Anklam

Anklam [German pronunciation: [ˈaŋklam] (![]()

Anklam | |

|---|---|

Market square | |

Coat of arms | |

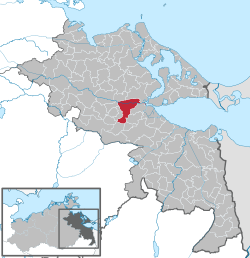

Location of Anklam within Vorpommern-Greifswald district  | |

Anklam  Anklam | |

| Coordinates: 53°51′N 13°41′E | |

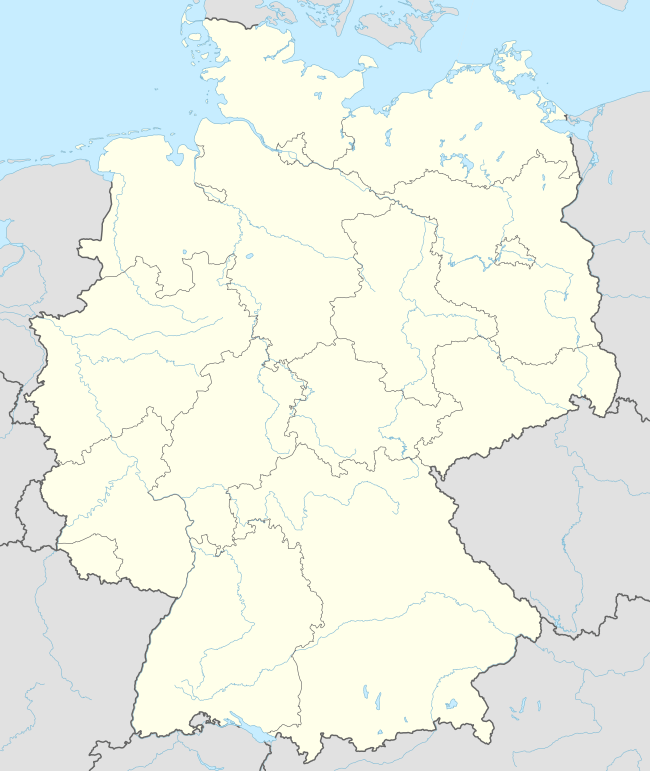

| Country | Germany |

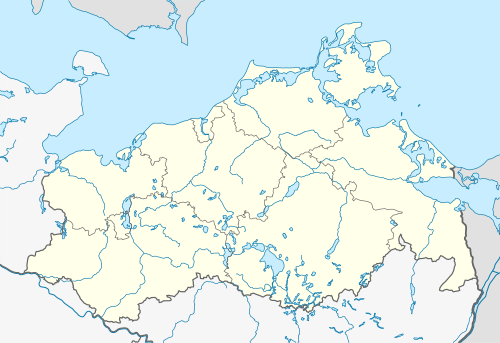

| State | Mecklenburg-Vorpommern |

| District | Vorpommern-Greifswald |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Michael Galander (Ind.) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 56.57 km2 (21.84 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 12,385 |

| • Density | 220/km2 (570/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 17389 |

| Dialling codes | 03971 |

| Vehicle registration | VG, ANK |

| Website | www.anklam.de |

History

In the early Middle Ages, there was an important Scandinavian and Wendish settlement in the area near the present town now known as Altes Lager Menzlin. Anklam proper began as an associated Wendish fortress.[3]

In the Middle Ages the town was a part of the Duchy of Pomerania. During the German expansion eastwards, the abandoned fortress was developed into a settlement named Tanglim[2] after its new founder. The site possesses importance as the head of navigation on the Peene.[2] It was elevated to town status in 1244 and became a member of the Hanseatic League the same year[3] or in 1483. The town remained small and non-influential, but achieved a measure of wealth and prosperity with its membership.

As a town of considerable military importance, it suffered greatly during the Thirty Years' War[2] when Swedish and Imperial troops battled over it across a twenty-year span. Amid this and subsequent wars, it also endured repeated outbreaks of fire and plague.[2] It was occupied by imperial forces from 1627 to 1630,[4] and thereafter by Swedish forces.[5] After the war, Anklam became part of Swedish Pomerania in 1648. In 1676, it was captured by Frederick William of Brandenburg.[3]

In 1713, Anklam was looted by soldiers of the Russian Empire.[3] That it was not burned to the ground, as ordered by Peter the Great, was in large part due to the resistance of Christian Thomesen Carl ("Carlson"), after whom a street is named in remembrance. The southern parts of the town were ceded to Prussia by the 1720 Treaty of Stockholm,[3] while a smaller section north of the Peene remained Swedish. It was damaged again during the Seven Years' War in the 1750s and '60s, with its fortifications being effectively dismantled in 1762.[2] Sweden yielded its remaining part of the town in 1815, when all of Western Pomerania became part of the Prussian province of Pomerania.

