Free imperial city

In the Holy Roman Empire, the collective term free and imperial cities (German: Freie und Reichsstädte), briefly worded free imperial city (Freie Reichsstadt, Latin: urbs imperialis libera), was used from the fifteenth century to denote a self-ruling city that had a certain amount of autonomy and was represented in the Imperial Diet.[1] An imperial city held the status of Imperial immediacy, and as such, was subordinate only to the Holy Roman Emperor, as opposed to a territorial city or town (Landstadt) which was subordinate to a territorial prince – be it an ecclesiastical lord (prince-bishop, prince-abbot) or a secular prince (duke (Herzog), margrave, count (Graf), etc.).

Origin

The evolution of some German cities into self-ruling constitutional entities of the Empire was slower than that of the secular and ecclesiastical princes. In the course of the 13th and 14th centuries, some cities were promoted by the emperor to the status of Imperial Cities (Reichsstädte; Urbes imperiales), essentially for fiscal reasons. Those cities, which had been founded by the German kings and emperors in the 10th through 13th centuries and had initially been administered by royal/imperial stewards (Vögte), gradually gained independence as their city magistrates assumed the duties of administration and justice; some prominent examples are Colmar, Haguenau and Mulhouse in Alsace or Memmingen and Ravensburg in upper Swabia.

The Free Cities (Freie Städte; Urbes liberae) were those, such as Basel, Augsburg, Cologne or Strasbourg, that were initially subjected to a prince-bishop and, likewise, progressively gained independence from that lord. In a few cases, such as in Cologne, the former ecclesiastical lord continued to claim the right to exercise some residual feudal privileges over the Free City, a claim that gave rise to constant litigation almost until the end of the Empire.

Over time, the difference between Imperial Cities and Free Cities became increasingly blurred, so that they became collectively known as "Free Imperial Cities", or "Free and Imperial Cities", and by the late 15th century many cities included both "Free" and "Imperial" in their name.[2] Like the other Imperial Estates, they could wage war, make peace, and control their own trade, and they permitted little interference from outside. In the later Middle Ages, a number of Free Cities formed City Leagues (Städtebünde), such as the Hanseatic League or the Alsatian Décapole, to promote and defend their interests.

In the course of the Middle Ages, cities gained, and sometimes — if rarely — lost, their freedom through the vicissitudes of power politics. Some favored cities gained a charter by gift. Others purchased one from a prince in need of funds. Some won it by force of arms[1] during the troubled 13th and 14th centuries and others lost their privileges during the same period by the same way. Some cities became free through the void created by the extinction of dominant families,[1] like the Swabian Hohenstaufen. Some voluntarily placed themselves under the protection of a territorial ruler and therefore lost their independence.

A few, like Protestant Donauwörth, which in 1607 was annexed to the Catholic Duchy of Bavaria, were stripped by the Emperor of their status as a Free City — for genuine or trumped-up reasons. However, this rarely happened after the Reformation, and of the sixty Free Imperial Cities that remained at the Peace of Westphalia, all but the ten Alsatian cities (which were annexed by France during the late 17th century) continued to exist until the mediatization of 1803.

Distinction between free imperial cities and other cities

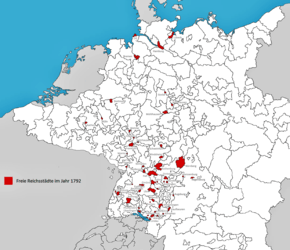

There were approximately four thousand towns and cities in the Empire, although around the year 1600 over nine-tenths of them had fewer than one thousand inhabitants.[3] During the late Middle Ages, fewer than two hundred of these places ever enjoyed the status of Free Imperial Cities, and some of those did so only for a few decades. The Imperial military tax register (Reichsmatrikel) of 1521 listed eighty-five such cities, and this figure had fallen to sixty-five by the time of the Peace of Augsburg in 1555. From the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 to 1803, their number oscillated at around fifty.[notes 1]

Unlike the Free Imperial Cities, the second category of towns and cities, now called "territorial cities"[notes 2] were subject to an ecclesiastical or lay lord, and while many of them enjoyed self-government to varying degrees, this was a precarious privilege which might be curtailed or abolished according to the will of the lord.[4]

