War of the Eight Princes

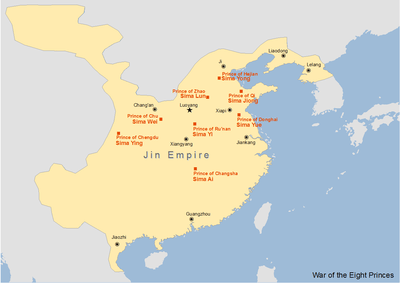

The War of the Eight Princes, Rebellion of the Eight Kings, or Rebellion of the Eight Princes (simplified Chinese: 八王之乱; traditional Chinese: 八王之亂; pinyin: bā wáng zhī luàn; Wade–Giles: pa wang chih luan) was a series of civil wars among kings/princes (Chinese: wáng 王) of the Chinese Jin dynasty from 291 to 306 AD. The key point of contention in these conflicts was the regency over the developmentally disabled Emperor Hui of Jin. The name of the conflict is derived from the biographies of the eight princes collected in Chapter 59 of the Book of Jin (Jinshu).

The "War of the Eight Princes" is somewhat of a misnomer: rather than one continuous conflict, the War of the Eight Princes saw intervals of peace interposed with short and intense periods of internecine conflict. At no point in the whole conflict were all of the eight princes on one side of the fighting (as opposed to, for example, the Rebellion of the Seven States). The literal Chinese translation, Disorder of the Eight Kings, may be more appropriate in this regard.

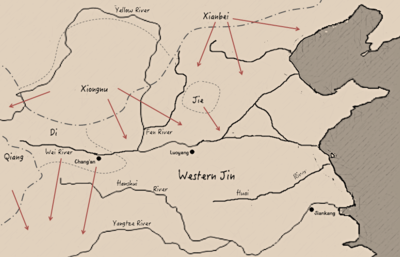

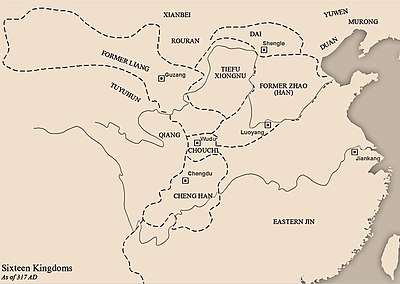

While initial conflicts were relatively minor and confined to the imperial capital of Luoyang and its surroundings, the scope of the war expanded with each new prince who entered the struggle. The numerous tribal groups in the north and northwest who had been heavily drafted into the military then exploited the chaos to seize power.[1] At its conclusion, the war devastated the Jin heartlands in northern China, and ushered in the era of Wu Hu uprisings that ended Western Jin, causing centuries of warfare between northern barbarian kingdoms and southern Chinese dynasties.

The Eight Princes

While many princes participated in the conflict, the eight major players in this conflict were:

| Prince | Title | Lifespan |

|---|---|---|

| Sima Liang | Prince Wencheng of Runan | 233-291 |

| Sima Wei | Prince Yin of Chu | 271-291 |

| Sima Lun | Prince of Zhao | 250-301 |

| Sima Jiong | Prince Wumin of Qi | ?-302 |

| Sima Ai (or Sima Yi) | Prince Li of Changsha | 277-304 |

| Sima Ying | Prince of Chengdu | 279-306 |

| Sima Yong | Prince of Hejian | ?-307 |

| Sima Yue | Prince Xiaoxian of Donghai | ?-311 |

Other people of note included Emperor Hui of Jin, co-regent Yang Jun, Empress Dowager Yang, Empress Jia Nanfeng, and the senior minister Wei Guan.

Family Tree

| The Eight Princes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Background

Sima Yi, an official, general, and regent of the state of Cao Wei during the Three Kingdoms period, effectively seized control of Wei in early 249 after instigating a successful coup against his co-regent, Cao Shuang. Sima Yi and two of his sons, Sima Shi and Sima Zhao, came to serve as the de facto rulers of Wei.

In 266, Sima Zhao's eldest son, Sima Yan, forced the Wei emperor Cao Huan to abdicate the throne and established the Jin dynasty. Sima Yan sought to bolster the power of the Sima clan by enfeoffing his uncles, cousins, and sons. Those with large enfeoffments were entitled to an army of five thousand, those with medium enfeoffments were entitled to an army of three thousand, and those with small enfeoffments were entitled to an army of one thousand five hundred. As time passed, these princes and dukes were given administrative powers over their lands and were granted the power to levy taxes and employ central officials.

