Northern Wei

The Northern Wei or the Northern Wei Empire (/weɪ/),[7] also known as the Tuoba Wei (拓跋魏), Later Wei (後魏), or Yuan Wei (元魏), was a dynasty founded by the Tuoba (Tabgach) clan of the Xianbei, which ruled northern China from 386 to 534 AD[8] (de jure until 535), during the period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties. Described as "part of an era of political turbulence and intense social and cultural change",[9] the Northern Wei Dynasty is particularly noted for unifying northern China in 439: this was also a period of introduced foreign ideas, such as Buddhism, which became firmly established.

Northern Wei 北魏 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 386–535 | |||||||||||||||||||

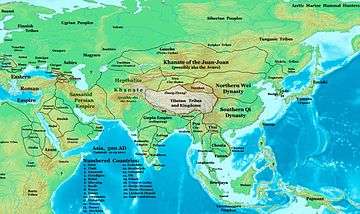

Asia in 500 AD, showing Northern Wei territories and their neighbors | |||||||||||||||||||

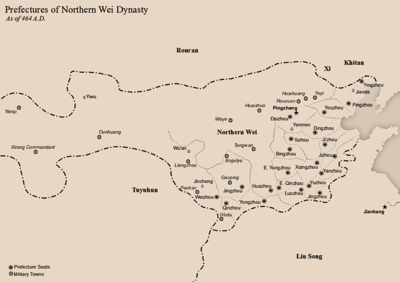

Northern Wei administrative divisions as of 464 AD | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Shengle (386–398, capital of former Dai, near modern Hohhot) Pingcheng (398–493) Luoyang (493–534) Chang'an (534-535) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Tuoba | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||

• 386–409 | Emperor Daowu | ||||||||||||||||||

• 424–452 | Emperor Taiwu | ||||||||||||||||||

• 452-465 | Emperor Wencheng | ||||||||||||||||||

• 471–499 | Emperor Xiaowen | ||||||||||||||||||

• 499–515 | Emperor Xuanwu | ||||||||||||||||||

• 528–530 | Emperor Xiaozhuang | ||||||||||||||||||

• 532–535 | Emperor Xiaowu | ||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 20 February[1] 386 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Emperor Daowu's claim of imperial title | 24 January 399[2] | ||||||||||||||||||

• Unification of northern China | 439 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Movement of capital to Luoyang | 25 October 493[3] | ||||||||||||||||||

• Erzhu Rong's massacre of ruling class | 17 May 528[4] | ||||||||||||||||||

• Establishment of Eastern Wei, marking division | 8 November[5] 535 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Emperor Xiaowu's death | 3 February 535[5] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

| 450[6] | 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Chinese coin, Chinese cash | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | China Mongolia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Northern Wei | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 北魏 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Northern Wei | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | ||||||||

| Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BC | ||||||||

| Xia c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC | ||||||||

| Shang c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC | ||||||||

| Zhou c. 1046 – 256 BC | ||||||||

| Western Zhou | ||||||||

| Eastern Zhou | ||||||||

| Spring and Autumn | ||||||||

| Warring States | ||||||||

| IMPERIAL | ||||||||

| Qin 221–207 BC | ||||||||

| Han 202 BC – 220 AD | ||||||||

| Western Han | ||||||||

| Xin | ||||||||

| Eastern Han | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 | ||||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | ||||||||

| Jin 266–420 | ||||||||

| Western Jin | ||||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | |||||||

| Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | ||||||||

| Sui 581–618 | ||||||||

| Tang 618–907 | ||||||||

| (Wu Zhou 690–705) | ||||||||

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–979 |

Liao 916–1125 | |||||||

| Song 960–1279 | ||||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | |||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | Western Liao | ||||||

| Yuan 1271–1368 | ||||||||

| Ming 1368–1644 | ||||||||

| Qing 1636–1912 | ||||||||

| MODERN | ||||||||

| Republic of China on mainland 1912–1949 | ||||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present | ||||||||

| Republic of China on Taiwan 1949–present | ||||||||

.jpg)

During the Taihe period (477–499) of Emperor Xiaowen, court advisers instituted sweeping reforms and introduced changes that eventually led to the dynasty moving its capital from Datong to Luoyang, in 494. The Tuoba renamed themselves the Han people surname Yuan (元) as a part of systematic Sinicization. Towards the end of the dynasty there was significant internal dissension resulting in a split into Eastern Wei and Western Wei.

Many antiques and art works, both Taoist art and Buddhist art, from this period have survived. It was the time of the construction of the Yungang Grottoes near Datong during the mid-to-late 5th century, and towards the latter part of the dynasty, the Longmen Caves outside the later capital city of Luoyang, in which more than 30,000 Buddhist images from the time of this dynasty have been found.

Rise of the Tuoba Xianbei

The Jin Dynasty had developed an alliance with the Tuoba against the Xiongnu state Han Zhao. In 315 the Tuoba chief was granted the title of the Prince of Dai. After the death of its founding prince, Tuoba Yilu, however, the Dai state stagnated and largely remained a partial ally and a partial tributary state to Later Zhao and Former Yan, finally falling to Former Qin in 376.

