Winter solstice

The winter solstice, hiemal solstice or hibernal solstice, also known as midwinter, occurs when one of the Earth's poles has its maximum tilt away from the Sun. It happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere (Northern and Southern). For that hemisphere, the winter solstice is the day with the shortest period of daylight and longest night of the year, when the Sun is at its lowest daily maximum elevation in the sky.[3] At the pole, there is continuous darkness or twilight around the winter solstice. Its opposite is the summer solstice.

| event | equinox | solstice | equinox | solstice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| month | March | June | September | December | ||||

| year | ||||||||

| day | time | day | time | day | time | day | time | |

| 2015 | 20 | 22:45 | 21 | 16:38 | 23 | 08:20 | 22 | 04:48 |

| 2016 | 20 | 04:31 | 20 | 22:35 | 22 | 14:21 | 21 | 10:45 |

| 2017 | 20 | 10:29 | 21 | 04:25 | 22 | 20:02 | 21 | 16:29 |

| 2018 | 20 | 16:15 | 21 | 10:07 | 23 | 01:54 | 21 | 22:22 |

| 2019 | 20 | 21:58 | 21 | 15:54 | 23 | 07:50 | 22 | 04:19 |

| 2020 | 20 | 03:50 | 20 | 21:43 | 22 | 13:31 | 21 | 10:03 |

| 2021 | 20 | 09:37 | 21 | 03:32 | 22 | 19:21 | 21 | 15:59 |

| 2022 | 20 | 15:33 | 21 | 09:14 | 23 | 01:04 | 21 | 21:48 |

| 2023 | 20 | 21:25 | 21 | 14:58 | 23 | 06:50 | 22 | 03:28 |

| 2024 | 20 | 03:07 | 20 | 20:51 | 22 | 12:44 | 21 | 09:20 |

| 2025 | 20 | 09:02 | 21 | 02:42 | 22 | 18:20 | 21 | 15:03 |

| Winter solstice | |

|---|---|

Lawrence Hall of Science, visitors observe sunset on the day of the winter solstice using the Sunstones II. | |

| Also called | Midwinter, Yule, the Longest Night, Jól |

| Observed by | Various cultures |

| Type | Cultural, astronomical |

| Significance | Astronomically marks the beginning of lengthening days and shortening nights |

| Celebrations | Festivals, spending time with loved ones, feasting, singing, dancing, fires |

| Date | about December 21 (NH) about June 21 (SH) |

| Frequency | Twice a year (once in the northern hemisphere, once in the southern hemisphere, six months apart) |

| Related to | Winter festivals and the solstice |

The winter solstice occurs during the hemisphere's winter. In the Northern Hemisphere, this is the December solstice (usually 21 or 22 December) and in the Southern Hemisphere, this is the June solstice (usually 20 or 21 June). Although the winter solstice itself lasts only a moment, the term sometimes refers to the day on which it occurs. Other names are "midwinter", the "extreme of winter" (Dongzhi), or the "shortest day". Traditionally, in many temperate regions, the winter solstice is seen as the middle of winter, but today in some countries and calendars, it is seen as the beginning of winter. In meteorology, winter is reckoned as beginning about three weeks before the winter solstice.[4]

Since prehistory, the winter solstice has been seen as a significant time of year in many cultures, and has been marked by festivals and rituals.[5] It marked the symbolic death and rebirth of the Sun.[6][7][8] The seasonal significance of the winter solstice is in the reversal of the gradual lengthening of nights and shortening of days.

History and cultural significance

The solstice may have been a special moment of the annual cycle for some cultures even during neolithic times. Astronomical events were often used to guide activities, such as the mating of animals, the sowing of crops and the monitoring of winter reserves of food. Many cultural mythologies and traditions are derived from this.

This is attested by physical remains in the layouts of late Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeological sites, such as Stonehenge in England and Newgrange in Ireland. The primary axes of both of these monuments seem to have been carefully aligned on a sight-line pointing to the winter solstice sunrise (Newgrange) and the winter solstice sunset (Stonehenge). It is significant that at Stonehenge the Great Trilithon was oriented outwards from the middle of the monument, i.e. its smooth flat face was turned towards the midwinter Sun.[9]

The winter solstice was immensely important because the people were economically dependent on monitoring the progress of the seasons. Starvation was common during the first months of the winter, January to April (northern hemisphere) or July to October (southern hemisphere), also known as "the famine months". In temperate climates, the midwinter festival was the last feast celebration, before deep winter began. Most cattle were slaughtered so they would not have to be fed during the winter, so it was almost the only time of year when a plentiful supply of fresh meat was available.[10] The majority of wine and beer made during the year was finally fermented and ready for drinking at this time. The concentration of the observances were not always on the day commencing at midnight or at dawn, but at the beginning of the pagan day, which in many cultures fell on the previous eve.

