Chișinău

Chișinău (/ˌkɪʃɪˈnaʊ/ KISH-ih-NOW, also US: /ˌkiːʃiːˈnaʊ/ KEE-shee-NOW, Romanian: [kiʃiˈnəw] (![]()

Chișinău Кишинёв | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): Orașul din piatră albă ("The city of white stone") | |

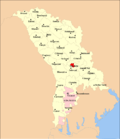

Chișinău Location of Chisinau in Moldova  Chișinău Chișinău (Europe) | |

| Coordinates: 47°01′22.3932″N 28°50′07.2060″E | |

| Country | |

| First written mention | 1436[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ion Ceban |

| Area | |

| • City | 123 km2 (47 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 563.3 km2 (217.5 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 85 m (279 ft) |

| Population (2014 census)[3] | |

| • City | 532,513 |

| • Estimate (January 1, 2020) | 700,000[4] |

| • Density | 4,329/km2 (11,210/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 820,500 [5] |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+03:00 (EEST) |

| Postal code | MD-20xx |

| Area code(s) | +373-22 |

| ISO 3166 code | MD-CU |

| GRP(nominal)[6] | 2016 |

| – Total | $4 billion |

| – Per capita | $5,000 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.777[7] high · 1st |

| Website | www.chisinau.md |

| a As the population of the Municipality of Chișinău (which comprises the city of Chișinău and 34 other suburban localities)[8] | |

Etymology

The origin of the city's name is unclear. A theory suggests that the name may come from the archaic Romanian word chișla (meaning "spring", "source of water") and nouă ("new"), because it was built around a small spring, at the corner of Pușkin and Albișoara streets.[10]

The other version, formulated by Ștefan Ciobanu, Romanian historian and academician, holds that the name was formed the same way as the name of Chișineu (alternative spelling: Chișinău) in Western Romania, near the border with Hungary. Its Hungarian name is Kisjenő, from which the Romanian name originates.[11] Kisjenő comes from kis "small" and the Jenő, one of the seven Hungarian tribes that entered the Carpathian Basin in 896. At least 24 other settlements are named after the Jenő tribe.[12][13]

Chișinău is known in Russian as Кишинёв (Kishinjóv), while Moldova's Russian-language media call it Кишинэу, [kʲɪʂɨˈnɛʊ] (Kishineu). It is written Kişinöv in the Latin Gagauz alphabet. It was also written as Chișineu in pre-20th-century Romanian[14] and as Кишинэу in the Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet. Historically, the English language name for the city, Kishinev, was based on the modified Russian one because it entered the English language via Russian at the time Chișinău was part of the Russian Empire (e.g. Kishinev pogrom). Therefore, it remains a common English name in some historical contexts. Otherwise, the Romanian-based Chișinău has been steadily gaining wider currency, especially in written language. The city is also historically referred to as German: Kischinau, Polish: Kiszyniów, Ukrainian: Кишинів, romanized: Kyshyniv, or Yiddish: קעשענעװ, romanized: Keshenev.

History

Moldavian period

Founded in 1436 as a monastery village, the city was part of the Principality of Moldavia (which, starting with the 16th century became a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire, but still retaining its autonomy). At the beginning of the 19th century Chișinău was a small town of 7,000 inhabitants.

In 1812, in the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812), the eastern half of Moldavia was ceded to the Russian Empire. The newly acquired territories became known as Bessarabia.

Russian Imperial period

Under Russian government, Chișinău became the capital of the newly annexed oblast (later guberniya) of Bessarabia. By 1834, an imperial townscape with broad and long roads had emerged as a result of a generous development plan, which divided Chișinău roughly into two areas: the old part of the town, with its irregular building structures, and a newer city centre and station. Between 26 May 1830 and 13 October 1836 the architect Avraam Melnikov established the Catedrala Nașterea Domnului with a magnificent bell tower. In 1840 the building of the Triumphal arch, planned by the architect Luca Zaushkevich, was completed. Following this the construction of numerous buildings and landmarks began.