After Former Qin's emperor Fu Jiān was defeated by Jin forces at the Battle of Fei River in his failed bid to unify China, the Former Qin state began to break apart. By 386, Tuoba Gui, the son (or grandson) of Tuoba Shiyijian (the last Prince of Dai), reasserted Tuoba independence initially as the Prince of Dai. Later he changed his title to the Prince of Wei, and his state was therefore known as Northern Wei. In 391, Tuoba Gui defeated the Rouran tribes and killed their chief, Heduohan, forcing the Rouran to flee west.

Initially Northern Wei was a vassal of Later Yan, but by 395 had rebelled and defeated the Yan at the Battle of Canhebei. By 398 the Wei had conquered most of Later Yan territory north of the Yellow River. In 399, Tuoba Gui declared himself Emperor Daowu, and that title was used by Northern Wei's rulers for the rest of the empire's history. That same year he defeated the Tiele tribes near the Gobi desert.

Unification of Northern China

In 426, Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei settled on making the Xiongnu-ruled Kingdom of Xia his target. He then sent his generals to attack Puban (modern Yuncheng) and Shancheng (modern Sanmenxia), while himself siege the Xia's heavily fortified capital of Tongwancheng. Tongwancheng fell in 427, forcing the Xia emperor Helian Chang to flee westward. He was captured nevertheless in 428 and his brother, Helian Ding, took over as the emperor of Xia.

In fall 430, while Helian Ding was engaging the Western Qin, the Northern Wei made a surprise attack on the new Xia capital Pingliang and conquered the kingdom.

In summer 432, Emperor Taiwu, with Xia destroyed, began to attack Northern Yan and its capital Helong (和龍, in modern Jinzhou, Liaoning) under siege. He chose to withdraw at the start of winter and would launch yearly attacks against Northern Yan to weaken it gradually over the next few years. In 436 the Yan emperor Feng Hong had to evacuate his state and fled to Goguryeo, ending Northern Yan.

In 439, the Northern Wei launched a major attack on Northern Liang, capturing its capital Guzang (modern Wuwei, Gansu) . By 441, entire Northern Liang territory was under the Wei. Northern China was now united under Emperor Taiwu's reign, ending the Sixteen Kingdoms era and starting the Southern and Northern Dynasties era.

Wars with the Southern dynasties

War with Liu Song

War between Northern Wei and Han-ruled Liu Song dynasty broke out while the former had not yet unified northern China. Emperor Wu of Liu Song while still a Jin dynasty general, had conquered both Southern Yan in 410 and Later Qin in 417, pushing Jin frontiers further north into Wei territories. He then usurped the Jin throne and created the Song dynasty. After hearing the death of the Song emperor Wu in 422, Wei's emperor Mingyuan broke off relations with Song and sent troops to invade its southern neighbor. His plan is to seize three major cities south of the Yellow River: Luoyang, Hulao, and Huatai. Sizhou (司州, central Henan) and Yanzhou (兗州, modern western Shandong) and most cities in Song's Qing Province (青州, modern central and eastern Shandong) fell to the Wei army. The Liu Song general Tan Daoji commanded an army to try to save those cities and were able to hold Dongyang (東陽, in modern Qingzhou, Shandong),the capital of Qingzhou province. Northern Wei troops were eventually forced to withdraw after food supplies ran out. Wei forces also stalled in their siege of Hulao, defended by the capable Liu Song general Mao Dezu (毛德祖), but were meanwhile able to capture Luoyang and Xuchang (許昌, in modern Xuchang, Henan) in spring 423, cutting off the path of any Liu Song relief force for Hulao. In summer 423, Hulao fell. The campaign then ceased, with Northern Wei now in control of much of modern Henan and western Shandong.

Emperor Wen of Liu Song continued the northern campaigns of his father. In 430, under the able general Dao Yanzhi, Liu Song recovered the four cities of Luoyang, Hulao, Huatai and Qiao'ao south of the Yellow River. However, the emperor's unwillingness to advance past this line caused the destruction of the empire's ally, Xia, by the Wei. The emperor was to repeat this mistake as several northern states such as Northern Yan who had offered to ally with Liu Song against Wei were declined, eventually leading to Wei's unification of the North in 439.

In 450, Emperor Wen attempted to destroy the Northern Wei by himself and launched a massive invasion. Although initially successful, the campaign turned into a disaster. The Wei lured the Liu Song to cross the Yellow River, and then flanked them, destroying the Eastern army.

As the Liu Song armies retreated, Emperor Taiwu of Wei ordered his troop to move south. The provinces south of the Yellow River were devastated by the Wei army. Only Huatai, a fortified city, held out against the Wei. Wei troops retreated in January 451, however, the economic damage to the Song was immense. Emperor Wen made another attempt to conquer Northern Wei in 452, but failed again. On returning to the capital, he was assassinated by the heir apparent, Liu Shao.

