Słupsk

Słupsk ([swupsk] (![]()

Słupsk | |

|---|---|

City Hall, New Gate, view from City Hall to the park and the Pomeranian Dukes Castle, Castle Complex (The Castle, Gate Mill, Granary Richter) | |

Flag | |

Słupsk  Słupsk | |

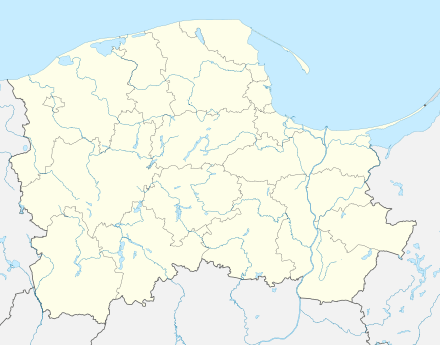

| Coordinates: 54°27′57″N 17°1′45″E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | |

| County | city county |

| Established | 10th century |

| Town rights | 1265 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Krystyna Danilecka-Wojewódzka (Spring) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 43.15 km2 (16.66 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 22 m (72 ft) |

| Population (December 2018) | |

| • Total | 91,007 |

| • Density | 2,216/km2 (5,740/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 76-200 to 76-210, 76-215, 76-216, 76-218, 76-280 |

| Area code(s) | +48 059 |

| Car plates | GS |

| Website | www.slupsk.pl |

Słupsk had its origins as a Pomeranian settlement in the early Middle Ages. In 1265 it was given town rights. By the 14th century, the town had become a centre of local administration and trade and a Hanseatic League associate. Between 1368 and 1478, it was the residence of the Dukes of Słupsk, until 1474 vassals of the Kingdom of Poland. In 1648, according to the peace treaty of Osnabrück, Stolp became part of Brandenburg-Prussia. In 1815 it was incorporated into the newly formed Prussian Province of Pomerania. After World War II, the city again became part of Poland, as it fell within the new borders determined by the Potsdam Conference.

Etymology

Slavic names in Pomeranian — Stolpsk,[3] Stôłpsk, Słëpsk, Słëpskò, Stôłp[4] — and Polish — Słupsk — may be etymologically related to the words słup ("pole") and stołp ("keep"). There are two hypotheses about the origin of those names: that it refers to a specific way of constructing buildings on boggy ground with additional pile support, which is still in use, or that it is connected with a tower or other defensive structure on the banks of the Słupia River.[3]

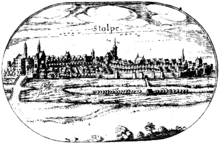

Later, during German rule, the town was named Stolp, to which the suffix in Pommern was attached in order to avoid confusion with other places similarly named. The Germanised name comes from one of five Slavic Pomeranian names of this settlement.[3] The city was occasionally called Stolpe, referring to the Słupia River, whose German name is Stolpe. Stolpe is also the Latin exonym for this place.[5]

History

Middle Ages

Słupsk developed from a few medieval settlements located on the banks of the Słupia River, at the unique ford along the trade route connecting the territories of modern Pomeranian and West Pomeranian Voivodeships. This factor led to the construction of a grod, a West Slavic or Lechitic fortified settlement, on an islet in the middle of the river. Surrounded by swamps and mires, the fortress had perfect defence conditions. Archaeological research has shown that the grod was situated on an artificial hill and had a natural moat formed by the branches of the Słupia, and was protected by a palisade. Records confirm that the area of Słupsk was part of the Polish realm during the reign of Mieszko I and in the 11th century.[6]

According to several sources, the first historic reference to Słupsk comes from the year 1015 when the king of Poland Boleslaus I the Brave took over the town, incorporating it into the Polish state. In the 12th century, the town became one of the most important castellanies in Pomerania alongside Gdańsk and Świecie.[7] However, several historians stated that the first mention was in two documents dating to 1227, signed by the Pomeranian dukes Wartislaw III and Barnim I and their mothers, confirming the establishment of an abbey in 1224 and donating estates, among them a village "in Stolp minore" or "in parvo Ztolp", respectively, to that abbey.[8] Another document dated to 1180, which mentions a "castellania Slupensis" and would thus be the oldest surviving record, has been identified as a late 13th-century or 14th-century duplicate.[8]

The Griffin dukes lost the area to the Samborides during the following years, and the next surviving documents mentioning the area concern donations made by Samboride Swietopelk II, dating to 1236 (two documents) and 1240.[9] In the earlier of the two 1236 documents, a Johann "castellanus de Slupcz" is mentioned as a witness,[10] Schmidt considers this to be the earliest mention of the gard, since a castellany required the existence of a gard.[11] The first surviving record explicitly mentioning the gard is from 1269: it notes a "Christianus, castellanus in castro Stolpis, et Hermannus, capellanus in civitate ante castrum predictum", thus confirming the existence of a fortress ("castrum") with a suburbium ("civitas").[11] Schmidt further says that the office of a capellanus required a church, which he identifies as Saint Peter's.[11] This church is mentioned by name for the first time in a 1281 document of Samboride Mestwin II, which also mentions Saint Nicolai church and a Saint Mary's chapel in the fortress.[12] The oldest mention of Saint Nicolai church dates to 1276.[12]