On 28 August 1871, Chișinău was linked by rail with Tiraspol, and in 1873 with Cornești. Chișinău-Ungheni-Iași railway was opened on 1 June 1875 in preparation for the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). The town played an important part in the war between Russia and Ottoman Empire, as the main staging area of the Russian invasion. During the Belle Époque, the mayor of the city was Carol Schmidt, considered one of Chisinau's best mayors. Its population had grown to 92,000 by 1862, and to 125,787 by 1900.[15]

Pogroms and pre-revolution

In the late 19th century, especially due to growing anti-Semitic sentiment in the Russian Empire and better economic conditions in Moldova, many Jews chose to settle in Chișinău. By the year 1897, 46% of the population of Chișinău was Jewish, over 50,000 people.[16]

As part of the pogrom wave organized in the Russian Empire, a large anti-Semitic riot was organized in the town on 19–20 April 1903, which would later be known as the Kishinev pogrom. The rioting continued for three days, resulting in 47 Jews dead, 92 severely wounded, and 500 suffering minor injuries. In addition, several hundred houses and many businesses were plundered and destroyed.[17] Some sources say 49 people were killed.[18] The pogroms are largely believed to have been incited by anti-Jewish propaganda in the only official newspaper of the time, Bessarabetz (Бессарабецъ). Mayor Schmidt disapproved of the incident and resigned later in 1903. The reactions to this incident included a petition to Tsar Nicholas II of Russia on behalf of the American people by US President Theodore Roosevelt in July 1903.[19]

On 22 August 1905 another violent event occurred: The police opened fire on an estimated 3,000 demonstrating agricultural workers. Only a few months later, 19–20 October 1905, a further protest occurred, helping to force the hand of Nicholas II in bringing about the October Manifesto. However, these demonstrations suddenly turned into another anti-Jewish pogrom, resulting in 19 deaths.[19]

Romanian period

Following the Russian October Revolution, Bessarabia declared independence from the crumbling empire, as the Moldavian Democratic Republic, before joining the Kingdom of Romania. As of 1919, Chișinău, with an estimated population of 133,000,[20] became the second largest city in Romania.

Between 1918 and 1940, the center of the city undertook large renovation work. Romania granted important subsidies to its province and initiated large scale investment programs in the infrastructure of the main cities in Bessarabia, expanded the railroad infrastructure and started an extensive program to eradicate illiteracy.

In 1927, the Stephen the Great Monument, by the sculptor Alexandru Plămădeală, was erected. In 1933, the first higher education institution in Bessarabia was established, by transferring the Agricultural Sciences Section of the University of Iași to Chișinău, as the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences.

World War II

._(8257398062).jpg)

._(17821899839).jpg)

.jpg)

On 28 June 1940, as a direct result of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Bessarabia was annexed by the Soviet Union from Romania, and Chișinău became the capital of the newly created Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Following the Soviet occupation, mass deportations, linked with atrocities, were executed by the NKVD between June 1940 and June 1941. In Chișinău, over 400 people were summarily executed in July 1940 and buried in the grounds of the Metropolitan Palace, the Chișinău Theological Institute, and the backyard of the Italian Consulate, where the NKVD had established its headquarters.[21] As part of the policy of political repression of the potential opposition to the Communist power, tens of thousand members of native families were deported from Bessarabia to other regions of the USSR.

On 10 November 1940, a devastating earthquake occurred. The epicenter of the quake, which measured 7.4 (or 7.7, according to other sources) on the Richter scale, was in Vrancea Mountains and subsequently led to substantial destruction: 78 deaths and 2,795 affected buildings (of which 172 destroyed).[22][23]

In June 1941, in order to recover Bessarabia, Romania entered World War II under the command of the German Wehrmacht, declaring war to the Soviet Union. In the chaos of the Second World War, Chișinău was severely affected. In June–July 1941 the city came under bombardment by Nazi air raids. However, the Romanian and newly Moldovan sources assign most of the responsibility for the damage to Soviet NKVD destruction battalions, that operated in Chișinău until 17 July 1941, when it was captured by Axis forces.[24]

Following the German and Romanian reoccupation, the city suffered from the Nazi extermination policy of its Jewish inhabitants, who were transported on trucks to the outskirts of the city and then summarily shot in partially dug pits. The number of Jews murdered during the initial occupation of the city is estimated at approximately 10,000 people.[25]

As the war drew to a conclusion, the city was once again the scene of heavy fighting as German and Romanian troops retreated. Chișinău was captured by the Red Army on 24 August 1944 as a result of the Jassy-Kishinev Operation.