In 466, Liu Zixun waged an unsuccessful civil war against the Emperor Ming of Liu Song. The governors of Xu Province (徐州) and Yan Province (兗州, modern western Shandong), who earlier pleaded allegiance to Liu Zixun, in fear of reprisal from the Liu Song Emperor, surrendered these territories to rival Northern Wei. Northern Wei forces quickly took up defense position against the attacking forces sent by Emperor Ming. With Liu Song forces unable to siege Pengcheng effectively, they were forced to withdraw in spring 467, making these populous provinces lost to the Northern Wei.

War with Southern Qi

In 479, Xiao Daocheng usurped the throne of Liu Song and became emperor of the new Southern Qi dynasty. Upon hearing the news, the Northern Wei emperor prepared to invade under the pretext of installing Liu Chang, son of Emperor Wen of Liu Song who had been in exile in Wei since 465 AD.

Wei troops began to attack Shouyang but could not take the city. The Southern Qi began to fortified their capital, Jiankang in order to prevent further Wei raids.

Multiple sieges and skirmishes were fought until 481 but the war was without any major campaign. A peace treaty was signed in 490 with the Emperor Wu.

War with Liang

In 502, the Southern Qi general Xiao Yan toppled the Emperor Xiao Baojuan after waging a three years civil war against him. Xiao Yan enthroned in Jiankang to become the Emperor Wu of Liang dynasty.

As soon as 503 AD, the Northern Wei was hoping to restore the Southern Qi throne. Their plan was install Xiao Baoyin, a Southern Qi prince to become Emperor of the puppet state. A southern expedition was led by Prince Yuan Cheng of Wei and Chen Bozhi, a former Qi general. Until spring 505, Xinyang and Hanzhong were fallen to the Northern Wei.

In 505, Emperor Wu began the Liang offensive. A strong army was quickly amassed under the general Wei Rui and caught the Wei by surprise, calling it the strongest army they have seen from the Southern Dynasties in a hundred years. In spring 506, Wei Rui was able to capture Hefei. In fall 506, Wei Rui attacked the Northern Wei army stationed at Luokou for nearly a year without advancing. However, when Wei army gathered, Xiao Hong Prince of Linchuan, the Liang commander and younger brother of Emperor Wu, escaped in fear, causing his army to collapse without a battle. Northern Wei forces next attacked the fortress of Zhongli (鍾離, in modern Bengbu), However, they were defeated by a Liang army commanded by Wei Rui and Cao Jingzong, effectively ending the war. After the Battle of Zhongli, there would continue to be border battles from time to time, but no large scale war for years.

In 524, while Northern Wei is plagued by agrarian rebellions to the north and west, Emperor Wu launched a number of attacks on Wei's southern territory. Liang forces largely met little resistance. In spring 525, the Northern Wei general Yuan Faseng (元法僧) surrendered the key city of Pengcheng (彭城, in modern Xuzhou, Jiangsu) to Liang. However, in summer 525, Emperor Wu's son Prince Xiao Zong (蕭綜), grew suspicions that he was actually the son of Southern Qi's emperor Xiao Baojuan (because his mother Consort Wu was formerly Xiao Baojuan's concubine and had given birth to him only seven months after she became Emperor Wu's concubine), surrendered Pengcheng to Northern Wei, ending Liang's advances in the northeast, although in summer 526, Shouyang fell to Liang troops after Emperor Wu successfully reemployed the damming strategy. For the next several years, Liang continued to make minor gains on the borders with Northern Wei.

In 528, after a coup in Northern Wei, with the warlord Erzhu Rong overthrowing Empress Dowager Hu, a number of Northern Wei officials, including Yuan Yue, Yuan Yu, and Yuan Hao fled and surrendered territories they controlled to Liang. In winter 528, Emperor Wu created Yuan Hao the Prince of Wei—intending to have him lay claim to the Northern Wei throne and, if successful, become a Liang vassal. He commissioned his general Chen Qingzhi (陳慶之) with an army to escort Yuan Hao back to Northern Wei. Despite the small size of Chen's army, he won battle after battle, and in spring 529, after Chen captured Suiyang (modern Shangqiu). Yuan Hao, with Emperor Wu's approve, proclaimed himself the emperor of Northern Wei. In summer 529, troops under Erzhu unable to stand up to Chen Qingzhi, forcing Emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei to flee the capital Luoyang. After capturing Luoyang, Yuan Hao secretly wanted to rebel against Liang: when Chen Qingzhi requested Emperor Wu to send reinforcements, Yuan Hao sent Emperor Wu a submission advising against it, and Emperor Wu, believing Yuan Hao, did not send additional troops. Soon, Erzhu and Emperor Xiaozhuang counterattacked, and Luoyang fell. Yuan Hao fled and was killed in flight, and Chen's own army was destroyed, although Chen himself was able to flee back to Liang.