Because the event was seen as the reversal of the Sun's ebbing presence in the sky, concepts of the birth or rebirth of sun gods have been common. In cultures which used cyclic calendars based on the winter solstice, the "year as reborn" was celebrated with reference to life-death-rebirth deities or "new beginnings" such as Hogmanay's redding, a New Year cleaning tradition. Also "reversal" is yet another frequent theme, as in Saturnalia's slave and master reversals.

Indian

Makara Sankranti, also known as Makaraa Sankrānti (Sanskrit: मकर संक्रांति) or Maghi, is a festival day in the Hindu calendar, in reference to deity Surya (sun). It is observed each year in January.[11] It marks the first day of Sun's transit into Makara (Capricorn), marking the end of the month with the winter solstice and the start of longer days.[11][12]

Iranian

Iranian people celebrate the night of the Northern Hemisphere's winter solstice as, "Yalda night", which is known to be the "longest and darkest night of the year". Yalda night celebration, or as some call it "Shabe Chelleh" ("the 40th night"), is one the oldest Iranian traditions that has been present in Persian culture from the ancient years. In this night all the family gather together, usually at the house of the eldest, and celebrate it by eating, drinking and reciting poetry (esp. Hafez). Nuts, pomegranates and watermelons are particularly served during this festival.

Germanic

The pagan Scandinavian and Germanic people of northern Europe celebrated a winter holiday called Yule (also called Jul, Julblot, jólablót). The Heimskringla, written in the 13th century by the Icelander Snorri Sturluson, describes a Yule feast hosted by the Norwegian king Haakon the Good (c. 920–961). According to Snorri, the Christian Haakon had moved Yule from "midwinter" and aligned it with the Christian Christmas celebration. Historically, this has made some scholars believe that Yule originally was a sun festival on the winter solstice. Modern scholars generally do not believe this, as midwinter in medieval Iceland was a date about four weeks after the solstice.[13]

Roman cult of Sol

Sol Invictus ("The Unconquered Sun/Invincible Sun") was originally a Syrian god who was later adopted as the chief god of the Roman Empire under Emperor Aurelian.[14] His holiday is traditionally celebrated on December 25, as are several gods associated with the winter solstice in many pagan traditions.[15] It has been speculated to be the reason behind Christmas' proximity to the solstice.[16]

East Asian

In East Asia, the winter solstice has been celebrated as one of the Twenty-four Solar Terms, called Dongzhi in Chinese. In Japan, in order not to catch cold in the winter, there is a custom to soak oneself in a yuzu hot bath (Japanese: 柚子湯 = Yuzuyu).[17] In India, this occasion, known as Ayan Parivartan (Sanskrit: अयन परिवर्तन), is celebrated by religious Hindus as a holy day, with Hindus performing customs such as bathing in holy rivers, giving alms and donations, and praying to God and doing other holy deeds.

Observations

Although the instant of the solstice can be calculated,[18] direct observation of the solstice by amateurs is impossible because the sun moves too slowly or appears to stand still (the meaning of "solstice"). However, by use of astronomical data tracking, the precise timing of its occurrence is now public knowledge. One cannot directly detect the precise instant of the solstice (by definition, one cannot observe that an object has stopped moving until one later observes that it has not moved further from the preceding spot, or that it has moved in the opposite direction). Furthermore, to be precise to a single day, one must be able to observe a change in azimuth or elevation less than or equal to about 1/60 of the angular diameter of the Sun. Observing that it occurred within a two-day period is easier, requiring an observation precision of only about 1/16 of the angular diameter of the Sun. Thus, many observations are of the day of the solstice rather than the instant. This is often done by observing sunrise and sunset or using an astronomically aligned instrument that allows a ray of light to be cast on a certain point around that time. The earliest sunset and latest sunrise dates differ from winter solstice, however, and these depend on latitude, due to the variation in the solar day throughout the year caused by the Earth's elliptical orbit (see earliest and latest sunrise and sunset).