Modern Słupsk possibly received its city rights in 1265.[13] Historians argue that city rights were granted for the first time[12] in a document dated 9 September 1310 when Brandenburgian margraves Waldemar and Johann V granted those privileges under Lübeck law, which was confirmed and extended in a second document, dated 2 February 1313.[12] The margraves had acquired the area in 1307. Mestwin II accepted them as his superiors in 1269, confirmed in 1273,[14] but later on, in 1282, Mestwin II and Polish Duke Przemysł II signed the Treaty of Kępno, which transferred the suzerainty over Gdańsk Pomerania including Słupsk to Przemysł II. After Mestwin II's death the city was reintegrated with Poland and remained Polish until 1307, when the Margraviate of Brandenburg took over, while leaving local rule in the hands of the Swenzones dynasty, whose members were castellans in Słupsk.[15] In 1337, the governors of Słupsk (Stolp) had purchased the village of Stolpmünde (modern Ustka)[6] and then constructed a port there, enabling a maritime economy to develop. After the Treaty of Templin in 1317 the city passed to the Duchy of Pomerania-Wolgast.[16]

In 1368 Pomerania-Stolp (Duchy of Słupsk) was split off from Pomerania-Wolgast due to the Partitions of the Duchy of Pomerania. The grandson of Polish King Casimir III the Great and his would-be successor Casimir IV became duke of Słupsk as a Polish vassal in 1374, after he failed to take the Polish throne. The succeeding dukes were also vassals of the Kings of Poland: Wartislaw VII paid homage in 1390 (to King Władysław II Jagiełło),[17] Bogislaw VIII paid homage in 1410 (also to King Władysław II).[6] Słupsk remained within Polish sphere of political influence until 1474. It became part of the Duchy of Pomerania in 1478.

Modern ages

The Protestant Reformation reached the town in 1521, when Christian Ketelhut preached in the town. Ketelhut was forced to leave Stolp in 1522 due to an intervention by Bogislaw X, Duke of Pomerania. Peter Suawe, a Protestant from Stolp, however, continued his practices. In 1524, Johannes Amandus from Königsberg and others arrived and preached in a more radical way. As a consequence, Saint Mary's Church was profaned, the monastery's church was burned, and the clergy were treated poorly.[18] The inhabitants of the town began the process of conversion to Lutheranism. In 1560 Polish pastor Paweł Buntowski preached in the town, and in 1586 Polish religious literature spread locally.[6]

The House of Griffins, which ruled Pomerania for centuries, died out in 1637. The territory was subsequently partitioned between Brandenburg-Prussia and Sweden. After the Peace of Westphalia (1648) and the Treaty of Stettin (1653), Stolp came under Brandenburgian control. In 1660, Kashubian dialect was allowed to be taught but only in religious studies.[6] Polish language in general, however, was experiencing very unfavourable conditions due to depopulation of the area in numerous wars and implied Germanization.[19]

After the Thirty Years' War, Stolp lost much of its former importance—despite the fact that Szczecin was then a part of Sweden, the province's capital was situated not in the second-largest city of the region, but in the one closest to the former ducal residence—Stargard. However, the local economy stabilized. The constant dynamic development of the Kingdom of Prussia and good economic conditions saw the city develop. After the major state border changes (modern Vorpommern and Stettin joined the Prussian state after a conflict with Sweden) Stolp was only an administrative centre of the Kreis (district) within the Regierungsbezirk of Köslin (Koszalin). However, its geographical location led to rapid development, and in the 19th century, it was the second city of the province in terms of both population and industrialization.

In 1769, Frederick II of Prussia established a military school in the city, according to Stanisław Salmonowicz its purpose was the Germanization of local Polish nobility.[20]

During the Napoleonic Wars, the city was taken by 1,500 Polish soldiers under the leadership of general Michał Sokolnicki in 1807.[6] In 1815 Słupsk became one of the cities of the Province of Pomerania (1815–1945), in which it remained until 1945. In 1869 a railway from Danzig (Gdańsk) reached Stolp.

During the 19th century, the city's boundaries were significantly extended towards the west and south. The new railway station was built about 1,000 metres from the old city. In 1901, the construction of a new city hall was completed, followed by a local administration building in 1903. In 1910 a tram line was opened. The football club Viktoria Stolp was formed in 1901. In 1914, before the First World War, Stolp had approximately 34,340 inhabitants.

