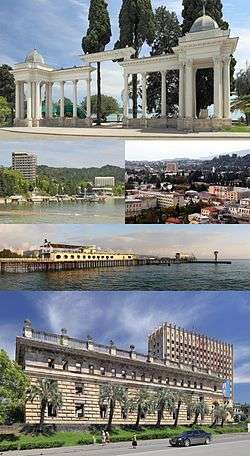

Sukhumi

Sukhumi or Sokhumi (Abkhazian: Аҟәа, Aqwa; Georgian: სოხუმი, [sɔxumi] (![]()

Sokhum Sukhumi | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

Coat of arms | |

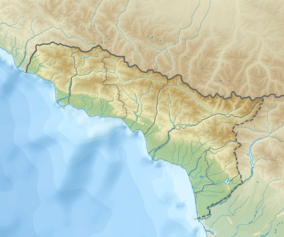

Sokhum Location of Sukhumi in Georgia  Sokhum Sokhum (Georgia) | |

| Coordinates: 43°00′12″N 41°00′55″E | |

| Country | Georgia |

| Partially recognized state | Abkhazia[1] |

| Settled | 6th century BC |

| City Status | 1848 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Adgur Kharazia |

| Area | |

| • Total | 27 km2 (10 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 140 m (460 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Total | 65,439[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK) |

| Postal code | 384900 |

| Area code | +7 840 22x-xx-xx |

| Vehicle registration | ABH |

Sukhumi's history can be traced back to the 6th century BC, when it was settled by Greeks, who named it Dioscurias. During this time and the subsequent Roman period, much of the city disappeared under the Black Sea. The city was named Tskhumi when it became part of the Kingdom of Abkhazia and then the Kingdom of Georgia. Contested by local princes, it became part of the Ottoman Empire in the 1570s, where it remained until it was conquered by the Russian Empire in 1810. Following a period of conflict during the Russian Civil War, it became part of the independent Georgia, which included Abkhazia, in 1918.[3] In 1921, the Democratic Republic of Georgia was occupied by the Soviet Bolshevik forces from Russia. Within the Soviet Union, it was regarded as a holiday resort. As the Soviet Union broke up in the early 1990s, the city suffered significant damage during the Abkhaz–Georgian conflict. The present-day population of 60,000 is only half of the population living there towards the end of Soviet rule.

Naming

In Georgian, the city is known as სოხუმი (Sokhumi) or აყუ (Aqu),[4] in Megrelian as აყუჯიხა (Aqujikha),[5] and in Russian as Сухум (Sukhum) or Сухуми (Sukhumi). The toponym Sokhumi derives from the Georgian word Tskhomi/Tskhumi, meaning beech.[6] It is significant, that "dia" in several dialects of the Georgian language and among them in Megrelian means mother and "skuri" means water.[6] In Abkhaz, the city is known as Аҟәа (Aqwa), which, according to native tradition, signifies water.[7]

The medieval Georgian sources knew the town as Tskhumi (ცხუმი).[8][9][10] Later, under the Ottoman control, the town was known in Turkish as Suhum-Kale, which can be derived from the earlier Georgian form Tskhumi or can be read to mean "water-sand fortress".[11][12] Tskhumi in turn is supposed to be derived from the Svan language word for "hot",[13] or the Georgian word for "hornbeam tree".

The ending -i in the above forms represents the Georgian nominative-suffix. The town was initially officially described in Russian as Сухум (Sukhum), until 16 August 1936 when this was changed to Сухуми (Sukhumi). This remained so until 4 December 1992, when the Supreme Council of Abkhazia restored the original version, that was approved in Russia in autumn 2008,[14] even though Сухуми is also still being used.

In English, the most common form today is Sukhumi, although Sokhumi is increasing in usage and has been adopted by sources including Encyclopædia Britannica,[15] MSN Encarta,[16] Esri[17] and Google Maps.[18]

General information

Sukhumi is located on a wide bay of the eastern coast of the Black Sea and serves as a port, rail junction and a holiday resort. It is known for its beaches, sanatoriums, mineral-water spas and semitropical climate. Sukhumi is also an important air link for Abkhazia as the Sukhumi Dranda Airport is located nearby the city. Sukhumi contains a number of small-to-medium size hotels serving chiefly the Russian tourists. Sukhumi botanical garden was established in 1840, one of the oldest botanical gardens in the Caucasus.