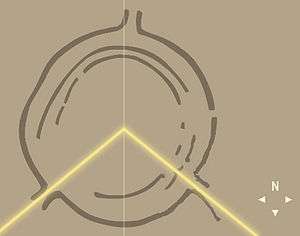

Neolithic site of Goseck circle. The yellow lines indicate the directions in which sunrise and sunset are seen on the day of the winter solstice.

Neolithic site of Goseck circle. The yellow lines indicate the directions in which sunrise and sunset are seen on the day of the winter solstice. Sunrise at Stonehenge on the winter solstice

Sunrise at Stonehenge on the winter solstice

Holidays celebrated on the winter solstice

- Alban Arthan (Welsh)

- Blue Christmas (holiday) (Western Christian)

- Brumalia (Ancient Rome)

- Dongzhi Festival (East Asia)

- Korochun (Slavic)

- Sanghamitta Day (Theravada Buddhism)

- Shalako (Zuni)

- Yaldā (Iran)

- Yule in the Northern Hemisphere (Neopagan)

- Ziemassvētki (ancient Latvia)

Other related festivals

- Saturnalia (Ancient Rome): Celebrated shortly before winter solstice

- Saint Lucy's Day (Christian): Used to coincide with the winter solstice day

- Christmas: Takes place shortly after winter solstice, absorbed tradition from winter solstice celebration. Speculated to originate from solstice date, see Christmas#Solstice date and Dies Natalis Solis Invicti

- Cold Food Festival (Korea, Greater China): 105 days after winter solstice

- Makar Sankranti / Pongal (India): Harvest Festival - Marks the end of the cold months and start of the new Month with longer days.

Length of the day near the northern winter solstice

The following tables contain information on the length of the day on December 22nd, close to the winter solstice of the Northern Hemisphere and the summer solstice of the Southern Hemisphere (i.e. December solstice). The data was collected from the website of the Finnish Meteorological Institute on 22 December 2015, as well as from certain other websites.[19][20][21][22][23]

The data is arranged geographically and within the tables from the shortest day to the longest one.

| The Nordic countries and the Baltic states | |||

| City | Sunrise 22 Dec 2015 |

Sunset 22 Dec 2015 |

Length of the day |

|---|---|---|---|

| Murmansk | — | — | 0 h |

| Bodø | 11:36 | 12:25 | 0 h 49 min |

| Rovaniemi | 11:08 | 13:22 | 2 h 14 min |

| Luleå | 9:55 | 13:04 | 3 h 08 min |

| Reykjavík | 11:22 | 15:29 | 4 h 07 min |

| Trondheim | 10:01 | 14:31 | 4 h 30 min |

| Tórshavn | 9:51 | 14:59 | 5 h 08 min |

| Helsinki | 9:24 | 15:13 | 5 h 49 min |

| Oslo | 9:18 | 15:12 | 5 h 54 min |

| Tallinn | 9:17 | 15:20 | 6 h 02 min |

| Stockholm | 8:43 | 14:48 | 6 h 04 min |

| Riga | 9:00 | 15:43 | 6 h 43 min |

| Copenhagen | 8:37 | 15:38 | 7 h 01 min |

| Vilnius | 8:40 | 15:54 | 7 h 14 min |

| Europe | |||

| City | Sunrise 22 Dec 2015 |

Sunset 22 Dec 2015 |

Length of the day |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh | 8:42 | 15:40 | 6 h 57 min |

| Moscow | 8:57 | 15:58 | 7 h 00 min |

| Berlin | 8:15 | 15:54 | 7 h 39 min |

| Warsaw | 7:43 | 15:25 | 7 h 42 min |

| London | 8:04 | 15:53 | 7 h 49 min |

| Kiev | 7:56 | 15:56 | 8 h 00 min |

| Paris | 8:41 | 16:56 | 8 h 14 min |

| Vienna | 7:42 | 16:03 | 8 h 20 min |

| Budapest | 7:28 | 15:55 | 8 h 26 min |

| Rome | 7:34 | 16:42 | 9 h 07 min |

| Madrid | 8:34 | 17:51 | 9 h 17 min |

| Lisbon | 7:51 | 17:18 | 9 h 27 min |

| Athens | 7:37 | 17:09 | 9 h 31 min |

| Africa | |||

| City | Sunrise 22 Dec 2015 |

Sunset 22 Dec 2015 |

Length of the day |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cairo | 6:47 | 16:59 | 10 h 12 min |

