Political systems of Imperial China

The political systems of Imperial China can be divided into a central political system, a local political system, and a system for the selection of officials. There were three major tendencies in the history of the Chinese political system: the escalation of centralisation, the escalation of absolute monarchy, and the standardisation of the selection of officials.[1] Moreover, there are the ancient supervision system and the political systems created by ethnic minorities, as well as other critical political systems which may be mentioned.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | ||||||||

| Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BCE | ||||||||

| Xia c. 2070 – c. 1600 BCE | ||||||||

| Shang c. 1600 – c. 1046 BCE | ||||||||

| Zhou c. 1046 – 256 BCE | ||||||||

| Western Zhou | ||||||||

| Eastern Zhou | ||||||||

| Spring and Autumn | ||||||||

| Warring States | ||||||||

| IMPERIAL | ||||||||

| Qin 221–207 BCE | ||||||||

| Han 202 BCE – 220 CE | ||||||||

| Western Han | ||||||||

| Xin | ||||||||

| Eastern Han | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 | ||||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | ||||||||

| Jin 266–420 | ||||||||

| Western Jin | ||||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | |||||||

| Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | ||||||||

| Sui 581–618 | ||||||||

| Tang 618–907 | ||||||||

| (Wu Zhou 690–705) | ||||||||

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–979 |

Liao 916–1125 | |||||||

| Song 960–1279 | ||||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | |||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | Western Liao | ||||||

| Yuan 1271–1368 | ||||||||

| Ming 1368–1644 | ||||||||

| Qing 1636–1912 | ||||||||

| MODERN | ||||||||

| Republic of China on mainland 1912–1949 | ||||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present | ||||||||

| Republic of China on Taiwan 1949–present | ||||||||

Fundamental system: Centralised monarchy

Rudiment and establishment

During the Warring States period, Han Feizi proposed the establishment of centralised autocratic monarchy.[2] During the same period, Shang Yang from the state of Qin carried out political reforms in practice.[3] The imperial system was established by the time of Qin, as well as the system of three lords and nine ministers, and the system of prefectures and counties. Weights, measures, currency, and writing were unified. Books and scholars were burned and buried as the ideological control strengthened. Officials were to act as teachers of the law.[4]

Consolidation and reinforcement

To solve the problem of the kingdom, West Han carried out the system of historical assassination, promulgated the decree of mercy and the law of supplementary benefits, executed dethrone 100 schools of thought, while only respecting Confucianism.[5] By implementing the system of three provinces and six ministries, the feudal bureaucracy formed a complete and rigorous system, which weakened the prime minister's power and strengthened the imperial power. The establishment and improvement of the imperial civil examination expanded the source of young government officials. Centralised military power: which removed the military power of senior generals and local commanders in the central government, set up three government officials to command the imperial army and check each other with the privy council.[6] Centralised executive power: the political, military and financial powers of the chief ministers, the privy councillors and the three secretaries divided the prime minister's power. Centralised financial power: by setting up transshipment in each level to manage local finance. Centralised judicial power: by the central government sending civilian officials to serve as local judicial officials. Through the above measures, the emperor mastered the military, administrative, financial, and judicial powers from the central government to the local government, thus eradicated the foundation of feudal vassal separation.[7]

Further development and final shape

In the central government, the executive system of central officials was improved during Yuan dynasty. It established the Xuanzheng Yuan (the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs) to direct religious affairs and to govern the region of Tibet. At the local level, the provincial system was practiced.[8] At the beginning of the Ming dynasty, the prime minister was abolished, and the power was divided into six departments. The local government implemented the division of power among the three functioning departments. The Qing dynasty followed the system of the Ming dynasty, set up more military offices, put up literary prisons, thus strengthened the centralisation of authoritarianism.[9]

Central political systems

Three Lords and Nine Ministers system

The three lords and nine ministers system was a central administrative system adopted in ancient China that was officially instituted in Qin dynasty and later developed in Han dynasty.[10]

Three Lords referred to three highest rank officials in the imperial government, namely:[12]