Following the death of Sima Yan, posthumously Emperor Wu of Jin, in 290, a complex power struggle known as the War of the Eight Princes erupted among the Sima clan. The new emperor, Emperor Hui of Jin, was developmentally disabled. The emperor's stepmother, Empress Yang Zhi, exerted the most power at court and empowered the Yang consort clan, with her father Yang Jun with authority. The emperor's wife, Empress Jia Nanfeng, was not happy with being excluded from this state of affairs. She enlisted the help of Sima Wei and Sima Liang. Sima Wei's troops entered Luoyang unopposed by the central government. In 291, Empress Jia issued an edict accusing Yang Jun of treason. Yang Jun was killed by Wei's troops, the empress dowager was starved to death under house arrest, and 3000 members of the Yang clan were executed.

Prince of Runan (Sima Liang), 291

After the coup against Empress Yang Zhi, the emperor's grand-uncle, Sima Liang, the Prince of Runan, became regent. Liang threatened Sima Wei and pressured him to return his fief of Jing Province. A few weeks later Empress Jia and Wei, who was at the time in control of a battalion of imperial guards, conspired to have Liang killed. An imperial edict was issued accusing Liang of treason and Wei led another coup killing Liang.[2]

Prince of Chu (Sima Wei), 291

Immediately following the death of Sima Liang, Sima Wei was advised to expand his power at the expense of Empress Jia, but he hesitated to take action against the empress. Two days after Liang's death, Empress Jia spread a rumor around Wei's camp accusing him of having forged the imperial edict that had ordered Liang to be killed. Deserted by his followers, Wei was captured and executed.[2]

Empress Jia ruled the court in the emperor's name until 300. Rumors began to spread of Empress Jia's personal debauchery and tyrannical behavior, laying the seeds of discontent that would surface by the end of the decade.[2][3]

A Di leader Yang Maosou set up the state of Chouchi south of Tianshui in 296.[4]

Empress Jia, 300

In 299, Empress Jia orchestrated the arrest of Sima Yu, heir to the throne, by convincing him while drunk to copy a text that said, amongst other things, that Emperor Hui should abdicate in favor of him. Empress Jia then presented the copied text to Emperor Hui, who then decided to execute his son. Empress Jia desired the punishment to be carried out immediately but Emperor Hui instead merely deposed Sima Yu and kept him under house arrest for the time being.[5]

Sima Lun, Prince of Zhao, was tutor to the prince at the time and considered a member of Empress Jia's inner circle. He also commanded some troops in the capital as general of the Right Army and was known to be "avaricious and false" as well as "simple and stupid," heeding only the advice of Sun Xiu. Lun had long wished to betray the empress, but Sun Xiu convinced him to wait until Yu was out of the way, arguing that because of Lun's reputed loyalty to the empress, Lun's actions would only lead to the accession of Yu, who would then exact revenge on Lun himself. With Lun's encouragement, the empress murdered Yu. Lun then produced an edict allegedly from Emperor Hui, arrested Empress Jia and put her under house arrest, and later forced her to commit suicide by drinking gold powered wine. Lun, again by way of forged imperial edict, first appointed himself as Grand Vizier, and in 301, crowned himself emperor, putting Emperor Hui under house arrest.[6]

Prince of Zhao (Sima Lun), 301

Sima Lun's usurpation of the throne was hotly contested by the other princes. Sima Yun, Prince of Huainan, rebelled against Lun with only 700 men. One of Lun's supporters pretended to defect to Yun, then killed him, ending his rebellion.[6]

Three major princes allied themselves to oppose him: in Xuchang, the Prince of Qi, Sima Jiong; in Chang'an, the Prince of Hejian, Sima Yong, and in Chengdu, the Prince of Chengdu, Sima Ying. Lun had initially sent them away with promotions and officers to spy on them, but this backfired when Jiong used the officer given to him to his advantage. He sent the officer away to suppress a local rebellion and then executed him, immediately rebelling afterwards. Ying and Yong followed in his footsteps. Ying was described as beautiful but dull in the mind and did not read books, but he heeded his advisor Lu Zhi's advice to rally governors to his cause. Some 200,000 troops, including the forces of Sima Ai, Prince of Changsha, were thus assembled near Ye. From Changsha, Yong dispatched troops under Zhang Fang to support Lun.[7]

