Estonian stage, film, voice, and television actor.

- Kristina Karjalainen (born 1989) Estonian-Finnish beauty queen who won Eesti Miss Estonia 2013

- Klaudia Tiitsmaa (born 1990) Estonian stage, television and film actress

- Natalie Korneitsik (born 1990) Estonian beauty queen, who won the title of Miss Tallinn 2012

Architects and Conductors

- Valve Pormeister (1922–2002) Estonian architect, the first women to influence the development of Estonian architecture

- Allan Murdmaa (1934–2009) Estonian architect, designed Tehumardi war memorial

- Neeme Järvi (born 1937) Estonian conductor, emigrated to the United States in 1980

- Eri Klas (1939–2016) Estonian conductor worked for the Netherlands Radio Symphony Orchestra

- Tõnu Kaljuste (born 1953) Estonian conductor, conducted with the Estonian National Opera between 1978 and 1995

- Andres Mustonen (born 1953) Estonian conductor and violinist, artistic director of Mustonenfest Tallinn Tel Aviv Festival

- Andres Siim (born 1962) Estonian architect, designed the Nissan Center in Tallinn

- Paavo Järvi (born 1962) Estonian conductor, son of Neeme Järvi

- Margit Mutso (born 1966) Estonian architect, designed the bus station of Rakvere

- Elmo Tiisvald (born 1967) Estonian conductor, conductor of Opera Studio at Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre

- Kaisa Roose (born 1969) music conductor, from 2000 with Malmö Opera and Music Theatre in Sweden

- Siiri Vallner (born 1972) Estonian architect, designed the Museum of Occupations in Tallinn

- Anu Tali (born 1972) Estonian conductor, music director of the Sarasota Orchestra

- Eero Endjärv (born 1973) Estonian architect, designed the villa in Otepää in Southern Estonia

- Katrin Koov (born 1973) Estonian architect, designed the Concert Hall of Pärnu

- Mikk Murdvee (born 1980) Estonian-Finnish conductor and violinist, lives in Helsinki.

Sport

- Albert Kusnets (1902–1942) middleweight Greco-Roman wrestler, competed in the 1924 and 1928 Summer Olympics

- Valter Palm (1905–1994) Estonian welterweight professional boxer, competed in 1924 and 1928 Summer Olympics

- Toomas Krõm (born 1971) former professional footballer, 11 caps for the Estonia national football team

- Gert Kullamäe (born 1971) retired Estonian professional basketball player

- Toomas Kallaste (born 1971) former professional footballer, 42 international caps for the Estonia national football team

- Indrek Pertelson (born 1971) Estonian judoka, won bronze at the 2000 and 2004 Summer Olympics

- Mart Poom (born 1972) Estonian football coach and former pro player, now goalkeeping coach of the Estonia national football team

- Martin Müürsepp (born 1974) Estonian retired professional basketball player and a coach

- Sergei Pareiko (born 1977) Estonian goalkeeper, 65 appearances for the Estonia national football team

- Andres Oper (born 1977) Estonian football coach, former professional player, assistant manager of the Estonia national football team

- Kristen Viikmäe (born 1979) retired Estonian footballer, played in the Estonian Meistriliiga for JK Nõmme Kalju

- Joel Lindpere (born 1981) retired Estonian professional footballer, made 107 appearances for the Estonia national football team

- Anett Kontaveit (born 1995) professional tennis player, winner of the 2017 Ricoh Open

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Tallinn participates in international town twinning schemes to foster good international relations. Partners include:[101]

Image gallery

St. Catherine's Passage

St. Catherine's Passage- St. Nicholas' Church

St Mary's Cathedral

St Mary's Cathedral Alexander Nevsky Cathedral built in 1894–1900.

Alexander Nevsky Cathedral built in 1894–1900.

Viru Gate, entrance to the Old Town. Two remaining towers that were once part of a larger fourteenth-century gate system

Viru Gate, entrance to the Old Town. Two remaining towers that were once part of a larger fourteenth-century gate system- The Raeapteek, built in 1422, is one of the oldest continuously running pharmacies in Europe

Kiek in de Kök defence tower

Kiek in de Kök defence tower Part of Lower Town city wall.