In 530, Emperor Wu made another attempt to establish a vassal regime in Northern Wei by creating Yuan Yue the Prince of Wei, and commissioning Yuan Yue's uncle Fan Zun (范遵) with an army to escort Yuan Yue back to Northern Wei. Yuan Yue made some advances, particularly in light of the disturbance precipitated soon thereafter when Emperor Xiaozhuang ambushed and killed Erzhu Rong and was in turn overthrown by Erzhu Rong's nephew Erzhu Zhao and cousin Erzhu Shilong. However, Yuan Yue realized that the Erzhus then became firmly in control of Luoyang and that he would be unable to defeat them, and so returned to Liang in winter 530.

In 532, with Northern Wei again in civil war after the general Gao Huan rose against the Erzhus, Emperor Wu against sent an army to escort Yuan Yue back to Northern Wei, and subsequently, Gao Huan welcomed Yuan Yue, but then decided against making Yuan Yue emperor. Subsequently, Emperor Xiaowu of Northern Wei, whom Gao made emperor, had Yuan Yue executed.

With Northern Wei divided into Eastern Wei and Western Wei in light of Emperor Xiaowu's flight, Emperor Wu initially continued to send his forces to make minor territorial gains on the borders, against both Eastern Wei and Western Wei, for several years.

Policies

Early in Northern Wei history, the state inherited a number of traditions from its initial history as a Xianbei tribe, and some of the more unusual ones, from a traditional Chinese standpoint:

- The officials did not receive salaries, but were expected to requisition the necessities of their lives directly from the people they governed. As Northern Wei Empire's history progressed, this appeared to be a major contributing factor leading to corruption among officials. Not until the 2nd century of the empire's existence did the state begin to distribute salaries to its officials.

- Empresses were not named according to imperial favors or nobility of birth, but required that the candidates submit themselves to a ceremony where they had to personally forge golden statues, as a way of discerning divine favor. Only an imperial consort who was successful in forging a golden statue could become the empress.

- All men, regardless of ethnicity, were ordered to tie their hair into a single braid that would then be rolled and placed on top of the head, and then have a cap worn over the head.

- When a crown prince is named, his mother, if still alive, must be forced to commit suicide. (Some historians do not believe this to be a Tuoba traditional custom, but believed it to be a tradition instituted by the founding emperor Emperor Daowu based on Emperor Wu of Han's execution of his favorite concubine Consort Zhao, the mother of his youngest son Liu Fuling (the eventual Emperor Zhao), before naming Prince Fuling crown prince.)

- As a result, because emperors would not have mothers, they often honored their wet nurses with the honorific title, "Nurse Empress Dowager" (保太后, bǎo tài hòu).

As Sinicization of the Northern Wei state progressed, these customs and traditions were gradually abandoned.

Administrative organization

- Five families formed a neighborhood (lin)[10]

- Five lin formed a village (li)

- Five li formed a commune (tang)

At each of these levels, leaders that were associated with the central government were appointed. In order for the state to reclaim dry, barren areas of land, the state further developed this system by dividing up the land according to the number of men of an age to cultivate it. The Sui and Tang Dynasties later resurrected this system in the 7th century.[10]

Deportations

During the reign of Emperor Daowu (386-409), the total number of deported people from the regions east of Taihangshan (the former Later Yan territory) to Datong was estimated to be around 460,000. Deportations typically took place once a new piece of territory had been conquered.[10]

| Northern Wei Dynasty Deportations | |||

| Year | People | Number | Destination |

|---|---|---|---|

| 398 | Xianbei of Hebei and Northern Shandong | 100,000 | Datong |

| 399 | Great Chinese families | 2,000 families | Datong |

| 399 | Chinese peasants from Henan | 100,000 | Shanxi |

| 418 | Xianbei of Hebei | ? | Datong |

| 427 | Pop. of the Kingdom of Xia | 10,000 | Shanxi |

| 432 | Pop. of Liaoning | 30,000 families | Hebei |

| 435 | Pop. of Shaanxi and Gansu | ? | Datong |

| 445 | Chinese peasants from Henan and Shandong | ? | North of Yellow River |

| 449 | Craftsmen from Chang'an | 2,000 families | Datong |

Sinicization

As the Northern Wei state grew, the emperors' desire for Han Chinese institutions and advisors grew. Cui Hao (381-450), an advisor at the courts in Datong played a great part in this process.[10] He introduced Han Chinese administrative methods and penal codes in the Northern Wei state, as well as creating a Taoist theocracy that lasted until 450. The attraction of Han Chinese products, the royal court's taste for luxury, the prestige of Chinese culture at the time, and Taoism were all factors in the growing Chinese influence in the Northern Wei state. Chinese influence accelerated during the capital's move to Luoyang in 494 and Emperor Xiaowen continued this by establishing a policy of systematic sinicization that was continued by his successors. Xianbei traditions were largely abandoned. The royal family took the sinicization a step further by changing their family name to Yuan. Marriages to Chinese families were encouraged. With this, Buddhist temples started appearing everywhere, displacing Taoism as the state religion. The temples were often created to appear extremely lavish and extravagant on the outside of the temples.[10] Also from 460 onwards the emperors started erecting huge statues of the Buddha carved near their capital Pingcheng which declared the emperors as the representatives of the Buddha and the legitimate rulers of China.[11]