Lun sent Sun Fu and Zhang Hong with 24,000 men to secure the passes and 30,000 under Sun Hui to confront Ying. Zhang Hong confronted Jiong and defeated him several times before Jiong retreated and made camp at Yingyin, midway between Yangdi and Xuchang. Sun Fu panicked and fled back to Luoyang, spreading rumors that Zhang Hong had been defeated. Lun ordered the main army to return and protect Luoyang and then to confront Ying again. However by this time Jiong had reversed his early defeats and forced Zhang Hong back toward the capital. Sun Hui led the main army against Ying at Yellow Bridge, defeating the prince and killing 10,000. Ying rallied his troops and returned with a counterattack, smashing Hui's forces at the Chou River north of the Yellow River.[8]

On 30 May 301, the general of the Left Guard led troops into the palace and arrested Lun. He spent the next few days denouncing his own conduct before he was executed. Emperor Hui of Jin was reinstated. He celebrated the occasion with a five-day non-stop drinking binge. Ying reached the capital on 1 June and Yong on 7 June. Jiong entered the capital with "several hundred thousand armored soldiers, before whom the capital trembled in awe" on 23 July.[8]

On 11 August 301, Sima Jiong received control of the government and Sima Ai was placed in command of the Left Army. However Sima Ai was discontent with Jiong's rule, who he considered to have usurped authority. On the advice of Lu Zhi, Sima Ying withdrew to Ye to care for his ailing mother. He then arranged for grain to be transported to the famine-stricken region of Yangdi, which had been devastated by war. He had over 8000 coffins constructed for high-ceremony funerals of those who had fallen in battle and over 14,000 of Sima Lun's soldiers to be buried. Jiong ordered Ying to return to the capital, but he refused. These were all Lu Zhi's ideas.[9]

Prince of Qi (Sima Jiong), 302

In mid-302, the last of Sima Yu's lineage died, throwing the line of succession into confusion. Sima Jiong designated the son of the Emperor's younger brother Sima Xia, Sima Tan, as crown prince. At the same time, Sima Yue, Prince of Donghai, was appointed to direct the Central Secretariat.[9]

Jiong wanted to appoint Li Han, one of Sima Yong's chief of staff, to be colonel of the Army of Readiness. Li Han was afraid to accept the appointment due to enmity between himself and Huangfu Shang, one of Jiong's advisers. Li Han fled to Yong claiming to bear a secret imperial decree ordering Yong to eliminate Jiong. Yong rose in rebellion with some 100,000 troops with the aid of Sima Ying. When news of the rebel advance reached the capital, Sima Ai was implicated in a plot to remove Jiong. Jiong sent troops to kill Ai, who fled to the imperial palace for protection. There, using both imperial guards and his own personal forces, Ai defended the palace against Jiong within Luoyang for three days. Eventually Jiong's own officers betrayed him and he was captured and killed.[10]

Sima Ai seized control of the capital but deferred authority to his brother, Ying.[10]

Prince of Changsha (Sima Ai), 303–304

Sima Ai's administration failed to deal with rebel movements in the empire. In the southwest, the Ba-Di rebellion started by Li Te raged on despite his death. Along the Changjiang, barbarian soldiers wearing red caps and fake beards also rebelled. Ai ordered Sima Yong to send troops against them, but Yong refused. Ai also had a falling out with Sima Ying due to being unable to help him against the rebels.[10] Finally Ai had Li Han arrested and executed which alienated both Yong and Ying.[11]

In 303, Yong sent an army of 70,000 under Zhang Fang to attack the capital. Ying also sent an army 200,000 strong under Lu Ji against the capital. On 21 September 303, Ai sent 10,000 men under Huangfu Shang to oppose Zhang Fang. Zhang Fang caught Huangfu Shang in a surprise attack and defeated him. Meanwhile Ai confronted Lu Ji's vanguard with the main army and defeated it. However he had left Luoyang unguarded, and Zhang Fang took advantage of the situation by taking the capital. On 3 November, Ai personally confronted Lu Ji's army outside Luoyang. Ai's officers had several thousand cavalry equipped with double-ended halberds charge Lu Ji's forces, heavily defeating them. Lu Ji managed to escape but was arrested and executed on Ying's orders. Meng Jiu replaced him as head of military operations.[12]

Ai moved west and defeated Zhang Fang, dealing 5,000 casualties. Zhang Fang returned to Luoyang in the night and built a fortified camp. Ai attacked it unsuccessfully.[13]

Ying offered to split the empire in two with Ai but only if Ai executed Huangfu Shang first. Ai refused.[13]