Part of Lower Town city wall.- City wall with temporary garden exhibition

- The Fat Margaret cannon tower

- Pikk Hermann (Toompea)

The ruins of Pirita Convent

The ruins of Pirita Convent

See also

References

- "Population, 1 January by Year, County, Sex and Age group". Statistics Estonia. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- "Tallinna elanike arv". Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "Gross domestic product by county (ESA 2010)". Statistics Estonia.

- "Tal•linn". Dictionary.infoplease.com. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Definition of Tallinn". Encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Tallinn – TheFreeDictionary.com.

- "Tallinn on noorem, kui õpikus kirjas!". Delfi. 28 October 2003. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- "Villu Kadakas: pringlikütid Vabaduse väljakul".

- "Historic Centre (Old Town) of Tallinn". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 7 December 1997. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Rooney, Ben (14 June 2012). "The Many Reasons Estonia Is a Tech Start-Up Nation". The Wall Street Journal.

- Germany, SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg. "Start-ups in Tallinn: Estland, das Silicon Valley Europas? – SPIEGEL ONLINE – Netzwelt". Der Spiegel.

- Ingrid Teesalu. "It's Official: Tallinn To Become EU's IT Headquarters". ERR. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "Tech capitals of the world". The Age. 15 May 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Fasman, The Geographer's Library, pp.17

- Ertl, Alan (2008). Toward an Understanding of Europe. Universal-Publishers. p. 381. ISBN 978-1-59942-983-0.

- Birnbaum, Stephen; Mayes Birnbaum, Alexandra (1992). Birnbaum's Eastern Europe. Google Books search for 'who called the settlement Kolyvan'. Harper Perennial. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-06-278019-5.

- Fasman, Jon (2006). The Geographer's Library. Penguin. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-14-303662-3.

- "A glance at the history and geology of Tallinn" by Jaak Nõlvak. In Wogogob 2004: Conference Materials

- Terras, Victor (1990). Handbook of Russian Literature. Yale University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-300-04868-1.

- The Esthonian Review. University of California. 1919.

- Tarvel, Enn (2016). "Chapter 14: Genesis of the Livonian town in the 13th century". In Murray, Alan (ed.). The North-Eastern Frontiers of Medieval Europe. Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-409-43680-5.

- Ammas, Anneli (18 January 2003). "Pealinna esmamainimise aeg kahtluse all". Eesti Päevaleht. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- "Miks ei usu ajaloolased Tallinna esmamainimisse 1154. aastal?". Horisont. 2003. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- (in Danish)In 1219 Valdemar II of Denmark, leading the Danish fleet in connection with the Livonian Crusade, landed in an Estonian town of Lindanisse

- "Salmonsens Konversations Leksikon". Runeberg.org. 19 January 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- (in German) Reval's ältester Estnischer Name Lindanisse, Verhandlungen der gelehrten estnischen Gesellschaft zu Dorpat. Band 3, Heft 1. Dorpat 1854, p. 46–47

- VIRKKUNEN, A. H. (1907). ITÄMEREN SUOMALAISET SAKSALAISEN VALLOITUKSEN AIKANA (in Finnish). Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys. p. 91.

- Singer, Nat A.; Steve Roman (2008). Tallinn in Your Pocket. In Your Pocket. p. 11. ISBN 0-01-406269-0.

- Decisions of the United States Geographic Board. United States Geographic Board. 1908.

- Young, Jekaterina (1990). Russian at Your Fingertips. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 0-415-02930-9.

- "Diccionario panhispánico de dudas | Real Academia Española". lema.rae.es.

- Alas, Askur. "The mystery of Tallinn's Central Square" (in Estonian). EE. Archived from the original on 5 November 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- "June, 9 in history – Russiapedia". Russia: RT. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "The Jewish Community of Tallinn". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Tallinn Annual Report 2011. Tallinn City Office. p. 41.

- Vaher, Rein; Miindel, Avo; Raukas, Anto; Tavast, Elvi (2010). "Ancient buried valleys in the city of Tallinn and adjacent area" (PDF). Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences. 59 (1): 37–48. doi:10.3176/earth.2010.1.03.