| Tenerife | 7:53 | 18:13 | 10 h 19 min |

| Dakar | 7:30 | 18:46 | 11 h 15 min |

| Addis Ababa | 6:35 | 18:11 | 11 h 36 min |

| Nairobi | 6:25 | 18:37 | 12 h 11 min |

| Kinshasa | 5:45 | 18:08 | 12 h 22 min |

| Dar es Salaam | 6:05 | 18:36 | 12 h 31 min |

| Luanda | 5:46 | 18:24 | 12 h 38 min |

| Antananarivo | 5:10 | 18:26 | 13 h 16 min |

| Windhoek | 6:04 | 19:35 | 13 h 31 min |

| Johannesburg | 5:12 | 18:59 | 13 h 47 min |

| Cape Town | 5:32 | 19:57 | 14 h 25 min |

| Americas | |||

| City | Sunrise 22 Dec 2015 |

Sunset 22 Dec 2015 |

Length of the day |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fairbanks | 10:58 | 14:40 | 3 h 41 min |

| Nuuk | 10:22 | 14:28 | 4 h 06 min |

| Anchorage | 10:14 | 15:42 | 5 h 27 min |

| Edmonton | 8:48 | 16:15 | 7 h 27 min |

| Vancouver | 8:05 | 16:16 | 8 h 11 min |

| Seattle | 7:55 | 16:20 | 8 h 25 min |

| Ottawa | 7:39 | 16:22 | 8 h 42 min |

| Toronto | 7:48 | 16:43 | 8 h 55 min |

| New York City | 7:16 | 16:32 | 9 h 15 min |

| Washington, D.C. | 7:23 | 16:49 | 9 h 26 min |

| Los Angeles | 6:55 | 16:48 | 9 h 53 min |

| Dallas | 7:25 | 17:25 | 9 h 59 min |

| Miami | 7:03 | 17:35 | 10 h 31 min |

| Honolulu | 7:04 | 17:55 | 10 h 50 min |

| Mexico City | 7:06 | 18:03 | 10 h 57 min |

| Managua | 6:01 | 17:26 | 11 h 24 min |

| Bogotá | 5:59 | 17:50 | 11 h 51 min |

| Quito | 6:08 | 18:16 | 12 h 08 min |

| Recife | 5:00 | 17:35 | 12 h 35 min |

| Lima | 5:41 | 18:31 | 12 h 50 min |

| La Paz | 5:57 | 19:04 | 13 h 06 min |

| Rio de Janeiro | 6:04 | 19:37 | 13 h 33 min |

| São Paulo | 6:17 | 19:52 | 13 h 35 min |

| Porto Alegre | 6:20 | 20:25 | 14 h 05 min |

| Santiago | 6:29 | 20:52 | 14 h 22 min |

| Buenos Aires | 5:37 | 20:06 | 14 h 28 min |

| Ushuaia | 4:51 | 22:11 | 17 h 19 min |

| Asia and Oceania | |||

| City | Sunrise 22 Dec 2015 |

Sunset 22 Dec 2015 |

Length of the day |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magadan | 8:54 | 14:55 | 6 h 00 min |