The city has a number of research institutes, the Abkhazian State University and the Sukhumi Open Institute. From 1945 to 1954 the city's electron physics laboratory was involved in the Soviet program to develop nuclear weapons. Additionally, the Abkhaz State Archive is located in the city.

The city is a member of the International Black Sea Club.[19]

History

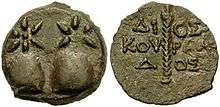

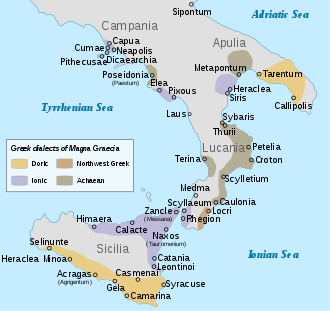

The history of the city began in the mid-6th century BC when an earlier settlement of the second and early first millennia BC, frequented by local Colchian tribes, was replaced by the Milesian Greek colony of Dioscurias (Greek: Διοσκουριάς). The city is said to have been founded[20][21] and named by the Dioscuri, the twins Castor and Pollux of classical mythology. According to another legend it was founded by Amphitus and Cercius of Sparta, the charioteers of the Dioscuri.[22][23] Arrian wrote that it was a colony of Miletus.[24]

It became busily engaged in the commerce between Greece and the indigenous tribes, importing wares from many parts of Greece, and exporting local salt and Caucasian timber, linen, and hemp. It was also a prime center of slave trade in Colchis.[25] The city and its surroundings were remarkable for the multitude of languages spoken in its bazaars.[26]

Although the sea made serious inroads upon the territory of Dioscurias, it continued to flourish until its conquest by Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontus in the later 2nd century. Under the Roman emperor Augustus the city assumed the name of Sebastopolis[27] (Greek: Σεβαστούπολις). But its prosperity was past, and in the 1st century Pliny the Elder described the place as virtually deserted though the town still continued to exist during the times of Arrian in the 130s.[28] The remains of towers and walls of Sebastopolis have been found underwater; on land the lowest levels so far reached by archaeologists are of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. According to Gregory of Nyssa there were Christians in the city in the late 4th century.[29] In 542 the Romans evacuated the town and demolished its citadel to prevent it from being captured by Sasanian Empire. In 565, however, the emperor Justinian I restored the fort and Sebastopolis continued to remain one of the Byzantine strongholds in Colchis until being sacked by the Arab conqueror Marwan II in 736.

Afterwards, the town came to be known as Tskhumi.[13] Restored by the kings of Abkhazia from the Arab devastation, it particularly flourished during the Georgian Golden Age in the 12th–13th centuries, when Tskhumi became a center of traffic with the European maritime powers, particularly with the Republic of Genoa. The Genoese established their short-lived trading factory at Tskhumi early in the 14th century. The city of Tskhumi became the summer residence of the Georgian kings. According to Russian scholar V. Sizov, it became an important “cultural and administrative center of the Georgian state.[30] Later Tskhumi served as capital of the Odishi — Megrelian rulers, it was in this city that Vamek I (c. 1384–1396), the most influential Dadiani, minted his coins.[31]

Documents of the 15th century clearly distinguished Tskhumi from Principality of Abkhazia.[32] The Ottoman navy occupied the town in 1451, but for a short time. Later contested between the princes of Abkhazia and Mingrelia, Tskhumi finally fell to the Turks in the 1570s. The new masters heavily fortified the town and called it Sohumkale, with kale meaning "fort" but the first part of the name of disputed origin. It may represent Turkish su, "water", and kum, "sand", but is more likely to be an alteration of its earlier Georgian name.[13]

At the request of the pro-Russian Abkhazian prince, the town was stormed by the Russian Marines in 1810 and turned, subsequently, into a major outpost in the North West Caucasus. (See Russian conquest of the Caucasus). Sukhumi was declared the seaport in 1847 and was directly annexed to the Russian Empire after the ruling Shervashidze princely dynasty was ousted by the Russian authorities in 1864. During the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878, the town was temporarily controlled by the Ottoman forces and Abkhaz-Adyghe rebels.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, the town and Abkhazia in general were engulfed in the chaos of the Russian Civil War. A short-lived Bolshevik government was suppressed in May 1918 and Sukhumi was incorporated into the Democratic Republic of Georgia as a residence of the autonomous People's Council of Abkhazia and the headquarters of the Georgian governor-general. The Red Army and the local revolutionaries took the city from the Georgian forces on 4 March 1921, and declared Soviet rule. Sukhumi functioned as the capital of the "Union treaty" Abkhaz Soviet Socialist Republic associated with the Georgian SSR from 1921 until 1931, when it became the capital of the Abkhazian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the Georgian SSR. By 1989, Sukhumi had 110,000 inhabitants and was one of the most prosperous cities of Georgia. Many holiday dachas for Soviet leaders were situated there.