Interwar period

Stolp was not directly affected by the fighting in the First World War. The trams did not operate during the war, returning to the streets in 1919. Demographic growth remained high, although development slowed, because the city became peripheral, the Kreis (district) being situated on post-war Germany's border with the Polish Corridor. Polish claims to Stolp and its neighbouring area were refused during the Treaty of Versailles negotiations. The city, having become the regional center of the eastern part of Eastern Pomerania, thrived, becoming known as Little Paris. A cultural highlight was an annual art exhibition.[21]

From 1926 the city became an active point of Nazi supporters, and the influence of NSDAP grew rapidly.[6] The party with Hitler received 49.1% of the city's vote in the German federal election of March 1933[22], when however, the election campaign was marked by Nazi terror. During the Kristallnacht, the night of 9/10 November 1938, the local synagogue was burned down.[23]

Second World War

.jpg)

The beginning of the Second World War halted the development of the city. The Nazis created a labour camp near Słupsk, which became Außenarbeitslager Stolp, a subcamp of the Stutthof concentration camp. During the war, Germans brought forced labourers from occupied and conquered countries and committed numerous atrocities. People in the labour camp were maltreated physically and psychologically and forced to undertake exhausting work while being subject to starvation.[24]

Between July 1944 and February 1945, 800 prisoners were murdered by Germans in a branch of the Stutthof camp located in a railway yard in the city; today a monument honours the memory of those victims.[23] Other victims of German atrocities included 23 Polish children murdered between December 1944 and February 1945, and 24 Polish forced labourers (23 men and one woman) murdered by the Schutzstaffel (SS) on 7 March 1945, just before the Red Army took over the city without any serious resistance on 8 March 1945.[23] In fear of Soviet repression, up to 1,000 inhabitants committed suicide.[23][25] Thousands remained in the city; the others had fled and the German soldiers abandoned it. However, the Soviet soldiers were ordered to set fire to the historical central Old Town, which was almost completely destroyed.

Post-war period

After the war, according to the preliminary agreements of the conferences of Yalta and Potsdam, the German territories east of the Oder-Neisse line — most of Pomerania, Silesia and East Prussia — were transferred to Poland, pending a final peace conference with Germany[26], and from the middle of 1945 through to 1946 the remaining original population was expelled. The city was settled by Poles, most of whom were expelled from the former Polish eastern territories annexed by the Soviet Union (around 80% at the end of 1945) and the rest were mainly repatriates from the Soviet Union and Poles returning from Germany.[27] Also Ukrainians and Lemkos settled into the town during Operation Vistula.

The town's name was changed into "Słupsk" (the historic Polish version of its name) by the Commission for the Determination of Place Names on 23 April 1945. It was initially part of Okręg III, comprising the whole territory of the former Province of Pomerania east of the Oder River. Słupsk later became part of Szczecin Voivodeship and then Koszalin Voivodeship, and in 1975 became the capital of the new province of Słupsk Voivodeship.

Life in the devastated city was organized anew. In 1945, the first post-war craft workshops and public schools were opened, trams and a regional railway started to operate, and the amateur Polish Theater was established.[27] In September 1946, the first Warsaw Uprising Monument in Poland was unveiled.[27] From April 1947, the local Polish newspaper Kurier Słupski was published.[27] The city became a cultural centre. In the 1950s, the Puppet Theater Tęcza, the Teachers' College and the Baltic Dramatic Theater were established.[27] The puppet theatre Tęcza used to collaborate with the similar institution called Arcadia in Oradea, Romania, but the partnership ceased after 1989. The Millennium Cinema was one of the first in Poland to have a cinerama. The first Polish pizzeria was established in Słupsk in 1975.[28]

During the 1970 protests there were minor strikes and demonstrations. None were killed during the militia's interventions.

After 1989

Major street name changes were made in Słupsk after the Revolutions of 1989. Also, a process of major renovations and refurbishments began, beginning in the principal neighbourhoods. According to the administrative reform of Poland in 1999, Słupsk Voivodeship was dissolved and divided between two larger regions: Pomeranian Voivodeship and West Pomeranian Voivodeship. Słupsk itself became part of the former. The reform was criticized by locals, who wanted to create a separate Middle Pomeranian Voivodeship.[29] In 1998 a major riot took place after a basketball game.

In 2014, Słupsk elected Poland's first openly gay mayor, Robert Biedroń.[30]

Geography

Boundaries

Administratively, the city of Słupsk has the status of both an urban gmina and a city county (powiat). The city boundaries are generally artificial, with only short natural boundaries around the villages of Kobylnica and Włynkówko on the Słupia River. The boundaries have remained unchanged since 1949, when Ryczewo became a part of the city.

Słupsk shares about three-quarters of its boundaries with the rural district called Gmina Słupsk, of which Słupsk is the administrative seat (although it is not part of the district). The city's other neighbouring district is Gmina Kobylnica, to the south-west. The Słupsk Special Economic Zone is not entirely contained within the city limits: a portion of it lies within Gmina Słupsk, while some smaller areas are at quite a distance from Słupsk (Debrzno), or even in another voivodeship (Koszalin, Szczecinek, Wałcz).

