Goguryeo–Tang War

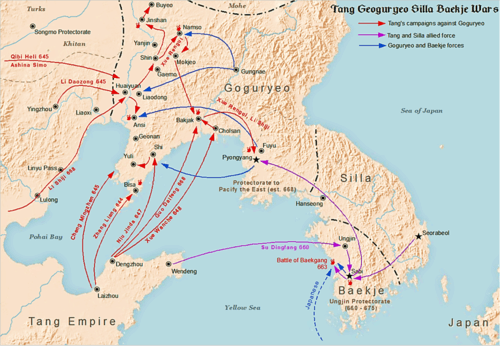

The Goguryeo–Tang War[1] occurred from 645 to 668 and was fought between the Goguryeo Kingdom and Tang Dynasty. During the course of the war, the two sides allied with various other states. Goguryeo successfully repulsed the invading Tang armies during the first Tang invasions of 645-648. After conquering Baekje in 660, Tang and Silla armies invaded Goguryeo from the north and south in 661, but were forced to withdraw in 662. In 666, Yeon Gaesomun died and Goguryeo became plagued by violent dissension, numerous defections, and widespread demoralization.[3] The Tang–Silla alliance mounted a fresh invasion in the following year, aided by the defector Yeon Namsaeng.[4] In late 668, exhausted from numerous military attacks and suffering from internal political chaos, the kingdom of Goguryeo and the remnants of Baekje army succumbed to the numerically superior armies of the Tang Dynasty and Silla.

| Goguryeo–Tang War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Tang Silla |

Goguryeo Baekje Yamato Mohe | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Tang: Queen Seondeok (645-647) Queen Jindeok (647-654) King Muyeol (654-661) King Munmu (661-668) |

Goguryeo: Baekje: Emperor Tenji Empress Saimei | ||||||

The war marked the end of the Three Kingdoms of Korea period which had lasted since 57 BCE. It also triggered the Silla–Tang War during which the Silla Kingdom and the Tang Empire fought over the spoils they had gained.

Onset

The Silla Kingdom had made numerous requests to the Tang court for military assistance against Goguryeo, which the Tang court began to consider not long after they had decisively defeated the Göktürks in 628.[5] At the same time, however, Silla was also engaged in open hostilities with Baekje in 642.[5] A year before in 641, King Uija had assumed the throne of Baekje.[6] In 642, King Uija attacked Silla and captured around 40 strongpoints.[7] Meanwhile, in 642, the military dictator Yeon Gaesomun murdered over 180 Goguryeo aristocrats and seized the Goguryeo throne.[6] He placed a puppet king onto the throne after killing the king in 642.[8] These newly formed governments in Baekje and Goguryeo were preparing for war and had established a mutual alliance against Tang and Silla.[6]

Course of the war

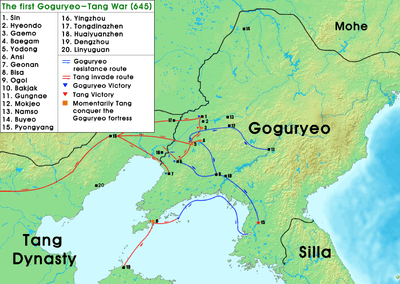

Conflict in 645

Emperor Taizong of Tang used Yeon Gaesomun's murder of the Goguryeo king as the pretext for his campaign and started preparations for an invasion force in 644.[8] General Li Shiji commanded an army of 60,000 Tang soldiers and an undisclosed number of tribal forces[8] which gathered at Youzhou.[8] Emperor Taizong commanded an armored cavalry of 10,000 strong.[8] His cavalry eventually met up and joined General Li Shiji's army during the expedition.[8] A fleet of 500 ships also transported an additional 40,000 conscripted soldiers and 3,000 military gentlemen (volunteers from the elite of Chang'an and Luoyang).[8] This fleet sailed from the Liaodong Peninsula to the Korean Peninsula.[8]

In April 645, General Li Shiji's army departed from Yincheng (present-day Chaoyang).[9] On 1 May, they crossed the Liao River into Goguryeo territory.[9] On 16 May, they laid siege to Gaimou (Kaemo), which fell after only 11 days, capturing 20,000 people and confiscating 100,000 shi (6 million liter) of grain.[9]

Afterwards, General Li Shiji's army advanced to Liaodong (Ryotong).[9] On 7 June, they crushed a Goguryeo army of 40,000 troops strong, which had been sent to the city to relieve the city from the Tang siege.[9] A few days later, Emperor Taizong's cavalry arrived at Liaodong.[9] On 16 June, the Tang army successfully set Liaodong ablaze with incendiary projectiles and breached its defensive walls,[9] resulting in the fall of Liaodong to the Tang forces.[9][10]

The Tang army marched further to Baiyan (Paekam) and arrived there on 27 June.[9] However, the Goguryeo commanders surrendered the city to the Tang army.[9] Afterwards, Emperor Taizong ordered that the city must not be looted and its citizens must not be enslaved.[9]