Beginning with the 1989 riots, Sukhumi was a centre of the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, and the city was severely damaged during the 1992–1993 War. During the war, the city and its environs suffered almost daily air strikes and artillery shelling, with heavy civilian casualties.[33] On 27 September 1993 the battle for Sukhumi was concluded by a full-scale campaign of ethnic cleansing against its majority Georgian population (see Sukhumi Massacre), including members of the pro-Georgian Abkhazian government (Zhiuli Shartava, Raul Eshba and others) and mayor of Sukhumi Guram Gabiskiria. Although the city has been relatively peaceful and partially rebuilt, it is still suffering the after-effects of the war, and it has not regained its earlier ethnic diversity. Its population in 2003 was 43,716, compared to about 120,000 in 1989.[34]

Population

Demographics

Historic population figures for Sukhumi, split out by ethnicity, based on population censuses:[35]

| Year | Abkhaz | Armenians | Estonians | Georgians | Greeks | Russians | Turkish | Ukrainians | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1897 Census | 1.8% (144) |

13.5% (1,083) |

0.4% (32) |

11.9% (951) |

14.3% (1,143) |

0.0% (1) |

2.7% (216) |

7,998 | |

| 1926 Census | 3.1% (658) |

9.4% (2,023) |

0.3% (63) |

11.2% (2,425) |

10.7% (2,298) |

23.7% (5,104) |

--- | 10.4% (2,234) |

21,568 |

| 1939 Census | 5.5% (2,415) |

9.8% (4,322) |

0.5% (206) |

19.9% (8,813) |

11.3% (4,990) |

41.9% (18,580) |

--- | 4.6% (2,033) |

44,299 |

| 1959 Census | 5.6% (3,647) |

10.5% (6,783) |

--- | 31.1% (20,110) |

4.9% (3,141) |

36.8% (23,819) |

--- | 4.3% (2,756) |

64,730 |

| 1979 Census | 9.9% (10,766) |

10.9% (11,823) |

--- | 38.3% (41,507) |

6.5% (7,069) |

26.4% (28,556) |

--- | 3.4% (3,733) |

108,337 |

| 1989 Census | 12.5% (14,922) |

10.3% (12,242) |

--- | 41.5% (49,460) |

--- | 21.6% (25,739) |

--- | --- | 119,150 |

| 2003 Census | 65.3% (24,603) |

12.7% (5,565) |

0.1% (65) |

4.0% (1,761) |

1.5% (677) |

16.9% (8,902) |

--- | 1.6% (712) |

43,716 |

| 2011 Census | 67.3% (42,603 ) |

9.8% (6,192) |

--- | 2.8% (1,755) |

1.0% (645) |

14.8% (9,288) |

--- | --- | 62,914 |

Religion

Ancient Sebastopolis was a Latin bishopric, but the diocese ceased to exist with the advent of Orthodoxy.

Titular see

The diocese of Sebastopolis in Abasgia was nominally restored as a Catholic Latin.

It has had the following incumbents, but is now vacant:

- Celestino Annibale Cattaneo, Capuchin Franciscans (O.F.M. Cap.) (1936.03.03 – 1946.02.15)

- Henri-Édouard Dutoit (1949.04.23 – 1953.04.17)

- Aluigi Cossio (1955.08.12 – 1956.01.03)

- Giuseppe Paupini (1956.02.02 – 1969.04.28), later cardinal

Main sights

Sukhumi houses a number of historical monuments, notably the Besleti Bridge built during the reign of queen Tamar of Georgia in the 12th century. It also retains visible vestiges of the defunct monuments, including the Roman walls, the medieval Castle of Bagrat, several towers of the Kelasuri Wall, also known as Great Abkhazian Wall, constructed between 1628 and 1653 by Levan II Dadiani to protect his fiefdom from the Abkhaz tribes;[36] the 14th-century Genoese fort and the 18th-century Ottoman fortress. The 11th century Kamani Monastery (12 kilometres (7 miles) from Sukhumi) is erected, according to tradition, over the tomb of Saint John Chrysostom. Some 22 km (14 mi) from Sukhumi lies New Athos with the ruins of the medieval city of Anacopia. The Neo-Byzantine New Athos Monastery was constructed here in the 1880s on behest of Tsar Alexander III of Russia.