In the 19th century, Anklam was connected with Berlin and Stettin by rail and developed its manufacture of linen and woolen goods, leather, beer, and soap.[2] Its 1871 population was 10,739,[2] which had risen to 14,602 by the turn of the century.[3] By the time of the First World War, it possessed a military school and developed iron foundries and sugar factories.[3] In 1939 the Wehrmacht took over the military school and constructed a military prison on the grounds.

Anklam was nearly completely destroyed by several bombing raids of the U.S. Air Force in 1943 and 1944 and in the last days of World War II, when the advancing Soviets burned and leveled most of the town. After Prussia and its Pomeranian province were dissolved and most of Pomerania was allocated to Poland under the terms of the Potsdam Conference, Anklam became part of the East German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. That was soon to be dissolved, too, and Anklam was within the district of Neubrandenburg. The town was rebuilt in the rather uniform socialist style.

After the 1990 reunification of Germany, Anklam became part of the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, re-created at that time.

Population development

| Year | 1350 | 1600 | 1740 | 1765 | 1770 | 1790 | 1800 | 1875 | 1910 | 1939 | 1950 | 1981 | 1988 | 2003 | 2010 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Inhabitants | 3.000 | 6.000 | 2.961 | 3.036 | 3.278 | 3.224 | 4.470 | 11.781 | 15.279 | 19.682 | 20.160 | 20.496 | 19.685 | 15.826 | 13.433 | 12.635 | 12.521 |

Sights

Anklam was a prosperous medieval city but suffered severely during the Thirty Years' War, the Seven Years' War, and the Second World War, as well as from periodic fires. Nonetheless, Anklam has some significant buildings remaining. The 12th-century church of St Mary was rebuilt in the 15th century,[6] had a modern spire added in the 19th,[3] and was repaired in 1947.[6]

Museums

- Museum im Steintor (local history)

- Otto-Lilienthal-Museum

Transport

Anklam is connected with the Autobahn 20 coastal highway.

- Anklam railway station is served by national and local services to Angermünde, Berlin, Dresden, Eberswalde, Frankfurt, Munich, Prague and Stralsund.

People of Anklam

- early times

- Johann Franz Buddeus (1667–1729), philosopher, theologian, professor in Halle and Jena

- Paschen von Cossel (1714–1805), lawyer, imperial vicar, canon of the cathedral chapter Hamburger

- Friedrich Albrecht Karl Herrmann, Reichsgraf von Wylich und Lottum (1720–1797) Prussian officer

- Carl August Wilhelm Berends (1759–1826), physician, head of the Charité

- 19th C

- Ludwig von Henk (1820–1894), Vice Admiral of the Imperial Navy, member of Reichstag

- Otto Lilienthal (1848–1896), aviation pioneer

- Gustav Lilienthal (1849–1933) architect and social reformer

- Johanna Gadski (1872–1932), opera singer

- Julius Urgiß, (1873–1948), German-Jewish screenwriter and critic for Kinematograph

- Heinrich Sahm (1877–1939) a German lawyer, mayor of the Free City of Danzig

- Ulrich von Hassell, (1881–1944), German diplomat and anti-Nazi

- Kurt von Briesen (1886–1941), a German officer, most recently General of Infantry in WWII

- Alice Hechy (1893–1973), a German stage and film actress

- 20th C

- Günter Schabowski (1929–2015), politician (SED)

- Peter Hein (born 1943) a German rower, competed at the 1968 Summer Olympics

- Dixon (born Steffen Berkhahn in 1975) house and techno DJ, producer and label manager

- Matthias Schweighöfer, (born 1981), a German actor, voice actor, film director and producer.

- Sandro Stallbaum (born 1981) a retired German footballer, played for Werder Bremen

International relations

Anklam is twinned with:

See also

Notes

- "Statistisches Amt M-V – Bevölkerungsstand der Kreise, Ämter und Gemeinden 2018". Statistisches Amt Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (in German). July 2019.

- EB (1878).

- EB (1911).

- Langer, Herbert (2003), "Die Anfänge des Garnisionswesens in Pommern", in Asmus, Ivo; Droste, Heiko; Olesen, Jens E. (eds.), Gemeinsame Bekannte: Schweden und Deutschland in der Frühen Neuzeit (in German), Berlin: LIT Verlag, p. 403, ISBN 3-8258-7150-9

- Langer, Herbert (2003), "Die Anfänge des Garnisionswesens in Pommern", in Asmus, Ivo; Droste, Heiko; Olesen, Jens E. (eds.), Gemeinsame Bekannte: Schweden und Deutschland in der Frühen Neuzeit (in German), Berlin: LIT Verlag, p. 397, ISBN 3-8258-7150-9

- Brick Gothic Heritage Archived August 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 58

Further reading

- Gottfried Heinrich Gengler: Regesten und Urkunden zur Verfassungs- und Rechtsgeschichte der deutschen Städte im Mittelalter, Erlangen 1863, p. 47, see also pp. 962-966.

- Gustav Kratz: Die Städte der Provinz Pommern: Abriß ihrer Geschichte, zumeist nach Urkunden. Sändig Reprint Verlag, Vaduz 1996 (unchanged reprint of the edition of 1865), ISBN 3-253-02734-1, pp. 1-17.