On 18 July, the Tang army arrived at Ansi Fortress.[9] A Goguryeo army, including Mohe troops, were sent to relieve the city.[9] The reinforcing Goguryeo army totaled 150,000 troops.[11] However, Emperor Taizong sent General Li Shiji with 15,000 troops to lure the Goguryeo forces.[9] Meanwhile, another Tang force would secretly flank the enemy troops from behind.[9] On 20 July, the two sides met at the Battle of Jupilsan and the Tang army came out victorious.[9] Most of the Goguryeo troops dispersed after their defeat.[11] The remaining Goguryeo troops fled to a nearby hill, but they surrendered the next day after a Tang encirclement.[9] The Tang forces took 36,800 troops captive.[9] Of these prisoners, the Tang forces sent 3500 officers and chieftains to China, executed 3300 Mohe troops, and eventually released the rest of the ordinary Goguryeo soldiers.[9] However, the Tang army could not breach into the city of Ansi,[5][10][12] which was defended by the forces of Yang Manchun.[5][10] Tang troops attacked the fortress as many as six or seven times per day, but the defenders repulsed them each time.[13] As days and weeks passed, Emperor Taizong considered abandoning the siege of Ansi to advance deeper into Goguryeo, but Ansi was deemed to pose too great of a threat to abandon during the expedition.[12] Eventually, Tang staked everything on the construction of a huge mound, but it was captured and successfully held by the defenders despite three days of frantic assaults by Tang troops.[14] Furthermore, exacerbated by worsened conditions for the Tang army due to cold weather (winter was approaching) and diminishing provisions, Emperor Taizong was compelled to order a withdrawal from Goguryeo on October 13,[14] but left behind an extravagant gift for the commander of Ansi Fortress.[10] Tang Taizong's retreat was difficult and many of his soldiers died.[14]

Taizong himself tended to the injuries of the Tujue Generals Qibi Heli and Ashina Simo, who were both wounded during the campaign against Goguryeo.[15]

Conflicts in 654–668 and fall of Goguryeo

Under Emperor Gaozong's reign, the Tang Empire formed a military alliance with the Silla Kingdom.[16] When Goguryeo and Baekje attacked Silla from the north and west respectively, Queen Seondeok of Silla sent an emissary to the Tang empire to desperately request military assistance.[16] In 650, Emperor Gaozong received a poem, written by Queen Jindeok of Silla, from the princely emissary Kim Chunchu, who would later accede the Silla throne as King Muyeol.[5] In 653, Baekje allied with Yamato Wa.[17] Even though Baekje was allied with Goguryeo, the Han River valley separated the two states and was a hindrance in coming to each other's aid in time of war.[17] King Muyeol assumed the Silla throne in 654.[18] Between 655 and 659, the border of Silla was harassed by Baekje and Goguryeo; Silla therefore requested assistance from Tang.[19] In 658, Emperor Gaozong sent an army to attack Goguryeo[20] but was unable to overcome Goguryeo's stalwart defenses.[21] King Muyeol suggested to Tang that the Tang–Silla alliance first conquer Baekje, breaking up the Goguryeo–Baekje alliance, and then attack Goguryeo.[21]

In 660, the Tang empire and the Silla kingdom sent their allied armies to conquer Baekje.[20] The Baekje capital Sabi fell to the forces of Tang and Silla.[22][23] Baekje was conquered on 18 July 660,[16] when King Uija of Baekje surrendered at Ungjin.[5] The Tang army took the king, the crown prince, 93 officials, and 20,000 troops as prisoners.[23] The king and the crown prince were sent as hostages to the Tang empire.[16] The Tang empire annexed the territory and established five military administrations to control the region instead of Silla, which they painfully accepted.[24] In a final effort, General Gwisil Boksin led the resistance against Tang occupation of Baekje.[25] He requested military assistance from their Yamato allies.[25] The Tang fleet, comprising 170 ships, advanced towards Chuyu and encircled the city at the Baekgang River.[26] As the Yamato fleet engaged the Tang fleet, they were attacked by the Tang fleet and were destroyed.[26] In 663, the Baekje resistance and Yamato forces were annihilated by the Tang and Silla forces at the Battle of Baekgang.[27] Subsequently, Prince Buyeo Pung of Baekje and his remaining men fled to Goguryeo.[26]

After the conquest of Baekje in 660, the Tang and Silla forces planned to invade Goguryeo.[22] In 661, the Tang forces set off to Goguryeo.[28] As the Tang army advanced with 350,000 troops,[29] Silla was only requested to provide supplies during this expedition.[29] In 662, Yeon Gaesomun defeated General Pang Xiaotai at the Battle of Sasu.[30][31] The Tang army besieged Pyongyang, Goguryeo's capital, for several months until February 662, when it had to withdraw from the campaign due to the harsh winter conditions[28] and the defeat of its subsidiary force.[32]