- the Chancellor

- the Imperial Secretary

- the Grand Commandant

Nine Ministers comprised all the ministers of importance in the central government. They were:[12]

- the Minister of Ceremonies

- the Supervisor of Attendants

- the Commandant of Guards

- the Minister of Coachmen

- the Commandant of Justice

- the Grand Herald

- the Director of the Imperial Clan

- the Grand Minister of Agriculture

- the Small Treasurer

Three departments and six ministries system

The three lords and nine ministers system was replaced by the system of three provinces and six ministries by Emperor Wen of the Sui dynasty.[13] The three departments were Shangshu, Zhongshu and Menxia. The central committee was responsible for drafting and issuing imperial edicts; Subordinate provinces shall be responsible for the examination and verification of administrative decrees; Shangshu was responsible for carrying out important state decrees, and the heads of the three provinces were all prime ministers. The six ministries were officials, households, rites, soldiers, punishments, and workers. The three provinces and six ministries had both divisions of labor and cooperation, and they supervised and contained each other, thus forming a strict and complete system of the feudal bureaucracy, effectively improving administrative efficiency and strengthening the ruling power of the central government. The separation of the three powers weakens the power of the prime minister and strengthens the imperial power. The officially adopted systems of Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties all changed a little on this basis.[14]

| Emperor (皇帝, huángdì) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellery (t 門下省, s 门下省, Ménxiàshěng) | Department of State Affairs (t 尚書省, s 尚书省, Shàngshūshěng) | Secretariat (t 中書省, s 中书省, Zhōngshūshěng) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ministry of Personnel (吏部, Lìbù) | Ministry of Revenue (t 戶部, s 户部, Hùbù) | Ministry of Rites (t 禮部, s 礼部, Lǐbù) | Ministry of War (兵部, Bīngbù) | Ministry of Justice (刑部, Xíngbù) | Ministry of Works (工部, Gōngbù) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prime minister system

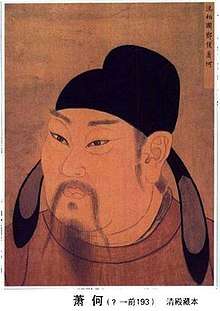

Qin established the system of three lords and nine ministers in the central government. Emperor Wu of the Western Han dynasty reformed the official system implemented the internal and external dynasties system and weakened the power of the prime minister. Emperor Guangwu of the Eastern Han dynasty expanded the power of the Shangshu department. Sui and Tang dynasties established the system of three provinces and six departments, dividing the power of the prime minister into three and containing each other, which reflected the strengthening of the imperial power. In the northern song dynasty, under the chancellors, the chief ministers were appointed as deputy ministers to divide the administrative power of the chancellors. There were privy secretaries to divide the military power and three divisions to divide the financial power.[15] The Yuan dynasty set up a Zhongshu province, with prime ministers on the right and left, exercising the functions and powers of prime ministers. The Ming dynasty abolished the prime minister and divided the power into six parts. Yongle dynasty set up a cabinet and implemented "draft vote." The military offices were set up in the Qing dynasty, and the remnants of the prime minister system disappeared, reflecting that the imperial power had reached its peak. From the changes, we can see that the emperor divided and weakened the power of the prime minister, gradually concentrated all kinds of power in his own hands, and thus effectively implemented the autocratic monarchy. Notable prime ministers include Prime Minister Zhu of Shu, Prime Minister Xiao of Western Han and Prime Minister Wang of Song.[16][17]

Local political systems

Enfeoffment system

To consolidate the power of slave owners, the rulers of the Western Zhou dynasty implemented the system of enfeoff vassals politically, which enabled the Zhou dynasty to consolidate its rule and expand its territory.[18] In the spring and autumn period, it gradually collapsed and was replaced by the system of prefectures and counties, which remained in some later dynasties.[19]