The Northern Wei started to arrange for Han Chinese elites to marry daughters of the Xianbei Tuoba royal family in the 480s.[12] More than fifty percent of Tuoba Xianbei princesses of the Northern Wei were married to southern Han Chinese men from the imperial families and aristocrats from southern China of the Southern dynasties who defected and moved north to join the Northern Wei.[13] Some Han Chinese exiled royalty fled from southern China and defected to the Xianbei. Several daughters of the Xianbei Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei were married to Han Chinese elites, the Liu Song royal Liu Hui 劉輝), married Princess Lanling (蘭陵公主) of the Northern Wei,[14][15][16][17][18][19] Princess Huayang (華陽公主) to Sima Fei (司馬朏), a descendant of Jin dynasty (265–420) royalty, Emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei's sister the Shouyang Princess was wedded to the Liang dynasty ruler Emperor Wu of Liang's son Xiao Zong 蕭綜.[20]

When the Eastern Jin dynasty ended Northern Wei received the Han Chinese Jin prince Sima Chuzhi (司馬楚之) as a refugee. A Northern Wei Princess married Sima Chuzhi, giving birth to Sima Jinlong (司馬金龍). Northern Liang Xiongnu King Juqu Mujian's daughter married Sima Jinlong.[21]

The Northern Wei's Eight Noble Xianbei surnames (八大贵族) were the Buliugu (步六孤), Helai (賀賴), Dugu (獨孤), Helou (賀樓), Huniu (忽忸), Qiumu (丘穆), Gexi (紇奚), and Yuchi (尉遲). They adopted Chinese last names.

Kongzi was honoured in sacrifices as was Earth and Heaven by the northern dynasties of non-Han origin.[22] Kongzi was honored by the Murong Wei Former Yan Xianbei leader.[23] Kongzi was honored by the Di ruler Fu Jian (337–385).[24] Kongzi was honored in sacrifices by the Northern Wei Xianbei dynasty. Kongzi was honored by Yuoba Si, the Mingyuan emperor.[25] Han dynasty Emperors, Shang dynasty ruler Bigan, Emperor Yao and Emperor Shun were honored by Yuoba Si, the Mingyuan Emperor. Kongzi was honored extensively by Tuoba Hong, the Xiaowen Emperor.[26]

A fief of 100 households and the rank of (崇聖侯) Marquis who worships the sage was bestowed upon a Confucius descendant, Yan Hui's lineage had 2 of its scions and Confucius's lineage had 4 of its scions who had ranks bestowed on them in Shandong in 495 and a fief of ten households and rank of (崇聖大夫) Grandee who venerates the sage was bestowed on Kong Sheng (孔乘) who was Confucius's scion in the 28th generation in 472 by Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei.[27][28]

An anti Buddhist plan was concocted by the Celestial Masters under Kou Qianzhi along with Cui Hao under the Taiwu Emperor.[29] The Celestial Masters of the north urged the persecution of Buddhists under the Taiwu Emperor in the Northern Wei, attacking Buddhism and the Buddha as wicked and as anti-stability and anti-family.[30] Anti Buddhism was the position of Kou Qianzhi.[31] There was no ban on the Celestial Masters despite the nonfullfilment of Cui Hao and Kou Qianzhi's agenda in their anti-Buddhist campaign.[32]

Cui Zhen's wife Han Farong was buried in a Datong located grave.[33]

Building the Great Wall

To resist the threats poised by the Rourans, Northern Wei emperors started to embark on building its own Great Wall, the first since the Han dynasty. In 423, a defence line over 2,000 li (1,080 kilometres (670 mi)) long was built ; its path roughly followed the old Zhao wall from Chicheng County in Hebei Province to Wuyuan County, Inner Mongolia.[34] In 446, 100,000 men were put to work building an inner wall from Yanqing, passing south of the Wei capital Pingcheng, and ending up near Pingguan on the eastern bank of the Yellow River. The two walls of Northern Wei formed the basis of the double-layered Xuanfu–Datong wall system that protected Beijing a thousand years later during the Ming dynasty.

Disunity and breakup

.jpg)

The heavy Chinese influence that had come into the Northern Wei state which went on throughout the 5th century had mainly affected the courts and the upper ranks of the Tuoba aristocracy.[10] Armies that guarded the Northern frontiers of the empire and the Xianbei people who were less sinicized began showing feelings of hostility towards the aristocratic court and the upper ranks of civil society.[10] Early in Northern Wei history, defense on the northern border against Rouran was heavily emphasized, and military duty on the northern border was considered honored service that was given high recognition. After all, throughout the founding and the early stages of the Northern Wei, it was the strength of the sword and bow that carved out the empire and kept it. But once Emperor Xiaowen's sinicization campaign began in earnest, military service, particularly on the northern border, was no longer considered an honorable status, and traditional Xianbei warrior families on the northern border were disrespected and disallowed many of their previous privileges; these warrior families who had originally been held as the upper-class now found themselves considered a lower-class on the social hierarchy.