In 666, the Goguryeo dictator Yeon Gaesomun died and an internal struggle between his sons for power broke out.[29] Goguryeo was thrown into chaos and weakened by the succession struggle among his sons and younger brother, with his eldest son (and successor) defecting to Tang and his younger brother defecting to Silla.[4][33] Yeon Gaesomun's death paved the way for a fresh invasion by Tang and Silla in 667, this time aided by Yeon Gaesomun's oldest son.[4] The violent dissension resulting from Yeon Gaesomun's death proved to be the primary reason for the Tang–Silla triumph, thanks to the division, defections, and widespread demoralization it caused.[3] The alliance with Silla also proved to be invaluable, thanks to the ability to attack Goguryeo from opposite directions, and both military and logistical aid from Silla.[3] In 668, the Tang and Silla forces besieged and conquered Pyongyang, which led to the conquest of Goguryeo.[5][22][29] Over 200,000 prisoners were taken by the Tang forces and sent to Chang'an.[34]

Aftermath

In 669, the Tang government established the Protectorate General to Pacify the East to control the former territories of Goguryeo.[29] A subordinate office was placed in Baekje.[29] By the end of the war, the Tang empire had taken control over the former territories of Baekje and Goguryeo and tried to assert dominion over Silla.[35] Large parts of the Korean Peninsula were occupied by the Tang forces for about a decade.[28]

However, the Tang occupation of the Korean Peninsula proved to be logistically difficult due to shortage of supplies which Silla had provided previously.[36] Furthermore, Emperor Gaozong was ailing, so Empress Wu took a pacifist policy, and the Tang empire was diverting resources towards other priorities.[37] This situation favored Silla, because soon Silla would have to forcibly resist the imposition of Chinese rule over the entire peninsula.[37] War was imminent between Silla and Tang.[35][37]

References

- Shin, Michael D., ed. (2014). Korean History in Maps: From Prehistory to the Twenty-first Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-107-09846-6.

The Goguryeo-Tang War | 645-668

- Miller, Owen (Dec 15, 2014). Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. p. 30. Retrieved August 7, 2015. "Goguryeo surrenders to the allied armies of Silla and Tang forces. Fall of Goguryeo."

- Graff, David. Medieval Chinese Warfare 300-900. Routledge. p. 200. ISBN 9781134553532. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Yi, Ki-baek. A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780674615762. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Seth 2010, 44.

- Farris 1985, 8.

- Whiting, Marvin C. Imperial Chinese Military History: 8000 BC-1912 AD. iUniverse. p. 257. ISBN 9780595221349. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- Graff 2002, 196.

- Graff 2002, 197.

- Lee 1997, 16

- Joe 1972, 16.

- Graff 2002, 197–198

- Yi, Ki-baek. A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780674615762. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- Graff, David. Medieval Chinese Warfare 300-900. Routledge. p. 198. ISBN 9781134553532. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Skaff 2012, p. 95.

- Lee 1997, 17

- Kim 2005, 37.

- Kim 2005, 37–38.

- Kim 2005, 38.

- Ebrey, Walthall & Palais 2006, 106.

- Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul. Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 486. ISBN 9781136639791. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- Yu 2012, 31.

- Kim 2005, 39

- Ebrey, Walthall & Palais 2006, 106–107.

- Farris 1985, 10.

- Farris 1985, 11.

- Ota 2012, 302.

- Lee 1997, 18.

- Kim 2005, 40.

- 옆으로 읽는 동아시아 삼국지 1 (in Korean). EASTASIA. ISBN 9788962620726. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "통일기". 한국콘텐츠진흥원. Korea Creative Content Agency. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- Graff, David. Medieval Chinese Warfare 300-900. Routledge. p. 199. ISBN 9781134553532. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Kim, Djun Kil. The History of Korea, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 49. ISBN 9781610695824. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Lewis 2009, 154.

- Fuqua 2007, 40.

- Seth 2010, 45.

- Kim 2005, 41.

Bibliography

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006). East Asia: A cultural, social, and political history. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780618133840.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farris, William Wayne (1985). Population, disease, and land in early Japan, 645-900. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674690059.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fuqua, Jacques L. (2007). Nuclear endgame: The need for engagement with North Korea. Westport: Praeger Security International. ISBN 9780275990749.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Graff, David A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415239554.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joe, Wanne J. (1972). Traditional Korea: A Cultural History. Seoul: Chung'ang University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kim, Djun Kil (2005). The history of Korea (1st ed.). Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313038532.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Kenneth B. (1997). Korea and East Asia: The story of a phoenix. Westport: Praeger. ISBN 9780275958237.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2009). China's cosmopolitan empire: The Tang dynasty. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674033061.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ota, Fumio (2012). "The Japanese way of war". The Oxford handbook on war. Corby: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199562930.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seth, Michael J. (2010). A history of Korea: From antiquity to the present. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742567177.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- West, Barbara A. (2009). Encyclopedia of the peoples of Asia and Oceania. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 9781438119137.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yu, Chai-Shin (2012). The new history of Korean civilization. Bloomington: iUniverse. ISBN 9781462055593.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)