Tiraspol

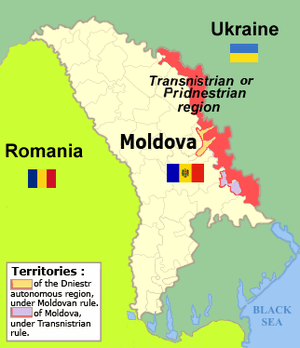

Tiraspol (Russian: Тирасполь [tʲɪˈraspəlʲ]; Ukrainian: Тираспіль[3] [tɪˈrɑspilʲ]) is internationally recognised as the second largest city in Moldova, but is effectively the capital and administrative centre of the unrecognised Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Pridnestrovie). The city is located on the eastern bank of the Dniester River. Tiraspol is a regional hub of light industry, such as furniture and electrical goods production.

Tiraspol Тирасполь | |

|---|---|

Municipality | |

.jpg)  .jpg) Central street of Tiraspol | |

Flag | |

Tiraspol Location of Tiraspol in Transnistria | |

| Coordinates: 46°50′25″N 29°38′36″E | |

| Country (de jure) | Moldova |

| Country (de facto) | Transnistria[1] |

| Government | |

| • Head of the State Administration of Tiraspol | Andrey Bezbabchenko[2] |

| Elevation | 26 m (85 ft) |

| Population (2015) | |

| • Total | 133,807 |

| Area code(s) | + 373 533 |

The modern city of Tiraspol was founded by the Russian generalissimo Alexander Suvorov in 1792, although the area had been inhabited for thousands of years by varying ethnic groups.[4] The city celebrates its anniversary every year on 14 October.[5]

Etymology

The toponym consists of two ancient Greek words: Τύρας, Tyras, the Ancient name for the Dniester River, and polis, i.e., a city (state).

History

Classical history

Tyras (Τύρας), also spelled Tiras, was a colony of the Greek city Miletus, probably founded about 600 BC, situated some 10 kilometres (6 miles) from the mouth of the Tiras River (Dniester). Of no great importance in early times, in the 2nd century BC it fell under the dominion of indigenous kings whose names appear on its coins. It was destroyed by the Thracian Getae about 50 BC.

In 56 AD the Romans restored the city and made it part of the colonial province of Lower Moesia. A series of its coins exist that feature heads of Roman emperors from Domitian to Severus Alexander. Soon after the time of the latter, the city was destroyed again, this time by the invasion of the Goths. Its government was in the hands of five archons, a senate, a popular assembly and a registrar. The images on its coins from this period suggest a trade in wheat, wine and fish. The few inscriptions extant are mostly concerned with trade.

Such ancient archeological remains are scanty, as the city site was built over by the great medieval fortress of Monocastro or Akkerman.[6] During the Middle Ages, the area around Tiraspol was a buffer zone between the Tatars and the Moldavians, and inhabited by both ethnic groups.

Russian foundation

The Russian Empire conquered its way to the Dniester River, taking territory from the Ottoman Empire. In 1792 the Russian army built fortifications to guard the western border near a Moldavian village named Sucleia. Field Marshal Alexander Suvorov is considered the founder of modern Tiraspol; his statue is the city's most distinctive landmark. The city took its name from Tyras, the Greek name of the Dniester River on which it stands.

In 1828 the Russian government established a customs house in Tiraspol to try to suppress smuggling. The customs house was subordinated to the chief of the Odessa customs region. It began operations with 14 employees. They inspected shipments of bread, paper, oil, wine, sugar, fruits and other goods.

Soviet Tiraspol

After the Russian Revolution, the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was created in Ukraine in 1924, with Balta as its capital. The republic had Romanian, Ukrainian and Russian as its official languages. Its capital was moved in 1929 to Tiraspol, which remained the capital of the Moldavian ASSR until 1940.

In 1940, following the secret provisions of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the USSR forced Romania to cede Bessarabia. It integrated Tiraspol, until then part of the Ukrainian SSR, into the newly formed Moldavian SSR. On 7 August 1941, following the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, the city was taken over by Romanian troops. During the occupation, Tiraspol was under Romanian administration. During that period almost all of its Jewish population died: they were slain in situ or deported to German Nazi death camps, where they were murdered.

In 1941 before the occupation, the newspaper Dnestrovskaya Pravda was founded by the Tiraspol City Council of popular deputies. This is the oldest periodical publication in the region. On 12 April 1944, the city was retaken by the Red Army and became again part of Moldavian SSR.

Post-independence

On 27 January 1990, the citizens in Tiraspol passed a referendum declaring the city as an independent territory. The nearby city of Bendery also declared its independence from Moldova. As the Russian-speaking independence movement gained momentum, some local governments banded together to resist pressure from the Moldovan government for nationalization.

On 2 September 1990, Tiraspol was proclaimed the capital of the new Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. The new republic was not officially recognized by Soviet authorities; however, it received support from some important Soviet leaders, such as Anatoly Lukyanov. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the territory east of the Dniester River declared independence as the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR), with Tiraspol as its capital. It was not recognized by the international community.