Reflecting the extraordinarily complex constitutional set-up of the Holy Roman Empire, a third category, composed of semi-autonomous cities that belonged to neither of those two types, is distinguished by some historians. These were cities whose size and economic strength was sufficient to sustain a substantial independence from surrounding territorial lords for a considerable time, even though no formal right to independence existed. These cities were typically located in small territories where the ruler was weak.[notes 3] They were nevertheless the exception among the multitude of territorial towns and cities. Cities of both latter categories normally had representation in territorial diets, but not in the Imperial Diet.[5][6]

Organization

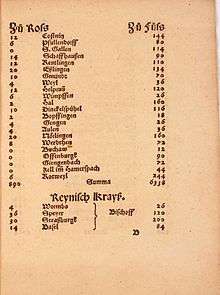

Free imperial cities were not officially admitted as own Imperial Estates to the Imperial Diet until 1489, and even then their votes were usually considered only advisory (votum consultativum) compared to the Benches of the electors and princes. The cities divided themselves into two groups, or benches, in the Imperial Diet, the Rhenish and the Swabian Bench.[1][notes 4]

These same cities were among the 85 free imperial cities listed on the Reichsmatrikel of 1521,[7] the imperial civil and military tax-schedule used for more than a century to assess the contributions of all the Imperial Estates in case of a war formally declared by the Imperial Diet. The military and monetary contribution of each city is indicated in parenthesis (for instance Cologne (30-322-600) means that Cologne had to provide 30 horsemen, 322 footmen and 600 gulden).[8] These numbers are equivalent to one simplum. If need be, the Diet could vote a second and a third simplum, in which case each member's contribution was doubled or tripled. At the time, the Free imperial cities were considered wealthy and the monetary contribution of Nuremberg, Ulm and Cologne for instance were as high as that of the Electors (Mainz, Trier, Cologne, Palatinate, Saxony, Brandenburg) and the Dukes of Württemberg and of Lorraine.

The following list contains the 50 Free imperial cities that took part in the Imperial Diet of 1792. They are listed according to their voting order on the Rhenish and Swabian benches.[9]

Rhenish Bench

Swabian Bench

.png)

By the time of the Peace of Westphalia, the cities constituted a formal third "college" and their full vote (votum decisivum) was confirmed, although they failed to secure parity of representation with the two other colleges. To avoid the possibility that they would have the casting vote in case of a tie between the Electors and the Princes, it was decided that these should decide first and consult the cities afterward.[10][11]

Despite this somewhat unequal status of the cities in the functioning of the Imperial Diet, their full admittance to that federal institution was crucial in clarifying their hitherto uncertain status and in legitimizing their permanent existence as full-fledged Imperial Estates. Constitutionally, if in no other way, the diminutive Free Imperial City of Isny was the equal of the Margraviate of Brandenburg.

Development

Having probably learned from experience that there was not much to gain from active, and costly, participation in the Imperial Diet's proceedings due to the lack of empathy of the princes, the cities made little use of their representation in that body. By about 1700, almost all the cities with the exception of Nuremberg, Ulm and Regensburg (where by then the Perpetual Imperial Diet was located), were represented by various Regensburg lawyers and officials who often represented several cities simultaneously.[12] Instead, many cities found it more profitable to maintain agents at the Aulic Council in Vienna, where the risk of an adverse judgment posed a greater risk to city treasuries and independence.[13]

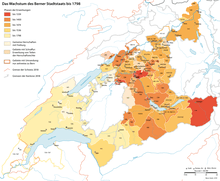

The territory of most Free Imperial Cities was generally quite small but there were exceptions. The largest territories formed in what is now Switzerland with cities like Bern, Zürich and Luzern, but also cities like Ulm, Nuremberg and Hamburg in what is now Germany possessed substantial hinterlands or fiefs that comprised dozens of villages and thousands of subject peasants who did not enjoy the same rights as the urban population. At the opposite end, the authority of Cologne, Aachen, Worms, Goslar, Wetzlar, Augsburg and Regensburg barely extended beyond the city walls.