The city has a fairly irregular shape, with its central point at Plac Zwycięstwa ("Victory Square") at 54°27′51″N 17°01′42″E.

Topography

Słupsk lies in an pradolina of the Słupia River. The city centre is situated significantly lower than its western and easternmost portions. Divided into two almost equal parts by the river, Słupsk is hilly when compared to other cities in the region. About 5 square kilometres (1.9 sq mi) of the city's area is covered by forests, while 17 square kilometres (6.6 sq mi) is used for agricultural purposes.

Słupsk is rich in natural water bodies. There are more than twenty ponds, mostly former meanders of the Słupia, within the city limits. There are also several streams, irrigation canals (generally unused and abandoned) and a leat. Except in the city centre, all these watercourses are unregulated.

There is generally little human influence on landform features visible within the city limits. However, in the northwestern part of the city there is a huge hollow, a remnant of a former sand mine. Although there were once plans to build a waterpark in this area,[31] they were later abandoned and the site remains unused.

Climate

Słupsk has a temperate marine climate, like the rest of the Polish coastal regions.[32] The city lies in a zone where the continental climate influences are very weak compared with other regions of Poland.[33] The warmest month is July, with an average temperature range of 11 to 21 °C (52 to 70 °F). The coolest month is February, averaging −5 to 0 °C (23 to 32 °F). The wettest month is August with average precipitation of 90 millimetres (3.5 in), while the driest is March, averaging only 20 millimetres (0.79 in). Snowfalls are always possible between December and April.

| Climate data for Słupsk | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0 (32) |

0 (32) |

3 (37) |

10 (50) |

16 (61) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

18 (64) |

12 (54) |

6 (43) |

2 (36) |

11 (52) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4 (25) |

−5 (23) |

−2 (28) |

1 (34) |

5 (41) |

9 (48) |

11 (52) |

11 (52) |

8 (46) |

5 (41) |

1 (34) |

−1 (30) |

3 (37) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 40 (1.6) |

30 (1.2) |

20 (0.8) |

30 (1.2) |

50 (2.0) |

60 (2.4) |

80 (3.1) |

90 (3.5) |

60 (2.4) |

50 (2.0) |

40 (1.6) |

50 (2.0) |

660 (26.0) |

| Source: Meteo.Pl[34] | |||||||||||||

Neighbourhoods

The neighbourhoods (osiedla, singular osiedle) of Słupsk do not have any administrative powers. Their names are used for traffic signposting purposes and are shown on maps. The neighbourhoods are as follows:

- Nadrzecze ("Riverside") — situated in the southern part of the city, this district is a major industrial area. It is bounded by the railroad to the west, Deotymy and Jana Pawła II streets to the north, the Słupia river to the east and the city boundary to the south.

- Osiedle Akademickie ("Academic Neighbourhood") — a neighbourhood of detached and semi-detached houses around the Pomeranian Academy and its halls of residence.

- Osiedle Bałtyckie ("Baltic Neighbourhood") — the northernmost neighbourhood of Słupsk, a large part of which belongs to the Słupsk Special Economic Zone.

- Osiedle Niepodległości ("Independence Neighbourhood") (before 1989 called Osiedle Budowniczych Polski Ludowej or "Neighbourhood of the Builders of People's Poland", and still popularly referred to as BPL) and Osiedle Piastów ("Piast Neighbourhood") — these neighbourhoods make up the largest residential area of the city, inhabited by about 40,000 people.

- Osiedle Słowińskie ("Slovincian Neighbourhood") — the easternmost part of Słupsk, similar in character to Osiedle Akademickie. It adjoins the Northern Wood (Lasek Północny) and is close to the city's boundary with Redzikowo, the planned site of the US national missile defense interceptors.

- Ryczewo — brought within the city limits in 1949, this is the youngest neighbourhood of Słupsk. Before the Second World War it was a villa district. It has retained much of its village character.

- Stare Miasto ("Old Town"; also known as Śródmieście or Centrum — "the City Centre") — the central district of Słupsk containing the historic centre of the city including the city hall and the Pomeranian Dukes' Castle.

- Westerplatte (known also as Osiedle Hubalczyków-Westerplatte) — a large and fast-developing area in the south-east of Słupsk, including the city's highest point. Currently both detached houses and blocks of flats are being built here.

- Zatorze (usually further subdivided into Osiedle Jana III Sobieskiego and Osiedle Stefana Batorego) — the second largest residential area, with 10,000 inhabitants. According to police statistics, it is the most dangerous area of the city.

Parks

Słupsk has many green areas within its boundaries. The most important are the Park of Culture and Leisure (Park Kultury i Wypoczynku), the Northern Wood (Lasek Północny) and the Southern Wood (Lasek Południowy). There are also many small parks, squares and boulevards.