Six Frontier Towns rebellions

Rebellions broke out on six major garrison-towns on the northern border and spread like wildfire throughout the north. These rebellions lasted for a decade.

In 523, nomadic Rouran tribes suffered a major famine due to successive years of drought. In April, the Rouran Khan sent troops to plunder Huaihuang to solve the famine. People of the town rose up and killed the town's commander. Rebellion soon broke out against the Luoyang court across the region. In Woye, Poliuhan Baling (破六韓拔陵) became a rebel leader. His army quickly took Woye and laid siege to Wuchuan and Huaishuo.

Elsewhere in Qinzhou (Gansu), Qiang ethnic leaders such as Mozhe Dati (莫折大提) also rose up against the government. In Gaoping (present-day Guyuan), Hu Chen (胡琛) and the Xiongnu rebelled and titled himself the King of Gaoping. In Hebei, Ge Rong rebelled, proclaiming himself the Emperor of Qi.

The Poliuhan Baling rebellion was defeated in 525. However, other anti-Sinicization rebellions had spread to other regions such as Hebei and Guanzhong and only be pacified as late as 530.

Rise of Erzhu Rong and Heyin Massacre

Exacerbating the situation, Empress Dowager Hu poisoned her own son Emperor Xiaoming in 528 after Emperor Xiaoming showed disapproval of her handling of the affairs as he started coming of age and got ready to reclaim the power that had been held by the empress in his name when he inherited the throne as an infant, giving the Empress Dowager rule of the country for more than a decade. Upon hearing the news of the 18-year-old emperor's death, the general Erzhu Rong, who had already mobilised on secret orders of the emperor to support him in his struggle with the Empress Dowager Hu, turned toward Luoyang. Announcing that he was installing a new emperor chosen by an ancient Xianbei method of casting bronze figures, Erzhu Rong summoned the officials of the city to meet their new emperor. However, on their arrival, he told them they were to be punished for their misgovernment and butchered them, throwing the Empress Hu and her candidate (another puppet child emperor Yuan Zhao) into the Yellow River. Reports estimate 2,000 courtiers were killed in this Heyin massacre on the 13th day of the second month of 528.[lower-alpha 1] Erzhu Rong claimed Yuan Ziyou grandson of Emperor Xianwen the new emperor as Emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei.

In 529, Liang general Chen Qingzhi sacked Luoyang, forced Emperor Xiaozhuang to flee and claimed Yuan Hao another grandson of Emperor Xianwen emperor, before his final defeat by Erzhu Rong.

Civil war and the two generals

The Erzhu clan dominated the imperial court thereafter, the emperor held power in name only and most decisions actually went through the Erzhus. The emperor did stop most of the rebellions, largely reunifying the Northern Wei state. However, Emperor Xiaozhuang, not wishing to remain a puppet emperor and highly wary of the Erzhu clan's widespread power and questionable loyalty and intentions towards the throne (after all, this man had ordered a massacre of the court and put to death a previous emperor and empress before), killed Erzhu Rong in 530 in an ambush at the palace, which led to a resumption of civil war, initially between Erzhu's clan and Emperor Xiaozhuang, and then, after their victory over Emperor Xiaozhuang in 531, between the Erzhu clan and those who resisted their rule. In the aftermath of these wars, two generals set in motion the actions that would result in the splitting of the Northern Wei into the Eastern and Western Wei.

General Gao Huan was originally from the northern frontier, one of many soldiers who had surrendered to Erzhu, who eventually became one of the Erzhu clan's top lieutenants. But later, Gao Huan gathered his own men from both Han and non-Han troops, to turn against the Erzhu clan, entering and taking the capital Luoyang in 532. Confident in his success, he deposed Emperor Jiemin of Northern Wei the emperor claimed by Erzhu's clan and Yuan Lang the emperor claimed by Gao himself for too distant, set up a nominee emperor Emperor Xiaowu of Northern Wei on the Luoyang throne and continued his campaigns abroad. The emperor, however, together with the military head of Luoyang, Husi Chun, began to plot against Gao Huan. Gao Huan succeeded, however, in keeping control of Luoyang, and the unfaithful ruler and a handful of followers fled west, to the region ruled by the powerful warlord Yuwen Tai. Gao Huan then announced his decision to move the Luoyang court to his capital city of Ye. "Within three days of the decree, 400,000 families--perhaps 2,000,000 people--had to leave their homes in and around the capital to move to Yeh as autumn turned to winter."[36] There now existed two rival claimants to the Northern Wei throne, leading to the state's division in 534-535 into the Eastern Wei and Western Wei.