Prefecture and county system

During the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period, the Qin dynasty was carried out nationwide, thus replacing the feudal system nationwide, greatly weakening the independence of local authorities and strengthening the centralization of power. This was an epoch-making reform in China's local administrative system. The prefecture and county system was used for a long time in ancient China, with a very far-reaching influence.[20]

Province system

At the beginning of the Western Han dynasty, the system of prefectures and counties was implemented in local areas, and at the same time, the system of enfeoffment was established. Counties and countries were parallel to each other, which was not conducive to the unified management of the country, with the risk of division. The Yuan dynasty was a feudal country with a vast territory at that time. Its establishment consolidated the unification of the country and ensured the centralization of power in the system. The provincial system of the Yuan dynasty had a far-reaching influence on the political system of later generations. Since then, the provincial system has become the local administrative organ of China, which was followed in the Ming and Qing dynasties and has been retained until today.[21]

| Administrative unit | Administrator title | Appointment | Authority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Province (州 zhou) | Governor (牧 mu) | Central | Executive |

| Inspector (刺史 cishi) | Central | No direct authority | |

| Commandery (郡 jun) | Grand administrator (太守 taishou) | Central | Executive |

| Kingdom (王國 wangguo) | Chancellor (相 xiang) | Central | Executive |

| King (王 wang) | Hereditary | No real authority | |

| County (縣 xian) | Prefect (令 ling) Chief (長 zhang) | Central | Executive |

Monk system

In the Ming dynasty, Tibet practiced the system of monks and officials. Because the Tibetan people believed in Tibetan Buddhism, the Ming government used religion to rule the Tibetan people which was later called the 'monk system'.[22]

Eight banners system

The eight banners system was in the late Ming dynasty when Nuzhen rulers Nurhaci to create a system of eight banners system according to the military organization form the Jurchen establishment, controlled by the aristocrat, with military conquering three functions, administrative management, organize production, is a soldier and unity of social organization, is a military organization and administrative management system, promote the development of the Nuzhen society. The eight banners army played an important role in unifying China in the Qing dynasty.[23] However, with the invasion of western capitalism , the corruption of the eight banners army itself and the gradual decline of its combat effectiveness, the Hunan army and Huai army, which rose up in the process of suppressing the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, had a great impact on it.[24]

Bureaucratisation of native officers

The Ming dynasty followed the rule of the Yuan dynasty in the southwest minority areas, where the chieftain system was implemented. These chieftain officials held by local minorities had autonomy over the administration of the areas under their jurisdiction, and they could be hereditary and had great power, which gradually evolved into a separatist force.[25]

Official selection system

Evolution of the system of selecting officials

The selection of official standards by family background gradually developed to the selection of talent, while the selection method by selection gradually developed to the form of public examination. The selecting mechanism based on talent later became institutionalised and much more rigorous.[27]

| Degree | Ranks | Exam | Times held |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child student (Tongsheng) | County/Prefectural | Annual (February/April) | |

| Student member (Shengyuan) | Granary student (1st class) Expanded student (2nd class) Attached student (3rd class) | College | Triennial (twice) |

| Recommended man (Juren) | Top escorted examinee (1st rank) | Provincial | Triennial |

| Tribute scholar (Gongshi) | Top conference examinee (1st rank) | Metropolitan | Triennial |

| Advanced scholar (Jinshi) | Top thesis author (1st rank) Eyes positioned alongside (2nd rank) Flower snatcher (3rd rank) | Palace | Triennial |

Imperial supervision systems

Qin dynasty

The central government set up the imperial historian, whereas the local government set up the imperial supervisor.[28]

Western Han dynasty

Emperor Wudi of the Han dynasty set 13 prefectures as the supervision area, and set the provincial history department for supervision.[18]

Eastern Han dynasty

The supervision power of the provincial governor was further strengthened, and the local administrative power and military power were gradually increased. At the end of the Eastern Han dynasty, the provincial governor evolved into the local highest military and political officer.[29]

Northern Song dynasty

There was a general court to supervise the prefectures, which could report directly to the emperor.[28]

Ming dynasty

The local government set up the department of criminal investigation to administer local supervision and justice. In addition, the factory also set up a spying agency to monitor officials and civilians at all levels.[30]