Soviet period

After the war, Bessarabia was fully reintegrated into the Soviet Union, around 65 percent of its territory as the Moldavian SSR, while the remaining 35 percent were transferred to the Ukrainian SSR.

Two other waves of deportations of Moldova's native population were carried out by the Soviets, the first one immediately after the Soviet reoccupation of Bessarabia until the end of the 1940s, and the second one in the mid-1950s.[26][27]

In the years 1947 to 1949 the architect Alexey Shchusev developed a plan with the aid of a team of architects for the gradual reconstruction of the city.

There was rapid population growth in the 1950s, to which the Soviet administration responded by constructing large-scale housing and palaces in the style of Stalinist architecture. This process continued under Nikita Khrushchev, who called for construction under the slogan "good, cheaper and built faster". The new architectural style brought about dramatic change and generated the style that dominates today, with large blocks of flats arranged in considerable settlements. These Khrushchev-era building are often informally called Khrushchyovka.

The period of the most significant redevelopment of the city extended from 1971, when the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union adopted a decision "On the measures for further development of the city of Kishinev", which secured more than one billion rubles in investment from the state budget,[28] which continued until the independence of Moldova in 1991. The share of dwellings built during the Soviet period (1951–1990) represents 74.3 percent of total households.[29]

On 4 March 1977, the city was again jolted by a devastating earthquake. Several people were killed and panic broke out.

After independence

Many streets of Chișinău are named after historic persons, places or events. Independence from the Soviet Union was followed by a large-scale renaming of streets and localities from a Communist theme into a national one.

Geography

Chișinău is located on the river Bâc, a tributary of the Dniester, at 47°0′N 28°55′E, with an area of 120 km2 (46 sq mi). The municipality comprises 635 km2 (245 sq mi).

The city lies in central Moldova and is surrounded by a relatively level landscape with very fertile ground.

Climate

.jpg)

Chișinău has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa) characterised by warm summers and cool, windy winters. Winter minimum temperatures are often below 0 °C (32 °F), although they rarely drop below −10 °C (14 °F). In summer, the average maximum temperature is approximately 25 °C (77 °F), however, temperatures occasionally reach 35 to 40 °C (95 to 104 °F) in mid-summer in downtown. Although average precipitation and humidity during summer is relatively low, there are infrequent yet heavy storms.

Spring and autumn temperatures vary between 16 to 24 °C (61 to 75 °F), and precipitation during this time tends to be lower than in summer but with more frequent yet milder periods of rain.

| Climate data for Chișinău (1981–2010, extremes 1886–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.5 (59.9) |

20.7 (69.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

35.9 (96.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

39.4 (102.9) |

39.2 (102.6) |

37.3 (99.1) |

32.6 (90.7) |

23.6 (74.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

2.6 (36.7) |

8.1 (46.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.2 (81.0) |

21.5 (70.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

7.4 (45.3) |

2.2 (36.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.9 (28.6) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.7 (71.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

10.5 (50.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.3 (24.3) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.2 (32.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

16.9 (62.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

6.4 (43.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28.4 (−19.1) |

−28.9 (−20.0) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−21.6 (−6.9) |

−22.4 (−8.3) |

−28.9 (−20.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36 (1.4) |

31 (1.2) |

34 (1.3) |

40 (1.6) |

50 (2.0) |

66 (2.6) |

65 (2.6) |

55 (2.2) |

50 (2.0) |

42 (1.7) |

39 (1.5) |

40 (1.6) |

548 (21.6) |

| Average rainy days | 8 | 7 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 132 |

| Average snowy days | 13 | 13 | 8 | 1 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 5 | 11 | 51 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 78 | 71 | 63 | 60 | 63 | 62 | 60 | 66 | 73 | 81 | 83 | 70 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 75 | 80 | 125 | 187 | 254 | 283 | 299 | 295 | 226 | 169 | 75 | 58 | 2,126 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source: Pogoda.ru.net,[30] NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[31] and Weather Atlas[32] | |||||||||||||

Law and government

Municipality

Moldova is administratively subdivided into 3 municipalities, 32 districts, and 2 autonomous units. With a population of 662,836 inhabitants (as of 2014), the Municipality of Chișinău (which includes the nearby communities) is the largest of these municipalities.[33]