The constitution of Free and Imperial Cities was republican in form, but in all but the smallest cities, the city government was oligarchic in nature with a governing town council composed of an elite, hereditary patrician class, the so-called town council families (Ratsverwandte). They were the most economically significant burgher families who had asserted themselves politically over time.

Below them, with a say in the government of the city (there were exceptions, such as Nuremberg, where the patriciate ruled alone), were the citizens or burghers, the smaller, privileged section of the city's permanent population whose number varied according to the rule of citizenship of each city. To the common town dweller – whether he lived in a prestigious Free Imperial City like Frankfurt, Augsburg or Nuremberg, or in a small market town such as there were hundreds throughout Germany – attaining burgher status (Bürgerrecht) could be his greatest aim in life. The burgher status was usually an inherited privilege renewed pro-forma in each generation of the family concerned but it could also be purchased. At times, the sale of burgher status could be a significant item of town income as fiscal records show. The Bürgerrecht was local and not transferable to another city.

The burghers were usually the lowest social group to have political power and privilege within the Holy Roman Empire. Below them was the disenfranchised urban population, maybe half of the total in many cities, the so-called "residents" (Beisassen) or "guests": smaller artisans, craftsmen, street venders, day laborers, servants and the poor, but also those whose residence in the city was temporary, such as wintering noblemen, foreign merchants, princely officials, and so on.[14]

Urban conflicts in Free Imperial Cities, which sometimes amounted to class warfare, were not uncommon in the Early Modern Age, particularly in the 17th century (Lübeck, 1598–1669; Schwäbisch Hall, 1601–1604; Frankfurt, 1612–1614; Wezlar, 1612–1615; Erfurt, 1648–1664; Cologne, 1680–1685; Hamburg 1678–1693, 1702–1708).[15] Sometimes, as in the case of Hamburg in 1708, the situation was considered sufficiently serious to warrant the dispatch of an Imperial commissionner with troops to restore order and negotiate a compromise and a new city constitution between the warring parties.[16]

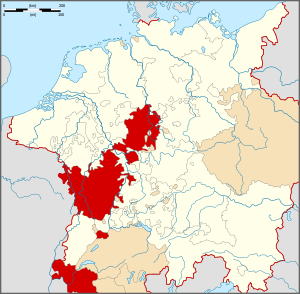

The number of Imperial Cities shrank over time until the Peace of Westphalia. There were more in areas that were very fragmented politically, such as Swabia and Franconia in the southwest, than in the North and the East where the larger and more powerful territories, such as Brandenburg and Saxony, were located, which were more prone to absorb smaller, weaker states.

In the 16th and 17th century, a number of Imperial Cities were separated from the Empire due to external territorial change.[1] Henry II of France seized the Imperial Cities connected to the Three Bishoprics of Metz, Verdun and Toul. Similarly, Louis XIV seized many cities based on claims produced by his Chambers of Reunion. That way, Strasbourg and the ten cities of the Décapole were annexed. Also, when the Old Swiss Confederacy gained its formal independence from the Empire in 1648 (it had been de facto independent since 1499), the independence of the Imperial Cities of Basel, Bern, Lucerne, St. Gallen, Schaffhausen, Solothurn, and Zürich was formally recognized.

With the rise of Revolutionary France in Europe, this trend accelerated enormously. After 1795, the areas west of the Rhine were annexed to France by the revolutionary armies, suppressing the independence of Imperial Cities as diverse as Cologne, Aachen, Speyer and Worms. Then, the Napoleonic Wars led to the reorganization of the Empire in 1803 (see German Mediatisation), where all of the free cities but six — Hamburg, Bremen, Lübeck, Frankfurt, Augsburg, and Nuremberg — lost their independence and were absorbed into neighboring territories. Finally, under pressure from Napoleon, the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806. By 1811, all of the Imperial Cities had lost their independence — Augsburg and Nuremberg had been annexed by Bavaria, Frankfurt had become the center of the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt, a Napoleonic puppet state, and the three Hanseatic cities had been directly annexed by France as part of its effort to enforce the Continental Blockade against Britain. Hamburg and Lübeck with surrounding territories formed the département of Bouches-de-l'Elbe, and Bremen the Bouches-du-Weser.