| Petropavlovsk | 9:36 | 17:10 | 7 h 33 min |

| Khabarovsk | 8:48 | 17:07 | 8 h 18 min |

| Ulaanbaatar | 8:39 | 17:02 | 8 h 22 min |

| Vladivostok | 8:40 | 17:40 | 8 h 59 min |

| Beijing | 7:32 | 16:52 | 9 h 20 min |

| Seoul | 7:44 | 17:17 | 9 h 34 min |

| Tokyo | 6:47 | 16:31 | 9 h 44 min |

| Shanghai | 6:48 | 16:55 | 10 h 07 min |

| Lhasa | 8:46 | 19:01 | 10 h 14 min |

| Delhi | 7:09 | 17:28 | 10 h 19 min |

| Hong Kong | 6:58 | 17:44 | 10 h 46 min |

| Manila | 6:16 | 17:32 | 11 h 15 min |

| Bangkok | 6:36 | 17:55 | 11 h 19 min |

| Singapore | 7:01 | 19:04 | 12 h 03 min |

| Jakarta | 5:36 | 18:05 | 12 h 28 min |

| Denpasar | 5:58 | 18:36 | 12 h 37 min |

| Darwin | 6:19 | 19:10 | 12 h 51 min |

| Papeete | 5:21 | 18:32 | 13 h 10 min |

| Brisbane | 4:49 | 18:42 | 13 h 52 min |

| Perth | 5:07 | 19:22 | 14 h 14 min |

| Sydney | 5:41 | 20:05 | 14 h 24 min |

| Auckland | 5:58 | 20:39 | 14 h 41 min |

| Melbourne | 5:54 | 20:42 | 14 h 47 min |

| Invercargill | 5:50 | 21:39 | 15 h 48 min |

Length of day increases from the equator towards the South Pole in the Southern Hemisphere in December (around the summer solstice there), but decreases towards the North Pole in the Northern Hemisphere at the time of the northern winter solstice.

See also

- Dongzhi

- Burning the Clocks

- Christmas in July

- December solstice

- Effect of sun angle on climate

- Equinox

- Festival of Lights (disambiguation)

- Festive ecology

- Festivus

- Halcyon days

- Hanukkah

- HumanLight

- June solstice

- Koliada

- Kwanzaa

- Lohri

- Makar Sankranti

- Midsummer

- Summer solstice

- Thai Pongal

- Tekufah

- Tiregān

- Yaldā Night

References

- United States Naval Observatory (January 4, 2018). "Earth's Seasons and Apsides: Equinoxes, Solstices, Perihelion, and Aphelion". Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- "Solstices and Equinoxes: 2001 to 2100". AstroPixels.com. February 20, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- Shipman, James; Wilson, Jerry D.; Todd, Aaron (2007). "Section 15.5". An Introduction to Physical Science (12th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-618-92696-1.

- "When does spring start?". Met Office. June 3, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- "Winter Solstice celebrations: a.k.a. Christmas, Saturnalia, Yule, the Long Night, start of Winter, etc". Religious Tolerance.org. August 5, 2015 [December 3, 1999].

- Krupp, E C. Echoes of the Ancient Skies: The Astronomy of Lost Civilizations. Courier Corporation, 2012. pp.119, 125, 195

- North, John. Stonehenge. The Free Press, 1996. p.530

- Hadingham, Evan. Early Man and the Cosmos. University of Oklahoma Press, 1985. p.50

- Johnson, Anthony (2008). Solving Stonehenge: The New Key to an Ancient Enigma. Thames & Hudson. pp. 252–253. ISBN 9780500051559.

- "History of Christmas". History.com. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- Kamal Kumar Tumuluru (2015). Hindu Prayers, Gods and Festivals. Partridge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4828-4707-9.

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A - M. Rosen Publishing Group. p. 411. ISBN 978-0-8239-2287-1.

- Nordberg, Andreas (2006). Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning: Kalendrar och kalendariska riter i det förkristna Norden. Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi (in Swedish). 91. Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien för svensk folkkultur. pp. 120–121. ISBN 91-85352-62-4. ISSN 0065-0897.

- Clauss, Manfred (2001). Die römischen Kaiser : 55 historische Portraits von Caesar bis Iustinian (in German). München: Beck. p. 250. ISBN 978-3-406-47288-6.

- Capoccia, Kathryn (2002). "Christmas Traditions". Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- Bishop Jacob Bar-Salabi (cited in Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, Ramsay MacMullen. Yale:1997, p. 155)

- Goin’ Japanesque!: Japanese Winter Solstice Traditions; A Day for Kabocha and Yuzuyu

- Meeus, Jean (2009). Astronomical Algorithms (2nd English Edition with corrections as of August 10, 2009 ed.). Richmond, Virginia: Willmann-Bell, Inc. ISBN 978-0-943396-61-3.

- "Paikallissää Helsinki" [‘Local weather in Helsinki’] (in Finnish). Finnish Meteorological Institute. 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- "Perth, Australia". Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- "São Paulo, Brazil". Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- "Denpasar, Indonesia". Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- "Edmonton, Canada". Retrieved 2019-12-21.

Further reading

- Macphail, Cameron (20 December 2015). "Winter solstice 2015: Everything you need to know about the shortest day of the year". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 December 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Handwerk, Brian (2015-12-21). "Everything You Need to Know About the Winter Solstice". National Geographic. Retrieved 2015-12-21.