Transport

Railways

Słupsk is a railway junction, with four lines running north, west, east and south from the city.[35] Currently, one station, opened January 10, 1991 serves the whole city. This is a class B station according to PKP (Polish Railways) criteria.[36] The city has rail connections with most major cities in Poland: Białystok, Gdańsk, Gdynia, Katowice, Kraków, Lublin, Łódź, Olsztyn, Poznań, Szczecin, Warsaw and Wrocław, and also serves as a junction for local trains from Kołobrzeg, Koszalin, Lębork, Miastko, Szczecinek and Ustka. Słupsk is the westernmost terminus of the Fast Urban Railway serving the Gdańsk conurbation.[37]

The first railway reached Słupsk (then Stolp) from the east in 1869. The first rail station was built north of its current location. The line was later extended to Köslin (Koszalin), and further lines were built connecting the city with Neustettin (Szczecinek), Stolpmünde (Ustka), Zezenow (Cecenowo) (narrow gauge) and Budow (Budowo) (narrow gauge). The narrow-gauge tracks were rebuilt as standard gauge by 1933, but were demolished during the Second World War. After the war, the first train connection to be restored was that with Lębork, reopened May 27, 1945. Between 1988 and 1989 almost all of the lines traversing the city were electrified. From 1985 to 1999 Słupsk had a trolleybus system.

Roads

Słupsk used to be traversed east-west by European route E28, which is known as National route 6 in Poland until a bypass running to the south of the town to carry the 6/E28 traffic was built. The bypass is a part of Expressway S6 which, when completed some time after 2015, will give Słupsk a fast road connection to Szczecin and Gdańsk. The city can also be accessed by the National route 21 from Miastko, Voivodeship route 210 from Ustka to Unichowo and Voivodeship route 213 from Puck. Local roads of lesser importance connect Słupsk with surrounding villages and towns.

The city's network of streets is well developed, but many of them require general refurbishment. The city is currently investing significant sums of money in road development.

Air

Słupsk-Redzikowo Airport is now defunct, however, it once worked as a regular passenger airport of local significance. Several plans to eventually reopen it failed because of lack of funds. The facility was earmarked for use within the US missile defense complex as a missile launch site. Policy changes by the US government regarding the missile shield have made this development unlikely however.

Monuments

- Słupsk Town Hall (Victory Square 3)

- A new Town Hall (Victory Square 1)

- County Office (Victory Szeregów 14)

- Pomeranian Dukes Castle (Dominikańska Street 5 - 9)

- Municipal Public Library (Grodzka Street 3)

- The Castle Mill (Dominikańska Street 5 - 9) - the oldest industrial structure in Poland

- Post-Dominican church of St. Jack (Dominikańska Street 5-9)

- Church of Virgin Mary (Nowobramska Street)

- The Church of the Holiest Heart of Jesus (Armii Krajowej Street 22)

- The Church of the Holy Cross (Słowacki Street 42)

- Monastery Church under the invocation of St. Otto (Henryk Pobożny Street 7)

- New Gate (Vistory Square 12)

- The Mill Gate (Dominikańska Street 5-9)

- Richter's granary (Dominikańska Street 5-9)

- On the hill next to dr Maxa Josepha Street there is a Former funeral home of Jewish Commune (synagogue) (dr Max Joseph Street)

- Old Brewery in Słupsk (Kiliński Street 26-28)

- Defensive walls

- 'Słowiniec' Department Store, with the oldest wooden lift in Europe (Victory Square 11)

- Witches’ Tower (Nullo Street 13)

- Main Post Office (Łukasiewicz Street 3)

Culture

Słupsk is the regular venue for a number of festivals, most notably:

- the "Solidarity" International Contract Bridge Festival (Międzynarodowy Festiwal Brydża Sportowego "Solidarność")

- the Komeda Jazz Festival

- the "Performance" International Art Festival (Międzynarodowy Festiwal Sztuki "Performance")

- an International Piano Festival

For a long time here lived Anna Łajming (1904–2003), Kashubian and Polish author.

The museum in Słupsk holds the world's biggest collection of Witkacy's works.

Theatres

Słupsk currently has three theatres:

- the Tęcza ("Rainbow") Theatre

- the Rondo ("Roundabout") Theatre

- the New Theatre, reopened after a 13-year absence

In the 1970s the Tęcza Theatre collaborated with the Arcadia Theatre from Oradea, Romania. This partnership ended after 1989 for political reasons.

Cinemas

At one time Słupsk had five functioning cinemas, but only one, which belongs to the cinema chain Multikino remains open today, which is located in the Jantar Shopping Centre. There is also a small specialist cinema called "Rejs" on 3 Maja street. There was a cinema called 'Milenium', which has now been replaced by the Biedronka chain of supermarkets.

Economy

Słupsk has a developing economy based on a number of large factories. The footwear industry has been particularly successful in the region, expanding its exports to many countries.