Besides the city itself, the municipality comprises 34 other suburban localities: 6 towns (containing further 2 villages within), and 12 communes (containing further 14 villages within). The population, as of 2014 census,[8] is shown in brackets:

Cities/towns

Communes

- Băcioi (10,175)

- Brăila

- Frumușica

- Străisteni

- Bubuieci (8,047)

- Bîc

- Humulești

- Budești (4,928)

- Văduleni

- Ciorescu (5,961)

- Făurești

- Goian

- Colonița (3,367)

- Condrița (595)

- Cruzești (1,815)

- Ceroborta

- Ghidighici (5,051)

- Grătiești (6,183)

- Hulboaca

- Stăuceni (8,694)

- Goianul Nou

- Tohatin (2,596)

- Buneți

- Cheltuitori

- Trușeni (10,380)

- Dumbrava

Administration

Chișinău is governed by the City Council and the City Mayor (Romanian: Primar), both elected once every four years.

His predecessor was Serafim Urechean. Under the Moldovan constitution, Urechean — elected to parliament in 2005 — was unable to hold an additional post to that of an MP. The Democratic Moldova Bloc leader subsequently accepted his mandate and in April resigned from his former position. During his 11-year term, Urechean committed himself to the restoration of the church tower of the Catedrala Nașterea Domnului and improvements in public transport.

Local government

The municipality in its totality elects a mayor and a local council, which then name five pretors, one for each sector. They deal more locally with administrative matters. Each sector claims a part of the city and several suburbs:[34]

Economy

Historically, the city was home to fourteen factories in 1919.[20] Chișinău is the financial and business capital of Moldova. Its GDP comprises about 60% of the national economy[35] reached in 2012 the amount of 52 billion lei (US$4 billion). Thus, the GDP per capita of Chișinău stood at 227% of the Moldova's average. Chișinău has the largest and most developed mass media sector in Moldova, and is home to several related companies ranging from leading television networks and radio stations to major newspapers. All national and international banks (15) have their headquarters located in Chișinău.

Notable sites around Chișinău include the cinema Patria, the new malls Malldova, Megapolis Mall and best-known retailers, such as N1, Fidesco, Green Hills, Fourchette and Metro. While many locals continue to shop at the bazaars, many upper class residents and tourists shop at the retail stores and at Malldova. Elăt, an older mall in the Botanica district, and Sun City, in the center, are more popular with locals.

Several amusement parks exist around the city. A Soviet era one is located in the Botanica district, along the three lakes of a major park, which reaches the outskirts of the city center. Another, the modern Aventura Park, is located farther from the center. A circus, which used to be in a grand building in the Râșcani sector, has been inactive for several years due to a poorly funded renovation project.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1812[36] | 7,000 | — |

| 1818[36] | 10,966 | +56.7% |

| 1835[36] | 34,079 | +210.8% |

| 1847[36] | 43,965 | +29.0% |

| 1851 | 58,849 | +33.9% |

| 1865 | 94,047 | +59.8% |

| 1897(c)[37] | 108,483 | +15.3% |

| 1912 | 121,000 | +11.5% |

| 1930(c)[37] | 114,896 | −5.0% |

| 1950 | 134,000 | +16.6% |

| 1963 | 253,500 | +89.2% |

| 1980 | 519,200 | +104.8% |

| 1991 | 676,700 | +30.3% |

| 2004(c)[38] | 589,446 | −12.9% |

| 2014(c)[3] | 532,513 | −9.7% |

| 2017(e)[39] | 685,900 | +28.8% |

| c-census; e-estimate | ||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1959 | 258,910 | — |

| 1970 | 415,956 | +60.7% |

| 1979 | 589,140 | +41.6% |

| 1989 | 770,948 | +30.9% |

| 2004 | 712,218 | −7.6% |

| 2017 | 820,500 | +15.2% |

| Source: [5] | ||

According to the results of the last Moldovan census, conducted in May 2014, 532,513 inhabitants live within the Chișinău city limits. This represents a 9.7% drop in the number of residents compared to the results of the 2004 Census.