- Peel, M. C. and Finlayson, B. L. and McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Погода и Климат – Климат Таллина". Pogoda.ru.net. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "Climatological Information for Tallinn, Estonia". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Sunrise and Sunset in Tallinn". Time and Date. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- "Sunrise and Sunset in Tallinn". Time and Date. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- "Climate normals-Temperature". Estonian Weather Service. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- "Climate normals-Precipitation". Estonian Weather Service. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- "Climate normals-Humidity". Estonian Weather Service. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- "Climate normals-Sunshine". Estonian Weather Service. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- d.o.o, Yu Media Group. "Tallinn, Estonia – Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- "Tallinna elanike arv" [Number of Tallinn residents] (in Estonian). Tallinn city government. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Tallinn City Government (2016). Statistical Yearbook of Tallinn 2016 (PDF). Tallinn: Tallinn City Office. p. 35/194. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- "01.01.2015". Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- "POPULATION, 1 JANUARY by Sex, County, Ethnic nationality and Year". pub.stat.ee.

- Eurostat (2004). Regions: Statistical yearbook 2004 (PDF). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. p. 115/135. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2010.

- "Tallinn arvudes / Statistical Yearbook of Tallinn" (in Estonian and English). Tallinn City Council. 3 August 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Kaja Koovit. "Half of Estonian GDP is created in Tallinn". Balticbusinessnews.com. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Half of the gross domestic product of Estonia is created in Tallinn". Estonian Statistics Office. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Mark Ländler, "The Baltic Life: Hot Technology for Chilly Streets" Archived 5 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 13 December 2005.

- Anthony Ha, "GameFounders: An Accelerator For European Game Startups", Techcrunch, 21 June 2012.

- "Tallinn investing to enhance customer experience and business and operational opportunities". Airport Business. ACI EUROPE. 17 October 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Arumäe, Liisu (9 August 2013). "Tallinnas suureneb Vene ja Aasia turistide arv". E24 Majandus (in Estonian). Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "Tänavune kruiisihooaeg tõi Tallinna esmakordselt üle poole miljoni reisija" (in Estonian). Port of Tallinn. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- A study on the EU oil shale industry viewed in the light of the Estonian experience. A report by EASAC to the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy of the European Parliament (PDF) (Report). European Academies Science Advisory Council. May 2007. pp. 12–13, 18–19, 23–24, 28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "CoinMetro License". Estonian Government. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- "DX licenses" (in English and Estonian). Estonian Government. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "History | Tallinna Sadam". Portoftallinn.com. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- "Reyktal AS fleet". Archived from the original on 18 June 2010.

- "MARKTBEAT shopping centre development report" (PDF). Cushman & Wakefield. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "Regulation 1077/2011 establishing a European Agency for the operational management of large-scale IT systems in the area of freedom, security and justice". Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- "DGs – Home Affairs – What we do – Agencies". European Commission. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- "Skype Jobs: Life at Skype". Jobs.skype.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- Steve Roman. "TeliaSonera Opens IT Development Center in Tallinn". ERR. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Vahemäe, Heleri (13 September 2013). "Kuehne + Nagel joined ITL". E24 Majandus. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Schieler, Nicole (11 February 2016). "arvato Financial Solutions opens global IT Development and Innovation centre in Tallinn". arvato. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- "Ericsson Eesti planning to invest EUR 6.4 mln > Tallinn". Tallinn.ee. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- Raivo Sormunen. "aripaev.ee – Skandinaavia uue börsifirma finantskeskus tuleb Tall". Ap3.ee. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- "Tallinn Sightseeing, Museums & Attractions". Tallinn. n.d. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "ESTONIAN HISTORY MUSEUM". Eesti Asaloomuuseum. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Estonian History Museum – Great Guild Hall". Tallinn. n.d. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Estonian Maritime Museum – Fat Margaret's Tower". Tallinn. n.d. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Tallinna Lunnamuuseum". Lunnamuuseum.ee. n.d. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "ABOUT THE MUSEUM". linnamuuseum.ee. n.d. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Museum of Occupations". Visitestonia.com. n.d. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Hotel Viru & KGB Museum". Visittallinn.ee. n.d. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Estonian Museum of Natural History". Visittallinn.ee. n.d. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Estonian Health Care Museum". Visitestonia.com. n.d. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "Kumu – Art lives here!". Kumu.ekm.ee. n.d. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "About the museum". Kadriorumuuseum.ekm.ee. n.d. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design". Etdm.ee. n.d. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "Museum of Estonian Drinking Culture". Visittallinn.ee. n.d. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- Estonian Song and Dance Celebrations Estonian Song and Dance Celebration Foundation