The Scania commercial vehicles plant also plays a very significant role in Słupsk's economy, generating the highest revenue out of all companies currently based in Słupsk. Most of the buses currently manufactured there are exported to Western Europe.

Demographics

Before the end of World War II, the vast majority of the town's population was composed of Protestants.

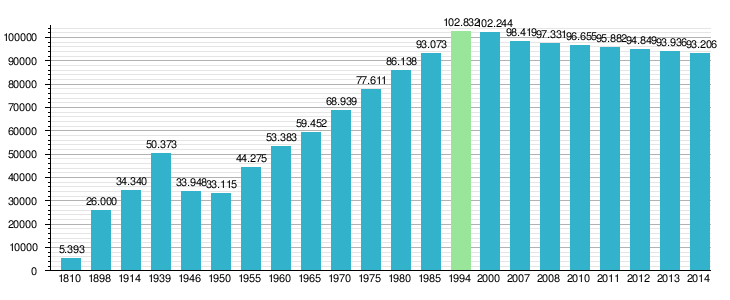

- Number of inhabitants in years

- 1740: 2,599[38]

- 1782: 3,744, incl. 40 Jews[38]

- 1794: 4,335, incl. 39 Jews[38]

- 1812: 5,083, incl. 55 Catholics and 63 Jews[38]

- 1816: 5,236, incl. 58 Catholics and 135 Jews[38]

- 1831: 6,581, incl. 36 Catholics and 239 Jews[38]

- 1843: 8,540, incl. 58 Catholics and 391 Jews[38]

- 1852: 10,714, incl. 50 Catholics and 599 Jews[38]

- 1861: 12,691, incl. 45 Catholics, 757 Jews, one Mennonite and 46 German Catholics.[38]

- 1905: 31,154 (incl. the military), among these 951 Catholics and 548 Jews[39]

- 1925: 41,605, incl. 1,200 Catholics and 469 Jews[40]

- 1933: 45,307[41]

- 1939: 48,060[41]

In 1994 the number of inhabitants reached the highest level.

Sports clubs

The city's most notable sports club is basketball team Czarni Słupsk, which competes in the I Liga (Polish second tier), but until 2018 played in the Polish Basketball League (top division),[42] where they finished 3rd four times. They are based in Hala Gryfia.

Other clubs include:

- Akademia Tenisa Oxford: tennis

- Gryf Słupsk: football

- Słupia Słupsk: handball

- Słupski Klub Sportowy Piast-B: badminton

- SKB Czarni Słupsk: boxing

- TPS Czarni Słupsk: women's volleyball

- Towarzystwo Pływackie Skalar Słupsk: swimming

- AML Słupsk: athletics

- LKS Fenix: athletics

- STS Gryf 3 Słupsk : judo

US missile defense complex

The European Interceptor Site (EIS) of the US was planned in nearby Redzikowo, forming a Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system in conjunction with a US narrow-beam midcourse tracking and discrimination radar system in the Czech Republic. It was supposed to consist of up to 10 silo-based interceptors, a two-stage version of the existing three-stage Ground Based Interceptor (GBI), with Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle (EKV).

The missile shield has received much local opposition in the area, including several protests. This included a protest in March 2008, when an estimated 300 protesters marched on the proposed site of the missile base.[43] The planned installation was later scrapped by President Obama on 17 September 2009.[44]

On February 12, 2016, the US Army has awarded AMEC Foster Wheeler a $182.7 million contract with an option to support the Aegis Ashore missile defense system in Poland. The contract comes as part of Phase III of the European Phased Adaptive Approach program, which aims to boost land-based missile defense systems for NATO allies against ballistic missile threats. Project is located in Redzikowo, the site that was formerly scrapped.[45]

Notable citizens

.jpg)

Early times

- Erdmuthe of Brandenburg (1561–1623), Princess of Brandenburg, died in Stolp

- Michael Brüggemann (1583–1654), German Lutheran pastor, preacher and translator

- Matthias Palbitzki (1623–1677), Swedish diplomat and art-connoisseur

- Andrzej Stech (1635–1697), Polish Baroque painter

- Eduard von Bonin (1793–1865), Prussian General, minister of war

19th Century

- Heinrich von Stephan (1831–1897), German official, founder of the Universal Postal Union[46]

- Berthold Suhle (1837–1904), German chess master

- Wilhelm Dames (1843–1898), German paleontologist

- Otto Liman von Sanders (1855–1929), German general

- Georg von der Marwitz (1856–1929), German general

- Hedwig Lachmann (1865–1918), German author, translator and poet

- Hans Schrader (1869–1948), German classical archaeologist and art historian

- Erwin Bumke (1874–1945), German jurist

- Oswald Bumke (1877–1950), German psychiatrist, neurologist

- Otto Freundlich (1878–1934), German painter and sculptor, an abstract artist

- Walter Lichel (1885–1969) German general

- George Grosz (1893–1959), German artist, satirical caricaturist

20th Century

- Paul Mattick (1904–1981), American Marxist political writer

- Flockina von Platen (1905–1984), German actress

- Mieczysław Kościelniak (1912–1993), Polish painter, graphic designer and draftsman