Natural statistics (2015):[40]

Population by sector:

| Sector | Population (2004 cen.)[40] | Population (2015 est.)[40] |

|---|---|---|

| Botanica | 156,633 | 220,000 |

| Buiucani | 107,744 | 160,100 |

| Centru | 90,494 | 110,300 |

| Ciocana | 101,834 | 152,000 |

| Râșcani | 132,740 | 162,493 |

Ethnic composition

| Ethnic group1 | Population | % of total* |

|---|---|---|

| Moldovans2 | 304,816 | 67.17% |

| Romanians2 | 65,573 | 14.45% |

| Russians | 42,157 | 9.29% |

| Ukrainians | 26,955 | 5.94% |

| Bulgarians | 4,810 | 1.06% |

| Gagauz | 3,085 | 0.68% |

| Others | 6,398 | 1.41% |

Footnotes:

1Source: 2014 census results These percentages are for the 469,402 reviewed citizens in the 2014 census that answered the ethnicity question. | ||

Languages

The following table details the population in the Municipality of Chișinău, by native language, as reported in the 2014 Census.

| Maternal language1 | % of total population |

|---|---|

| Romanian2 | 43.4% |

| Moldovan2 | 33.0% |

| Russian | 21.0% |

| Ukrainian | 1.7% |

| Bulgarian | 0.4% |

| Gagauz | 0.3% |

| Others | 0.4% |

Footnotes:

1Source: 2014 census results | |

Religion

Chișinău is the seat of the Moldovan Orthodox Church, as well as of the Metropolis of Bessarabia. The city has multiple churches and synagogues.[20]

- Christians – 90.0%

- Orthodox Christians – 88.4%

- Protestant – 1.2%

- Baptists – 0.6%

- Evangelicals – 0.4%

- Pentecostals – 0.2%

- Seventh-day Adventists – 0.1%

- Roman Catholics – 0.4%

- Other – 1.0%

- No religion – 1.4%

- Atheists – 1.5%

- Undeclared – 6.1%

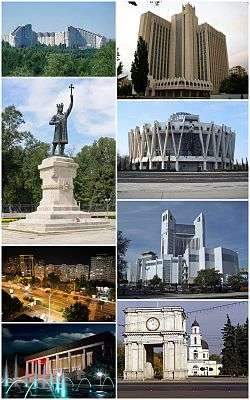

Cityscape

Architecture

Chișinău's growth plan was developed in the 19th century. In 1836 the construction of the Kishinev Cathedral and its belfry was finished. The belfry was demolished in Soviet times and was rebuilt in 1997. Chișinău also displays a tremendous number of orthodox churches and 19th-century buildings around the city such as Ciuflea Monastery or the Transfiguration Church. Much of the city is made from limestone dug from Cricova, leaving a famous wine cellar there.

Many modern-style buildings have been built in the city since 1991. There are many office and shopping complexes that are modern, renovated or newly built, including Kentford, SkyTower, and Unión Fenosa headquarters. However, the old Soviet-style clusters of living blocks are still an extensive feature of the cityscape.

Culture and education

Tourism

The city is home to 12 public and 11 private universities, the Academy of Sciences of Moldova, a number of institutions offering high school and 1–2 years of college education. In Chișinău there are several museums. The three national museums are the National Museum of Ethnography & Natural History, the National Museum of Arts and the National Museum of Archaeology & History.

Triumphal Arch and Nativity Cathedral

Triumphal Arch and Nativity Cathedral Capitoline Wolf and National History Museum

Capitoline Wolf and National History Museum._(18325717946).jpg) Waterfall Steps at the Mill Valley Park

Waterfall Steps at the Mill Valley Park

Organ Hall

Organ Hall

Events and festivals

Chișinău, as well as Moldova as a whole, still show signs of ethnic culture. Signs that say "Patria Mea" (English: My homeland) can be found all over the capital. While few people still wear traditional Moldavian attire, large public events often draw in such original costumes.

Moldova National Wine Day and Wine Festival take place every year in the first weekend of October, in Chișinău. The events celebrate the autumn harvest and recognises the country's long history of winemaking, which dates back some 500 years.[41][42]

In popular culture

The city is the main setting of the 2016 Netflix film Spectral, which takes place in the near future during the fictional Moldovan War.

