Gneiss

Gneiss (/ˈnaɪs/) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. Gneiss is formed by high temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Orthogneiss is gneiss derived from igneous rock (such as granite). Paragneiss is gneiss derived from sedimentary rock (such as sandstone). Gneiss forms at higher temperatures and pressures than schist. Gneiss nearly always shows a banded texture characterized by alternating darker and lighter colored bands and without a distinct foliation.

| Metamorphic rock | |

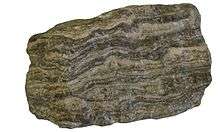

Sample of gneiss exhibiting "gneissic banding". |

Etymology

The word gneiss has been used in English since at least 1757. It is borrowed from the German word Gneis, formerly also spelled Gneiss, which is probably derived from the Middle High German noun gneist "spark" (so called because the rock glitters).[1]

Formation

Gneiss is formed from sedimentary or igneous rock exposed to temperatures greater than 320 °C and relatively high pressure.

Composition

Gneissic rocks are usually medium- to coarse-foliated; they are largely recrystallized but do not carry large quantities of micas, chlorite or other platy minerals. Gneisses that are metamorphosed igneous rocks or their equivalent are termed granite gneisses, diorite gneisses, etc. Gneiss rocks may also be named after a characteristic component such as garnet gneiss, biotite gneiss, albite gneiss, etc. Orthogneiss designates a gneiss derived from an igneous rock, and paragneiss is one from a sedimentary rock.

Gneissose rocks have properties similar to gneiss.

Gneissic banding

Gneiss appears to be striped in bands like parallel lines in shape, called gneissic banding.[2] The banding is developed under high temperature and pressure conditions.

The minerals are arranged into layers that appear as bands in cross section.[2] The appearance of layers, called 'compositional banding', occurs because the layers, or bands, are of different composition. The darker bands have relatively more mafic minerals (those containing more magnesium and iron). The lighter bands contain relatively more felsic minerals (silicate minerals, containing more of the lighter elements, such as silicon, oxygen, aluminium, sodium, and potassium).

A common cause of the banding is the subjection of the protolith (the original rock material that undergoes metamorphism) to extreme shearing force, a sliding force similar to the pushing of the top of a deck of cards in one direction, and the bottom of the deck in the other direction.[2] These forces stretch out the rock like a plastic, and the original material is spread out into sheets.

Some banding is formed from original rock material (protolith) that is subjected to extreme temperature and pressure and is composed of alternating layers of sandstone (lighter) and shale (darker), which is metamorphosed into bands of quartzite and mica.[2]

Another cause of banding is "metamorphic differentiation", which separates different materials into different layers through chemical reactions, a process not fully understood.[2]

Not all gneiss rocks have detectable banding. In kyanite gneiss, crystals of kyanite appear as random clumps in what is mainly a plagioclase (albite) matrix.

Types

Augen gneiss

Augen gneiss, from the German: Augen [ˈaʊɡən], meaning "eyes", is a coarse-grained gneiss resulting from metamorphism of granite, which contains characteristic elliptic or lenticular shear-bound feldspar porphyroclasts, normally microcline, within the layering of the quartz, biotite and magnetite bands.

Henderson gneiss

Henderson gneiss is found in North Carolina and South Carolina, US, east of the Brevard Shear Zone. It has deformed into two sequential forms. The second, more warped, form is associated with the Brevard Fault, and the first deformation results from displacement to the southwest.[3]

Lewisian gneiss

Most of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland have a bedrock formed from Lewisian gneiss. In addition to the Outer Hebrides, they form basement deposits on the Scottish mainland west of the Moine Thrust and on the islands of Coll and Tiree.[5] These rocks are largely igneous in origin, mixed with metamorphosed marble, quartzite and mica schist with later intrusions of basaltic dikes and granite magma.[6]

Archean and Proterozoic gneiss

Gneisses of Archean and Proterozoic age occur in the Baltic Shield.

References

Citations

- Harper, Online Etym. Dict., "gneiss"

- Marshak 2013, pp. 194–95; Figs. 7.6a–c

- Sacks & Secor (1990).

- Bjørn Hageskov (1985): Constrictional deformation of the Koster dyke swarm in a ductile sinistral shear zone, Koster islands, SW Sweden. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark 34(3–4): 151–97

- Gillen (2003), p. 44.

- McKirdy et al. (2007), p. 95.

Bibliography

- Blatt, Harvey and Robert J. Tracy (1996). Petrology: Igneous, Sedimentary and Metamorphic, 2nd ed. Freeman, pp. 359–65. ISBN 0-7167-2438-3.

- Gillen, Con (2003). Geology and landscapes of Scotland. Harpenden. Terra Publishing. ISBN 1-903544-09-2.

- Harper, Douglas (ed.). "gneiss", Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- Marshak, Stephen (2013). Essentials of Geology (4th ed.). W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-91939-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKirdy, Alan, Roger Crofts and John Gordon (2007). Land of Mountain and Flood: The Geology and Landforms of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-357-0.

- Murray, W.H. (1966). The Hebrides. London. Heinemann.

- Sacks, Paul E. and Donald T. Secor (1990). "Kinematics of Late Paleozoic continental collision between Laurentia and Gondwana". Science, 250 (4988): 1702–05. doi:10.1126/science.250.4988.1702.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gneiss. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1906.