- Bronisław Kostkowski (1915–1942), Polish Roman Catholic seminarian

- Odo Marquard (1928–2015), German philosopher, a member of the Ritter School

- Christian Meier (born 1929), German historian

- Edgar Wisniewski (1930–2007), German architect

- Bazon Brock (born 1936), German art theorist, critic and artist; member of Fluxus

- Dieter Stöckmann (born 1941), German general

- Jörg Schmeisser (1942–2012), printmaker

- Simone Barck (1944–2007), German contemporary historian and literary scholar

- Ulrich Beck (1944–2015), German sociologist

- Grażyna Auguścik (born 1955), Polish jazz vocalist, composer, and arranger

- Jolanta Szczypińska (1957–2018), Polish politician

- Edward Müller (born 1958), Polish politician and trade union activist

- Przemysław Gosiewski (1964–2010), Polish politician, deputy chair of Law and Justice party

- Tomasz Malinowski (born 1965), Polish-American diplomat and politician

- Sarsa Markiewicz (born 1989), Polish singer, songwriter and record producer.

- Sport

- Heinz Radzikowski (born 1925) a German field hockey player, competed in the 1956 Summer Olympics

- Harry Klugmann (born 1940) a German equestrian and Olympic medallist at the 1972 Summer Olympics

- Halina Aszkiełowicz-Wojno (1947–2018) Polish volleyball player, bronze medalist 1968 Summer Olympics

- Darius Grala (born 1964) an endurance sports car racing driver in the USA

- Robert Kraskowski (born 1967) a Polish sport shooter, competed at the 1992 and 1996 Summer Olympics

- Mirosława Sagun-Lewandowska (born 1970) air gun champion, participant in three Olympic Games

- Tomasz Iwan, (born 1971) Polish football (soccer) player

- Paweł Kryszałowicz (born 1974) a Polish footballer, represented Poland in 33 matches scoring 10 goals

- Milena Rosner (born 1980), volleyball player, participant in the 2008 Summer Olympics

- Kamila Augustyn (born 1982) a Polish badminton player, competed at the 2008 and 2012 Summer Olympics

- Miłosz Bernatajtys (born 1982) a Polish rower, silver medallist at the 2008 Summer Olympics

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Słupsk is twinned with:

|

See also

- Słupsk (PKP station)

- Town Hall of Słupsk

References

- Literature

- (in German) Helge Bei der Wieden and Roderich Schmidt, eds.: Handbuch der historischen Stätten Deutschlands: Mecklenburg/Pommern, Kröner, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 978-3-520-31501-4, pp. 287–290.

- (in German) Haken, Christian Wilhelm: Drei Beiträge zur Erläuterung der Stadtgeschichte von Stolp (Three Contributions to Explaining the History of the Town of Stolp) (1775). Newly edited by F. W. Feige, Stolp, 1866 (online)

- (in German) Kratz, Gustav: Die Städte der Provinz Pommern, Abriss ihrer Geschichte, zumeist nach Urkunden (The Towns of the Province of Pomerania - Sketch of their History, Mainly According to Historical Records). Berlin, 1865 (reprinted in 2010 by Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 1-161-12969-3), pp. 413–439 ( online)

- (in German) Pagel, Karl-Heinz: Stolp in Pommern - eine ostdeutsche Stadt. Lübeck, 1977 (with extensive bibliography, online)

- (in German) Reinhold, Werner: Chronik der Stadt Stolp (Chronicle of the Town of Stolp). Stolp, 1861 (online)

- Notes

- Collaborative work (2007). Powierzchnia i ludność w przekroju terytorialnym w 2007 (in Polish). Central Statistical Office.

- Collaborative work (1999). Gminy w Polsce (in Polish). Central Statistical Office.

- "Słupsk.pl: Informacje ogólne" (in Polish). Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- "Nasze Kaszuby: Zestawienie kaszubskich i polskich nazw miejscowości na Kaszubach, z wariantami, z wyszczególnieniem powiatów" (in Polish and Kashubian). Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- "Lexicon Universale" (in Latin). Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- Archived 2010-08-26 at the Wayback Machine Historia Słupska do roku 1945. Official webpage of the city. (in Polish)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved 2009-08-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Historia. Official webpage of the city

- Schmidt, Roderich (2009). Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse. Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern (in German). 41 (2 ed.). Köln-Weimar: Böhlau. p. 140. ISBN 3-412-20436-6.

- Schmidt, Roderich (2009). Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse. Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern (in German). 41 (2 ed.). Köln-Weimar: Böhlau. p. 142. ISBN 3-412-20436-6.

