Pskov Republic

Pskov (Latin: Plescoviae[1]), known at various times as the Principality of Pskov (Russian: Псковское княжество, Pskovskoye knyazhestvo) or the Pskov Republic (Russian: Псковская Республика, Pskovskaya Respublika), was a medieval state on the south shore of Lake Pskov. The capital city, also named Pskov, was located at the southern end of the Peipus–Pskov Lake system at the southeast corner of Ugandi, about 150 miles (240 km) southwest of Nevanlinna, and 100 miles (160 km) west-southwest of Great Novgorod. It was originally known as Pleskov, and is now roughly equivalent geographically to the Pskov Oblast of Russia. It was a principality ca. 862–1230, after which it was joined to the Novgorod Republic. From 1348, Pleskov became again independent from Novgorod and established an aristocratic oligarchy.

Pskov Republic Псковская Республика (Pskovskaya Respublika) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1348–1510 | |||||||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||

Eastern Europe, 1466

| |||||||||||||

| Capital | Pskov | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old East Slavic, Seto, Russian | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox Church, Estonian paganism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Mixed | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 1348 | ||||||||||||

| 1348 | |||||||||||||

1399 | |||||||||||||

| 1510 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

Origin

As a principality, Pleskov was ruled by separate princes, but often it was ruled directly from Novgorod until the mid-13th century when the city began accepting as rulers princes exiled from their possessions. Each exiled prince that went to Pleskov could be proclaimed prince there (if the principal throne wasn't already occupied by another prince). In any case, he could at least get an honorary reception and live there without fear for his life.

After the disintegration of Kievan Rus' in the 12th century, the city of Pskov with its surrounding territories along the Velikaya River, Lake Peipus, Pskovskoye Lake and Narva River became part of the Novgorod Republic. It kept its special autonomous rights, including the right for independent construction of suburbs (Izborsk is the most ancient among them). Due to Pskov's leading role in the struggle against the Livonian Order, its influence spread significantly. The long reign of Daumantas (1266–99) and especially his victory in the Battle of Rakvere (1268) ushered in the period of Pskov's actual independence. The Novgorod boyars formally recognized Pskov's independence in the Treaty of Bolotovo (1348), relinquising their right to appoint the posadniks of Pskov. The city of Pskov remained dependent on Novgorod only in ecclesiastical matters until 1589, when a separate bishopric of Pskov was created and the archbishops of Novgorod dropped Pskov from their title and were created "Archbishops of Novgorod the Great and Velikie Luki".

Internal organization

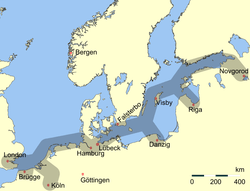

The Pskov Republic had well-developed farming, fishing, blacksmithing, jewellery-making and construction industries. Exchange of commodities within the republic itself and its trade with Novgorod and other Russian cities, the Baltic region, and Western European cities made Pskov one of the biggest handicraft and trade centers of Rus'. As opposed to the Novgorod Republic, Pskov never had big feudal landowners: estates were smaller and even more scattered than of those in Novgorod.[2] The estates of Pskovian monasteries and churches were much smaller as well.

The social relations that had taken shape in the Pskov Republic were reflected in the Legal Code of Pskov. Peculiarities of the economy, centuries-old ties with Novgorod, frontier status, and military threats led to the development of the veche (popular assembly with judicial and legislative powers) system in the Pskov Republic. The princes played a subordinate role. The veche elected posadniks and sotskiys (Russian: сотский, initially, an official who represented a hundred households) and regulated the relations between feudals, posad people, izborniks (Russian: изборник, elected officials), and smerds (peasants). The boyar (aristocrat) council had a special influence on the decisions of the veche, which gathered at the Trinity Cathedral. The latter also held the archives of the veche and important private papers and state documents. The elective offices became a privilege of several noble families. During the most dramatic moments in the history of Pskov, however, the so-called "molodshiye" posad people (Russian: молодшие посадские люди, or low-ranking posad officials) played an important and, at times, decisive role in the veche. The struggle between the boyars and smerds, "molodshiye" and "bolshiye" posad people (high-ranking posad officials) was reflected in the heresy of the Strigolniki in the 14th century and in veche debates of the 1470s to the 1490s, which often resulted in bloody clashes.

Final years

The ties with the Grand Duchy of Moscow became stronger in the final years of 14th century, after Pskov's participation in the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380. Since 1399 Pskov with its adjacent lands became a viceroyalty of Moscow with their own namestnik (viceroy) knyaz appointed by the Moscow's royalty.

Since the 15th century, several princes of the Gediminid line were prominent there too, holding high positions such as governorship (Ikonnikov, 1934). Their surnames included Golitsin, Kurakin and Khovansky.

In 1501, armies of Pskov and Moscow were defeated in the Battle of the Siritsa River by the Livonian Order, but the city withstood the subsequent siege.

In 1510, Grand Prince of Moscow Vasili III arrived in Pskov and pronounced it his votchina, thus putting an end to the Pskov Republic and its autonomous rights. The city's ruling body, the veche, was dissolved and some 300 families of rich Pskovians were deported from the city. Their estates were distributed among the Muscovite service class people. From that time on, the city of Pskov and the lands around it continued to develop as a part of the centralized Russian state, preserving some of its economic and cultural traditions.

The downfall of Pskov is recounted in the Muscovite Story of the Taking of Pskov (1510), which was lauded by D. S. Mirsky as "one of the most beautiful short stories of Old Russia. The history of the Muscovites' leisurely perseverance is told with admirable simplicity and art. An atmosphere of descending gloom pervades the whole narrative: all is useless, and whatever the Pskovites can do, the Muscovite cat will take its time and eat the mouse when and how it pleases".[3]

Princes of Pskov

- 1342 - 1349 Andrei of Polotsk (Gedeminids)

- 1349 - 1360 Eustaphy Feodorovich (Prince of Izborsk)

- 1360 - 1369 Alexander of Polotsk

- 1375 - 1377 Matvei

- 1377 - 1399 Andrei of Polotsk

- 1386 - 1394 Ivan Andreyevich

- since 1399 conquest by Grand Duchy of Muscovy

See also

- Truvor and Sineus

- False Dmitry II

- False Dmitry III

- Economy of the Pskov Republic

References

- Introduction into the Latin epigraphy (Введение в латинскую эпиграфику).

- Масленникова, Н. Н. (1978). Псковская земля // Аграрная история Северо-Запада России XVI века. Leningrad: Nauka.

- D. S. Mirsky. A History of Russian Literature. Northwestern University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8101-1679-0. Page 23.

Sources

- The Chronicles of Pskov, vol. 1–2. Moscow–Leningrad, 1941–55.

- Масленникова Н. Н. Присоединения Пскова к Русскому централизованному государству. Leningrad, 1955.

- Валеров А.В. Новгород и Псков: Очерки политической истории Северо-Западной Руси XI-XIV вв. Moscow: Aleteia, 2004. ISBN 5-89329-668-0.

- The Pskov 3rd Chronicle