Northward in the mountains is the Krubera Cave, one of the deepest in the world, with a depth of 2,140 meters.[37]

Education

Sukhumi is a home for largest educational institutions (both higher education institutions and Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges) and largest students' community in Abkhazia.

Abkhaz State University (1979)

Sukhumi State College (1904) (from 1904 to 1921 - Sukhumi Real School; from 1921 to 1999 - Sukhumi Industrial Technical School),

Sukhumi Art College (1935),

Abkhaz Multiindustrial College (1959) (from 1959 to 1999 - Sukhumi trade and culinary school),

Climate

Sukhumi has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), that is almost cool enough in summer to be an oceanic climate.

| Climate data for Sukhumi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.0 (50.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

12.8 (55.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

18.3 (65.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.7 (36.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

10.0 (49.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 102 (4.0) |

76 (3.0) |

102 (4.0) |

102 (4.0) |

92 (3.6) |

89 (3.5) |

83 (3.3) |

107 (4.2) |

120 (4.7) |

114 (4.5) |

104 (4.1) |

108 (4.3) |

1,199 (47.2) |

| Average rainy days | 17 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 16 | 16 | 160 |

| Source 1: climatebase.ru[38] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Georgia Travel Climate Information[39] | |||||||||||||

Administration

On 2 February 2000, President Ardzinba dismissed temporary Mayor Leonid Osia and appointed Leonid Lolua in his stead.[40] Lolua was reappointed on 10 May 2001 following the March 2001 local elections.[41]

On 5 November 2004, in the heated aftermath of the 2004 presidential election, president Vladislav Ardzinba appointed head of the Gulripsh district assembly Adgur Kharazia as acting mayor. During his first speech he called upon the two leading candidates, Sergei Bagapsh and Raul Khadjimba, to both withdraw.[42]

On 16 February 2005, after his election as President, Bagapsh replaced Kharazia with Astamur Adleiba, who had been Minister for Youth, Sports, Resorts and Tourism until December 2004.[43] In the 11 February 2007 local elections, Adleiba successfully defended his seat in the Sukhumi city assembly and was thereupon reappointed mayor by Bagapsh on 20 March.[44]

In April 2007, while President Bagapsh was in Moscow for medical treatment, the results of an investigation into corruption within the Sukhumi city administration were made public. The investigation found that large sums had been embezzled and upon his return, on 2 May, Bagapsh fired Adleiba along with his deputy Boris Achba, the head of the Sukhumi's finance department Konstantin Tuzhba and the head of the housing department David Jinjolia.[45] On 4 June Adleiba paid back to the municipal budget 200,000 rubels.[46] and on 23 July, he resigned from the Sukhumi city council, citing health reasons and the need to travel abroad for medical treatment.[47]

On 15 May 2007, president Bagapsh released Alias Labakhua as First Deputy Chairman of the State Customs Committee and appointed him acting Mayor of Sukhumi, a post temporarily fulfilled by former Vice-Mayor Anzor Kortua. On 27 May Labakhua appointed Vadim Cherkezia as Deputy Chief of staff.[48] On 2 September, Labakhua won the by-election in constituency No. 21, which had become necessary after Adleiba relinquished his seat. Adleiba was the only candidate and voter turnout was 34%, higher than the 25% required.[49] Since Adleiba was now a member of the city assembly, president Bagapsh could permanently appoint him Mayor of Sukhumi on 18 September.[50]

Following the May 2014 Revolution and the election of Raul Khajimba as President, he on 22 October dismissed Labakhua and again appointed (as acting Mayor) Adgur Kharazia, who at that point was Vice Speaker of the People's Assembly.[51] Kharazia won the 4 April 2015 by-election to the City Council in constituency no. 3 unopposed,[52] and was confirmed as mayor by Khajimba on 4 May.[53]