Media

The majority of Moldova's media industry is based in Chișinău. There are almost 30 FM-radio stations and 10 TV-channels broadcasting in Chișinău. The first radio station in Chișinău, Radio Basarabia, was launched by the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Company on 8 October 1939, when the religious service was broadcast on air from the Nativity Cathedral. The first TV station in the city, Moldova 1, was launched on 30 April 1958, while Nicolae Lupan was serving as the redactor-in-chief of TeleRadio-Moldova.[43]

The state national broadcaster in the country is the state-owned Moldova 1, which has its head office in the city. The broadcasts of TeleradioMoldova have been criticised by the Independent Journalism Center as showing 'bias' towards the authorities.[44]

Other TV channels based in Chișinău are Pro TV Chișinău, PRIME, Jurnal TV, Publika TV, CTC, DTV, Euro TV, TV8, etc. In addition to television, most Moldovan radio and newspaper companies have their headquarters in the city. Broadcasters include the national radio Vocea Basarabiei, Prime FM, BBC Moldova, Radio Europa Libera, Kiss FM Chișinău, Pro FM Chișinău, Radio 21, Fresh FM, Radio Nova, Russkoye Radio, Hit FM Moldova, and many others.

The biggest broadcasters are SunTV, StarNet (IPTV), Moldtelecom (IPTV), Satellit and Zebra TV. In 2007 SunTV and Zebra launched digital TV cable networks.

Politics

| Year | AEI | PCRM |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 54.22% 234,156 | 40.19% 173,570 |

| July 2009 | 56.20% 215,443 | 41.23% 158,034 |

| April 2009 | 47.99% 176,742 | 42.43% 153,227 |

Electoral and political Chișinău given a higher priority for the center-right parties, in principle AEI. PCRM the main opposition party, has a large percentage in the city, but its support base in the city is dwindling.

Elections

| Parties and coalitions | Votes | % | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova | 173,570 | 40.19 | −1.04 | |

| Liberal Democratic Party of Moldova | 122,845 | 28.44 | +11.55 | |

| Liberal Party | 69,266 | 16.04 | −7.10 | |

| Democratic Party of Moldova | 35,369 | 8,19 | -2.36 | |

| Party Alliance Our Moldova | 6,676 | 1.15 | −4.47 | |

| Other Party (<1.0%) | 24,259 | 5.59 | +3.02 | |

| Total (turnout 67.59%) | 433,974 | 100.00 | ||

Transport

Airport

Chișinău International Airport offers connections to major destinations, within Europe and Asia.

Air Moldova and Fly-One airlines have their headquarters, and Wizz-Air has its hub on the grounds of Chișinău International Airport.[45]

Road

The most popular form of internal transport in Moldova is generally the bus. Although the city has just three main terminals, buses generally serve as the means of transport between cities in and outside of Moldova. Popular destinations include Tiraspol, Odessa (Ukraine), Iași and Bucharest (Romania).

Rail

The second most popular form of domestic transportation within Moldova is via railways. The total length of the network managed by Moldovan Railway CFM (as of 2009) is 1,232 kilometres (766 miles). The entire network is single track and is not electrified. The central hub of all railways is Chișinău Central Railway Station. There is another smaller railway station – Revaca located on the city's ends.

Chișinău Railway Station has an international railway terminal with connections to Bucharest, Kiev, Minsk, Odessa, Moscow, Samara, Varna and St. Petersburg. Due to the simmering conflict between Moldova and the unrecognised Transnistria republic the rail traffic towards Ukraine is occasionally stopped.

Public transport

Trolleybuses

There is wide trolleybus network operating as common public transportation within city. From 1994, Chișinău saw the establishment of new trolleybus lines, as well as an increase in capacity of existing lines, to improve connections between the urban districts. The network comprises 22 trolleybus lines being 246 km (153 mi) in length. Trolleybuses run between 05:00 and 03:00. There are 320 units daily operating in Chișinău. However the requirements are as minimum as 600 units. Trolleybus ticket costs at about 2 lei (ca. $0.11). It is the cheapest method of transport within Chișinău municipality.