When the German Confederation was established by the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Hamburg, Lübeck, Bremen, and Frankfurt were once again made Free Cities,[1] this time enjoying total sovereignty as all the members of the loose Confederation. Frankfurt was annexed by Prussia in consequence of the part it took in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866.[1] The three other Free Cities became constituent states of the new German Empire in 1871 and consequently were no longer fully sovereign as they lost control over defence, foreign affairs and a few other fields. They retained that status in the Weimar Republic and into the Third Reich, although under Hitler it became purely notional. Due to Hitler's distaste for Lübeck[17] and its liberal tradition, the need was devised to compensate Prussia for territorial losses under the Greater Hamburg Act, and Lübeck was annexed to Prussia in 1937. In the Federal Republic of Germany which was established after the war, Bremen and Hamburg became constituent states, a status which they retain to the present day. Berlin, which had never been a Free City in its history, also received the status of a state after the war due to its special position in divided post-war Germany.

Regensburg was, apart from hosting the Imperial Diet, a most peculiar city: an officially Lutheran city that nevertheless was the seat of the Catholic prince-bishopric of Regensburg, its prince-bishop and cathedral chapter. The Imperial City also housed three Imperial abbeys: St. Emmeram, Niedermünster and Obermünster. They were five immediate entities fully independent of each other existing in the same small city.

Image gallery

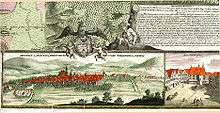

Regensburg

Regensburg Rothenburg in 1572

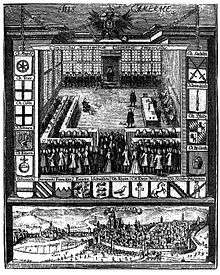

Rothenburg in 1572 Lubeca urbs imperialis libera – Free Imperial City of Lübeck

Lubeca urbs imperialis libera – Free Imperial City of Lübeck

See also

- Free city (antiquity)

- Imperial immediacy

- List of Free Imperial Cities

- Lübeck law

- Royal free city

Notes

- This figure does not include the ten cities of the Décapole, which, while still formally independent from 1648 to 1679, had been placed under the heavy-handed "protection" of the French king.

- "Territorial city" is a term used by modern historians to denote any German city or town that was not a Free Imperial City.

- Examples of such cities were Lemgo (county of Lippe), Gütersloh (county of Bentheim) and Emden (county of East Frisia).

- All the cities of Southern Germany (located in the Swabian, Franconian and Bavarian circles) belonged to the Swabian bench, while all the others belonged to Rhenish bench, even cities such as Lübeck and Hamburg that were quite far from the Rhineland.

Citations

- Holland, Arthur William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 342.

- Whaley, vol.1, p. 26.

- John G. Gagliardo, Germany under the Old Regime, 1600–1790, Longman, London and New York, 1991, p. 4.

- Gagliardo, p. 5

- Joachim Whaley, Germany and the Holy Roman Empire, Oxford University Press, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 250, 510, 532.

- Gagliardo, pp 6–7.

- The Reichsmatrikel contained errors. Some of the 85 cities listed were not free imperial cities (for instance Lemgo) while some cities were omitted (Bremen). Among cities on the list, Metz, Toul, Verdun, Besançon, Cambrai, Strasburg, and the 10 cities of the Alsatian Dekapolis were to be absorbed by France, while Basel, Schaffhausen and St. Gallen would join the Swiss Confederacy.

- G. Benecke, Society and Politics in Germany, 1500–1750, Routledge & Kegan Paul and University of Toronto Press, London, Toronto and Buffalo, 1974, Appendix II.

- G. Benecke, Society and Politics in Germany, 1500–1750, Routledge & Kegan Paul and University of Toronto Press, London, Toronto and Buffalo, 1974, Appendix III.

- Whaley, vol. 1, pp. 532–533.

- Peter H. Wilson, The Holy Roman Empire, 1495–1806, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999, p. 66

- Whaley, vol. 2, p. 210.

- Whaley, vol. 2, p. 211.

- G. Benecke, p. 162.

- Franck Lafage, Les comtes Schönborn, 1642–1756, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2008, vol. II, p. 319.

- Franck Lafage, p. 319–323

- Lubeck, Europe à la Carte

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "article name needed". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.