Fall

Neither Eastern Wei nor Western Wei was long-lived.[37] In 550, Gao Huan's son Gao Yang forced Emperor Xiaojing of Eastern Wei to yield the throne to him, ending Eastern Wei and establishing the Northern Qi. Similarly, in 557, Yuwen Tai's nephew Yuwen Hu forced Emperor Gong of Western Wei to yield the throne to Yuwen Tai's son Yuwen Jue, ending the Western Wei and establishing the Northern Zhou. In 581, the Northern Zhou official Yang Jian had the emperor to yield the throne to him, establishing Sui Dynasty, finally extinguishing imperial rule of the Xianbei.

Culture and legacy

The Northern Wei dynasty was the most long-lived and most powerful of the northern dynasties prior to the reunification of China by the Sui dynasty. Northern Wei art came under influence of Indian and Central Asia traditions through the mean of trade routes. Most importantly for Chinese art history, the Wei rulers converted to Buddhism and became great patrons of Buddhist arts.

Many of the most important heritages of China, such as the Yungang Grottoes, the Longmen Caves, the Shaolin Monastery, the Songyue Pagoda, were built by the Northern Wei. Important books such as Qimin Yaoshu and Commentary on the Water Classic, a monumental work on China's geography, was written during the era.

The Legend of Hua Mulan is originated from the Northern Wei era, in which Mulan disguised as a man, takes her aged father's place in the Wei army to defend China from Rouran invaders.

Sovereigns of the Northern Wei Dynasty

| Posthumous Name | Personal Name | Period of Reign | Era Names |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daowu | Tuoba Gui | 386-409 | Dengguo (登國) 386-396 Huangshi (皇始) 396-398 Tianxing (天興) 398-404 Tianci (天賜) 404-409 |

| Mingyuan | Tuoba Si | 409-423 | Yongxing (永興) 409-413 Shenrui (神瑞) 414-416 Taichang (泰常) 416-423 |

| Taiwu | Tuoba Tao | 424-452 | Shiguang (始光) 424-428 Shenjia (神䴥) 428-431 Yanhe (延和) 432-434 Taiyan (太延) 435-440 Taipingzhenjun (太平真君) 440-451 Zhengping (正平) 451-452 |

| – | Tuoba Yu | 452 | Chengping (承平) 452 |

| Wencheng | Tuoba Jun | 452-465 | Xingan (興安) 452-454 Xingguang (興光) 454-455 Tai'an (太安) 455-459 Heping (和平) 460-465 |

| Xianwen | Tuoba Hong | 466-471 | Tian'an (天安) 466-467 Huangxing (皇興) 467-471 |

| Xiaowen | Tuoba Hong Yuan Hong[lower-alpha 2] |

471-499 | Yanxing (延興) 471-476 Chengming (承明) 476 Taihe (太和) 477-499 |

| Xuanwu | Yuan Ke | 499-515 | Jingming (景明) 500-503 Zhengshi (正始) 504-508 Yongping (永平) 508-512 Yanchang (延昌) 512-515 |

| Xiaoming | Yuan Xu | 516-528 | Xiping (熙平) 516-518 Shengui (神龜) 518-520 Zhengguang (正光) 520-525 Xiaochang (孝昌) 525-527 Wutai (武泰) 528 |

| – | Yuan Zhao[lower-alpha 3] | 528 | – |

| Xiaozhuang | Yuan Ziyou | 528-530[lower-alpha 4] | Jianyi (建義) 528 Yongan (永安) 528-530 |

| – | Yuan Ye | 530-531 | Jianming (建明) 530-531 |

| Jiemin | Yuan Gong | 531-532 | Putai (普泰) 531-532 |

| – | Yuan Lang | 531-532 | Zhongxing (中興) 531-532 |

| Xiaowu | Yuan Xiu | 532-535 | Taichang (太昌) 532 Yongxing (永興) 532 Yongxi (永熙) 532-535 |

- Gallery

A Buddhist stela from the Northern Wei period, build in the early 6th century.

A Buddhist stela from the Northern Wei period, build in the early 6th century. Mounted warrior of the Northern Wei Dynasty from the collections of the Musée Cernuschi.

Mounted warrior of the Northern Wei Dynasty from the collections of the Musée Cernuschi.- Figurines of court ladies, Royal Ontario Museum.

Male figure wearing Hanfu robes, from a lacquerware painting over wood, Northern Wei period, 5th century AD

Male figure wearing Hanfu robes, from a lacquerware painting over wood, Northern Wei period, 5th century AD Northern Wei wall murals and painted figurines, Yungang Grottoes, 5th to 6th centuries.

Northern Wei wall murals and painted figurines, Yungang Grottoes, 5th to 6th centuries.

Notes

- 1,300 or 2000 according to different versions of the Book of Wei[35]

- The imperial Tuoba family changed their family name to Yuan (元) during the reign of Emperor Xiaowen in 496 so their names in this table will also thus be "Yuan" subsequently.