Buses

There are 29 lines of buses within Chișinău municipality. At each public transportation stops there is attached a schedule for buses and trolleybuses. There are approximately 330 public transportation stops within Chișinău municipality. There is a big lack of buses inside city limits, with only 115 buses operating within Chișinău.[46]

Minibuses

In Chișinău and its suburbs, privately operated minibuses known as "rutieras" generally follow the major bus and trolleybus routes and appear more frequently.[47] As of October 2017, there are 1100 units of minibuses operating within Chișinău. Minibuses services are priced the same as buses – 3 lei for a ticket (ca. $0.18).[48]

Traffic

The city traffic becomes more congested as each year passes. Nowadays there are about 300,000 cars in the city plus 100,000 transit transports coming to the city each day. The number of personal transports is expected to reach 550,000 (without transit) by 2025..

Sport

There are three professional football clubs in Chișinău: Zimbru and Academia of the Moldovan National Division (first level), and Real Succes of the Moldovan "A" Division (second level). Of the larger public multi-use stadiums in the city is the Stadionul Dinamo (Dinamo Stadium), which has a capacity of 2,692. The Zimbru Stadium, opened in May 2006 with a capacity of 10,500 sitting places, meets all the requirements for holding official international matches, and was the venue for all Moldova's Euro 2008 qualifying games. There are discussions to build a new olympic stadium with capacity of circa 25,000 seats, that would meet all international requirements. Since 2011 CS Femina-Sport Chișinău has organised women's competitions in seven sports.

Notable people

Natives

- Andrew Rayel, Stage name of Andrei Rață, Moldovan DJ

- Alexander Ulanovsky, the chief illegal "rezident" for Soviet Military Intelligence (GRU), prisoner in the Soviet gulag

- Olga Bancic, known for her role in the French Resistance during World War II

- Maria Cebotari, Romanian soprano and actress, one of Europe's greatest opera stars in the 1930s and 1940s

- William F. Friedman, American cryptologist

- Sarah Gorby, French-Jewish singer

- Anatole Jakovsky, French art critic

- Avigdor Lieberman, Israeli politician

- Boris Mints – Russian billionaire

- Lewis Milestone, American motion picture director

- Sacha Moldovan, American expressionist and post-impressionist painter

- Ilya Oleynikov, comic actor and television personality

- Nina Pekerman, Israeli triathlete

- Maria Winetzkaja, American opera singer in the 1910s–1920s

- Sam Zemurray, American businessman who made his fortune in the banana trade

Residents

- Gheorghe Botezatu American engineer, businessman and pioneer of helicopter flight

- Eugen Doga, composer

- Israel Gohberg, Soviet and Israeli mathematician

- Dovid Knut, poet and member of the French Resistance

- Sigmund Mogulesko, singer, actor, and composer

- SunStroke Project, Moldovan representative for both the Eurovision Song Contest 2010 and the Eurovision Song Contest 2017

- Zlata Tkach, composer and music educator

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Chișinău is twinned with:[49]

Notes and references

- Brezianu, Andrei; Spânu, Vlad (2010). The A to Z of Moldova. Scarecrow Press. p. 81. ISBN 9781461672036. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- "Planul Urbanistic General al Municipiului Chișinău" (Press release). Chișinău City Hall. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- "Principalele rezultate ale RPL 2014" (Press release). National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- https://statbank.statistica.md/pxweb/pxweb/ro/60%20Statistica%20regionala/60%20Statistica%20regionala__02%20POP/POP010300reg.px/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=b2ff27d7-0b96-43c9-934b-42e1a2a9a774

- http://statbank.statistica.md/pxweb/pxweb/en/60%20Statistica%20regionala/60%20Statistica%20regionala__02%20POP/POP010300reg.px/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=2345d98a-890b-4459-bb1f-9b565f99b3b9

- http://www.statistica.md/public/files/publicatii_electronice/Chisinau/Anuar_Chisinau_2013.pdf

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "Population by commune, sex and age groups" (Press release). National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- http://www.natura2000oltenita-chiciu.ro/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Moldova-Pitoreasca-Picturesque-Moldavia-pdf-Vladimir-Toncea.pdf

- (in Romanian) History of Chișinău Archived 22 July 2003 at the Wayback Machine on Kishinev.info, Retrieved on 12 October 2008

- "Istoria Orașului I" (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2010.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Transindex – Határon túli magyar helységnévszótár". Sebok2.adatbank.transindex.ro. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Racz Anita" (PDF). Mnytud.arts.unideb.hu. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Zamfir C. Arbure (1 January 1898). "Basarabia in secolul XIX ..." C. Göbl – via Internet Archive.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition

- "The Jewish Community of Kishinev". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- Penkower, Monty Noam (10 September 2004). "The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903: A Turning Point in Jewish History". Modern Judaism. 24 (3): 187–225 – via Project MUSE.