Zhang Fang severed the Qianjin Dam, effectively cutting off Luoyang's water supply. Ai sent Liu Qin and Huangfu Shang to attack Chang'an. Huangfu Shang was captured and killed however. Despite this Ai held out and by early 304, Zhang Fang had given up hope of taking Luoyang. Seeing this, the Minister of Works, Sima Yue, kidnapped and put Ai under house arrest. Opening the gates, Yue surrendered to the enemy forces. However seeing how few of the opposing army remained, the capital troops regretted surrendering and secretly plotted to free Ai. Fearing the consequences should Ai escape, Yue sent Ai to Zhang Fang, who put Ai to the torch.[14]

Yong recalled Zhang Fang to deal with Liu Qin, who had defeated a subordinate army on his way to Chang'an. On his way back, Zhang Fang seized over 10,000 slave women in Luoyang and cut them into mince meat to feed to his men. They arrived just in time to defeat and capture Liu Qin.[15]

Ying appointed Yue as President of State Secretariat while he himself ruled from Ye. Ying sent an army of 50,000 under Shi Chao to guard Luoyang.[15]

Prince of Chengdu (Sima Ying), 304

On 8 April 304, Sima Ying imprisoned the empress and deposed his nephew, Sima Tan. Ying then appointed himself crown prince. Sima Yue rebelled in Luoyang, restoring the empress and heir to their positions. He amassed an army of over 100,000 at Anyang, south of Ye, and marched on Ying's capital. Ying's general Shi Chao confronted Yue on 9 September 304, and defeated him heavily at the Battle of Dangyin. The emperor was wounded in battle and captured by Shi Chao. Yue fled to Donghai (Shandong). Luoyang fell to the troops of Yong, who decided to assist Ying. Sima Tan and the empress were once again deposed.[16]

In the north, the general Wang Jun, previously under the Jia regime, rebelled. The Southern Xiongnu leader Liu Yuan was brought in by Ying to suppress Wang Jun, but instead he took the opportunity to name himself "King of Han" and made a bid for the imperial throne as a legitimate successor to the Han dynasty.[17] In late Cao Wei or early Jin times, the Southern Xiongnu nobles claimed that they had Han Dynasty ancestry as well—through marriage alliance (Heqin) which many princesses of Han dynasty married many chanyus (ruler of Xiongnu) throughout different period in Xiongnu history and therefore changed their family name to Liu, the same name as the Han imperial clan. Appealing to the Southern Xiongnu, who numbered less than 20,000, Liu Yuan convinced them to join him and reclaim the legacy of their forebearers. Soon his forces swelled to over 50,000.[16]

Lu Zhi urged Ying to use his remaining 15,000 armored troops to escort Emperor Hui of Jin back to Luoyang, but on the morning of their departure, the troops deserted. With no troops left, they fled to Luoyang, where Zhang Fang took possession of Emperor Hui. They were moved to Chang'an and Yong stripped Ying of his position as heir. Sima Chi was conferred the title of crown prince.[18]

Meanwhile in the southwest, Li Xiong created the Ba-Di state of Cheng Han in 304.[19]

Prince of Hejian (Sima Yong), 305

In mid-305, Sima Yue rebelled against Sima Yong and raised an army to take Emperor Hui of Jin back to Luoyang. He was joined by several other princes and the rebel Wang Jun.[20]

Yong freed Sima Ying and Lu Zhi with 1,000 troops to aid rebellions against Yue. On 19 November, he appointed Zhang Fang commander of 100,000 troops and sent him to defend Xuchang. With the aid of Southern Xiongnu and Xianbei cavalry forces, Yue defeated Yong's vanguard force. Yue offered to split the empire in two with Yong. Yong was tempted to take the offer, but Zhang Fang advised him to keep fighting. In response, Yong had Zhang Fang executed and sent his head to Yue as part of a peace offer. Yue ignored it and kept advancing towards Chang'an. By 306, Yue had conquered Chang'an, which his Xianbei auxiliaries plundered, killing 20,000. Yong fled to Mount Taibai, while Ying fled towards Ye (Hebei). Yong later retook Chang'an where he secluded himself. Sima Yue became the latest prince to dominate the imperial court, which he moved back to Luoyang.[21]

Prince of Donghai (Sima Yue), 306–307

Sima Ying fled to Chaoge where he was captured and put under house arrest by Sima Xiao. A month later, however, Sima Xiao died under mysterious circumstances. Xiao's successor Liu Yu forged a false edict ordering the execution of Ying and killed him. Lu Zhi buried Ying and took up a staff position with Sima Yue.