On 1 July 2005, the Lucian Blaga Lyceum, a high school with Romanian as its language of instruction, was registered as a Pridnestrovian non-governmental establishment. The registration of six Romanian language schools has been the subject of negotiations with the government since 2000. The tension increased in the summer of 2004, when the Pridnestrovian authorities forcibly closed the schools that used the Moldovan language in the Latin script. According to the official PMR view, this is considered as Romanian. Moldovan, written in the Cyrillic script, is one of the three official languages in the PMR; Romanian is not. Some economic measures and counter-measures were taken on both banks of the Dniester.

Tensions have been expressed in terrorist incidents. On 6 July 2006, an explosion, believed to be caused by a bomb, killed at least eight people in a minibus.[7] On 13 August 2006, a grenade explosion in a trolleybus killed two and injured ten.[8][9][10]

Geography and climate

Tiraspol features a humid continental climate that closely borders an oceanic climate and has transitional features of the humid subtropical climate due to its warm summers. Summers are mild, with average monthly temperatures at around 21 °C (70 °F) in July and August. Winters are cold, with average temperatures in the coldest month (January) at −2.7 °C (27 °F). Precipitation is relatively evenly spread throughout the year, though there is a noticeable increase in monthly precipitation in June and July. Tiraspol on average sees nearly 500 mm (20 in) of precipitation per year.

| Climate data for Tiraspol | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

2.3 (36.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

16.1 (61.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

3.3 (37.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.1 (21.0) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

5.1 (41.2) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33 (1.3) |

35 (1.4) |

28 (1.1) |

35 (1.4) |

52 (2.0) |

72 (2.8) |

63 (2.5) |

49 (1.9) |

38 (1.5) |

26 (1.0) |

36 (1.4) |

38 (1.5) |

495 (19.5) |

| Average precipitation days | 11 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 116 |

| Source: World Weather Information Service[11] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Population

The population of the city was about 190,000 in 1989 and about 203,000 in 1992. 41% were Russians, 32% Ukrainians (both Eastern Slavic) and 18% were Moldovans (ethnically akin to Romanians).

As result of the political and economic situation that followed the proclamation of the independent (unrecognized) Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic, as well as large Jewish emigration in the early 1990s, the population of the city fell below its 1989 number and the 2004 Census in Transnistria put its population at 158,069.[12]

Religion

The Latin Catholic minority was served by its own Roman Catholic Diocese of Tiraspol (originally called Cherson), which at times also covered part of neighbouring Romania and Russia, until its 2002 suppression and merger into the Russian Diocese of Saint Clement at Saratov.

Culture

.jpg)

The statue of Alexander Suvorov was erected in the central square in 1979 in commemoration of his 250th anniversary. In front of the Pridnestrovian Government building there is a statue of Vladimir Lenin. On the opposite side of the central square, a monument plaza features a Soviet T-34 tank, commemorating the Soviet victory in World War II, an eternal flame to those who fell defending the city in 1941 and liberating it in 1944, as well as several monuments dedicated to more recent conflicts, including the Soviet–Afghan War and the War of Transnistria.

Sport

The two main football clubs are Sheriff Tiraspol and FC Tiraspol. Sheriff is the most successful Moldovan football club of recent history, winning 14 league titles since the 2000–2001 season, and 6 Moldovan Cups. A third club, CS Tiligul-Tiras Tiraspol, withdrew from competition prior to the 2009–2010 season. Tiraspol is home to the Sheriff Stadium, the largest capacity stadium in the region, with a capacity of 14,300 seats.

Notable people

.jpg)

- Nikolay Zelinsky (1861 in Tiraspol – 1953 in Moscow) Russian and Soviet chemist, academician of the Academy of Sciences of USSR, invented the first effective filtering activated charcoal gas mask

- Georgi Stamatov (1869 in Tiraspol – 1942 in Sofia) was a Bulgarian writer.

- Mikhail Larionov (1881 in Tiraspol – 1964) was an avant-garde Russian painter.

- Abraham Rabinovitch (1889 in Tiraspol – 1964 in New South Wales) was an Australian-Russian property developer and pioneer of the Sydney Modern Orthodox Jewish community; emigrated to Australia in 1915

- Gheorghe Pintilie (born 1902 in Tiraspol – 1985) was a Soviet intelligence agent, Russian citizen and naturalised Romanian communist activist of Ukrainian origin and the first Director of the Securitate

- Izrail Shmurun (1912 in Tiraspol – 1985 in Chișinău) a Moldavian Soviet architect

- Larisa Eryomina (born 1950 in Tiraspol) a stage and screen actress, particularly in Soviet films of the 1970s.

- Oxana Ionova (born 1966 in Tiraspol) was the head of the state tax service of Pridnestrovie and director of Pridnestrovie's central bank from 2008 to 2011, subsequently charged with embezzlement of Russian humanitarian aid and state property, illegal business practices, abuse of power and forgery.

- Vlad Stashevsky (born 1974 in Tiraspol) is a Russian pop singer.

- Sergey Stepanov (born 1984 in Tiraspol) musician and composer from Pridnestrovie, member of the SunStroke Project

- Valeria Lukyanova (born 1985 in Tiraspol) is a Ukrainian model and entertainer, famous for her resemblance to a Barbie doll, lives in Moscow.