- Encyclopaedia Judaica, Vol 10, page 1066. Jerusalem, 1971.

- "VIRTUAL KISHINEV – 1903 Pogrom". Kishinev.moldline.net. 19 August 1905. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Kaba, John (1919). Politico-economic Review of Basarabia. United States: American Relief Administration. p. 12.

- Andrei Brezianu; Vlad Spânu (26 May 2010). The A to Z of Moldova. Scarecrow Press. pp. 116–. ISBN 978-0-8108-7211-0.

- Building Damage vs. Territorial Casualty Patterns during the Vrancea (Romania) Earthquakes of 1940 and 1977

- "75 de ani de la cutremurul din 1940". 10 November 2015.

- Virgil Pâslariuc. "Cine a devastat Chișinăul în iulie 1941?" Historia.ro (in Romanian)

- "Memories of the Holocaust: Kishinev (Chișinău) (1941–1944)", jewishvirtuallibrary.org

- invitat, Autor (15 June 2011). "70 years ago today: 13–14 June 1941, 300,000 were deported from Bessarabia".

- "Stalin's Ethnic Deportations—and the Gerrymandered Ethnic Map". 8 October 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Energy consumption in households". Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- "Климат Кишинева (Climate of Chișinău)" (in Russian). Погода и климат. May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "Kisinev Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- d.o.o, Yu Media Group. "Chisinau, Moldova - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Moldovan Law 764-XV from 27 December 2001, Monitorul Oficial al Republicii Moldova, no. 16/53, 29 December 2001

- Moldovan Law 431-XIII from 19 April 1995 Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Monitorul Oficial al Republicii Moldova, no. 31-32/340, 9 June 1995 (in Romanian)

- "CHIŞINĂU ÎN CIFRE : ANUAR STATISTIC" (PDF). Statistica.md. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Evoluţia demografică a oraşelor basarabene în prima jumătate a secolului al XIX-lea". Bessarabia.ru. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Jewish Population in Bessarabia and Transnistria – Geographical". Jewishgen.org. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Statistics, National Bureau of (30 September 2009). "// Population Census 2004".

- "Populatia stabila pe orase si raioane, la 1 ianuarie, 2005–2017" [Permanent population in cities and districts on 1 January 2005–2017]. National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova. Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- "Chisinau in cifre. Anuar statistic 2012" (PDF) (Press release). National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova.

- "Moldova's 'National Wine Day'". Rferl.org. 8 October 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "National Wine Day in Chisinau". Moldova-online.travel. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Monitoring of programs on Radio Moldova and TV Moldova 1" (PDF). Archived from the original on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2006.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Air Moldova :: Contacts". Airmoldova.md. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Numărul de troleibuze şi autobuze care vor circula în Chișinău a fost majorat – #diez".

- "Chisinau." Chisinau Infos. World Infos, n.d. Web. 9 November 2016.

- "Numărul microbuzelor care circulă pe itinerarele din capitală s-a micșorat cu 600 de unități". Moldpres. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- "Orașe înfrățite (Twin cities of Chișinău) [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Romanian). Primăria Municipiului Chișinău. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "Partner und Freundesstädte". Stadt Mannheim (in German). Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- Jérôme Steffenino, Marguerite Masson. "Ville de Grenoble –Coopérations et villes jumelles". Grenoble.fr. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- listed on Yerevan Municipality Official Website as Kishinev.

- "Yerevan – Twin Towns & Sister Cities". Yerevan Municipality Official Website. © 2005–2013 http://www.yerevan.am. Retrieved 4 November 2013. External link in

|publisher=(help) - "Twin towns and Sister cities of Minsk [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Russian). The department of protocol and international relations of Minsk City Executive Committee. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "Kardeş Kentleri Listesi ve 5 Mayıs Avrupa Günü Kutlaması [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Turkish). Ankara Büyükşehir Belediyesi – Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

Further reading

- Hamm, Michael F. (March 1998). "Kishinev: The character and development of a Tsarist Frontier Town". Nationalities Papers. 26 (1): 19–37. doi:10.1080/00905999808408548.