Meanwhile, Sima Yong had taken up arms again and captured Chang'an, but was unable to advance much further than the Guanzhong region. Both sides therefore settled into a stalemate.[21]

Emperor Hui of Jin died on 8 January 307 from eating poisoned wheat cakes. His brother Sima Chi succeeded him, posthumously known as Emperor Huai of Jin. As part of the accession rituals, Emperor Huai issued an edict ordering Yong to come to court as Minister over the Masses. Believing that he was to be pardoned, Yong agreed to attend court. He was killed in an ambush while enroute to the capital by forces loyal to the Prince of Nanyang, Sima Mo.[22]

Conclusion

Sima Yue's victory was short lived. The bandit Wang Mi captured Xuchang in central Henan a year later. At the same time, the former slave of Jie barbarian descent, Shi Le, working under Liu Yuan, sacked Ye. Together Liu Yuan and Shi Le overran most of the lands north of the Yellow River. In 309, Yue sent 3,000 armoured soldiers to kill Emperor Huai of Jin's favored courtiers. This act lost him all the respect of his forces and forced him to further tighten his grip on the court. In April 310, Shi Le captured Xuchang. Emperor Huai plotted with Gou Xi, Yue's second in command, to murder Yue. On 23 April 311, Sima Yue died of stress. Yue's funeral procession was caught by Shi Le on its way to his fief in Shandong. Over 100,000 officers and men were killed, piling atop one another in a mound, not a single one having been able to escape.[23]

Liu Yuan had died in 310 and his son Liu Cong now ruled the Xiongnu state of Han Zhao. With 27,000 Xiongnu troops, Shi Le sacked the Jin capital of Luoyang on 13 July 311 and took Emperor Huai as hostage. This came to be known as the Disaster of Yongjia. The emperor died two years later in captivity and was succeeded by Sima Ye, posthumously Emperor Min of Jin. A vanguard force of 20,000 Xiongnu cavalry rode west and attacked Sima Mo, Yue's sole surviving brother. The main army under two Xiongnu princes broke through the Tong Pass and laid siege to Chang'an, which surrendered in 316. Emperor Min was killed a few months later, thus ending the Western Jin dynasty.[23]

Within four years of his victory in the War of the Eight Princes, Sima Yue had been hounded to death by an assortment of rebellions, invasions, and court politics. Five years after his death, both the capitals of Chang'an and Luoyang had been lost and most of northern China fell under the rule of an assortment of barbarian kingdoms.[23]

See also

- The Eight Princes' family tree

- Sima clan family trees - including some of the Eight Princes

- Murong

- Tuoba

- Xianbei

- Jie people

- Battle of Fei River

References

- Jacques Gernet (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 180. ISBN 0521497817.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 115.

- Institute of Advanced Studies, Australian National University (December 1991). "East Asian History" (PDF). eastasianhistory.org. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- Xiong 2009, p. 414.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 116.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 117.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 118.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 121.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 122.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 124.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 125.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 126.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 127.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 128.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 129.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 130.

- Graff 2001, p. 48.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 131.

- Xiong 2009, p. xci.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 132.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 134.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 135.

- di Cosmo 2009, p. 136.

Bibliography

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2004), Generals of the South

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2004b), Generals of the South 2

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007), A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms, Brill

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2010), Imperial Warlord, Brill

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2017), Fire Over Luoyang: A History of the Later Han Dynasty, 23-220 AD, Brill

- di Cosmo, Nicola (2009), Military Culture in Imperial China, Harvard University Press

- Graff, David A. (2001), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Routledge

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War: Military practice in seventh-century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Lee, Peter H. (1992), Sourcebook of Korean Civilization 1, Columbia University Press

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Lorge, Peter A. (2011), Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-87881-4

- Lorge, Peter (2015), The Reunification of China: Peace through War under the Song Dynasty, Cambridge University Press

- Peers, C.J. (1990), Ancient Chinese Armies: 1500-200BC, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1992), Medieval Chinese Armies: 1260-1520, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1995), Imperial Chinese Armies (1): 200BC-AD589, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1996), Imperial Chinese Armies (2): 590-1260AD, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (2006), Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC - AD 1840, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Peers, Chris (2013), Battles of Ancient China, Pen & Sword Military

- Shin, Michael D. (2014), Korean History in Maps, Cambridge University Press

- Taylor, Jay (1983), The Birth of the Vietnamese, University of California Press

- Taylor, K.W. (2013), A History of the Vietnamese, Cambridge University Press

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0810860538

- Wagner, Donald B. (2008), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5-11: Ferrous Metallurgy, Cambridge University Press