List of Mayors

| # | Name | From | Until | President | Comments | ||

| Chairmen of the (executive committee of the) City Soviet: | |||||||

| Vladimir Mikanba | 1975 | [54] | 1985 | [54] | |||

| D. Gubaz | <=1989 | >=1989 | |||||

| Nodar Khashba | 1991 | [54] | First time | ||||

| Guram Gabiskiria | 1992 | 27 September 1993 | |||||

| Heads of the City Administration: | |||||||

| Nodar Khashba | 1993 | [54] | 26 November 1994 | Second time | |||

| 26 November 1994 | 1995 | [54] | Vladislav Ardzinba | ||||

| Garri Aiba | 1995 | 2000 | |||||

| Leonid Osia | 2 February 2000 | [40] | Acting Mayor | ||||

| Leonid Lolua | 2 February 2000 | [40] | 5 November 2004 | [42] | |||

| Adgur Kharazia | 5 November 2004 | [42] | 16 February 2005 | [43] | Acting Mayor, first time | ||

| Astamur Adleiba | 16 February 2005 | [43] | 2 May 2007 | [45] | Sergei Bagapsh | ||

| Anzor Kortua | May 2007 | 15 May 2007 | Acting Mayor | ||||

| Alias Labakhua | 15 May 2007 | 29 May 2011 | |||||

| 29 May 2011 | 1 June 2014 | Alexander Ankvab | |||||

| 1 June 2014 | 22 October 2014 | Valeri Bganba | |||||

| Adgur Kharazia | 22 October 2014 | Present | Raul Khajimba | Second time | |||

Transport

The city is served by several trolleybus and bus routes. Sukhumi is connected to other Abkhazian towns by bus routes.

There is a railway station in Sukhumi, that has a daily train to Moscow via Sochi.

Babushara Airport now handles only local flights due to the disputed status of Abkhazia.

Notable people

Notable people who are from or have resided in Sukhumi:

- Hadzhera Avidzba (1917 - 1997), Abkhazia's first professional pianist.

- Meri Avidzba (1917–1986), Abkhaz female pilot who fought during the Great Patriotic War of 1942–1945.

- Guram Gabiskiria (1947–1993), Mayor of Sukhumi and National Hero of Georgia.

- Demna Gvasalia (1981–present), Georgian fashion designer.

- Anatoli Kacharava (1910–1982), Georgian sea captain, serving in the Soviet Navy.

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Sukhumi is twinned with the following cities:

See also

- Sukhumi District

- List of twin towns and sister cities in Georgia

References

- Abkhazia is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Abkhazia and Georgia. The Republic of Abkhazia unilaterally declared independence on 23 July 1992, but Georgia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. Abkhazia has received formal recognition as an independent state from 7 out of 193 United Nations member states, 1 of which have subsequently withdrawn their recognition.

- https://ugsra.org/ofitsialnaya-statistika.php?ELEMENT_ID=386

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abkhazia". Encyclopedia Britannica. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopedia Britannica Inc. pp. 33. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Abkhaz Loans in Megrelian, p. 65

- Otar Kajaia, 2001–2004, Megrelian-Georgian Dictionary (entry aq'ujixa).

- Assays from the history of Georgia. Abkhazia from ancient times to the present day. Tbilisi, Georgia: Intelect. ISBN 978-9941-410-69-7.

- Colarusso, John. "More Pontic: Further Etymologies between Indo-European and Northwest Caucasian" (PDF). p. 54. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- Vita Sanctae Ninonis Archived 5 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. TITUS Old Georgian hagiographical and homiletic texts: Part No. 39

- Martyrium David et Constantini Archived 5 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. TITUS Old Georgian hagiographical and homiletic texts: Part No. 41

- Kartlis Cxovreba: Part No. 233. TITUS

- Goltz, Thomas (2009). "4. An Abkhazian Interlude". Georgia Diary (Expanded ed.). Armonk, New York / London, England: M.E. Sharpe. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7656-2416-1.

- Abkhazeti.info (in Russian)

- Room, A. (2005), Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features and Historic Sites. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, Jefferson, North Carolina, and London, ISBN 0-7864-2248-3, p. 361

- Абхазию и Южную Осетию на картах в РФ выкрасят в "негрузинские" цвета

- "Sokhumi". (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 November 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: Britannica.com

- "Sokhumi". (2006). In Encarta. Retrieved 6 November 2006: Encarta.msn.com Archived 30 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Esri ArcGis WebMap". Esri. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- "Google Maps changes Sukhumi to Sokhumi following Georgia's request". Agenda.ge. 10 February 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- "International Black Sea Club, members". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- Hyginus, Fabulae, 275

- Pomponius Mela, Chorographia, 1.111

- Ammianus Marcellinus, History, 22.8.24

- Solinus, Polyhistor, 15.17

- Arrian, Periplus of the Euxine Sea, 14

- Blair, William (1833). An inquiry into the state of slavery amongst the Romans. T. Clark. p. 25.