- Empress Dowager Hu initially declared Emperor Xiaoming's "son" (actually a daughter) emperor, but almost immediately after admitted that she was actually female and declared Yuan Zhao emperor instead. Emperor Xiaoming's unnamed daughter was therefore arguably an "emperor" and his successor, but is not commonly regarded as one. Indeed, Yuan Zhao himself is often not considered an emperor.

- The Northern Wei imperial prince Yuan Hao, under support by rival Liang Dynasty's troops, declared himself emperor and captured the capital Luoyang in 529, forcing Emperor Xiaozhuang to flee. Yuan Hao carried imperial title and received pledges of allegiance from provinces south of the Yellow River for about three months before Erzhu Rong recaptured Luoyang. Yuan Hao fled and was killed in flight. Due to the briefness of Yuan Hao's claim on the throne and the limited geographic scope of his reign, he is usually not counted among the succession of Northern Wei emperors.

References

Citations

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 106.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 110.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 138.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 152.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 156.

- Rein Taagepera "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.", Social Science History Vol. 3, 115-138 (1979)

- "Wei". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 60–65. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- Katherine R. Tsiang, p. 222

-

- Jacques Gernet (1972). "A History Of Chinese Civilization". Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24130-8

- Liu, Xinru (2010). The Silkroad in World History. Oxford University Press. p. 77.

- Rubie Sharon Watson (1991). Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. University of California Press. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-520-07124-7.

- Tang, Qiaomei (May 2016). Divorce and the Divorced Woman in Early Medieval China (First through Sixth Century) (PDF) (A dissertation presented by Qiaomei Tang to The Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of East Asian Languages and Civilizations). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. pp. 151, 152, 153.

- Lee (2014).

- Papers on Far Eastern History. Australian National University, Department of Far Eastern History. 1983. p. 86.

- Hinsch, Bret (2018). Women in Early Medieval China. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 97. ISBN 978-1538117972.

- Hinsch, Bret (2016). Women in Imperial China. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 72. ISBN 978-1442271661.

- Lee, Jen-der (2014). "9. Crime and Punishment The Case of Liu Hui in the Wei Shu". In Swartz, Wendy; Campany, Robert Ford; Lu, Yang; Choo, Jessey (eds.). Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 156–165. ISBN 978-0231531009.

- Australian National University. Dept. of Far Eastern History (1983). Papers on Far Eastern History, Volumes 27-30. Australian National University, Department of Far Eastern History. pp. 86, 87, 88.

- Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature (vol.3 & 4): A Reference Guide, Part Three & Four. BRILL. 22 September 2014. pp. 1566–. ISBN 978-90-04-27185-2.

- China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

sima.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (23 November 2009). Early Chinese Religion, Part Two: The Period of Division (220-589 AD) (2 vols). BRILL. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-90-474-2929-6.John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220-589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (23 November 2009). Early Chinese Religion, Part Two: The Period of Division (220-589 AD) (2 vols). BRILL. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-90-474-2929-6.John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220-589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (23 November 2009). Early Chinese Religion, Part Two: The Period of Division (220-589 AD) (2 vols). BRILL. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-90-474-2929-6.John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220-589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (23 November 2009). Early Chinese Religion, Part Two: The Period of Division (220-589 AD) (2 vols). BRILL. pp. 140–. ISBN 978-90-474-2929-6.John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220-589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 140–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (23 November 2009). Early Chinese Religion, Part Two: The Period of Division (220-589 AD) (2 vols). BRILL. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-90-474-2929-6.John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220-589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220-589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 257–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (23 November 2009). Early Chinese Religion, Part Two: The Period of Division (220-589 AD) (2 vols). BRILL. pp. 257–. ISBN 978-90-474-2929-6.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220-589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 533–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220-589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 534–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220-589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 535–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220-589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 539–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- http://www.livescience.com/55790-ancient-bling-found-in-chinese-tomb.html http://i.imgur.com/h9ROrBf.jpg http://www.archaeology.org/news/4767-160817-china-northern-wei-dynasty-tomb

- Lovell, Julia (2006). The Great Wall : China against the world 1000 BC – 2000 AD. Sydney: Picador Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-42241-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenner, W.J.F. (1981), Memories of Loyang: Yang Hsuan-chih and the Lost Capital (493-534), Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 90.

- Jenner, Memories of Loyang, p. 101.

- Charles Holcombe, A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century, p 68 Cambridge University Press, 2011

Sources

- Book of Wei.

- Jenner, W. J. F. Memories of Loyang: Yang Hsuan-chih and the lost capital (493-534). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981.

- History of Northern Dynasties.

- Lee Jen-der (2014), "Crime and Punishment: The Case of Liu Hui in the Wei Shu", Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 156–165, ISBN 978-0-231-15987-6.

- Tsiang, Katherine R. "Changing Patterns of Divinity and Reform in the Late Northern Wei" in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 84 No. 2 (June 2002), pp. 222–245.

- Zizhi Tongjian.

External links