Politics

- Serhiy Kivalov (born 1954 in Tiraspol) is Ukrainian politician, jurist, parliamentarian, head of Central Election Commission

- Vladimir Mikhailovich Belyaev (born 18 March 1965 in Tiraspol) is the minister of information and telecommunications

- Maya Parnas (born 1974 in Tiraspol) politician and was the former acting Prime Minister of Pridnestrovie

- Nina Shtanski (born 1977 in Tiraspol) – former Pridnestrovian state politician, the Minister of Foreign Affairs 2012 to 2015

- Roman Khudyakov (born 1977 in Tiraspol) is a Pridnestrovian-born Russian politician, chairman of the Liberal Democratic Party of Pridnestrovie

- Vladimir Yastrebchak (born 1979 in Tiraspol) the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Pridnestrovie from 2008 to 2012.

- Olga Paterova (born in 1984 in Tiraspol) a young politician, the press secretary for the political youth organization Breakthrough

- Yury Cheban, Pridnestrovian Minister of Natural Resources and Ecological Control

Sport

- Constantin Nour (1906 or 1907 in Tiraspol – 1986) was a Romanian champion middleweight boxer and national team trainer

- Igor Samoilenco (born 1977 in Tiraspol) retired male boxer from Moldova

- Larisa Popova (born 1957 in Tiraspol) Moldovan rower who competed for the Soviet Union in the 1976 Summer Olympics

- Andrei Mihailov (born 1980 in Tiraspol) former backstroke swimmer, competed in the 2000 and the 2004 Summer Olympics

- Andrei Corneencov (born 1982 in Tiraspol) former Moldovan international footballer.

- Stanislau Tsivonchyk (born 1985 in Tiraspol) a Belarusian pole vaulter, competed in the pole vault at the 2012 Summer Olympics

- Vitalie Bulat (born 1987 in Tiraspol) is a Moldovan footballer

- Oleksandr Kolchenko (born 1988 in Tiraspol) a Ukrainian basketball player for Cherkaski Mavpy and the Ukrainian national team

- Dănilă Artiomov (born 1994 in Tiraspol) is a Moldovan breaststroke swimmer

Gallery

Statue of Alexander Suvorov at Suvorov Square in Tiraspol

Statue of Alexander Suvorov at Suvorov Square in Tiraspol A street in central Tiraspol

A street in central Tiraspol.jpg) The Victory park of Tiraspol

The Victory park of Tiraspol.jpg) Dnestr river passing through Tiraspol

Dnestr river passing through Tiraspol.jpg) Statue of Lenin in front of the parliament building, Tiraspol

Statue of Lenin in front of the parliament building, Tiraspol.jpg) Street scene, Tiraspol

Street scene, Tiraspol.jpg) House of Soviets, Tiraspol

House of Soviets, Tiraspol.jpg) Young man on a Soviet-era tank, Tiraspol

Young man on a Soviet-era tank, Tiraspol.jpg) War memorial and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Tiraspol

War memorial and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Tiraspol.jpg) Tiraspol city centre

Tiraspol city centre.jpg) View along Dniester river, Tiraspol

View along Dniester river, Tiraspol

References

- Notes

- Transnistria's status is disputed. It considers itself to be an independent state, but this is not recognised by any country. The Moldovan government and all the world's other states consider Transnistria de jure a part of Moldova territory.

- State Administrations of Cities and Regions of the PMR

- Ісаєв, Дмитро (2008). Історія України. Ілюстрований атлас [History of Ukraine. An Illustrated Atlas.] (PDF) (in Ukrainian). Kiev: Інститут передових технологій. p. 33. ISBN 978-966-7650-49-0.

- About Transdniestra (Russian) Archived 15 April 2008[Date mismatch] at the Wayback Machine World Window NGO. Retrieved 2006, 12–27

- "Street fairs, celebrations mark Tiraspol's 214th birthday", Tiraspol Times, 14 October 2006. Retrieved 2007, 2–20

- See E. H. Minns, Scythians and Greeks (Cambridge, 1909); V. V. Latyshev, Inscriptiones Orae Septentrionalis Ponti Euxini, vol. I.

- "Trans-Dniester blast kills eight". BBC News. 6 July 2006.

- "Trolley bus blasted in Tiraspol possibly in a terror attack" Archived 30 September 2007[Date mismatch] at the Wayback Machine, Regnum

- "New bus explosion in Tiraspol leaves one dead, eleven injured", Tiraspol Times

- "Another blast in public transport in Tiraspol", Moldpres

- "Weather Information for Tiraspol". World Weather Information Service. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- 2004 Census: PMR urban, multilingual, multicultural, from Pridnestrovie.net.

- Trondheim by – Vennskapsbyer Archived 18 May 2015[Date mismatch] at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Tiraspol (p. 422) at Miriam Weiner's Routes to Roots Foundation

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tiraspol. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tiraspol. |

Non-Pridnestrovian links

Pridnestrovian links

- Tiraspol.info (in Russian)