- Schmidt, Roderich (2009). Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse. Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern (in German). 41 (2 ed.). Köln-Weimar: Böhlau. pp. 142, 147. ISBN 3-412-20436-6.

- Schmidt, Roderich (2009). Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse. Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern (in German). 41 (2 ed.). Köln-Weimar: Böhlau. p. 147. ISBN 3-412-20436-6.

- Schmidt, Roderich (2009). Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse. Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern (in German). 41 (2 ed.). Köln-Weimar: Böhlau. p. 148. ISBN 3-412-20436-6.

- "Słupsk.pl: Historia Słupska do roku 1945" (in Polish). Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- Schmidt, Roderich (2009). Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse. Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern (in German). 41 (2 ed.). Köln-Weimar: Böhlau. pp. 143–144. ISBN 3-412-20436-6.

- Schmidt, Roderich (2009). Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse. Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern (in German). 41 (2 ed.). Köln-Weimar: Böhlau. pp. 144–145. ISBN 3-412-20436-6.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Barthold, Geschichte von Rügen und Pommern, 1842, p. 156

- Juliusz Bardach, Historia państwa i prawa Polski, Volume 1, Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe, 1964, p. 589

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.211, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- Język polski, Tomy 19-20 Towarzystwo Miłośników Języka Polskiego, page 194, W Drukarni Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, 1999

- Polacy i Niemcy wobec siebie Stanisław Salmonowicz, Ośrodek Badań Naukowych im. W. Kętrzyńskiego 1993, page 43

- Edda Gutsche (2018). Mit Ausblick auf Park und See. Zu Gast in Schlössern und Herrenhäusern in Pommern und der Kaschubei (in German). Elmenhorst/Vorpommern: edition Pommern. p. 63. ISBN 978-3-939680-41-3.

- "Deutsche Verwaltungsgeschichtevon der Reichseinigung 1871 bis zur Wiedervereinigung 1990 von Dr. Michael Rademacher M.A." Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2011-08-08.

- Słupsk po wybuchu II wojny światowej

- Archived 2010-08-26 at the Wayback Machine Słupsk po wybuchu II wojny światowej. Official city webpage

- Lakotta, Beate (2005-03-05). "Tief vergraben, nicht dran rühren". SPON (in German). Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- Geoffrey K. Roberts, Patricia Hogwood (2013). The Politics Today Companion to West European Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9781847790323.; Piotr Stefan Wandycz (1980). The United States and Poland. Harvard University Press. p. 303. ISBN 9780674926851.; Phillip A. Bühler (1990). The Oder-Neisse Line: a reappraisal under international law. East European Monographs. p. 33. ISBN 9780880331746.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-06. Retrieved 2019-06-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) Historia Słupska po roku 1945. Official webpage of the city (in Polish)

- "Pizza Słupsk Info". Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- "Legislative proposal of July 24, 1998, regarding the introduction of the three-level administrative division of Poland" (in Polish). Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- Gera, Vanessa (1 December 2014). "Poland elects first openly gay mayor in elections". The Big Story. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 3 December 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "Gp24.pl: Coraz bliżej aquaparku" (in Polish). Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- Kaczmarek, T., Kaczmarek, U., Sołowiej D., Wrzesiński, D. (2002). Ilustrowana Geografia Polski (in Polish). Świat Książki.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Collaborative work (2000). Altas geograficzny dla szkół średnich (in Polish). PPWK.

- "Weatherbase".

- "Kolej.One.Pl: Słupsk" (in Polish). Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- "List of stations maintained by Dworce Kolejowe" (PDF) (in Polish). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 9, 2006. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- "SKM network map" (in Polish). Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- Kratz (1865), p. 430

- Meyers Konversations-Lexikon. 6th edition, vol. 19, Leipzig and Vienna 1909, p. 60 (in German)

- Gunthard Stübs und Pommersche Forschungsgemeinschaft: Die Stadt Stolp im ehemaligen Stadt Stolp in Pommern Archived 2013-01-09 at the Wayback Machine, 2011. (in German)

- verwaltungsgeschichte.de Archived 2011-07-23 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- "Czarni Słupsk wycofali się z Energa Basket Ligi, więc Legia się utrzyma" (in Polish). Sport.pl. 31 January 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Protesters March on Proposed US Missile Base

- President Obama announces scrapping the planned missile defense system in Poland and the Czech Republic New York Times Retrieved on 09-17-09

- Defense Industry Daily Retrieved on 02-18-16

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 879.

- Информация о городах-побратимах (in Russian). www.arhcity.ru. 2007-10-26. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- Carlisle City Council. "Town twinning". carlisle.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- "Town Twinning at Carlisle City Council". carlisletwins.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Słupsk. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ulice Słupska. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 955.

- Municipal website

- Museum of Central Pomerania

- History of Slupsk

- Solidarity International Bridge Festival

- March 29th, 2008: Demonstration Against U.S. Missile Defence Shield