Political systems created by ethnic minorities

Uniform land system, rent modulation, government military system, Fan-Han divide and rule system, fierce peace and restraint, provincial system, eight flag system are critical systems created by ethnic minorities to be mentioned in the history.[31]

Other critical political systems in ancient China

Abdication system

At the end of primitive society, the democratic election of tribal alliance leaders was carried out within the circle of the noble families. It is not only the reflection of primitive public ownership in politics, but also the signal of primitive society collapse.[32]

Hereditary system

A hereditary system with its distinctive privatization embodied the significant progress of society.[33]

Patriarchal system

Since the Western Zhou dynasty, the patriarchal clan system was a system in which the inheritance relationship and the title were determined by blood relationship and marital status. The patriarchal clan system and privilege system formed by the patriarchal system had a far-reaching influence on later generations.[34]

Gentry system

The gentry was developed from the powerful landlords and belonged to the privileged stratum of the landlord class. The gentry system was formed in the Wei and Jin dynasties. It was a system plagued by corruption that selected officials according to the level of their family backgrounds.[35]

References

- The Cambridge history of ancient China : from the origins of civilization to 221 B.C. Loewe, Michael., Shaughnessy, Edward L., 1952-. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 1999. ISBN 0521470307. OCLC 37361770.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Dao companion to the philosophy of Han Fei. Goldin, Paul Rakita, 1972-. Dordrecht: Springer. 2013. ISBN 9789400743182. OCLC 811051672.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Shang, Yang, -338 B.C.; 商鞅, -338 B.C. (1993). Shang jun shu quan yi. Zhang, Jue., 张觉. (Di 1 ban ed.). Guiyang: Guizhou ren min chu ban she. ISBN 7221029148. OCLC 45812779.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sima, Qian, approximately 145 B.C.-approximately 86 B.C. (1993). Records of the Grand Historian. Qin dynasty. Watson, Burton, 1925-2017. Hong Kong: Research Centre for Translation, Chinese University of Hong Kong. ISBN 0231081693. OCLC 28322132.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Skocpol, Theda. (1979). States and social revolutions : a comparative analysis of France, Russia, and China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052122439X. OCLC 4135856.

- Qiu, Xigui; 裘錫圭. (2000). Chinese writing. Mattos, Gilbert Louis, 1939-, Norman, Jerry, 1936-2012,, Qiu, Xigui,, 裘錫圭. Berkeley, California. ISBN 1557290717. OCLC 43936866.

- Sommer, Matthew Harvey, 1961- (2015-09-15). Polyandry and wife-selling in Qing Dynasty China : survival strategies and judicial interventions. Oakland, California. ISBN 9780520962194. OCLC 913086388.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Bellezza, John Vincent. The dawn of Tibet : the ancient civilization on the roof of the world. Lanham, MD. ISBN 9781442234611. OCLC 870098261.

- Zhongguo Qing dai zheng zhi shi. Xu, Kai., 徐凯. (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Ren min chu ban she. 1994. ISBN 7010017573. OCLC 32676386.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Zhou, Haiwen (April 2012). "Internal Rebellions and External Threats: A Model of Government Organizational Forms in Ancient China" (PDF). Southern Economic Journal. 78 (4): 1120–1141. doi:10.4284/0038-4038-78.4.1120. ISSN 0038-4038.

- Ch'ü (1972), 68–69.

- Li, Konghuai (李孔懷) (2007). Zhongguo gu dai xing zheng zhi du shi (Xianggang di 1 ban ed.). Xianggang: San lian shu dian (Xianggang) you xian gong si. ISBN 9789620426544. OCLC 166413670.

- Higham, Charles (2004). Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations. New York, NY: Facts On File. ISBN 0816046409. OCLC 51978070.

- Lü, Simian (吕思勉) (2008). Zhongguo tong shi : cha tu zhen cang ben = the history of China (1st ed.). Beijing: New World Press. ISBN 9787802285699. OCLC 232550968.