- Strabo, The Geography, BOOK XI, II, 16

- Hewitt, George (1998) The Abkhazians: a handbook St. Martin's Press, New York, p. 62, ISBN 0-312-21975-X

- Dioscurias. A Guide to the Ancient World, H.W. Wilson (1986). Retrieved 20 July 2006, from Xreferplus.com

- Vinogradov, Andrey (2014). "Some Notes On The Topography Of Eastern Pontos Euxeinos In Late Antiquity And Early Byzantium". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "ABKHAZIA – UNFALSIFIED HISTORY" Giorgi Sharvashidze.

- "Abkhazia – Unfalsified History" Zurab Papaskiri.

- "THE ABKHAZIANS AND ABKHAZIA" Mariam Lordkipanidze.

- "The Human Rights Watch report, March 1995 Vol. 7, No. 7". Hrw.org. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- 2003 Census statistics (in Russian)

- Population censuses in Abkhazia: 1886, 1926, 1939, 1959, 1970, 1979, 1989, 2003 (in Russian)

- Ю.Н. Воронов (Yury Voronov), "Келасурская стена" (Kelasuri wall). Советская археология 1973, 3. (in Russian)

- Voronya Peshchera. Show Caves of the World. Retrieved on 29 July 2008.

- "Sukhumi". climatebase.ru. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "Georgia, Sukhumi climate information". Travel-climate.com. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- "СООБЩЕНИЯ АПСНЫПРЕСС". Apsnypress. 2 February 2000. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- "Выпуск № 92". Apsnypress. 10 May 2001. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "MAYOR SUGGESTS ABKHAZ PRESIDENTIAL RIVALS SHOULD WITHDRAW". RFE/RL. 10 November 2004. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- "Указ Президента Абхазии №5 от 16.02.2005". Администрация Президента Республики Абхазия. 16 February 2005. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- "Президент Сергей Багапш подписал указы о назначении глав городских и районных администраций". Апсныпресс. 20 March 2007. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- "Abkhazia's anti-corruption drive". Institute for War & Peace Reporting. 20 March 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "Экс-мэр Сухуми вернул в бюджет двести тысяч рублей". REGNUM. 5 June 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- "Экс-мэр Сухума намерен покинуть Столичное городское Собрание". Администрация Президента Республики Абхазия. 23 July 2007. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- "Заместителем главы администрации столицы Абхазии назначен Вадим Черкезия". Caucasian Knot. 27 May 2007. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "АЛИАС ЛАБАХУА ИЗБРАН ДЕПУТАТОМ ГОРОДСКОГО СОБРАНИЯ СУХУМА". Апсныпресс. 3 September 2007. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- "СЕРГЕЙ БАГАПШ ПОДПИСАЛ УКАЗ О НАЗНАЧЕНИИ АЛИАСА ЛАБАХУА ГЛАВОЙ АДМИНИСТРАЦИИ ГОРОДА СУХУМ". Апсныпресс. 18 September 2007. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- "Адгур Харазия назначен исполняющим обязанности главы администрации г. Сухум". Apsnypress. 22 October 2014. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- "Итоги выборов". alhra.org. Избирательная комиссия по выборам в органы местного самоуправления г.Сухум. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- Khajimba, Raul. "УКАЗ О главе администрации города Сухум" (PDF). presidentofabkhazia.org. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- Lakoba, Stanislav. "Кто есть кто в Абхазии". Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "Сайт Администрации г.Подольска – Побратимы". Admpodolsk.ru. 15 June 2016. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- "Новости". Apsnypress.info. Archived from the original on 25 June 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- "12 мая между городами Абхазии и Италии были подписаны Протоколы о дружбе и сотрудничестве". Mfaapsny.org. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- "Il Sulcis rafforza il legame con i paesi dell'Est europeo, sottoscritto questa sera un protocollo d'amicizia con l'Abkhcazia". Laprovinciadelsulcisiglesiente.com. 9 April 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

Sources and external links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sukhumi. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sukhumi. |