- "Lauluväljakul oli teisel kontserdil 110 000 inimest". Delfi.

- "Estonia – Estonia is a place for independent minds". estonia.ee. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Zunes, Stephen (April 2009). "Estonia's Singing Revolution (1986–1991)". International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- "Raekoja platsil valmib maailma pikim kiluvõileib". Tallinn. Postimees (in Estonian). 14 May 2014. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "Martsipani ajalugu". kohvikmaiasmokk.ee (in Estonian). AS Kalev. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Gendlin, Vladimir; Shaposhnikov, Vasily (19 May 2003). "Estonia // SPRATS IN LIQUEUR". Kommersant. Moscow. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "Estonia saab sünnipäevaks martsipanist teatrimaja". Tallinn. Postimees (in Estonian). 10 October 2012. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "Kuidas vaeste lesknaiste toidust sai Tallinna sümbol". Tarbija24. Postimees (in Estonian). 25 February 2013. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Willsher, Kim (15 October 2018). "'I leave the car at home': how free buses are revolutionising one French city". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Copterline web page Archived 18 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 11 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Copterline läks taas pankrotti". Postimees. 11 March 2016.

- Tallinn City Council. "Tallinn Facts & Figures" (PDF). Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- "Harju County, Estonia – Maryland Sister States". Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Tallinn City Council. "Sõlmiti koostöökokkulepe Tallinna Kesklinna Valitsuse ja Carcassonne'i linna vahel". Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- Go Chengdu. "Sister Cities of Chengdu". Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- "Dartford, Tallinn's twin town". citypaper.lv.

- "Twin towns".

- "Twin Towns – Graz Online – English Version". graz.at. Archived from the original on 8 November 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- "Groningen – Partner Cities". 2008 Gemeente Groningen, Kreupelstraat 1,9712 HW Groningen. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- Hassinen, Raino. "Kotka – International co-operation: Twin Cities". City of Kotka. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- "Vänorter" (in Swedish). Malmö stad. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- "Twin cities of Riga". Riga City Council. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

Bibliography

Books and articles

- Burch, Stuart. "An unfolding signifier: London's Baltic exchange in Tallinn." Journal of Baltic Studies 39.4 (2008): 451-473.

- Hallas, Karin, ed.20th Century Architecture in Tallinn (Tallinn, The Museum of Estonian Architecture, 2000)

- Helemäe, Karl. Tallinn, Olympic Regatta city. ASIN B0006E5Y24.

- Kattago, Siobhan. "War memorials and the politics of memory: The Soviet war memorial in Tallinn." Constellations 16.1 (2009): 150-166. online

- Naum, Magdalena. "Multi-ethnicity and material exchanges in Late Medieval Tallinn." European Journal of Archaeology 17.4 (2014): 656-677. online

- Õunapuu, Piret. "The Tallinn department of the Estonian National museum: History and developments." Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore 48 (2011): 163-196.

- Pullat, Raimo. Brief history of Tallinn (Estopol, 1999).

- Tannu, Elena. The living past of Tallinn. ISBN 5-7979-0031-9.

Travel guides

- Clare Thomson. Tallinn. Footprint Publishing. ISBN 1-904777-77-5.

- Neil Taylor. Tallinn. Bradt City Guide. ISBN 1-84162-096-3.

- Dmitri Bruns. Architectural Landmarks, Places of Interest. ASIN B0006E6P9K.

- Sulev Maèvali. Historical and architectural monuments in Tallinn. ASIN B0007AUR60.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tallinn. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tallinn. |

.png)

.jpg)