- Zeng, Jifen, 1852-1942. (1993). Testimony of a Confucian woman: the autobiography of Mrs. Nie Zeng Jifen, 1852-1942. Kennedy, Thomas L., 1930-2015., Kennedy, Micki. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0820315095. OCLC 26129546.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cotterell, Arthur. (2006). Leadership lessons from the ancient world : how learning from the past can win you the future. Lowe, Roger, 1954-, Shaw, Ian, 1944-. Chichester, England: John Wiley. ISBN 9781119208457. OCLC 70863722.

- Yuan, Naiying.; 袁乃瑛. (2004). Selections from classical Chinese historical texts : glossaries, analyses, exercises. Tang, Hai-tao., Geiss, James., Sima, Qian, approximately 145 B.C.-approximately 86 B.C., Ban, Gu, 32-92., Fan, Ye, 398-445., Chen, Shou, 233-297. Princeton, N.J. ISBN 0691118345. OCLC 57523905.

- The Cambridge history of China. Twitchett, Denis Crispin, 1925-2006., Fairbank, John King, 1907-1991. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. 1996. ISBN 9780521243278. OCLC 2424772.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Janecek, P.; Vorburger, J.; Campana, A.; Stamm, O. (1975). "[Continuous subcutaneous pH monitoring in newborns with abnormal metabolism (author's transl)]". Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde. 35 (7): 511–517. ISSN 0016-5751. PMID 2513.

- Xuan, Xu (2013). "Introduction". Social Sciences in China. 34 (1): 122–123. doi:10.1080/02529203.2013.760720. ISSN 0252-9203.

- Yu-ch'uan, Wang (1949). "An Outline of The Central Government of The Former Han Dynasty". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 12 (1/2): 134–187. doi:10.2307/2718206. JSTOR 2718206.

- Xie, Chongguang.; 谢重光. (2009). Zhong gu fo jiao seng guan zhi du he she hui sheng huo (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Shang wu yin shu guan. ISBN 9787100059084. OCLC 433512892.

- Gyllenbok, Jan, 1963- (2018-04-12). Encyclopaedia of historical metrology, weights, and measures. Volume 3. Cham. ISBN 9783319667126. OCLC 1031847554.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Conflicting counsels to confuse the age : a documentary study of political economy in Qing China, 1644-1840". sydney.primo.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- "Mongolian rule in China : local administration in the Yuan Dynasty". sydney.primo.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- Liu, Haifeng (2006). "Rehabilitation of the imperial examination system". Frontiers of Education in China. 1 (2): 300–315. doi:10.1007/s11516-006-0009-0. ISSN 1673-341X.

- "宋元科舉三錄 / 徐乃昌校栞.; Song Yuan ke ju san lu". sydney.primo.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- Zhongguo gu dai jian cha zhi du fa zhan shi. JIa, Yuying., 贾玉英. (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Ren min chu ban she. 2004. ISBN 7010042411. OCLC 57198607.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Roberts, J. M. (John Morris), 1928-2003. (1997). A short history of the world. New York. ISBN 019511504X. OCLC 35990297.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Su, Li, 1955- (2018-08-07). The constitution of ancient China. Zhang, Yongle,, Bell, Daniel (Daniel A.), 1964-, Ryden, Edmund. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 9781400889778. OCLC 1037945918.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pines, Yuri. (2012). The everlasting empire : the political culture of ancient China and its imperial legacy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400842278. OCLC 782923553.

- The Ch'in and Han empires, 221 B.C. - A.D. 220. Twitchett, Denis Crispin, 1925-2006,, Loewe, Michael. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. 1986. ISBN 9781139054737. OCLC 317592775.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Emperor and ancestor : state and lineage in South China". sydney.primo.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- Zhang, Qizhi (2015-04-15). An introduction to Chinese history and culture. Heidelberg. ISBN 9783662464823. OCLC 907676443.

- Tackett, Nicolas (2014). The destruction of the medieval Chinese aristocracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Asia Center.